- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

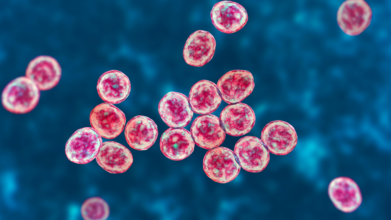

Dozens Sickened, Four Dead In New York City Legionnaires’ Outbreak: Are NYC’s Cooling Towers Really The Problem?

Credits: Canva

As of August 14, 2025, health officials confirmed that the fourth person has died during an outbreak of Legionnaires' disease in Central Harlem, a somber landmark in a crisis that has afflicted dozens of people in recent weeks. At least 17 individuals have been hospitalized, and the source has been traced by investigators to dirty cooling towers on several buildings, including facilities owned by the city itself.

The epidemic, which was first reported in late July, has attracted national concern not just due to its impact but also due to the fact that it demonstrates how contemporary urban infrastructure can serve as a hotbed for public health crises.

The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene said Legionella bacteria were found in 12 cooling towers on 10 buildings in Central Harlem. They included a city-owned hospital and a sexual health clinic. Although remediation work—chemical cleanings and disinfections—has been done in 11 towers, work is ongoing at one location, with completion by Friday anticipated.

Acting city health commissioner Dr. Michelle Morse stated that cases in the outbreak have started to decrease, an indication that the interventions are effective. Nevertheless, she advised residents and employees in the neighborhood to be cautious. "If you work or live in the area and have flu-like symptoms, don't dismiss them. Get medical care right away," Morse reiterated.

Legionnaires' disease is not new, but outbreaks can be fatal when detection and treatment are slow. It is a serious type of pneumonia produced by Legionella bacteria, which multiply in warm, moving water. People become infected after breathing in tiny water droplets that contain the bacteria. Typical sources include:

- Air-conditioning cooling towers in big buildings

- Hot tubs or spas

- Decorative water fountains or water features

- Shower heads and stagnant warm water plumbing systems

Unlike COVID-19 or the flu, Legionnaires' disease is not transmitted between people. Exposure is solely through environmental sources. Two to 14 days after exposure, symptoms typically manifest and consist of cough, fever, chills, headache, muscle pains, and shortness of breath. More severe forms may result in respiratory failure or death if not addressed in time.

Why Cooling Towers Are at the Center of This Outbreak?

Cooling towers are tall, open-air buildings utilized in HVAC systems to control building temperatures. They operate by evaporating water into the air, which is a possible highway for the spread of Legionella bacteria if the system is not kept well maintained.

During the Harlem outbreak, cases were traced to positive test results from cooling towers, including some in city-owned facilities. Though cleanup has been rapid, the fact that contaminated systems were present in public facilities called into question maintenance monitoring and whether preventive inspections were adequate.

The city has emphasized that Harlem's tap water is still safe. The residents can drink, cook, bathe, and run their home air conditioners without fear, as the outbreak is not related to the municipal water supply but building cooling towers.

While anyone technically can contract Legionnaires' disease after exposure, the CDC recognizes the following groups of people as being especially susceptible:

- Adults over the age of 50

- Individuals with chronic lung disease, diabetes, kidney or liver failure

- People with compromised immune systems from cancer or immunosuppressive treatment

- Former and active smokers

For these populations, infection can rapidly become life-threatening. In Harlem, officials did not provide personal information on the four who have died, but in the past, death has been more likely in patients with underlying disease.

Although this outbreak has grabbed headlines, Legionnaires' disease is not unusual in America. Nationwide, an estimated 6,000 cases are reported annually, although experts suspect the true number is probably higher because underdiagnosis or mistaken identification with other forms of pneumonia tends to happen.

In New York State alone, 200 to 800 cases are reported each year. Outbreaks occur more frequently during the summer months, when air-conditioning systems of buildings are operating at their peak. This seasonal pattern is reflected in the clustering of Harlem cases.

Legionnaires' disease can be treated with antibiotics, but timing is everything. Complications are much less likely when treatment is initiated early. Delayed diagnosis, on the other hand, may cause hospitalization, respiratory failure, or death.

Since symptoms look like flu or COVID-19—cough, fever, tiredness—there's a risk of misdiagnosis, especially in a busy emergency department or in patients with delayed seeking of care. This is why city officials are asking anyone in Harlem who has respiratory symptoms to call a doctor right away.

Public Health Lessons from the New York City-Harlem Outbreak

This epidemic highlights how even properly developed cities are susceptible to waterborne disease pathogens. Most building managers must keep an eye on and care for cooling towers, and the diligence can lapse. Public health professionals say that regular surveillance and more frequent testing would help stop outbreaks from running out of control into death.

The circumstance that several of the city-owned facilities were positive for tests brings questions of responsibility. If city-run cooling towers are not properly serviced, citizens can reasonably ask how well private facilities are being checked.

With remediation all but finished, health officials are guardedly hopeful that the outbreak is fading. Yet for Harlem residents, the cost is already apparent: dozens of people made ill, at least four dead, and fresh apprehension about the unseen dangers that can hide in common infrastructure.

Are NYC's Cooling Towers Actually the Issue?

The outbreak has been linked to infected cooling towers in Central Harlem, but the experts warn that cooling towers are just one source of the Legionella bacteria. Water systems like hot tubs, fountains, and even low-maintenance plumbing can spread the bacteria under favorable conditions.

Nonetheless, cooling towers have been associated in the past with some of the city's biggest outbreaks due to the way they work: vast amounts of hot water are brought into contact with air, producing mist that can travel and transfer bacteria across whole neighborhoods. As maintenance failures occur, the bacteria grow quickly, transforming these buildings into potent amplifiers of infection.

New York City has stringent measures mandating periodic testing and cleaning of cooling towers, enacted following the large 2015 outbreak in the Bronx. But enforcing them is the problem, especially with tens of thousands of towers throughout the five boroughs. The discovery that multiple city-owned buildings came back positive in this outbreak reveals not just private gaps in oversight but also gaps in municipal compliance.

So yes, cooling towers look at the center of this epidemic, but they are most accurately described as part of a larger issue: any untreated water system can become a Legionella breeding ground.

Measles Cases Surge Worldwide, Korean Health Data Flags Countries At Highest Risk For Travellers

(Credit-Canva)

Health officials around the world are warning travelers about a sharp increase in measles cases. The Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) is urging everyone to be fully vaccinated before traveling abroad, as many recent cases in Korea have been from travelers returning from other countries.

Globally, measles cases have surged, with the World Health Organization (WHO) reporting around 360,000 cases in 2024. This is largely because of a drop in vaccination rates, which were disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic

What Should Travellers Be Aware Of?

According to the KDCA, many of these infections came from countries with ongoing measles outbreaks. The number of global measles cases jumped to about 360,000 in 2024, as vaccination efforts were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The countries linked to the most imported cases are:

- Vietnam

- South Africa

- Uzbekistan

- Thailand

- Italy

- Mongolia

For travelers heading to these regions, the KDCA strongly recommends getting both doses of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. This is especially important for adults who may have missed their second dose as children.

Countries That Have The Highest Measles Cases

According to a Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) report released on 15th August, there have been 10,139 confirmed cases and 18 deaths across ten countries, a 34-fold increase compared to the same period in 2024. The countries with the highest number of confirmed cases are:

- Canada (4,548 cases)

- Mexico (3,911 cases)

- United States (1,356 cases)

Cases have also been reported in Bolivia, Argentina, Belize, Brazil, Paraguay, Peru, and Costa Rica. Sadly, there have been deaths in Mexico (14), the U.S. (3), and Canada (1). In Mexico, most of the deaths happened in Indigenous communities, which have been severely affected. Canada also reported the tragic death of a newborn.

The outbreaks are being caused by two different types of the measles virus. One type is spreading quickly among Mennonite communities in eight countries. This shows how fast the virus can move through groups that are not vaccinated. While the outbreaks have mainly been in these communities, more and more cases are now being found in other groups of people as well..

Why Do You Need Measles Vaccine?

Measles is a very contagious illness that can spread easily through the air. While most people think of it as a childhood disease, it can cause serious problems like pneumonia or brain swelling. It's especially dangerous for young children, pregnant women, and people with weak immune systems.

The MMR vaccine is the best way to protect yourself and others. Officials strongly recommend getting both doses, especially if you plan to travel. The KDCA also advises anyone who develops a fever or rash within three weeks of returning to Korea to take immediate precautions: wear a mask, limit contact with others, and tell medical staff about your recent travel before seeking care.

What Steps Have The Countries With Measles Outbreak Taken?

According to PAHO,

- Measles is still spreading in several provinces of Canada, including Alberta and British Columbia.

- In Mexico, the government has launched a mass vaccination campaign in 14 high-priority areas, with a special focus on Indigenous communities in Chihuahua, where most of the country's cases are located.

- In United States, outbreaks have been reported in 41 states, mainly among under-vaccinated populations.

- Most cases of Bolivia are in the Santa Cruz area, affecting both the general population and Mennonite communities.

- Argentina and Belize have not reported any new cases since late June.

PAHO is working with these countries to boost vaccination rates and quickly respond to new outbreaks. While travel restrictions aren't recommended, travelers are advised to ensure they are vaccinated, including young children from 6 to 11 months old, who can get an early dose for protection.

Missouri Resident Hospitalized With 97% Fatal 'Brain-Eating' Infection While Water-skiing: How Real Is The Risk At Home?

Credits: Health and me

A Missouri resident is fighting for life in the intensive care unit after contracting one of the rarest yet most deadly infections known to medicine: Naegleria fowleri, often referred to as the brain-eating amoeba. The case, traced back to waterskiing on the popular Lake of the Ozarks, has sparked renewed questions about how people can be exposed to this microscopic threat—and whether everyday activities like showering or drinking tap water could carry risks.

Naegleria fowleri is a single-celled organism that lives naturally in warm freshwater such as lakes, rivers, and hot springs. It thrives in temperatures between 77°F and 115°F, meaning it is more commonly found in waters during hot summer months when levels are low and temperatures rise.

Despite its frightening nickname, the amoeba doesn’t “eat” brains in a literal sense. Instead, when water contaminated with N. fowleri enters through the nose—often during swimming, diving, or watersports—the organism can travel to the brain. Once there, it causes primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), a devastating infection that destroys brain tissue.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describes PAM as “almost always fatal.” In fact, the fatality rate exceeds 97%, with just four survivors out of 167 confirmed cases in the United States between 1962 and 2024.

How Does the Infection ?

The key factor is nasal exposure, not ingestion. Simply drinking contaminated water does not cause illness. The amoeba must enter through the nose and reach the brain’s olfactory nerves. This is why activities like:

- Waterskiing, wakeboarding, or diving in warm freshwater

- Swimming in poorly maintained pools or splash pads

- Using contaminated tap water for nasal rinses or Neti pots

are considered riskier than simply consuming the water.

Cases have even been linked to routine activities such as bathing or showering in places where water systems were contaminated. While rare, this route of exposure is considered possible if water is forced high into the nasal cavity.

What Are the Symptoms?

Symptoms usually develop within 3 to 12 days after exposure. They begin subtly, resembling common viral illnesses, but progress rapidly:

Early: headache, fever, nausea, vomiting

Later: stiff neck, confusion, hallucinations, seizures

Advanced: coma and death, typically within five days of symptom onset

This rapid progression makes timely diagnosis extraordinarily difficult. By the time PAM is suspected, the infection is usually advanced.

How Rare Is Brain-Eating Infection, Really?

The good news is that Naegleria fowleri infections are extremely rare. In the U.S., an average of just two to three cases per year are reported, despite millions of people swimming in warm lakes and rivers.

Globally, however, cases have been documented in more than 40 countries. A review up to 2018 found 381 cases worldwide, with a shocking 92% mortality rate. The highest number of cases were recorded in the United States, Pakistan, Mexico, and India. Australia, too, has documented outbreaks, particularly in regions with warmer climates.

Is It Safe To Drink Tap-Water?

One of the most unnerving aspects of Naegleria fowleri is when it shows up in municipal water supplies. In 2024, officials in Queensland, Australia, confirmed its detection in drinking water systems in the towns of Augathella and Charleville. So should Americans be worried about catching the infection from their tap? Here’s the science:

Drinking contaminated water does not cause infection. The digestive system neutralizes the amoeba.

Nasal exposure is the risk. Taking a shower, using a Neti pot, or even children playing with hoses or sprinklers could theoretically force water up the nose.

Proper water treatment works. Adequate chlorination and maintenance of municipal systems eliminate the risk.

In the U.S., isolated incidents linked to Neti pots used with unboiled tap water have been reported, underlining why the CDC stresses that nasal rinses must use distilled, sterile, or previously boiled water.

In Missouri, the patient’s exposure was likely tied to high-speed watersports on Lake of the Ozarks during a spell of hot weather. Waterskiing increases the risk because it forces water deeply into the nasal passages.

Officials have not reported other cases connected to the lake, emphasizing just how rare the infection is, even in favorable conditions. Still, the case has heightened awareness and anxiety, particularly as climate change increases the likelihood of warmer water temperatures in many regions.

How Can You Protect Yourself?

There is no guaranteed way to eliminate risk, but health experts offer several practical precautions:

- Avoid swimming in warm freshwater during heatwaves or when water levels are low.

- Keep your head above water in lakes, rivers, or hot springs.

- Don’t dive or jump in. Water forced up the nose is the main risk factor.

- Use nose clips if you plan to submerge in freshwater.

- Stick to saltwater or properly chlorinated pools. The amoeba cannot survive in these environments.

- Use sterile or boiled water for nasal rinses. Never rely on straight tap water.

The idea of a “brain-eating amoeba” is terrifying, but public health experts emphasize that the odds of infection are extraordinarily low. Millions of people swim in lakes every year without incident.

The far greater concern, they say, is that when cases do occur, they are often misdiagnosed as bacterial meningitis until it’s too late. Public awareness, while important, should be balanced with the reality that preventive measures—like avoiding nasal exposure to untreated warm freshwater—are usually enough.

The Missouri case is a tragic reminder of just how deadly Naegleria fowleri can be, but also how vanishingly rare it is. You cannot catch it by drinking tap water, and routine showers in well-maintained municipal systems are safe. The risk only arises when contaminated warm freshwater is forced into the nose.

For now, experts say vigilance, not panic, is the right response. With simple precautions, Americans can keep enjoying summer lakes and rivers while understanding the small but serious risks that come with them.

Flu Nasal Sprays Now Available For At-Home Delivery: Know Risks, Precautions And Side Effects

(Credit-Canva, FluMist)

As harmless as it may seem, flu has been classified as high severity in 2024-25 across all ages, according to the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases (NFID). Amidst the rising number of cases, we may have an easy at-home way to deal with it.

AstraZeneca has launched FluMist Home, a new service that delivers the FLUMIST nasal spray flu vaccine right to your house. This is a game-changer, as it's the first time an influenza vaccine can be sent directly to customers for at-home use.

FLUMIST, a needle-free nasal spray, has been approved by the FDA since 2003. Now, it is also the first flu vaccine approved for people ages 18-49 to give to themselves, or for parents and caregivers to give to children ages 2-17. This new service aims to make it easier for people to get vaccinated and stay protected, especially after the last flu season was one of the worst in years.

Will This At-Home Service Help Lower Flu Cases?

According to NFID, 47 million flu related, 21 million medical visits, 610,000 hospitalizations and 27,000 deaths, which include 266 pediatric deaths happened during the flu season of 2024-25.

AstraZeneca and healthcare experts believe this new service will help more people get vaccinated. It makes flu shots more convenient and removes the need to go to a doctor's office or pharmacy.

Who Should Not Take the Flu Nasal Spray?

According to the FluMist Safety Information available on their site, you should not get the FLUMIST vaccine if any of the following apply to you:

- You have a severe allergy to the vaccine's ingredients, to eggs, or to other flu vaccines.

- You are a child or adolescent between 2 and 17 years old and are currently taking aspirin or aspirin-containing medicines. Children in this age group should not be given aspirin for four weeks after getting FLUMIST unless a doctor says it's okay.

- You are under 2 years old, as there's a higher risk of wheezing (trouble breathing) in this age group after getting the vaccine.

What Precautions Do You Need For the Flu Nasal Spray?

For the 2025-26 flu season, FluMist Home is available in 34 states. AstraZeneca plans to expand the service to all 48 states in the future. FLUMIST will still be available at doctors' offices and pharmacies. Before getting FLUMIST, it's crucial to tell your healthcare provider about all your medical conditions. This includes if you:

- Are currently wheezing or have a history of wheezing (especially if you're under 5 years old).

- Have asthma.

- Have a weakened immune system or live with someone who has a severely weakened immune system.

- Have had Guillain-Barré syndrome (a condition that causes severe muscle weakness).

- Have problems with your heart, kidneys, or lungs.

- Have diabetes.

- Are pregnant or nursing.

- Are taking antiviral drugs to treat the flu.

What Are The Side-Effects of The Flu Nasal Spray?

While most side effects are mild, FLUMIST can cause rare but serious reactions. The most common side effects are a runny or stuffy nose, sore throat, and a fever over 100°F.

Rare, serious side effects can include allergic reactions. If you experience hives, swelling of your face, lips, eyes, tongue, or throat, or have trouble breathing, seek medical help immediately.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited