- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Is It Safe To Get A Mammogram During Pregnancy?

Image Credit: Health and me

Pregnancy is accompanied by a lengthy list of do's and don'ts—take prenatal vitamins, no alcohol, exercise carefully, and eat well. But what about when an unplanned health issue presents itself, such as the necessity for a mammogram? For most women, this might not even be something they think about until they are in a position where breast cancer screening is an option.

Perhaps you're over 40 and in need of your yearly mammogram, or perhaps you have a history of breast cancer in your family and you want to keep your screenings current. More emergently, you've found a lump in your breast. So, can you have a mammogram when pregnant? The answer is yes, but there are several things to consider.

Pregnancy creates substantial hormonal changes that affect the body, as well as breast tissue. Estrogen and progesterone's rise causes the breasts to expand and condition to produce milk, which results in denser tissue. This increased density is more challenging to detect any abnormalities with using mammograms. Even post-delivery, should the woman be breastfeeding, milk-filled glands can also make the breasts denser and, as a result, make mammogram readings less clear.

While 3D mammograms have improved imaging technology to help navigate dense breast tissue, doctors often suggest postponing routine screening mammograms until after pregnancy if there are no symptoms or high-risk factors. However, if a lump or abnormality is found, your doctor may recommend immediate diagnostic imaging.

When Is a Mammogram Necessary During Pregnancy?

Mammograms are not done routinely if a woman becomes pregnant, yet there are specific situations where one might be unavoidable. Breast cancer in pregnancy does occur—1 in 3,000 times—but it's not common. If a lump is detected by a woman, she has constant breast pain and no explanation, or she is at high risk (e.g., strong history of breast cancer in her family or genetic defect such as BRCA1 or BRCA2), a physician will order a mammogram.

The process itself takes very little radiation exposure. The radiation employed by a mammogram is concentrated on the breast, and there is little to no radiation that reaches other areas of the body. A lead apron is also placed over the belly to shield the unborn child.

Alternative Breast Imaging Options During Pregnancy

For pregnant women requiring breast imaging, physicians may initially suggest an ultrasound. In contrast to a mammogram, an ultrasound is not done with the use of radiation and is deemed safe for pregnant women.

An ultrasound of the breast can establish whether a lump is a fluid-filled cyst or a solid tumor that needs further investigation. Yet ultrasounds are not always diagnostic, and in certain instances, a mammogram or biopsy is needed to determine or rule out cancer.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is also an imaging choice but has some drawbacks. The majority of breast MRIs employ a contrast material called gadolinium, which is able to pass through the placenta and to the fetus. Although risks are not entirely clear, physicians usually do not use MRI with contrast unless necessary. Some practitioners may offer an MRI without contrast as an option.

What If You Find a Lump In Your Breast During Pregnancy?

Breast changes throughout pregnancy are normal, but finding a lump should never be taken lightly. If you notice a lump, alert your medical provider right away. They will conduct a clinical breast exam and potentially have you get an imaging study such as an ultrasound or mammogram to see whether anything needs to be done.

If imaging indicates a suspicious mass, a biopsy can be suggested. Core needle biopsy is the most frequently used and is safe during pregnancy. It consists of numbing the skin with local anesthetic and inserting a hollow needle into the area to obtain a small sample of tissue to be tested.

Breast Cancer Treatment During Pregnancy

In the extremely uncommon event of a diagnosis of breast cancer while pregnant, therapy will be determined by the nature and extent of cancer and by how far along in pregnancy one is. The most frequent form of treatment is surgery—either mastectomy (surgical removal of the entire breast) or lumpectomy (surgical removal of the lump)—which is usually safe while pregnant.

Chemotherapy is also possible but usually only attempted after the first trimester, when it can damage developing fetal tissue. Radiation therapy is not used during pregnancy and is typically deferred until after giving birth. Hormonal therapy and targeted therapies are also omitted until after giving birth.

Can I Get a Mammogram While Breastfeeding?

Yes, you can have a mammogram while you are breastfeeding. The radiation in a mammogram does not impact breast milk or hurt the baby. But breast density is still high during lactation, and this might complicate detection of abnormalities. To enhance image quality, physicians usually advise breastfeeding or pumping 30 minutes prior to the mammogram.

Routine screening mammograms are usually delayed in pregnancy unless there is a high-level concern.

If a lump is detected, an ultrasound is typically the initial imaging study done, with a mammogram being a consideration if additional assessment is necessary.

- Pregnancy mammograms utilize minimal radiation and are safe when required.

- Breast MRI with contrast is usually avoided in pregnancy.

- Breast biopsy, when necessary, is safe during pregnancy.

If breast cancer does develop during pregnancy, there are available treatment options that can be adjusted to keep the mother and infant safe.

Pregnancy is a period of significant change, and health issues particularly those involving breast health, are anxiety-provoking. Routine mammograms are typically postponed until after giving birth, but diagnostic testing can be done if necessary. The best you can do is discuss changes you notice in your breasts with your healthcare provider in an open manner. Early detection and prompt treatment can make a very big difference in the health of both mother and fetus.

From First Period to Menopause: How Your Cycle Evolves Over the Years | Women's Day Special

Considered to be a key symbol of fertility and reproductive years, a woman's menstrual cycles are an integral and natural part of her life. However, they are more than just a monthly event, but instead a reflection of their hormonal, metabolic and even emotional health.

Due to genetics and other lifestyle factors, every woman experiences their cycle differently, which leaves many second-guessing about their hormonal balance, thyroid function, metabolic health, stress levels and even sleep quality.

Dr Archana Dhawan Bajaj, Gynaecologist and IVF Expert, Nurture exclusively tells Healthandme: "Knowing these patterns would guide people to understand when the changes are normal worry and when they are upheaval of a problem. Although the cycles vary among individuals, some features of such cycles are common between individuals, including the length of the cycle, flow, symptoms, as well as consistency, which are used to determine a normal state at various ages.

Here is what you should know and keep an eye out for during each phase:

The Early Years: Finding a Rhythm

Dr Maya PL Gade, Consultant, Gynaecology & Obstetrics at Kokilaben Hospital tells Healthandme: "In the first 2–3 years after menarche i.e. your first period, irregular cycles are common. Nearly 40–50 percent of adolescents do not ovulate consistently at first. The brain–ovarian hormonal axis is still maturing, so cycles may be longer than 35 days (than their typical 28 day monthly cycle) , bleeding may be heavy and cramps can feel intense.

Dr Rohan Palshetkar, Consultant IVF Specialist, Bloom IVF also warned that bleeding for more than 7–8 days continuously, soaking pads every 1–2 hours or going more than 90 days without a period may signal hormonal imbalance, clotting disorders, or conditions like PCOS.

He told Healthandme: "It is important to note that early teen cycles often happen without ovulation. For teenage girls, developing stable cycle will take some time due to ovaries adjusting to produce hormones. It is only in their late teens and early 20s that the girls will get the cycles more regular."

Normal Menstrual Cycle: According to Dr Bajaj, a normal cycle can be between 21 and 45 days. During bleeding, flow can be light, heavy, and cramps, mood swings, or even fatigue may accompany the adaptation of the organism to the hormonal changes.

Abnormal Menstrual Cycle: The expert explained: "Extensive bleeding, which needs the replacement of sanitary items every hour to two hours, long than seven or eight days, excruciating pain, or lack of periods in several months could be a sign of hormonal imbalance, thyroid complications, or polycystic ovarian syndrome."

20s and Early 30s: The Stable Phase

Talking about the post-teenager phase, Dr Gade said: "For many women, this is when cycles become more predictable, typically every 21–35 days, with 3–7 days of bleeding. Ovulation is more regular and PMS patterns are clearer. However, this is also the stage where lifestyle has a strong impact."

"Fertility is also at its peak in the 20s and early 30s, making it easy for women in this age group to become pregnant. With childbirth and breastfeeding, the chances of cycle alteration, its flow and length are high," Dr Palshetkar added.

Dr Gade also noted that high stress, poor sleep, intense exercise, crash dieting, thyroid disorders, or PCOS can disrupt ovulation and any sudden irregularity in this decade is often the body’s early warning system. A consistently painful period is also not “normal”, it may point to endometriosis or adenomyosis, both of which are frequently underdiagnosed,"

Keeping this in mind, it is essential for girls in their 20s and early 30s to track their period for regularity and flow, Dr Palshetkar advised.

Normal Menstrual Cycle: Dr Bajaj told this publication: "The average period to undergo a cycle is 21 to 35 days at an average of three to seven days with a moderate flow. The symptoms can be mild and include bloating, cramps or breast tenderness that can be easily treated."

Abnormal Menstrual Cycle: Talking about abnormal alterations, the gynaecologist said: "Excessive menstrual bleeding, cramps that impair normal life or inter-menstrual bleeding may be some of the early signs of endometriosis, fibroids, hormonal disruption or chronic stress."

Late 30s to 40s: The Hormonal Transition

Dr Gade explained: "Fertility begins to decline gradually after 35 due to reduced ovarian reserve. Cycles may shorten initially because ovulation happens slightly earlier. As women move into perimenopause, a transition that can last 4–8 years, hormone levels fluctuate unpredictably. Estrogen doesn’t simply drop; it rises and falls unevenly.

"This explains why many women notice heavier bleeding, clotting, worsening PMS, new-onset anxiety, sleep disturbances or cycles that skip months and then return. Studies suggest that up to 90 percent of women experience noticeable cycle changes during this phase.

"Importantly, very heavy bleeding at this stage should not be ignored. It can sometimes be linked to fibroids, endometrial thickening, or other structural changes in the uterus."

Moreover, Dr Palshetkar also warned: "For some, there is a noticeable and increasing gap between periods before menopause. Fertility decline is a reality in the age group, though it is not impossible to get pregnant.

Normal Menstrual Cycle: Dr Bajaj elaborated to Healthandme: "The hormonal shifts at this age may make the cycles a bit shorter or longer. Flow can either become thicker or thinner and premenstrual symptoms can be more pronounced as the body slowly transitions into perimenopause."

Abnormal Menstrual Cycle: Additionally, she said: "Very heavy bleeding, very prolonged intervals between the periods, bleeding following intercourse or sudden spotting between menstruation may be considered an issue, as these can be indicators of hormonal disorders, the presence of fibroids, or other gynecological problems."

Menopause: A New Baseline

Ultimately, Dr Gade detailed: "Menopause is diagnosed after 12 consecutive months without a period, with the average age globally around 50–51 years. Hormone levels stabilize at lower levels, and while periods stop, symptoms like hot flashes, vaginal dryness, bone density changes, and metabolic shifts may appear."

"Post-menopause, a woman’s reproductive health sees a significant decline of estrogen levels, fertility, and inability to produce any eggs. However, it still sees noticeable hormonal fluctuations and resultant health troubles.

"Facing PMS-like symptoms like mood swings and irritability is not uncommon. Medical attention is required when women notice severe pain or very heavy bleeding at

any age after menopause.

"The changes and evolution in the menstrual cycles are proof of her complete health during the course of the life she lives. And it impacts the way she lives or can live through her lifetime," Dr Palshetkar added.

Normal Menstrual Cycle: Lastly, Dr Bajaj said: "Prior to menopause, the cycles can become irregular since of the hormonal fluctuations and some symptoms like hot flushes, sleeping problems or mood swings can appear."

Abnormal Menstrual Cycle: While she noted that slight spotting is possible post-menopause due to fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone levels, the expert advised: "Post-menopausal vaginal bleeding is regarded as abnormal and needs to be medically examined because it may be due to underlying health conditions that must be addressed."

Hailey Bieber Revealed How A Mini Stroke At 25 Led To Her Discovering A Hole In Her Heart

(Credit - SHE MD Podcast/haileybieber/Instagram)

Hailey Bieber recently opened up about a mini stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA) she experienced when she was just 25. In an episode of the SHE MD podcast, hosted by Mary Alice Haney and Dr. Aliabadi, Hailey discussed how the mini stroke actually led her to find out an even bigger issue in her heart.

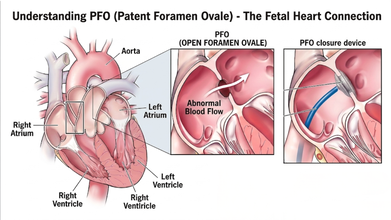

Dr. Aliabadi, a world-renowned OBGYN based in Los Angeles, who is also Hailey’s doctor, explained that this ordeal led Hailey’s medical team to discover a PFO, also known as a hole in her heart

In the interview, the founder of Rhode Beauty detailed how she had the classic stroke symptoms and said: “[My] whole right side of my arm went numb. I couldn't speak. Like my words were coming out all jumbled. The right side of my face was drooping. It was like a classic stroke symptom”

She explained that the reason why her team called it a mini stroke is because it ended within 31 minutes. By the time she reached the hospital, she didn’t need any clot busting medicine or procedure.

What Caused Hailey Bieber’s Mini Stroke?

Dr. Aliabadi explained that Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO) is extremely common phenomenon and a majority of people go through life never knowing they have it.

The Cleveland Clinic explains that the PFO is a small flap or opening between the upper chambers of your heart that everyone has. However, it usually closes up before the age of three. Most of the time, a PFO doesn’t cause symptoms and would not need treatment; however, in rare cases, it could lead to a stroke and or a TIA.

How Was Hailey’s Heart Condition Diagnosed

Hailey explained that her heart is slightly tilted in her chest and standard echocardiogram couldn't see the opening at first which led ER doctors to be unable to detect it.

As a result, she had to see a specialist for a Transcranial Doppler test. Doctors listened to the sound of blood "shunting" (moving the wrong way) through her heart to finally confirm the hole was there, which was much larger than they expected.

Also Read: Women Heart Symptoms Could Differ From Men, Explains Expert

What Is Transcranial Doppler Test?

According to the Cleveland Clinic, it is an ultrasound test that uses sound waves to detect conditions that affect blood flow to and within your brain. It can detect strokes caused by blood clots, narrowed sections of blood vessels, and numerous other heart-related issues.

How Did They Fix Hailey Bieber’s Heart?

Instead of an open-heart surgery, doctors performed a modern, minimally invasive procedure on Hailey's heart. She detailed the procedure where the doctors reached her heart through a vein in her groin. They threaded a tiny "button" made of metal and Teflon up to her heart and used it to securely plug the hole.

Hailey also learned she has some genetic factors that put her at a higher risk for blood clots and inflammation. Despite suffering a life-altering stroke, she views it as a "blessing in disguise" as it led her to find these issues early.

Now, she manages her health through a clean lifestyle, focusing on sleep, exercise and keeping her heart inflammation low.

Reducing Mother-To-Child HIV Transmission To Zero Key To End AIDS In India: Experts

Credit: iStock

Reducing mother-to-child HIV transmission, also called vertical transmission, to zero is crucial to achieve the end AIDS target by 2030 in India, in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, said experts.

At the 17th National Conference of the AIDS Society of India (ASICON 2026), health officials and experts together deliberated on the progress made in the country against HIV and also called for a stronger last-mile effort to eliminate AIDS from the country.

While India has made a major reduction in vertical HIV transmission, with just 0.7 percent of infant diagnoses. But the experts stressed the need to further reduce it to zero.

From 25 percent in 2020, the vertical transmission of HIV has come down to 11.75 percent in 2023, according to Dr. Glory Alexander, President of AIDS Society of India (ASI).

“Before treatments were available to prevent vertical transmission, the risk of a newborn acquiring HIV in India ranged from 15 percent to 45 percent. The risk was nearly 45 percent among infants who were breastfed,” Dr. Alexander said.

She attributed the reduction to the introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and implementation of HIV prevention and treatment guidelines.

"The government has successfully reduced the rate of infant HIV diagnosis (risk of a child getting infected with HIV due to vertical transmission) to 0.71 percent. We need to further reduce it to zero to eliminate vertical transmission of HIV,” Dr. Alexander added.

Intensifying Last-Mile Approach

India reportedly has 27-29 million pregnancies every year.

As per the latest National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) report, 83 percent of all pregnant women are tested for HIV, and 78 percent of all pregnant women are tested for syphilis in India.

“Out of an estimated 19,000 pregnant women who might be living with HIV in India, over 16,000 were reached by the government-run program and linked to services -- half of them were newly diagnosed with HIV,” Dr. Alexander said.

NACO runs 794 antiretroviral therapy centers across the country and provides free HIV treatment to 18 lakhs people with HIV.

NACO's over 700 “Suraksha Sewa Kendras” also provide preventive services for people who are at risk of acquiring HIV.

Dr. Ishwar Gilada, Emeritus President of AIDS Society of India (ASI), called India's progress "commendable."

"But to end AIDS, the last mile approach has to be accelerated and intensified manifold,” the expert said.

Increase HIV Testing Manifold

Dr. Gilada stressed the need to "ensure that all key populations know their status, and those with HIV are linked to treatment, care, and support services and remain virally suppressed".

If a person with HIV is virally suppressed, then there is zero risk of any further HIV transmission, as per the WHO, he added.

Indian data shows 9-43 times higher HIV rates (as compared to the general population) among key populations, such as men who have sex with men, transgender people, sex workers, people who inject drugs, among others.

These key populations are hard to reach, which warrants community-led and science-backed approaches, said Dr. Gilada.

Reducing Advanced HIV Disease

Despite commendable progress in India’s HIV response, there is a huge number of cases of advanced HIV disease (AHD) -- about one third of all people living with HIV in the country, the experts said.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines AHD as a CD4 count less than 200 cells per cubic millimeter/ or WHO stage 3/4 in adults/adolescents, and all children less than 5 years old.

It indicates a severely weakened immune system, high mortality risk, and vulnerability to infections like TB and cryptococcal meningitis.

AHD cases in India are majorly among those who are HIV infected but are not on lifesaving antiretroviral treatment.

"This could be because HIV infection is undiagnosed in people until they present with opportunistic infections to healthcare centers, or they were not able to adhere to the treatment for a range of reasons,” said Dr Trupti Gilada, Joint Secretary, AIDS Society of India (ASI).

TB, which is preventable and treatable, is the most common opportunistic infection among people with HIV.

Another concern is the rising antimicrobial resistance in HIV patients. Studies show that people with HIV are 2-3 times more likely to get drug-resistant forms of TB.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited