- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Dishonesty Is 'More Than A Vice', It Could Make You Sick With Anxiety

(Credit-Canva)

Being dishonest doesn’t come naturally to people, it is a learned virtue, whether out of necessity or pleasure. When kids lie, a lot of it stems from them not wanting to get in trouble, for example, breaking a household item or doing something they were told not to do like running around inside the house. However, when people do learn to tell lies, it can become like a go to tendency for many. It is easier to make something up rather than explaining complex truths.

According to a study published in the Psychological Science 2015, kids start lying around the age of two to three years old. Their habit then progresses rapidly, till the age of 3 and 7.

Not all lies are the same, some are really small and don't hurt anyone, like saying you like someone's new haircut even though you don't. These little white lies often just help keep things smooth and make people feel good. Then there are much bigger lies, like saying someone else did something wrong when they didn't, or lying to people about money. These kinds of lies can cause a lot of damage and have bad consequences for people's lives.

Stress Response of Lying

When we know that being dishonest could really hurt how others see us, the act of lying itself makes our bodies feel stressed. When we tell a lie, things start to happen without us even thinking about it. A 2015 review published in the Current Opinion in Psychology explains that our heart might beat faster, we might start to sweat a little and our mouth can feel really dry. These physical changes are what those old-fashioned lie-detector tests used to try and pick up on.

Some people don't feel as much empathy as others, and they might not have the usual stressed reaction when they lie. The American Psychological Association explains that some people can learn to control their bodies really well and might be able to lie and still pass a lie-detector test. On the other hand, someone who is telling the truth but is just really nervous about being tested might look like they are lying.

Gut-Brain Connection and Extreme Reactions

While it's not common, some people might have a really strong physical reaction to lying, like feeling sick to their stomach or even throwing up a lot. This shows how connected our gut and our brain are. When we feel really anxious, like when we are worried about getting caught in a lie, it can actually make our stomach feel bad. So, for someone who is constantly lying and worried about it, this anxiety could potentially lead to physical sickness.

Living a life where you are often not telling the truth can actually take a toll on your health over time, not just in the moment. Research has suggested that people who lie a lot might have problems like high blood pressure, their heart might beat faster more often, their blood vessels could get tighter, and they might have more stress hormones in their bodies on a regular basis.

‘Ozempic Vulva’: The Bizarre Side Effect Affecting Women’s Health

Credits: Canva

GLP-1 medications, including the popular brand Ozempic, have made headlines for their dramatic weight loss results. Initially created to treat type 2 diabetes, the medications were a favorite among those wanting to lose weight due to their ability to control hunger. Semaglutide, the active drug found in Ozempic, makes consumers full for extended periods, resulting in significant weight loss in the body. However, with increasing popularity comes an uptick in reports of unusual side effects—some of which are leaving women shocked and bewildered.

Among the most surprising and strange side effects making the rounds among users is what has been colloquially referred to as "Ozempic vulva." The condition involves a reduction of fat in the labia majora, a sagging appearance, pain during routine activities, and alteration of sexual anatomy aesthetics. Although sagging skin and loss of elasticity have long been linked to weight loss, particularly if it occurs rapidly, this particular side effect has only recently emerged.

A Reddit poster posted a first-hand account of experiencing the results for herself. Losing 44 pounds, she at first was jubilant about the outcome. "I've been extremely fortunate and I don't have any sagging skin in my belly or arms/legs that I can notice," she described. But the biggest shock was when she went for a gynecologist appointment. "Turns out I've lost all my fat pads in my vulva! She informed me my vulva is droopy and I will keep on having pain when cycling/sitting unless I undergo surgery or wear fillers," the user posted.

The Redditor also revealed that pelvic floor physical therapy was provided as a substitute for cosmetic intervention, although it would not fully reverse the deflation. Her case highlights the need to be aware of how sudden weight loss, especially from medications such as GLP-1s, can impact lesser-known parts of the body.

Medically, the vulva comprises external female genitalia, mostly the labia minora and labia majora, that act as cushioning protection. Fat loss in this region may cause a greater prominence of the pelvic bones, decrease in cushioning, and pain during exercises like cycling, running, or sitting for extended periods.

What is 'Ozempic Vulva'?

The vulva is the external female genitalia, especially the labia majora covering the inner structures. Redditors and users of internet forums have described decreased fat pads in this region after precipitous weight loss caused by GLP-1 medication. One Redditor summed up her experience thus: after losing 20 kg (44 pounds), she developed pain when she cycled or sat for long hours. A gynecologist described losing much of the natural padding around her vulva, leading to a sagging sensation and discomfort during exercise.

This trend, affectionately but aptly called "Ozempop vulva," highlights a singular and seldom-talked-about side effect of weight loss caused by medications. For most women, it's not just aesthetic; it impacts daily comfort, sex, and self-esteem.

Cosmetic treatments have evolved as a result of this trend. "Labia puffing" is an increasingly sought-after procedure for women who experience vulvar deflation. This treatment either involves the use of dermal fillers or fat transfer to add volume to the labia majora, evening out the texture and alleviating discomfort. Though effective, it is quite expensive, between $2,600 and $6,500 in America.

Healthcare professionals are urging caution. Novo Nordisk, the drug maker of Ozempic, reassured the public that patient safety is of utmost priority and assured that the medicines are to be used only for approved use in a medical setting. They also urge reporting side effects to healthcare professionals or regulatory bodies. "Treatment decisions should be made together with a healthcare provider who can evaluate the appropriateness of using a GLP-1 based on assessment of a patient's individual medical profile," said the company.

The larger context of extreme weight loss makes visible the far-reaching consequences GLP-1 drugs can have. Patients experience a range of side effects, from gastrointestinal distress to loose skin, facial fat redistribution, and effects on sexual anatomy and desire. While the physical changes are something to be admired, these effects are a reminder that extreme weight loss is not risk-free.

Incidentally, online discussions of "Ozempic vulva" have become widespread in private online forums and social media sites. Users freely exchange experiences, coping mechanisms, and aesthetic issues. Many recommend practical measures like padded bike shorts or briefer periods of exercise to alleviate discomfort. Others discuss surgical or nonsurgical treatments, although opinions are highly diverse on whether such a procedure would be desirable or required.

Medical professionals emphasize the need for integrated treatment. Sudden loss of weight must be watched over by medical professionals who can advise on likely risks to both general health and particular aspects such as the vulva. Preservation of muscle tone, padding, and elasticity of skin is essential to avoid long-term complications. For women suffering from discomfort, focused physical therapy, proper protective equipment during exercise, and well-informed consideration of cosmetic interventions may all be part of a successful management plan.

Finally, "Ozempic vulva" highlights an increasing trend on the intersection of weight-loss medication and women's health. While the drug has transformed weight control for millions of people, its unintended side effects serve as a reminder that there are risks associated with every medical intervention and that they need to be closely monitored. Education, research, and transparency with healthcare professionals are critical towards preventing such unintended outcomes.

As GLP-1 drugs become more mainstream, patients and providers alike need to be watchful. New side effects such as "Ozempic vulva" demonstrate the importance of full education on the entire range of possible changes wrought by sudden weight loss. Meanwhile, women dealing with these effects are complying with both medical advice and home remedies, being resilient in the face of an odd but increasingly prevalent health issue.

Why Your Anxiety Might Be in Your DNA: Study

Credits: Canva

Anxiety in your twenties is practically a rite of passage. Between job hunts, rent hikes, and figuring out how to cook good food, it is no wonder many young adults feel on edge. But according to a recent study published in Psychological Medicine, your worry levels might not just be about deadlines and landlords; they may also be written in your genes.

The Big Twin Reveal

The research comes from the Twins Early Development Study (TEDS), which has been tracking thousands of twins born in England and Wales since the mid-1990s. For this analysis, scientists zoomed in on over 6,400 twin pairs aged 23 to 26. By comparing identical twins (who share all their DNA) with fraternal twins (who share only half), researchers teased apart how much of persistent anxiety is genetic and how much comes from life’s curveballs.

About 60 per cent of the stability in anxiety across those years can be explained by genetics. That means if your anxiety keeps tagging along like a clingy flatmate, there is a good chance your DNA is to blame. But before you start cursing your ancestors, remember: genes set the stage, but your environment decides which play gets performed.

Anxiety’s Double Act

- Somatic distress—the jittery, tense, cannot-sit-still kind of anxiety.

- Worry-avoidance—the mental wheel of endless “what ifs” plus ducking situations that trigger them.

Even though these types look different, they share many of the same genetic roots. Interestingly, life experiences seemed to have more influence on whether someone leans toward restless fidgeting or relentless worrying.

Heritability Does Not Mean Destiny

A heritability estimate of 60 per cent does not mean you are doomed to be 60 per cent anxious. Instead, it means that across a population, 60 per cent of the differences in anxiety can be chalked up to genetic differences. The rest is life, including jobs, relationships, pandemics, or even just too much caffeine.

Speaking of pandemics, the study captured data during COVID-19, when average anxiety levels spiked. The researchers even spotted new genetic effects surfacing during the first wave, suggesting global stressors can pull fresh strings on our biological vulnerabilities. Apparently, your DNA and world events like to team up for surprise collabs.

Why This Matters

Rates of anxiety among young adults have shot up in recent years, making it a pressing public health concern. Yet most past research has focused on kids and teens, leaving the twenty-something years—arguably some of the most chaotic of all—less understood. This study fills in that gap by showing that while anxiety symptoms fluctuate in the short term, there’s a genetically shaped core that stays put.

That has big implications. For one, studies that only measure anxiety at a single point may underestimate the role of genetics, missing the stable undercurrent that persists over time. It also highlights why treatments should consider both the “nature” and “nurture” sides of the equation: biological predispositions and real-world stressors both matter.

In a nutshell, genetics play a role, but they are not the whole story. You might have been dealt some anxious genes, but lifestyle choices, coping strategies, and supportive environments can still change the plot.

Explained: Your Seasonal Flu Shot Just Got Upgraded To A Nasal Spray Vaccine That Comes to Your Door

Credits: iStock

Flu season has meant rolling up your sleeve for a shot at the doctor’s office or pharmacy. Now, that’s changing. AstraZeneca has launched FluMist Home, the first FDA-approved flu vaccine that can be delivered to your doorstep and self-administered—no needles required.

This new option, a nasal spray version of the vaccine, builds on FluMist’s two-decade track record. First approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2003, FluMist has long been available at clinics and pharmacies. But in September 2024, the FDA gave the green light for at-home self-administration. Less than a year later, the program is rolling out across 34 states in time for the 2025–2026 flu season.

The stakes couldn’t be higher, last flu season was one of the most severe in recent memory. The CDC estimates up to 82 million illnesses, 1.3 million hospitalizations, and 130,000 deaths from flu between October 2024 and May 2025. Yet vaccination rates remained low, with fewer than half of Americans getting their annual shot.

Experts say that convenience is a major barrier. Between busy schedules, limited access to clinics, and vaccine hesitancy, too many people skip protection. FluMist Home could remove at least one of those hurdles by making the process as simple as ordering online.

“People are increasingly comfortable with managing their health at home—whether through Covid-19 tests or self-injections for chronic conditions,” explains AstraZeneca. “This option takes advantage of that shift and expands access to flu vaccination.”

Do's and Don'ts Of Using Flu Nasal Spray

FluMist Home is FDA-approved for people ages 2 through 49. Adults can use it themselves, while children as young as 2 can receive it with help from a parent or caregiver.

However, it’s not for everyone. Because FluMist is a live, weakened-virus vaccine, pregnant women and people with weakened immune systems should consult their doctors before considering it. Those outside the approved age range must still rely on traditional flu shots.

How FluMist Works?

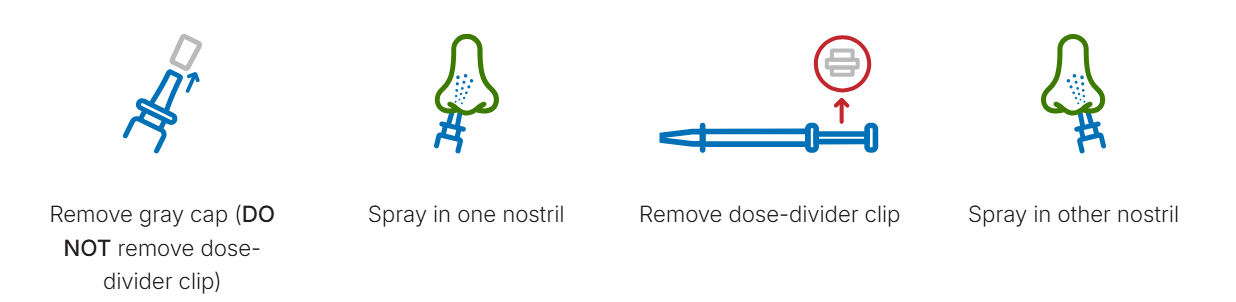

The ordering process mirrors a telehealth experience. Patients complete a brief medical questionnaire online, which is reviewed by a licensed healthcare provider before the prescription is approved. Insurance covers the cost for most users, with a flat $8.99 shipping and handling fee.

When FluMist arrives, it’s shipped in insulated, temperature-controlled packaging with ice packs to preserve stability. Each vial contains two pre-measured doses one for each nostril—separated by a clip. To administer, simply breathe normally while spraying; there’s no need to inhale deeply. A slight tickle, sneeze, or drip afterward is normal.

Patients can download a vaccination record from the online portal, and—if permission is given—the record is automatically shared with their doctor and uploaded to state vaccine registries.

Effectiveness and Safety

AstraZeneca emphasizes that FluMist Home uses the same formulation and vial as the version given in clinics. Its efficacy is on par with injectable flu vaccines, but the delivery method is needle-free.

The most common side effects are mild: runny nose, nasal congestion, and sore throat in adults. Children may experience low-grade fever. These symptoms generally resolve quickly.

Importantly, the FDA required AstraZeneca to conduct a usability study before approval. Results showed that 100% of participants were able to correctly self-administer the full dose without healthcare supervision.

How This Helps Tackle The Vaccination Gaps?

Needle-free, self-administered vaccines aren’t just about convenience—they may be critical in improving uptake. FluMist Home joins a growing trend of decentralizing preventive healthcare, putting tools directly into patients’ hands.

Historically, nasal spray flu vaccines were popular among children and adults who disliked shots. Now, offering a home option could further broaden access. As public health experts warn about the dangers of simultaneous flu, RSV, and Covid-19 waves, innovations like FluMist Home might play a pivotal role in reducing strain on hospitals.

The CDC notes that every additional percentage point increase in vaccination coverage can save thousands of lives during peak flu seasons. By lowering logistical barriers, FluMist Home could help close that gap.

Nasal Spray vs Shot: What Works Better?

The differences between FluMist and injectable vaccines come down to technology. Traditional flu shots use either killed viruses or specific proteins to teach the immune system how to respond. FluMist, by contrast, uses a live but weakened influenza virus. Both methods are proven to work, but some patients respond better to one than the other.

For people who avoid shots due to fear or discomfort, FluMist offers a gentler alternative. For children, especially, a quick nasal spray can mean less stress and higher compliance.

Could Nasal Sprays Be the Future of Vaccination?

The rollout of FluMist Home may be a harbinger of bigger changes. The pandemic normalized home-based care and accelerated acceptance of mail-order biologics, self-testing kits, and virtual consultations. Vaccines, once the exclusive domain of clinics, could follow suit.

Some researchers are already working on shelf-stable, oral, or patch-based vaccines that could one day make prevention even more accessible. For now, FluMist Home represents a significant step forward in modernizing how people protect themselves during flu season.

Useful Tips for Patients

Storage: Keep FluMist refrigerated (35°F to 46°F) until use.

Timing: Administer early in flu season for maximum protection.

Recordkeeping: Save your vaccination confirmation for medical records and travel purposes.

Disposal: Packaging materials are largely recyclable; chill packs can be reused.

FluMist Home gives people a practical, needle-free, at-home option to stay protected against the flu. While it’s not suitable for everyone, its convenience could boost vaccination rates at a time when respiratory viruses remain a major public health threat.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited