- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Could COVID-19 Help Fight Cancer? A Groundbreaking Study Finds Out the Link

The COVID-19 pandemic was a traumatic experience for most, claiming countless lives and forcing many to suffer in isolation. The fear and disruption caused by the virus during 2020-2021 extended beyond the pandemic itself, affecting the diagnosis and treatment of other life-threatening diseases like cancer and tuberculosis. However, what if we told you that the very virus that upended our lives might hold the key to fighting cancer?

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. During the pandemic, some doctors noticed something intriguing: cancer patients who contracted COVID-19 experienced tumor shrinkage or reduced growth. Initially, it was unclear if this was a coincidence or if there was a deeper connection.

A recent study led by researchers at the Northwestern Medicine Canning Thoracic Institute, published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation last month, sheds light on this phenomenon. This groundbreaking research could pave the way for new treatments to combat cancer, especially metastasis—the process by which cancer spreads to different parts of the body.

Dr. Ankit Bharat, chief of thoracic surgery at Northwestern University, and his team found that the SARS-CoV-2 virus influences a type of immune cell in the body called monocytes. Normally, cancer cells manipulate monocytes to shield themselves from the immune system's attack. However, the researchers discovered that the presence of the COVID-19 virus alters this behavior.

The viral RNA appears to transform monocytes into a rare type of immune cell, scientifically termed inducible nonclassical monocytes. These transformed cells can be enhanced with specific drugs to infiltrate tumors and metastatic regions. Once inside, they break down the cancer’s protective shield, enabling the body’s immune system to identify and attack the cancer cells more effectively.

This is a significant breakthrough, particularly for tackling cancer metastasis, which remains a major challenge in cancer treatment. Inside the tumors, these transformed monocytes trigger the production of natural killer cells—specialized immune cells that directly destroy cancer. The study has already shown promising results in mouse models for cancers such as melanoma, breast, and colon cancer.

The findings offer hope for innovative treatments and underscore the unexpected ways in which the virus could contribute to medical advancements. While the COVID-19 pandemic left a trail of devastation, its complex interactions with the human body might open new doors in the fight against cancer.

The COVID-19 pandemic shook the entire world, changing lives, economies, and healthcare systems. While it brought immense suffering, studies like this remind us of the hidden potential for breakthroughs through adversity. Cancer, one of the most deadly diseases affecting people across all age groups, continues to devastate lives without discrimination. This research not only unveils a fascinating connection between SARS-CoV-2 and cancer but also marks the beginning of a new hope. If utilised effectively, these findings could lead to revolutionary treatments, offering hope in the relentless fight against a disease that knows no boundaries.

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: Nurse Who Recovered Dies Of Cardiac Arrest

Credits: Canva

Nipah virus Outbreak In India: After two cases of Nipah virus were confirmed in Kolkata, one of the nurses who has recovered from Nipah virus died of a cardiac arrest. Health and Me previously reported on the male nurse being discharged.

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: What Happened With The Nurse?

The 25-year-old nurse who recovered from Nipah virus infection died of cardiac arrest on Thursday. As per the official statement given to news agency PTI, "She died of cardiac arrest this afternoon. Though she had recovered from Nipah infection, she was suffering from multiple complications."

The reports show that she also developed a lung infection and contracted a hospital-acquired infection during treatment. The official said, "She was trying to regain consciousness, move her limbs, and speak before her condition suddenly deteriorated. She died at around 4.20pm."

The nurse fell ill in early January after returning home on December 31 for the New Year holidays and was initially admitted to Burdwan Medical College and Hospital before being shifted to the private hospital in Barasat.

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: What Is Nipah Virus?

As per the World Health Organization (WHO), Nipah virus infection is a zoonotic illness that is transmitted to people from animals, and can also be transmitted through contaminated food or directly from person to person.

In infected people, it causes a range of illnesses from asymptomatic (subclinical) infection to acute respiratory illness and fatal encephalitis. The virus can also cause severe disease in animals such as pigs, resulting in significant economic losses for farmers.

Although Nipah virus has caused only a few known outbreaks in Asia, it infects a wide range of animals and causes severe disease and death in people.

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: What Are The Common Symptoms?

- Fever

- Headache

- Breathing difficulties

- Cough and sore throat

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Muscle pain and severe weakness

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: What Are Experts Saying?

Dr Krutika Kupalli, a Texas-based expert who formerly also worked with the World Health Organization (WHO), told The Daily Mail that the possibility of Nipah virus outbreak is 'absolutely' something the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) should be 'closely monitoring'.

Read: Experts Reveal Risks Of Nipah Virus Outbreak In The US, CDC On Alert

“Nipah virus is a high-consequence pathogen, and even small, apparently contained outbreaks warrant careful surveillance, information sharing, and preparedness. Outbreaks like this also underscore the importance of strong relationships with global partners, particularly the WHO, [which] plays a central role in coordinating outbreak response and sharing timely, on-the-ground information," she said.

A CDC spokesperson told The Daily Mail that the agency is in 'close contact' with authorities in India. "CDC is monitoring the situation and stands ready to assist as needed."

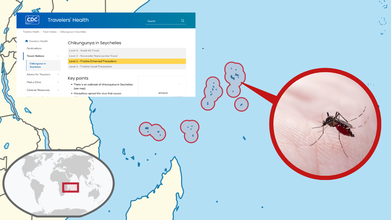

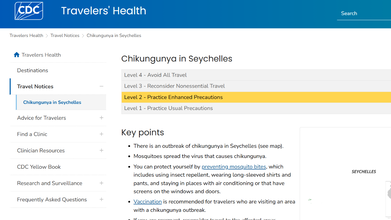

CDC Travel Advisory Issued For These Islands Amid Chikungunya Outbreak

Credits: CDC and Canva

CDC Travel Advisory: The US has warned travelers to be careful if they plan to visit the Seychelles islands anytime soon. The island is located in northeast of Madagascar and is known for its secluded beaches. As per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a 'Level 2' advisory for the island has been issued and travelers have been asked to 'practice enhanced precautions' if they do plan to visit.

CDC Travel Advisory: Why Did US Issue Health Warning?

The warning has been issue in response to an outbreak of chikungunya, which is a viral disease that could spread to humans by mosquitoes.

A Level 2 travel advisory has been issued, which means the travelers are expected to practice enhanced precautions as compared to a Level 1 advisory that only asks travelers to practice usual precautions.

In more serious cases, Level 3 advisory is issued that asks travelers to reconsider non-essential travel, whereas a Level 4 advisory asks travelers to avoid all travel.

Read: Chikungunya Spreads Across Tamil Nadu: All You Need To Know

CDC Travel Advisory: What Is Level 2 Health Warning?

As CDC issues travel advisory, here is what travelers are expected to do:

- Travelers are expected to protect themselves by preventing mosquito bites, which includes using insect repellent, wearing long-sleeved shirts and pants, and staying in places where air conditioning or that have screens on the windows and doors

- The CDC also tells travelers to get vaccinated for those who are visiting the area affected by a chikungunya outbreak

- If a traveler is pregnant, they are asked to reconsider travel to affected area, especially if they are closed to delivering their baby. Mothers infected around the time of delivery can pass the virus to their baby before or during delivery. Newborns infected in this way or by a mosquito bite are at risk for severe illness, including poor long-term outcomes

- If someone has a fever, joint pain, headache, muscle pain, joint swelling, or rash during or after the travel, they must seek medical care

CDC Travel Advisory: Which Other Places Got The Chikungunya Level 2 Notice

From September 26, 2025 to February 11, 2026, the CDC issued travel advisory against five places for Chikungunya, which includes:

- Bolivia: There is an outbreak of chikungunya in Santa Cruz and Cochabamba Departments

- Seychelles: Notice details mentioned above

- Suriname

- Sri Lanka

- Cuba

CDC Travel Advisory: What Is Chikungunya?

This is a disease that is transmitted from mosquitoes to humans and affects many people in the world. Found in densely populated countries and continents, like Africa, Asia and the tropics of the Americas, this has severe symptoms. This viral disease is caused by the Chikungunya virus of the Togaviridae.

First identified in the United Republic of Tanzania in 1952 and subsequently in other countries like Africa and Asia. Since 2004 the outbreak of CHIKV virus has become more widespread and caused partly due to the viral adaptations allowing the virus to be spread more easily by Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. The transmission has been noted to persist in countries where there is a large population, but interestingly, the transmission has been interrupted on islands where a high proportion of the population is infected and then immune.

CDC Travel Advisory: Symptoms of Chikungunya

The onset of the disease is usually in 4-8 days and after a bite of an infected mosquitoes, it is characterized by an abrupt onset of fever and then joint pain. This joint pain is severed and lasts for a few days but may prolong for months maybe even years. Other signs are joint swelling, muscle pains, headache, nausea, fatigue and rash.

Bacteria Found in Amul Milk Pouches, Officials Urge Pasteurization

In a now viral video from Trustified, an independent testing platform, food testers claim that Amul Taaza and Gold milk pouches contain coliform bacteria levels 98 times higher than FSSAI’s prescribed limits.

Additionally, Mother Dairy and Country Delight milk pouches showed total plate count levels far above safe thresholds. Total plate count (TPC), also known as Aerobic plate count (APC), measures viable microbial contamination, with lower levels indicating better quality.

Last month, the agency also claimed that the Amul Masti Dahi sold in pouches showed high coliform bacteria, yeast and mold, while tetrapack milk and dahi sold in cups passed quality checks.

However, Amul has aggressively dismissed these allegations, citing them to be fear-mongering and noting that all of its products meet safety standards. Instead of manufacturing failure, the company has pointed to possible breaks in the cold chain at the retail or distribution level.

What Is Coliform Bacteria?

According to ScienceDirect.com, coliform bacteria are rod-shaped, gram-negative bacteria that do not form spores. They may or may not be able to move and they can break down lactose to produce acid and gas when grown at 35–37°C.

E. coli is a specific type of coliform bacteria that lives in the intestines of humans and animals and can cause infections in your gut, urinary tract and other parts of your body.

Coliform bacteria typically doesn't cause serious illness but if high amounts of coliform bacteria are found, it suggests that harmful germs from feces, like bacteria, viruses or parasites, may also be present.

Certain strains of coliform bacteria can make you sick with watery diarrhea, vomiting and a fever, according to Cleveland Clinic.

In many Indian milking setups, milk is extracted by hand and there is a high possibility that cows' udders are not being cleaned thoroughly before extracting milk from them, making it easy for bacteria in the cow dung to contaminate milk.

Why Is Milk Pasteurization Necessary?

Developed by Louis Pasteur in the 19th century, pasteurization is a critical food safety process that involves heating liquids, most commonly milk but also juice, eggs and beer, to a specific temperature for a set period to destroy harmful bacteria, viruses, and pathogens including E. coli, Campylobacter, Listeria, and Salmonella.

This process significantly reduces the risk of foodborne illnesses such as typhoid, tuberculosis, and listeriosis without significantly altering the nutritional value or taste of the product.

In most milk processing plants, chilled raw milk is heated by passing it between heated stainless-steel plates until it reaches 161 degrees Fahrenheit. It’s then held at that temperature for at least 15 seconds before it’s quickly cooled back to its original temperature of 39 degrees.

Pasteurization is essential for children, pregnant women and the immunocompromised, as it prevents infections that can cause severe complications, including miscarriage or death.

Unlike sterilization, pasteurization does not destroy all microorganisms, which is why pasteurized milk must be kept refrigerated.

John Lucey, a food science professor at University of Wisconsin-Madison, notes: "Pasteurization is an absolutely critical control point for making dairy products safe. There really isn’t another single aspect that is as important as it is. If there is a pathogen or anything in the milk that we don’t want, pasteurization destroys it. It is our industry’s shield."

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited