- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

FDA Approves First At-Home Cervical Cancer Screening Test Kit That Could Replace Pap Smears

Credits: Canva

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently cleared and approved the at-home test for cervical cancer, possibly revolutionizing the way millions of women handle one of the most important parts of preventive health care. Created by Teal Health, the recently approved self-test device—the Teal Wand—provides an alternative, less painful method than the conventional Pap smear, seeking to make it easier, less stressful, and more accessible for cervical cancer screening.

The product, called the Teal Wand, allows women to collect vaginal swabs themselves at home—providing a potent, less painful alternative to conventional in-clinic Pap smears.

This approval represents a groundbreaking step toward breaking down long-standing barriers to screening for cervical cancer, particularly among women who find pelvic exams unpleasant, inaccessible, or culturally daunting. For them, it could be the bridge they've waited years for to early detection and timely treatment.

Cervical cancer ranks among the most preventable types of cancer owing to the existence of HPV vaccination and routine screening. However, despite increased medical capabilities, screening rates have consistently decreased since the mid-2000s. According to a 2022 study, 23% of women in 2019 were overdue for a cervical cancer screening, which was up from 14% in 2005. Almost half of all women diagnosed with cervical cancer in the United States, according to the American Cancer Society, are not current on their screenings.

This alarming trend is part of the estimated 13,360 new cases of cervical cancer and 4,320 deaths projected for 2025. The intent is for this home test to turn that trend around by reaching women where they're at—literally.

How the Test Kit Work?

The Teal Wand detects human papillomavirus (HPV), the primary cause of cervical cancer, using a self-collected vaginal swab that detects high-risk strains of the virus—just as a clinician would get a sample with a Pap smear, without the office visit and speculum.

To have access to the test, patients first have to meet with a Teal Health-affiliated provider through telehealth. If they are approved, the test is mailed to their home. After the sample has been taken, it is sent to a laboratory for processing. In case the test comes back positive for high-risk HPV, Teal Health's providers coordinate follow-up diagnostic care through in-office procedures as usual.

The advantages of this home test go beyond convenience—it could shrink the equity chasm in access to health care. According to a recent JAMA Network Open report, rural women are 25% more likely to have cervical cancer and 42% more likely to die from cervical cancer than city women. Disparities frequently are explained as a result of infrequent screening and inadequate availability of gynecologic services.

By facilitating home self-screening, the Teal Wand could assist underserved and rural communities in obtaining vital early diagnoses, possibly saving thousands of lives.

Role of HPV in Cervical Cancer

HPV is a sexually transmitted disease that most commonly resolves spontaneously. But some strains are associated with cervical and other cancers. The HPV vaccine, when given prior to sexual activity, is extremely effective in preventing illness from the high-risk strains.

As of a 2025 American Cancer Society report, incidence of cervical cancer in women between the ages of 20 and 24 decreased by 65% from 2012 to 2019 due primarily to early HPV vaccination. However, not all women are sharing in this success. Rates of cervical cancer in women in their 30s and early 40s have started to creep upward once more.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) prescribes two doses of the HPV vaccine between preteens aged 11–12, although it can begin as early as age 9. Individuals having the first dose at 15 years and older need a series of three doses. The vaccine is usually prescribed up to age 26 and up to age 45 in special situations depending on personal risk.

Worldwide, cervical cancer continues to be the fourth most frequent female cancer and is responsible for 7.5% of all female cancer deaths, based on the World Health Organization (WHO). In the United States alone, there are about 200,000 women diagnosed with cervical precancer each year and over 11,000 with HPV-related cervical cancer. Unfortunately, more than 4,000 American women die from the disease each year.

Data from an 11-year study in England also supports the efficacy of early HPV vaccination and screening. The program there averted 448 cases of cervical cancer and more than 17,000 cases of precancerous lesions, highlighting the huge promise of proactive, accessible prevention strategies.

Although the Teal Wand now must be prescribed through Teal Health's telehealth platform, the business is continuing to move toward availability through additional healthcare providers. Pricing and insurance coverage are also points of interest. Because cervical cancer screening is supported by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, coverage is also highly anticipated, which would further drive accessibility.

India Saw Over 1.5M Cancer Cases In 2025: Which States Are Worst Hit?

Credit: Canva

India has seen a significant rise in the cancer burden, with the cases rising to 1,569,793 in 2025, the government has informed the Parliament.

From more than 1.4 million in 2021, the cancer cases in the country rose to over 144,000 in the last five years, revealed Prataprao Jadhav, Union Minister of State for Health, in a written reply in the Rajya Sabha.

The increase in cases has been consistent:

- 1,426,447 cases in 2021

- 1,461,427 cases in 2022

- 1,496,972 cases in 2023

- 1,533,055 cases in 2024

- 1,569,793 cases in 2025

Similarly, cancer deaths also increased in the country -- 868,588 in 2025 from 789,202 in 2021.

The country reported about 15,000 cancer -related deaths each year:

- 789,202 deaths in 2021

- 808,558 deaths in 2022

- 828,252 deaths in 2023

- 848,266 deaths in 2024

- 868,588 deaths in 2025

Worst-Affected States And Key Reasons

Jadhav informed that bigger states with large populations have seen a major increase in cancer cases and deaths consistently in the last five years.

States with the highest estimated cancer cases in 2025 include:

Uttar Pradesh - 226,125

Bihar - 118,136 cases

West Bengal - 121,639 cases

Maharashtra - 130,465 cases

Rajasthan - 80,628 cases

States with the highest estimated cancer deaths in 2025 include:

Uttar Pradesh - 125,184 deaths

Bihar - 65,571 deaths

West Bengal - 67,093 deaths

Maharashtra - 71,696 deaths

Rajasthan - 44,402 deaths

Major reasons for the rise in cancer burden include:

- environmental factors such as industrial pollution, pesticide exposure,

- contaminated water sources, by pollutants like industrial waste, pesticides, heavy metals, and pharmaceuticals.

“The review provides a critical analysis of the current evidence, summarizing the association of water contamination, including industrial waste, pesticides, and heavy metals, with rectal and colorectal cancer,” Jadhav stated in the Upper House of the Parliament.

Cancer Care Facilities In India

Jadhav further informed that the government is tackling the growing burden by expanding cancer care infrastructure across the country.

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has implemented the Strengthening of Tertiary Care Cancer Facilities Scheme, which has approved:

- 19 State Cancer Institutes (SCI)

- 20 Tertiary Care Cancer Centers (TCCC)

Other high-quality comprehensive cancer care facilities in the country include:

- Tata Memorial Centre’s (TMC) six hospitals in Varanasi, Visakhapatnam, New Chandigarh, Guwahati, Sangrur, and Muzaffarpur

- Cancer treatment facilities in all 22 new AIIMS

- Advanced diagnostic and treatment facilities at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) at Jhajjar

- A second campus of Chittaranjan National Cancer Institute in Kolkata

- 297 Day Care Cancer Centers (DCCCs) as promised in the Union Budget 2025-26

- Free essential medicines and diagnostics at public health facilities

- Anti-cancer drugs in the Essential Drugs List at District and Sub-Divisional Hospitals

- Health insurance of Rs. 5 lakh per family annually for secondary and tertiary care under Ayushman Bharat – Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB PMJAY)

- Affordable Medicines and Reliable Implants for Treatment (AMRIT) Pharmacies providing access to affordable cancer medicines.

New dengue vaccine over 80% effective, prevents severe disease for up to 5 years

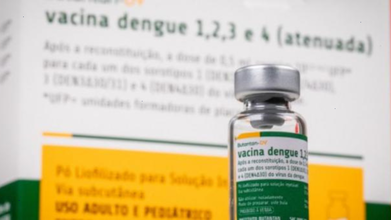

Credit: Butantan Institute

A new vaccine that targets the mosquito-borne dengue has proven to be over 80 percent effective in preventing the risk of severe disease for up to five years, according to a recent study conducted by Brazilian researchers.

The study, published in the journal Nature Medicine, confirmed that the tetravalent dengue vaccine -- Butantan-DV -- developed by the Butantan Institute in São Paulo, prevents hospitalizations and offers broader protection against all four dengue serotypes.

“This vaccine is establishing itself as a very important tool in the fight against dengue in Brazil, with the potential to contribute to reducing the circulation of the virus, in addition to individual protection,” said Fernanda Boulos, the institute’s medical director of clinical trials.

The Phase 3 Clinical Trial

The phase 3 clinical trial, conducted from February 2016 to July 2019, involved 16,235 participants between the ages of 2 and 59.

The researchers compared individuals who received a single dose of the vaccine (10,259) with those who were administered a placebo (5,976).

- The results showed

- 80.5 percent effectiveness against severe dengue cases

- no hospitalization in the vaccinated group vs 8 cases in the placebo group

- 65 percent effective in preventing symptomatic dengue

The Butantan-DV Vaccine

The Butantan-DV vaccine is tetravalent and offers protection against the four known serotypes: DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4.

The vaccine uses live viruses that have been “weakened” (attenuated) in a laboratory.

Once administered, the vaccine controls replication of these attenuated viruses in the body -- a process which induces the immune system to produce neutralizing antibodies specific to each of the four serotypes.

The vaccines create immunity specific to each serotype to enable the body to recognize and neutralize each variant individually.

The Butantan-DV vaccine was approved by the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) on November 26, 2025, for use by the Brazilian population aged 12 to 59.

The country's Ministry of Health has

- incorporated the vaccine into the national immunization program in January

- launched a pilot project to immunize 90 percent of the target population in states with high burden

- rolled out vaccination of primary care health professionals in February

Also read: Why Is Dengue Fever on the Rise Despite Vaccines?

Global Dengue Burden

Dengue is transmitted through infected mosquitoes, primarily the species Aedes aegypti.

Common Symptoms include:

- Sudden onset of high-grade fever.

- Intense headache

- Severe muscle, joint, or bone pain.

- Skin Rash that often appears 2–5 days after the fever starts

- Nausea and Vomiting

- Fatigue

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about half of the world's population is now at risk of dengue.

It estimates that:

- about 390 million dengue infections occur annually worldwide

- nearly 100 million people develop symptoms each year

The two main authorized vaccines in the world against dengue are Dengvaxia and Qdenga.

These vaccines are designed to protect against all four serotypes of the virus, with a focus on reducing severe disease and hospitalizations.

Passive Euthanasia: Harish Rana Case A Compassionate Step In Indian Healthcare

Credit: iStock

The recent decision by the Supreme Court of India allowing withdrawal of life support for a 32-year-old man in an irreversible permanent vegetative state is an important development in patient-centered healthcare.

The order follows the principles established in the landmark Common Cause v. Union of India, which recognized passive euthanasia and affirmed that individuals have the right to die with dignity. From the perspective of a critical care specialist, this decision supports ethical medical practice while protecting the dignity and rights of patients.

In modern intensive care units (ICUs), doctors use advanced technologies such as ventilators, feeding tubes, dialysis machines, and strong medications to sustain life during serious illness. These treatments are extremely valuable when there is a reasonable chance of recovery.

However, in some medical conditions—particularly severe brain injuries—patients may enter a permanent vegetative state. In this condition, the patient’s body may continue functioning with medical support, but the brain has lost the ability to produce consciousness or awareness. The patient cannot communicate, recognize loved ones, or interact with the environment, and medical science currently has no effective treatment to reverse this condition.

From a medical standpoint, continuing life support in such cases may only prolong biological survival without any possibility of recovery or meaningful quality of life. The Supreme Court’s decision acknowledges this difficult reality and allows withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment when doctors confirm that recovery is medically impossible. This approach respects the patient’s dignity and avoids unnecessary prolongation of suffering.

Harish Rana Case: Key benefits

One of the key benefits of this judgment is the recognition of dignity at the end of life. The Court has interpreted the right to life under the Constitution of India to include the right to die with dignity. In practical terms, this means that patients should not be forced to remain on life-support machines when such treatment no longer benefits them.

Medicine should focus not only on prolonging life but also on ensuring that patients are treated with respect, comfort, and compassion during their final stages of life.

The decision also supports patient autonomy, which is a core principle of ethical medical care. Individuals have the right to make decisions about their own bodies and medical treatment. The recognition of living wills or advance directives allows patients to express their wishes in advance regarding life-prolonging treatments. This ensures that medical decisions align with the patient’s values and preferences, even if the patient is no longer able to communicate.

Also read: Harish Rana Case Highlights Why Planning For A Living Will Is Important

Another important benefit is the support it provides to families. Families often experience deep emotional stress when a loved one remains in a permanent vegetative state for a long period. They may struggle with uncertainty about whether continuing life support is truly helping the patient.

The Supreme Court’s framework provides a clear and compassionate process for decision-making involving medical boards and proper documentation. This helps families make informed choices in consultation with doctors while ensuring that the decision is ethically and legally sound.

Harish Rana Case: Offers Clarity For Healthcare Workers

The ruling also offers legal clarity for doctors and hospitals. In the past, physicians sometimes feared legal consequences if life support was withdrawn, even in medically futile situations.

The guidelines established under the Common Cause judgment create a structured and transparent process for making such decisions. This allows doctors to practice responsible and ethical medicine without unnecessary legal concerns.

Also read: Passive Euthanasia: Harish Rana’s Case May Reshape End-of-life Protocols, Say Experts

Passive Euthanasia: A Compassionate Step

In conclusion, the Supreme Court’s order is a compassionate step forward in Indian healthcare. From a critical care perspective, it respects patient dignity, supports family decision-making, provides legal clarity for doctors, and encourages thoughtful end-of-life care.

Most importantly, it reminds us that the true goal of medicine is not merely to extend life at all costs, but to ensure that every patient is treated with dignity, humanity, and respect throughout all stages of life.

Also read: Harish Rana Case Brings Spotlight On How Passive Euthanasia Has Evolved Over The Years

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited