- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Could A ‘Harmless’ Virus Be Behind Parkinson’s? New Study Raises Big Questions

Credits: Canva

A virus long thought to be harmless might now play a key role in unraveling the mystery of Parkinson's disease. Human Pegivirus (HPgV), a virus that is normally found in blood and which was long believed to be harmless, has been found in patients diagnosed with Parkinson's disease in their brains. The research published on July 8 in JCI Insight has the potential to change scientists' understanding of the origin of the neurodegenerative disorder that strikes over 1 million Americans.

Guided by Dr. Igor Koralnik, Northwestern Medicine chief of neuroinfectious diseases and global neurology in Chicago, the study detected HPgV in 50% of Parkinson's patients' autopsied brains—but none in the control group. "We were surprised to detect it in the brains of Parkinson's patients at such high frequency and not in controls," Koralnik said.

HPgV, a member of the same virus family as hepatitis C, is usually symptomless and generally overlooked in clinical practice. Nevertheless, this new finding indicates that HPgV is possibly not as harmless as previously thought. The virus was found not only in the brains of infected patients but also in their spinal fluid—a sign that it has possibly infiltrated the central nervous system.

Perhaps more fascinating is how individuals' immune systems respond to HPgV. These responses, says Koralnik, were highly variable and influenced by genetic considerations. Specifically, individuals carrying the Parkinson's-linked LRRK2 gene mutation exhibited unique immune responses, implying a possible interaction between the virus and the body's genetic topology.

Parkinson's disease is mostly an idiopathic condition—i.e., most instances occur without a recognized genetic etiology. This has prompted researchers for many years to pursue environmental etiologies, such as toxin exposure and head injury. The potential viral link adds another twist to that theory. If HPgV is found to be causal, it would be one of the first known environmental factors directly implicated in Parkinson's disease development.

This implies it might be an environmental factor that acts on the body differently than we previously understood," said Koralnik. "It might affect how Parkinson's arises, particularly in individuals with specific genetically derived backgrounds."

Why HPgV Could Matter More Than We Thought?

The researchers autopsied the brains of 10 Parkinson's patients and matched them with 14 brains of healthy individuals. HPgV was found in half of the Parkinson's brains but none of the healthy brains. Further, scientists detected evidence of more damage to the brain in the virus-positive patients, which further solidified the connection.

They next examined blood samples from more than 1,000 people from the Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative, a large, ongoing study supported in part by the Michael J. Fox Foundation. Just 1% of those with detectable HPgV in their blood, which suggests that the virus can evade detection or pass into the brain without being detected using routine blood tests.

Parkinson's disease is marked by the death or damage of dopamine-producing neurons of the basal ganglia, which is a region of the brain that controls movement. When dopamine levels decline, symptoms such as trembling, stiffness, and poor coordination start to develop. But the disease also produces non-motor symptoms resulting from damage in other locations—such as fatigue, gastrointestinal problems, and blood pressure abnormalities.

How Parkinson's Usually Progresses in the Brain?

A characteristic of Parkinson's is the presence of Lewy bodies, aggregations of misfolded alpha-synuclein protein within brain cells. These deposits are thought to lead to cell death and loss of cognitive function.

The new study opens up the possibility that HPgV either directly injures neurons or provokes immune reactions that make alpha-synuclein aggregation worse. Both possibilities offer new leads for investigation, diagnosis, and ultimately treatment.

As Parkinson's advances, most patients develop cognitive symptoms ranging from mild forgetfulness and difficulty concentrating to frank Parkinson's dementia. This dementia is closely associated with Lewy body accumulation and progresses over time.

Stress, depression, and some drugs make cognitive symptoms more severe, so early detection and management are important. If HPgV is found to be affecting these changes in cognition, it would reveal the possibility of preventive interventions targeting viral suppression or immune modulation.

This research is just the start. Koralnik and his colleagues are now working on two main questions: how frequently does HPgV invade the brain, and how does its invasion relate to the severity of the disease? They're also exploring whether there are other viruses with such effects, particularly in people with genetic mutations such as LRRK2.

"We also want to know how genes and viruses communicate with each other; information that may uncover why Parkinson's starts and may inform the next generation of therapies," Koralnik said.

Future research might investigate whether antiviral treatments or vaccines could slow the development of Parkinson's in virus-positive individuals. Another option is the use of HPgV as an earlier disease biomarker or disease tracking.

This study highlights an overarching trend in medicine today: the reevaluation of microbes previously known to be innocuous. From the bacteria in our guts to the latent viruses in our systems, we are finding that these innocuous-looking commuters on our body highways have significant long-term impacts on health.

For families and patients with Parkinson's disease, this study provides a glimmer of hope—if not for a quick fix, then for better understanding and more individualized means of care.

As with so many scientific advances, the discoveries raise as many questions as they resolve but for a disease as multifaceted and life-changing as Parkinson's, even a step in the direction of shedding light on its causes is a leap of giant proportions toward future treatments.

There’s Urgent Need For RSV Immunisation In India As Virus Continuous To Claim Infant Lives, Says Top Pediatrician

Credits: Canva

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) might sound like a complicated medical term, but for millions of families across the globe, especially in India, it’s become a harsh and deadly reality. Though often mistaken for a seasonal cold, RSV is the leading cause of lower respiratory tract infections in children under five—and it’s killing thousands.

Each year, RSV is linked to approximately 3.6 million hospitalisations and nearly 100,000 deaths in children under five. India, with its annual birth cohort of over 25 million, contributes significantly to this global burden. In 2024 alone, 2,360 infant deaths in just three cities—Bengaluru, Kolkata, and Mumbai—were reported as RSV-related and experts believe this is only the tip of the iceberg.

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) is a highly contagious virus that infects the respiratory tract, particularly affecting the nose, throat, lungs, and breathing passages. It spreads through droplets from an infected person via coughing, sneezing, or even kissing. Contaminated surfaces like cribs, toys, or door handles can also carry the virus for hours.

RSV is so widespread that almost every child is infected by it at least once by the age of two. While it might look like a regular cold in some cases, in many infants, RSV progresses rapidly into bronchiolitis or pneumonia—both of which can be life-threatening.

Shockingly, around 80% of children under two who are hospitalised with RSV have no prior risk factors. Which means even full-term, healthy infants are at risk.

Why Is RSV So Underdiagnosed in India?

Despite being a notifiable disease in India for nearly five decades, RSV is severely under-tested. Dr. Vasant M. Khalatkar, National President of the IAP, pointed out that RSV testing in India often happens only when a full-blown outbreak occurs—like the one seen in Kolkata earlier this year.

“People still treat it as a bad cold,” Dr. Khalatkar said at a Bengaluru roundtable on RSV. “But for infants, RSV can escalate within three days from mild symptoms to severe respiratory complications that demand hospitalisation, oxygen support, or ventilation.”

A lack of awareness among caregivers and healthcare providers, combined with limited diagnostic access, has created a dangerous information gap—one that continues to cost young lives.

RSV Is the Leading Cause of Pediatric Respiratory Illness in India

Dr. Bhavesh Kotak, Head of Medical Affairs at Dr Reddy’s, underscored that RSV accounts for 63% of all acute respiratory infections in young children, citing WHO-backed data. In India, this means a significant share of childhood respiratory hospitalisations are linked to RSV, especially during monsoon and early winter months.

RSV doesn’t discriminate—children from all socio-economic backgrounds, including those born full-term, are frequently hospitalised. Unlike in high-income countries that have early preventive care and widespread immunisation, India still struggles with timely diagnosis and access to life-saving tools.

The most promising development in the fight against RSV is the introduction of long-acting monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and maternal vaccines—both backed by WHO and CDC guidelines.

Palivizumab, available for several years, has been used in high-risk infants but requires monthly doses throughout the RSV season.

Nirsevimab, a new and highly effective long-acting antibody, offers season-long protection with a single dose and is now being rolled out globally, including in India.

Additionally, the WHO recommends maternal vaccination with Abrysvo® during weeks 32–36 of pregnancy to protect babies after birth. This approach helps infants develop passive immunity and dramatically lowers their risk of severe RSV disease.

Dr. Khalatkar emphasised that immunisation—when paired with awareness and access—can significantly reduce RSV-related hospitalisations and deaths.

Is This Crisis Preventable?

Let’s break this down: India has 25 million newborns annually. Without preventive strategies, even a small percentage developing severe RSV means hundreds of thousands of hospitalisations and thousands of avoidable deaths. Unlike high-income countries, India faces several hurdles:

- Low RSV awareness among parents and healthcare providers

- Infrequent diagnostic testing

- Limited access to immunisation options

- Lack of inclusion of RSV immunisation in national programs

This gap is precisely where action is most needed.

Global Agencies Push for Immunisation

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), RSV is the leading cause of hospitalisation in U.S. children under one year. RSV also causes 100,000–160,000 hospitalisations annually in U.S. adults aged 60 and older. The CDC recommends:

- One-time RSV vaccination for adults 75+ and those aged 60–74 with chronic conditions

- Maternal RSV vaccine for pregnant women during the third trimester

- Nirsevimab injection for babies born during or just before RSV season (October to March)

If adopted effectively in India, similar immunisation protocols could transform RSV management—especially for the first 6 months of an infant’s life, when vulnerability is highest.

Simple precautions like handwashing, covering coughs, and disinfecting surfaces are useful but insufficient in high-burden, high-transmission environments—particularly for babies under 12 months. Experts unanimously agree that preventive immunisation is the game-changer.

WHO’s Dr. Kate O’Brien summed it up clearly: “The RSV immunisation products can transform the fight against severe RSV disease, dramatically reduce hospitalisations and deaths, and save many infant lives globally.”

RSV is no longer a vague acronym in pediatric medicine—it’s a clear and present danger to child health in India and worldwide. And while developed nations have made strides in RSV prevention, India remains at a critical crossroad.

Over 8 Million U.S. Teens Now Prediabetic, CDC Warns; Can This Health Crisis Be Reversed With Lifestyle Tweaks?

Credits: Freepik

The CDC has just delivered a reality check revealing over 8.4 million American teens aged 12 to 17—roughly one in three—are prediabetic. That’s 32.7% of U.S. adolescents showing early signs of blood sugar trouble that could spiral into full-blown type 2 diabetes. And this isn’t just about elevated glucose levels. This is a window into a much larger crisis: preventable chronic illness silently growing among kids who haven’t even finished high school.

“This is a wake-up call,” says Dr. Christopher Holliday, the CDC’s Director for Diabetes Translation, pointing to the massive and preventable health burden the country now faces. The warning is clear—teen health is declining, and unless there’s a nationwide shift in how we approach diet, movement, stress, and sleep, things are going to get worse before they get better.

Prediabetes means your blood sugar levels are elevated but not high enough for a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. It’s like standing at the edge of a cliff—you’re not falling yet, but you’re dangerously close.

During puberty, a teen’s body undergoes hormonal shifts that can naturally interfere with how well insulin works. According to Yale Medicine, this makes adolescence a critical window for diabetes risk to take root. Without intervention, prediabetes can evolve into type 2 diabetes, paving the way for serious health complications including kidney damage, stroke, and cardiovascular disease.

Type 2 diabetes itself is a long-term condition where the body struggles to use insulin properly. Over time, blood sugar builds up in the bloodstream and starts damaging tissues and organs. The progression is slow and mostly silent. Many don’t even know they’re prediabetic until symptoms become too obvious to ignore.

The CDC's 2023 data isn’t the first red flag. A 2020 study published in JAMA Pediatrics revealed that the prediabetes rate in teens more than doubled between 1999 and 2018—from 12% to 28%. The latest CDC estimate of 32.7% suggests that the trend hasn’t just continued—it’s accelerating.

What’s even more sobering is how unevenly this crisis affects different groups. Teens living in poverty are significantly more likely to be prediabetic, tied to issues like food insecurity, poor access to healthcare, and systemic inequality. Research from the University of Pittsburgh connects prediabetes risk with lack of insurance and household incomes below 130% of the federal poverty level.

And there’s a racial disparity too: African American, Hispanic/Latino, American Indian, Alaska Native, Pacific Islander, and some Asian American communities carry a disproportionately high burden of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes.

Is This Collision of Lifestyle and Access?

There’s no single culprit. But a combination of poor nutrition, sedentary habits, limited access to safe outdoor spaces, ultra-processed food marketing, and rising stress levels among adolescents are all playing a role.

Let’s be honest—the modern American teen lifestyle is working against metabolic health. Fast food is cheap and available everywhere. Physical education has been reduced or eliminated in many schools. Screen time has skyrocketed, especially since the pandemic. Many families, particularly those struggling financially, don’t have the luxury of prioritizing healthy eating or gym memberships.

Add to that a healthcare system that often fails to screen for prediabetes in young people, and you’ve got a perfect storm.

Can Lifestyle Tweaks Actually Reverse Prediabetes?

Yes—and this is where the good news comes in. According to the American Diabetes Association, prediabetes can be reversed or delayed through sustainable, everyday choices. Dr. Holliday emphasizes that “simple life changes—like healthy eating and staying active—can make a big difference.” Here’s what makes the biggest impact:

- Teens should be active at least three times a week—but ideally more. This doesn’t mean hours at the gym. Walking, biking, dancing, or playing a sport counts.

- Meals should center around whole foods—vegetables, fruits, whole grains—while cutting back on sugary beverages, red meats, and refined carbs.

- Even a 5–7% reduction in body weight in overweight individuals has been shown to significantly lower diabetes risk.

- Chronic stress raises cortisol, which can mess with blood sugar. Meanwhile, lack of sleep can interfere with insulin function. Most teens need 8–10 hours per night.

These aren’t drastic changes. In fact, experts say even modest shifts in habits can dramatically reduce risk.

Is This A Problem of Awareness and Urgency?

One of the most troubling aspects of prediabetes is how few people know they have it. Among American adults, more than 80% of those with prediabetes are unaware. And in teens, the lack of screening and routine checkups makes it even easier for warning signs to go unnoticed.

The key now is early intervention. Pediatricians, schools, and families need to be having these conversations. Blood sugar testing should be routine for at-risk teens. And public health efforts must prioritize communities most affected—those dealing with food deserts, high poverty rates, and systemic barriers to care.

What Needs to Change at a National Healthcare Level?

This isn’t just a family-level issue. It’s a national health crisis that demands systemic action. Here’s what needs to shift:

Healthcare policy: Expand routine screenings for teens, especially in underserved populations.

Food access programs: Subsidize fresh produce in low-income areas and restrict junk food marketing to kids.

School reforms: Reinstate physical education, revamp cafeteria offerings, and make mental health counseling widely available.

Community initiatives: Fund safe recreational spaces, after-school sports, and education campaigns targeting families and caregivers.

The fact that over 8 million U.S. teens are already prediabetic should stop us in our tracks but this isn’t a lost cause. Prediabetes doesn’t have to become diabetes. The road ahead doesn’t require miracles—just smarter choices, better systems, and the will to prioritize adolescent health. If the U.S. can treat this data as the urgent warning it is, we can flip the script on youth diabetes before it's too late.

Can AI Predict Your Risk Of Cancer? FDA Approved A New Tool That Spots Disease 5-Year Before It Appears

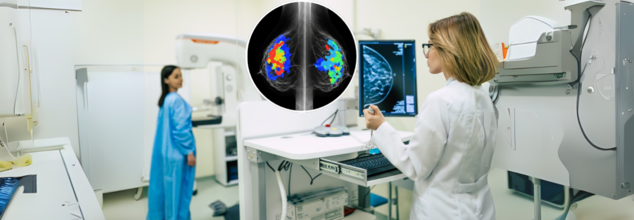

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authorized the first-ever artificial intelligence (AI) tool designed to predict a woman’s five-year risk of breast cancer using a routine screening mammogram. The announcement, made on May 30, 2025by the tool’s developer, Clairity, marks a pivotal step in how breast cancer is detected and prevented—and it may just redefine the standard of care in women’s health.

This isn’t just another AI detection tool. Clairity’s platform, known as CLAIRITY BREAST, is not focused on spotting existing tumors, but rather on forecasting who may develop breast cancer years in advance. It shifts the paradigm from early detection to early risk prediction, potentially giving clinicians a critical head start in identifying high-risk individuals—before cancer ever forms.

This innovation comes from the vision of Dr. Connie Lehman, a radiologist and professor at Harvard Medical School, and the former chief of breast imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital. With decades of experience detecting cancers on mammograms, Lehman realized a key gap in screening: the lack of modern, image-based risk assessment tools.

“Our imaging technology was advancing fast, but our methods to identify women at high risk weren’t keeping up,” said Lehman at the 2025 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Meeting, where the FDA authorization was announced.

While most existing risk models consider age, genetics, and family history, they often miss women who don’t fit those boxes. In fact, 85% of women diagnosed with breast cancer have no family history, and 50% have no identifiable risk factors at all. This makes Clairity’s approach uniquely valuable.

How The Breast Cancer Detection AI Tool Works?

CLAIRITY BREAST leverages deep learning and computer vision algorithms trained on millions of mammogram images, each linked to five-year follow-up data. By analyzing the subtle imaging features in breast tissue—often imperceptible to the human eye—the system generates a validated five-year risk score for each patient.

That score is integrated seamlessly into existing clinical workflows, providing radiologists and oncologists with a powerful new layer of information for decision-making.

“Now we can move even further upstream,” said Lehman. “Not just detecting cancer early—but predicting it, personalizing care, and even preventing it.”

Traditional screening strategies are reactive, catching cancer once it’s already present. But with Clairity, the approach becomes proactive, especially for women who may otherwise fall through the cracks of conventional risk models.

“This FDA authorization is a turning point,” said Dr. Larry Norton, founding scientific director at the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. “Most existing risk models miss the very women who go on to develop breast cancer. Clairity changes that.”

Younger women in particular stand to benefit. While breast cancer incidence is still highest in women over 50, cases among younger women are rising, yet they’re often not recommended for routine screening unless they have known risk factors. Clairity’s AI-powered insights can help clinicians tailor screening plans and intervene earlier for women who previously would have gone unflagged.

Dr. Lehman describes breast cancer not as a binary—either present or not—but as a continuum, with progression that begins long before a tumor is visible.

“There’s a point even before ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), when cancer hasn’t developed, but the risk is there,” she explained. “That’s where CLAIRITY can intervene—well before invasive cancer begins.”

The goal, according to Lehman, isn’t just to detect breast cancer earlier, but to predict and prevent it, in the same way that doctors routinely assess cardiovascular risk based on blood pressure, cholesterol, or BMI.

Until now, breast cancer lacked such a dynamic, image-based risk tool. That’s what makes Clairity’s authorization so significant.

AI’s Expanding Role in Radiology

AI has been used in radiology for decades, first to flag microcalcifications in mammograms in the early '90s. But back then, AI systems were limited to rule-based logic and needed exhaustive human guidance.

Today’s AI, especially in platforms like Clairity, goes far beyond what human vision can perceive. It identifies patterns in breast tissue texture and density at the pixel level, learning from vast image sets without needing explicit human-labeled inputs.

Lehman compared it to how machines learn to distinguish cats from dogs—by exposure to thousands of examples rather than being told what features to look for. In the case of breast cancer, the stakes are obviously much higher.

“This technology allows us to see what we couldn’t see before, and that opens doors to dynamic risk assessment,” Lehman said. “Eventually, we may even use these tools to monitor how interventions like medication, weight loss, or hormone therapy change a woman’s risk over time.”

Backed by Santé Ventures and ACE Global Venture, Clairity was founded in 2020 with a clear goal: to bring sophisticated AI tools to routine mammography. Now, with FDA de novo authorization, it’s set to hit the market by late 2025.

The company estimates the global market for breast cancer prediction tools at $63 billion, suggesting broad clinical interest and commercial potential.

As imaging centers, hospitals, and oncologists look to integrate risk prediction into daily care, Clairity's success will depend on adoption, clinician trust, and real-world outcomes. But with this regulatory milestone, a major hurdle has been cleared.

The FDA’s green light for CLAIRITY BREAST doesn’t just add a new tool to the cancer detection toolbox—it fundamentally changes the playing field. By enabling risk prediction from a single mammogram, it turns routine screening into a forward-looking, personalized roadmap for prevention.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited