- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Cancer Drug Leucovorin Shows Potential In Autism Treatment

Credit: Canva

Researchers exploring the underlying causes of autism have identified a surprising potential treatment—a widely used cancer drug. Leucovorin, a medication typically prescribed to reduce chemotherapy side effects, has demonstrated promising effects in improving autism symptoms. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects communication, social interactions, and behavior.

Nonverbal Children Showed Improvement

Over the past 13 years, Dr Richard Frye, a pediatric neurologist from Arizona, has conducted multiple studies suggesting that leucovorin could help children with autism make significant developmental progress. Notably, some nonverbal children who received the drug have started speaking for the first time. Speaking to NYPost, Dr Frye said, "There isn't a single pill to cure autism, but leucovorin has helped many children. Rising Autism Rates and the Need for New Treatments."Autism Has Increased By 175% In US

The prevalence of autism diagnoses has surged in recent years, increasing by 175% between 2011 and 2022 in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 1 in 36 children in the U.S. is now on the spectrum.

Experts believe this increase is due to greater awareness, improved diagnostic criteria, and expanded screening efforts. However, environmental factors and policy changes may also play a role, underscoring the need for innovative treatment options like leucovorin.

How Leucovorin May Help

Dr. Frye’s interest in leucovorin’s potential stemmed from research in the early 2000s that identified unusual neurochemical patterns in children with autism. Scientists discovered that many children with neurodevelopmental disorders had low levels of folate (vitamin B9) in their brains, a condition known as cerebral folate deficiency (CFD).Further studies revealed that over 75% of children with autism had folate receptor alpha autoantibodies, which hinder folate transport to the brain. In contrast, only 10% to 15% of children without autism exhibited these antibodies.

To counteract this deficiency, Dr Frye began treating his patients with leucovorin, a form of folinic acid that bypasses the folate transport blockage caused by these receptors to counteract this deficiency. He finally concluded that the drug may help restore proper folate levels in the brain, leading to noticeable improvements in cognitive and social development.

Promising Outcomes In Clinical Studies

Many children who received leucovorin have shown remarkable progress. In one case, a child who previously sat in a corner experiencing seizures began interacting with family members and playing with a sibling after starting treatment. While not a cure, the improvements were significant. Dr Frye and his team continue to investigate leucovorin’s broader effects, particularly on social interaction and comprehension. Preliminary findings suggest that older children receiving the drug exhibit a richer vocabulary, improved language skills, and enhanced understanding of speech.WHO Reclassifies Hepatitis D As Carcinogenic, Warns Of 2-6% Rise In Liver Cancer Risk

Credits: Canva

The World Health Organization (WHO) has reclassified Hepatitis D as carcinogenic to humans, placing it in the same league as Hepatitis B and C—both already known for causing liver cancer. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), individuals living with both Hepatitis B and D face a 2–6 times higher risk of developing liver cancer than those infected with Hepatitis B alone.

This reclassification isn’t just a semantic shift. It’s a wake-up call. One that pushes governments, healthcare systems, and international partners to urgently act on viral hepatitis—a public health crisis hiding in plain sight.

Every 30 seconds, someone dies from liver cancer or severe liver disease caused by hepatitis. Hepatitis—especially the B, C, and D types—can silently wreak havoc on the liver, often going undiagnosed for years until irreversible damage sets in. Over 300 million people globally are currently living with chronic hepatitis infections, but the vast majority don’t even know they’re infected.

In 2022 alone, 1.3 million deaths were linked to complications from hepatitis-related liver cirrhosis and cancer. And yet, test and treatment coverage remains worryingly low.

What Makes Hepatitis D Especially Dangerous?

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is unique in that it cannot survive without Hepatitis B virus (HBV). It’s a co-infection that worsens outcomes dramatically. When someone already infected with HBV contracts HDV, the risk of liver inflammation, cirrhosis, and cancer accelerates significantly.

The IARC's move to declare HDV carcinogenic marks a pivotal moment. It helps shape global policy, medical research priorities, and public health campaigns focused on better diagnostics and innovative treatment.

WHO’s New Guidelines and Renewed Goals

In response to this new classification, WHO released comprehensive diagnostic guidelines for Hepatitis B and D in 2024. The agency is also closely monitoring emerging treatments for hepatitis D, which currently remain limited.

Hepatitis C remains the easiest to cure—with an average treatment time of 2 to 3 months. Hepatitis B, however, requires lifelong oral medications and ongoing monitoring. Hepatitis D treatments are still evolving, but effective disease control hinges on early testing, accurate diagnosis, and access to care. While there’s momentum, the reality remains mixed.

The number of countries with national hepatitis action plans rose sharply from 59 in 2020 to 123 in 2025—a good sign. Similarly, hepatitis B birth-dose immunization coverage increased to 147 countries in 2022, up from 138 but these gains are offset by glaring gaps:

Only 13% of those with Hepatitis B and 36% with Hepatitis C had been diagnosed by 2022

Treatment coverage was just 3% for Hepatitis B and 20% for Hepatitis C—well below WHO’s 2025 goals of 60% diagnosed and 50% treated

Just 27 countries have integrated Hepatitis C services into harm reduction centers, despite the known link with injectable drug use

Clearly, awareness and infrastructure haven’t kept up with the scale of the problem.

If current WHO targets are met by 2030, the world could prevent 9.8 million new infections and save 2.8 million lives but we’re not there yet. To close the gap, countries must:

- Expand hepatitis services into primary care systems

- Integrate testing and treatment with HIV and harm reduction programs

- Boost domestic investment in hepatitis programs as global donor support wanes

- Ensure access to affordable medicines and diagnostics, especially in low- and middle-income countries

And just as critically—reduce the stigma surrounding hepatitis testing and treatment

As WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus put it, “Every 30 seconds, someone dies from a hepatitis-related severe liver disease or liver cancer. Yet we have the tools to stop hepatitis.”

WHO isn’t working alone. The organization has joined forces with Rotary International and the World Hepatitis Alliance to boost local and global awareness campaigns. This multi-stakeholder approach underlines the need for government support, civil society involvement, and community leadership in the fight to eliminate hepatitis.

Efforts are underway to scale hepatitis services within existing healthcare platforms. Currently, 80 nations have integrated hepatitis into primary healthcare; 128 have folded hepatitis into HIV programs. These integrations make the most sense both financially and logistically, especially in countries grappling with strained health resources.

Understanding the Hepatitis Alphabet

Hepatitis A: Spread through contaminated food or water; usually resolves without lasting damage

Hepatitis B: The world’s most common liver infection; can become chronic and life-threatening

Hepatitis C: Spread through blood contact (e.g., shared needles); highly treatable but often undiagnosed

Hepatitis D: Only affects those with hepatitis B; now classified as carcinogenic with much higher cancer risk

Hepatitis E: Often resolves on its own, but can be dangerous in pregnancy

Among these, B, C, and D pose the highest risk of chronic infection, cirrhosis, and cancer.

The WHO’s reclassification of Hepatitis D as carcinogenic isn’t just a scientific update—it’s a call to arms. One that highlights the need to shift from reactive care to preventive action.

The tools exist, the data is clear. What’s missing is the political will, public awareness, and resource allocation to turn this silent killer into a preventable, treatable condition—no matter where someone lives.

If countries act now—boldly and collaboratively—millions of lives can be saved. And that’s a global health win the world can’t afford to miss.

Air Quality Health Index Explained: Why India’s AQI Needs An Overhaul And Include Death Risk

Credits: Canva

We often hear about Delhi’s "very poor" air days, but what does that really mean for your health? A new study, published in IOP Science, titled: A framework for city-specific air quality health index: a comparative assessment of Delhi and Varanasi, India, says it may mean a lot more than just coughing, breathlessness or a minor discomfort. In fact, on some days, it could mean a higher risk of death.

India’s current Air Quality Index (AQI), launched in 2015, was designed to simplify pollution levels and make it easy for people to understand the quality of the air they breathe. But a group of researchers now argue that this national index is outdated and dangerously vague when it comes to the actual health risk, particularly, the short-term risk of premature death.

Their recommendation? Replace the one-size-fits-all AQI with a more precise, city-specific Air Quality Health Index (AQHI) that includes the risk of excess mortality. This, they say, will allow both the public and policymakers to take air pollution far more seriously.

India's Air Quality Has Already Crossed WHO Limits

India’s worsening air quality is not just falling short of domestic health warnings, it is also regularly violating global safety standards.

ALSO READ: India Air Pollution Levels Surpass UN's Safety Standards

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), India’s air pollution levels consistently surpass safe thresholds, posing a grave public health threat. This is not just a concern for Delhi, although it remains one of the world’s most polluted capitals. The issue extends far beyond its borders.

Dr. Maria Neira, Director of WHO’s Department of Environment, Climate Change and Health, recently commented on this worrying trend. “There is a study which shows that we always focus on New Delhi when it comes to pollution, but I am afraid it is almost all of India where WHO standards on AQI are not implemented,” she said.

Dr. Neira warned that while being slightly off WHO norms is still problematic, many Indian cities now drastically exceed safe levels. The solution, she said, lies in stronger political commitment to clean air initiatives and faster implementation of existing policies.

40 Extra Deaths on a Single 'Severe' Pollution Day

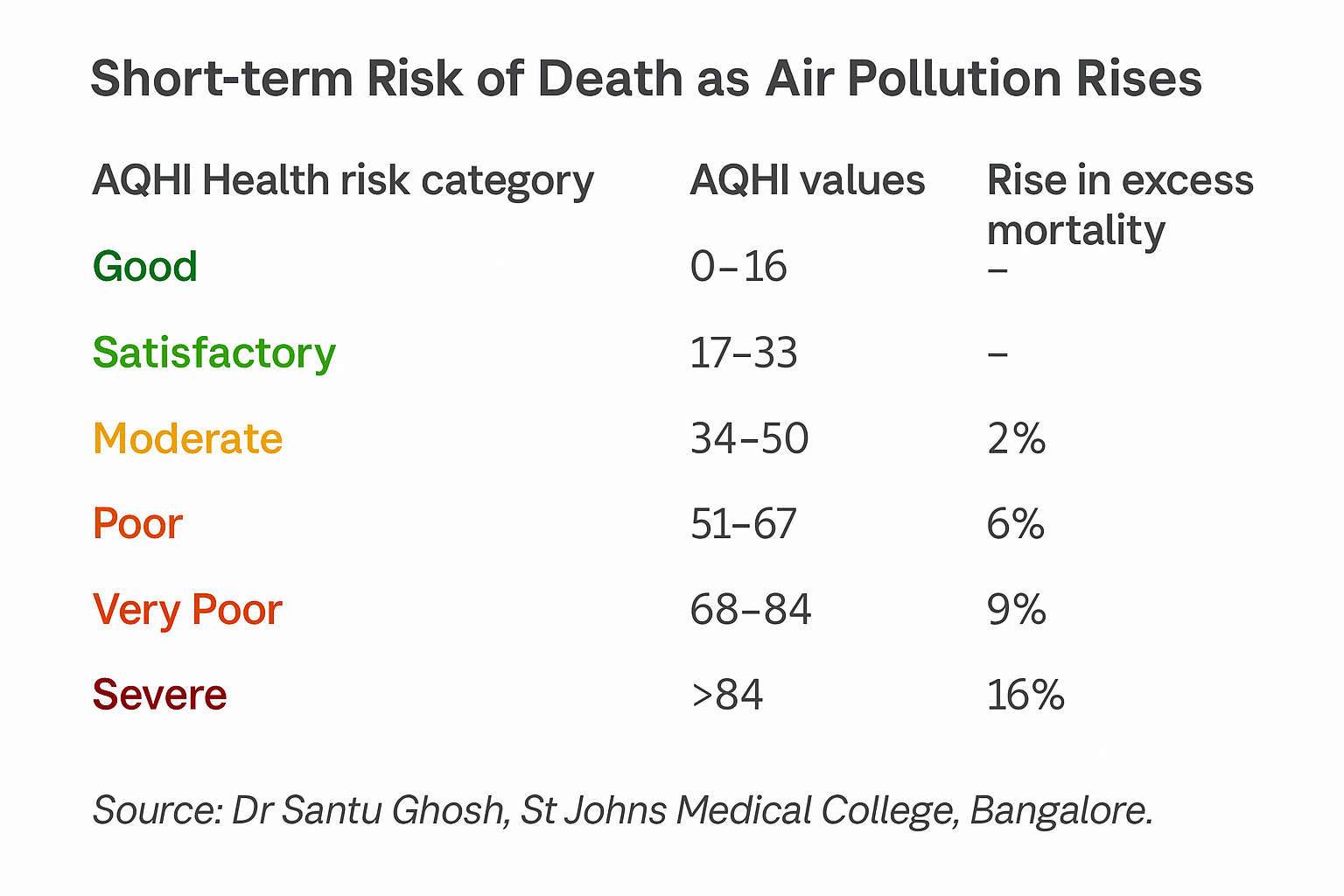

According to the new study, published on 22 July, this year, led by Dr Santu Ghosh from St John’s Medical College in Bengaluru, a severe pollution day in Delhi could lead to 16% higher mortality. In simple terms, if Delhi records an average of 250 deaths in a day, a severe air day may result in 40 additional deaths.

That figure isn’t a vague long-term statistic, it reflects the immediate health impact of pollution. And yet, the current AQI doesn’t communicate this. A severe pollution reading today only warns that it "affects healthy people and seriously impacts those with existing diseases."

By contrast, the proposed AQHI categorizes air days based on the short-term increase in excess mortality. Even a ‘moderate’ air quality day, according to this new index, comes with a 2 percent rise in daily deaths, and this risk increases as pollution worsens.

Air Pollution: The India Problem

India’s air pollution is not just a seasonal or a regional issue. It is a year-round crisis that impacts vast sections of the population, especially in densely populated urban centres.

Several regions across the country routinely record AQI values far beyond safe limits set by both Indian authorities and international health agencies. The WHO warns that even brief exposure to high levels of pollutants can trigger serious health issues, something that millions of Indians face daily.

How AQHI Works and Why It’s Different

Unlike the AQI, which uses a 0 to 500 scale, the AQHI operates on a simpler 0 to 100 range. More importantly, it’s tailored to each city using local data on pollution levels and mortality rates.

The authors analyzed air pollution and mortality data from two cities: Delhi and Varanasi. Both were chosen for their political and public health relevance, Delhi being the national capital and Varanasi being the Prime Minister’s constituency, notes the study.

The AQHI makes a strong case that even the same pollutant levels affect cities differently.

For instance, if the PM2.5 level is 120 micrograms per cubic metre (a serious pollution level), the AQI might show 300 for both Delhi and Varanasi. But the AQHI, based on local health data, would show 46 for Delhi and 64 for Varanasi.

In AQHI terms, Delhi’s reading would be ‘moderate,’ while Varanasi’s would be ‘poor’, reflecting a real difference in public health impact.

Air Pollution Doesn’t Just Affect the Lungs

The WHO also notes that the main pathway of exposure to air pollution is through the respiratory tract, and that breathing in polluted air leads to inflammation, oxidative stress, immune suppression, and even cellular mutations throughout the body.

This can damage multiple organs, including the lungs, heart, brain, and more. WHO categorises air pollution as a risk factor for all-cause mortality, as well as for specific diseases such as stroke, ischaemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), lung cancer, pneumonia, and even cataract. Pregnant women and children are especially vulnerable to its effects.

Why the Current AQI Falls Short

India’s AQI uses health advisories from the US Environmental Protection Agency due to a lack of Indian studies when it was first launched. The 2015 document that introduced it even acknowledges this limitation. Since then, more local data has become available, but the AQI has not been updated.

The AQI also does not mention mortality risk in any of its categories. At most, it notes minor breathing discomfort or effects on sensitive groups. But research shows that air pollution is the second leading risk factor for non-communicable diseases in India. It is directly linked to heart attacks, strokes, and respiratory diseases, all of which can become fatal quickly, especially in older adults or those with pre-existing conditions.

What Can Be Done, Suggest Researchers

Dr Sagnik Dey from IIT Delhi, one of the authors, compares this to tobacco: "With smoking, the blame can be put on the individual. But with air pollution, it’s a public issue, the government has to step in."

One major challenge is access to mortality data, which is held by the Ministry of Health and the National Centre for Disease Control. However, researchers argue that once this data is made available, generating AQHI cut-offs for hundreds of Indian cities would take only a few months and cost very little.

Making Air Warnings Harder to Ignore

The AQI has become familiar in India over the past decade, even joked about by stand-up comics. But there’s little evidence that people or local authorities take its warnings seriously.

By including death risk, the AQHI could serve as a more effective tool. The aim is not to replace the AQI completely, but to enhance it so that people understand the real health consequences of the air they breathe.

Boxer Conor Benn Considered Taking His Own Life After His Doping Test Results

A known name in the boxing ring, and for pushing his limits, Conor Benn also had a point in his life where he considered giving up easier than doing it all over again, every single day. Professional boxing had taken a huge toll on his mental health.

It was in 2022, that he was twice tested positive for women's fertility drug Clomifene. This came after his planned fight with Chris Eubank Jr was cancelled. Even before a lengthy ban would have been implemented, he gave up his license under its threat, thought he did fight his case.

For 2 years, Conor Benn maintained his innocence to UK Anti-Doping (Ukad) and the British Boxing Board of Control (BBBofC), before his provisional suspension was finally lifted in 2024. The long ordeal took a serious toll on him, and Benn openly admitted it pushed him to a breaking point, even making him consider ending his life.

“It’s hurt me,” Benn said in an emotional interview on Piers Morgan: Uncensored. “I didn’t think I was going to make it through this period. I didn’t think I was going to make it through.”

Have Considered Taking My Own Life

When asked if he had seriously considered taking his own life, Conor Benn responded: “Yeah. Yeah, I’d say so, and it upsets me now because I don’t know how I got that low. I was in a really dark place.”

He described the emotional toll of being publicly vilified for something he insists he didn’t do. “I was shamed for something I hadn’t even done. It felt like I was on death row for a crime I didn’t commit.”

“If I had done something wrong, I’m human, I would’ve owned up to it,” he continued. “I’d say, ‘I made a mistake,’ and raise my hands. But not this. Never this.”

Reflecting on what he felt was an unjust situation, Benn said, “It felt like seven years of hard work, sacrifice, time away from my family, and everything I built was torn apart because of someone else’s incompetence. It’s been incredibly hard for my family.”

After finally being “cleared of any wrongdoing,” the welterweight boxer reaffirmed his long-held position: “I’ve always been an advocate for clean sport.”

In a statement shared on X, Benn called the past two years “unquestionably the toughest fight” of his life. “It’s been a rollercoaster period,” he wrote, “during which the WBC had already ruled I was innocent, and the NADP initially concluded there was no case to answer and I was free to fight.”

What Is Clomiphene?

As per the National Institute of Health's National Library of Medicine, US, clomiphene is a pharmacotherapeutic agent integral to the treatment of anovulatory or oligo-ovulatory infertility, plays a pivotal role in inducing ovulation for individuals aspiring to conceive.

This is usually used to treat infertility, especially in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). However, Clomifene can be used to boost testosterone levels in men, and is banned inside and outside competition by the World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada).

As per a 2019 study, titled, Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Testicular Axis Effects and Urinary Detection Following Clomiphene Administration in Males, Clomiphene citrate is also known to be abused by healthy athletes such as bodybuilders and weightlifters for performance enhancement because it raises serum testosterone and gonadotropin levels.

Adverse Effects

Some of the reported side effects of using clomiphene include headaches, dizziness, worsening of existing psychiatric conditions, gynecomastia (enlarged male breast tissue), testicular tumors, hot flashes, digestive issues, and breast pain. Other commonly observed reactions are nausea, vomiting, enlarged ovaries, blurred vision, visual disturbances like scintillating scotoma, abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic discomfort, and elevated triglyceride levels.

In more severe cases, clomiphene use has been linked to multiple pregnancies, low platelet count (thrombocytopenia), pancreatitis, liver damage, a possible increased risk of ovarian cancer with long-term use, a heightened risk of malignant melanoma, and serious visual impairments.

One of the more dangerous complications is ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), which has been reported in patients undergoing clomiphene citrate therapy for ovulation induction. OHSS can escalate rapidly, sometimes within 24 hours, and may become a medical emergency.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited