- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Could These Common Cancer Drugs Could Be The Key To Reversing And Treating Alzheimer’s?

Credits: Canva

Alzheimer’s has long been one of medicine’s most frustrating puzzles. Despite decades of research and billions in funding, we still don’t have a cure, and the handful of approved treatments offer only modest relief. But now, scientists from UC San Francisco and the Gladstone Institutes may have uncovered an unlikely lead: two cancer drugs that could potentially reverse Alzheimer’s-related brain changes.

The findings, published in the journal Cell, are generating buzz for one big reason: they didn’t come from years of trial-and-error drug development, but from a computational deep dive into big data, gene expression, and real-world patient records. The research team didn’t set out to find a miracle—yet what they discovered might just change the way we treat one of the world’s most devastating neurological diseases.

To understand how this started, let’s zoom in on what actually happens in the Alzheimer’s brain.

In people with the disease, neurons and glial cells undergo dramatic shifts in gene expression—the biological instructions that tell a cell how to function. These changes disrupt memory, cognition, and eventually basic bodily functions.

Instead of targeting a single protein (like beta-amyloid plaques, the long-standing focus in Alzheimer’s research), UCSF scientists took a broader approach. They analyzed single-cell gene expression data from brain tissue donated by individuals with and without Alzheimer’s. This allowed them to pinpoint the exact genetic changes happening in both neurons and glia during disease progression.

Then came the twist: they used a database known as the Connectivity Map—essentially a chemical encyclopedia—to match those Alzheimer’s gene expression patterns against thousands of existing drugs. The goal? To find drugs that reverse those patterns.

Out of 1,300 drugs studied, 86 had the potential to reverse Alzheimer’s-associated gene changes in at least one brain cell type. Only 25 affected multiple cell types. And of those, just 10 were already FDA-approved.

That’s how two unexpected candidates—letrozole (a breast cancer drug) and irinotecan (used for colon and lung cancers)—emerged as frontrunners.

The team didn’t stop at computer modeling. They turned to electronic health records, combing through anonymized data from 1.4 million patients over the age of 65 in the UC Health Data Warehouse.

What they found was striking: patients treated with letrozole or irinotecan had lower rates of Alzheimer’s. This wasn’t a controlled trial, but it was a strong signal—and one worth testing further.

So the team brought the drugs into the lab, using mice genetically engineered to develop Alzheimer’s-like symptoms. As the mice aged and memory declined, the researchers treated them with each drug, individually and in combination.

The drug combo not only reversed the abnormal gene expression signatures—it also reduced brain degeneration, lowered toxic protein buildup, and restored memory in the mice.

“It’s incredibly encouraging to see the validation of computational predictions in a rigorous animal model,” said Dr. Yadong Huang, senior investigator at Gladstone and co-senior author of the study. “This points toward a real path forward.”

Why Repurposing Drugs Is a Game-Changer?

Developing new drugs from scratch is notoriously slow, risky, and expensive. On average, it takes over a decade and billions of dollars to bring a new drug to market. Alzheimer’s drugs, in particular, have a poor track record. Many promising candidates have failed in late-stage trials, often because they target a single mechanism in a disease that’s anything but simple.

Repurposing existing drugs changes that calculus. “These are already FDA-approved,” said Dr. Marina Sirota, co-senior author and interim director of UCSF’s Bakar Computational Health Sciences Institute. “We’re not starting from zero. We know their safety profiles, which speeds up the timeline dramatically.”

Instead of 10 years, researchers believe this approach could move into clinical trials within two or three.

How Might These Cancer Drugs Work Against Alzheimer’s?

It’s still early, but there are theories. Letrozole is known to suppress estrogen, a hormone that regulates a wide network of genes, including those involved in cognition and brain metabolism. Estrogen suppression might realign gene expression in neurons affected by Alzheimer’s.

Irinotecan, on the other hand, may dampen inflammation by limiting the proliferation of glial cells. In Alzheimer’s, glia often overreact, causing harmful inflammation that contributes to neurodegeneration.

Other hypotheses suggest these drugs may improve how brain cells use energy—a process that often breaks down in neurodegenerative diseases.

Still, researchers caution that what works in mice doesn’t always translate to humans.

What About the Side Effects?

This is where the optimism meets reality. Both letrozole and irinotecan come with known and serious side effects. Letrozole can cause hot flashes, joint pain, and fatigue. Irinotecan’s side effects can include severe diarrhea, nausea, and immune suppression.

“These are potent medications designed to fight cancer,” Dr. Huang noted. “We’ll need to carefully assess whether their risks are acceptable for Alzheimer’s patients, especially in earlier stages of the disease.”

There’s also the question of dosage. Researchers may be able to use lower, safer doses when the drugs are repurposed—something future clinical trials will explore.

So, what’s next? The team is already planning a clinical trial to test the drug combination in people with Alzheimer’s. If successful, this would be the first time a repurposed cancer therapy was proven to meaningfully reverse cognitive decline in humans.

But even if these drugs don’t turn out to be the answer, the methodology could be.

“This is a new way of looking at neurodegenerative disease,” said Dr. Sirota. “Instead of going after one broken part, we’re looking at the whole system—and using big data to identify tools that are already in our toolbox.”

It’s too early to call this a cure. But in a field desperate for fresh approaches, this study offers something rare: real hope.

Alzheimer’s has resisted every easy fix. But by turning to unexpected sources—like cancer drugs—and using advanced data analysis, researchers may have found a new way forward. It’s not a silver bullet, and it won’t be without challenges. But this is one of the most promising leads in years—and it might just mark the beginning of a new chapter in Alzheimer’s treatment.

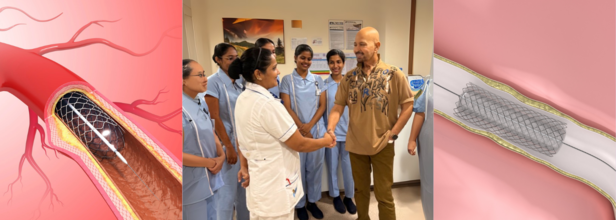

Rakesh Roshan Undergoes Angioplasty, Shares Health Update And Asks People Over 40 To Get Regular CT Scan

Credits: Canva and Instagram

Veteran filmmaker Rakesh Roshan, known for hits like Kaho Naa... Pyaar Hai and Krrish, opened up on Tuesday about his recent health scare that led to an urgent angioplasty procedure.

In a heartfelt Instagram post, the 74-year-old shared a photo from his hospital room, shaking hands with a nurse and thanking the medical team who cared for him.

While the photo appeared reassuring, his caption revealed a critical diagnosis that had, until recently, gone unnoticed.

Why Routine Checkups Are Important

Roshan wrote that during a routine full-body check-up, a cardiologist recommended a sonography of the neck. This suggestion proved to be a turning point. “By chance, we found out that although asymptomatic, both my carotid arteries to the brain were above 75% blocked,” he shared. “Which, if ignored, could be potentially dangerous.”

Without any outward symptoms, the condition could have led to a stroke or other serious complications. He immediately checked into the hospital to undergo “preventative procedures,” including angioplasty.

Now safely back home, Roshan says he feels well and is eager to resume his workouts. “I hope this inspires others to stay on top of their health, especially where the heart and brain is concerned,” he wrote.

A Reminder for Preventive Care Over Cure

The filmmaker urged everyone over the age of 45–50 to consider a CT scan for the heart and a carotid artery sonography as part of their annual health screenings. These tests, often overlooked, can detect hidden arterial blockages that may not present symptoms until it’s too late.

“I think it’s important to remember that prevention is always better than cure. I wish a healthy and aware year to you all,” he added.

His message was met with an outpouring of support from friends and well-wishers across the industry. Actors, including Anil Kapoor, Suniel Shetty, Tiger Shroff, and others left supportive comments and emojis. Roshan’s daughter Sunaina had also earlier confirmed to the media that her father had undergone an angioplasty “in his neck” and assured fans that he was “perfectly fine.”

What Is Angioplasty?

According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, angioplasty is a medical procedure used to restore blood flow through narrowed or blocked arteries. It is most commonly done to treat coronary artery disease but can also be used in other parts of the body, such as the carotid arteries leading to the brain.

The procedure involves inserting a thin, flexible tube called a catheter into a blood vessel. The catheter is guided to the blocked area, where a small balloon is inflated to compress plaque against the artery wall, thus opening the vessel and improving blood flow. In some cases, an atherectomy may also be performed to shave or remove the plaque.

The Role of Stents in Preventing Re-Narrowing

In nearly all modern angioplasty procedures, a stent is inserted to help keep the artery open. A stent is a tiny, mesh-like metal coil that is expanded at the site of blockage. Once placed, it prevents the artery from narrowing again.

There are two types of stents:

- Drug-eluting stents, which release medication to prevent scar tissue buildup

- Bare metal stents, which don’t have a drug coating but are used in patients who may be at higher risk of bleeding

Post-procedure, patients are typically prescribed antiplatelet medications to reduce the risk of blood clots and to ensure the stent remains open.

Risks and Follow-Up Care

While angioplasty is a relatively safe procedure, there can be complications if the stent becomes blocked or scar tissue develops. Some patients may require a repeat procedure or even radiation therapy (brachytherapy) to clear the narrowing.

That’s why ongoing medical supervision and lifestyle changes—such as regular exercise, a balanced diet, and avoiding tobacco—are key to long-term heart and brain health.

Federal Investigation Uncovers Failures in Organ Donation Protocols, Triggers National Reforms

Credits: Canva

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has announced a major overhaul of the nation’s organ transplant system, following a disturbing federal investigation that revealed serious ethical and safety concerns. At the heart of the issue is a Kentucky-based organ procurement organization (OPO), which allegedly continued preparations for organ donation in patients who showed signs of life.

The revelations have triggered swift action from federal agencies, as lawmakers call for transparency, stronger safeguards, and a renewed effort to rebuild public trust in the transplant process.

Uncovering a Troubling Pattern

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), under HHS, reviewed 351 authorized but incomplete organ donation cases linked to the Kentucky OPO that also serves Southwest Ohio and parts of West Virginia. Investigators found troubling practices in at least 103 of those cases, including patients displaying neurological signs incompatible with organ donation and concerns that some may not have been fully deceased at the time organ procurement was initiated.

Additional issues uncovered included poor neurological assessments, lack of coordination with medical teams, questionable consent processes, and misclassification of causes of death, especially in drug overdose cases. Smaller and rural hospitals were found to be especially vulnerable due to inconsistent oversight and limited resources.

Reopening a Closed Case and Demanding Accountability

The HRSA has now directed the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) to reopen a previously closed case that had been dismissed by the OPTN Board of Directors. The earlier review had claimed "no major concerns" in the case of a neurologically injured patient. However, the new independent investigation contradicted that conclusion and cited potential negligence.

The Kentucky OPO is now required to conduct a thorough root cause analysis, especially focusing on failures like not observing the required five-minute wait after cardiac death before beginning organ recovery. The organization must also implement stricter donor eligibility rules and establish a clear, formal procedure that allows any hospital or OPO staff member to halt the donation process if patient safety is at risk.

HRSA warned that the OPO will face decertification if it fails to comply with these corrective measures.

A Call for Reform and Reassurance

During a congressional hearing this week, Rep. Brett Guthrie of Kentucky, whose own mother died while awaiting a liver transplant, stressed the importance of restoring public confidence in the system.

“We have to get this right,” Guthrie said. “Hopefully people will walk away today knowing we need to address issues but still confident that they can give life.” He reaffirmed his commitment to remain a registered organ donor.

Lawmakers emphasized that while most organ donations are conducted safely and ethically, the near-misses uncovered by the investigation are deeply concerning and could deter future donors. Some families have already chosen to opt out of organ donor registries after these incidents were made public.

How Organ Donation Works in the U.S.

Organ donation in the U.S. is a complex process involving multiple entities. Hospitals are responsible for caring for critically ill or brain-dead patients. Once death is declared or life support is withdrawn, hospitals notify local OPOs, which coordinate the recovery and placement of organs with transplant centers.

While most donations occur after brain death, a growing number take place after circulatory death, when the heart stops following withdrawal of life support. In these cases, organs are only viable if death occurs quickly and is confirmed with a mandatory five-minute waiting period.

OPOs are not allowed to be involved in declaring death or the decision to end life support. However, recent reports suggest a blurred line in practice, with concerns that OPOs have pressured hospitals during end-of-life decisions.

Stronger Safeguards, Greater Transparency

As part of its response, HRSA has ordered the OPTN to strengthen national safeguards and mandate reporting of any instance where donation is paused due to concerns from families, hospital staff, or OPO teams. The aim is to create a culture where patient eligibility is continually reassessed and where concerns can be raised without fear.

In Kentucky, the OPO says it has already begun implementing changes. Staff at every partnering hospital are now given checklists outlining protocols for identifying and handling potential donors. A new system has also been set up to allow anonymous reporting of any concerns.

Barry Massa, head of Kentucky’s Network for Hope, emphasized that OPOs do not participate in life support decisions and are “not even in the room” when such determinations are made. Still, HRSA insists that the transplant network needs more proactive collaboration and clearly defined boundaries to protect vulnerable patients.

With over 100,000 people waiting for life-saving organ transplants in the U.S., federal officials say that reforming the system is not just necessary, it’s urgent.

Contagious Measles Virus Found In Austin Wastewater; How Water Could Accelerate The Outbreak?

Credits: Canva

Public health officials in Austin, Texas, have confirmed the detection of the measles virus in the city's wastewater, a discovery that has raised serious concerns about undiagnosed infections and vaccination gaps. The virus was detected during routine wastewater surveillance in Travis County during the first week of July. The findings were confirmed and made public by Austin Public Health (APH) on July 18.

This method of detection—sampling wastewater to trace pathogens before clinical cases emerge—is becoming an essential early-warning tool for tracking outbreaks. While no community-wide outbreak has been confirmed in Austin yet, experts warn that the presence of measles in wastewater is an unmistakable sign of silent transmission.

Measles is one of the most contagious viruses known. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), it can linger in the air for up to two hours after an infected person leaves a space. Just walking into a room where someone with measles once stood can be enough to contract the virus—especially if you're not vaccinated.

Despite being declared eliminated from the U.S. in 2000, measles has re-emerged in pockets, often brought in by unvaccinated international travelers. The virus then finds its way into vulnerable communities with low vaccine coverage, quickly spiraling into outbreaks.

Wastewater surveillance has previously been used to detect poliovirus, COVID-19, and norovirus before cases start showing up in clinics. It acts like a collective health snapshot of a community. When a virus like measles shows up in these samples, it’s often a red flag indicating undiagnosed or underreported cases.

Two confirmed measles cases have been reported in Travis County in 2024, both linked to travel. No outbreak has been officially declared yet in the region. The wastewater sample that tested positive was collected in the first week of July.

Similar detections in Utah, New Mexico, and California earlier this year were later followed by confirmed infections.

Meanwhile, a measles outbreak continues in southwestern Kansas, where the health department recently confirmed its 90th case, highlighting how rapidly the virus can spread once introduced into an underprotected community.

Why Measles Is Still a Threat in the US?

Despite elimination status, measles remains a global traveler. Its return to U.S. communities is almost always tied to:

- Unvaccinated individuals

- International travel

- Breaks in vaccine coverage

Once it re-enters a community, measles spreads like wildfire among the unvaccinated. Children under five, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals are especially vulnerable.

Dr. Desmar Walkes, Austin-Travis County Health Authority, made it clear: the only way to avoid an outbreak is through vaccination.

“This is just another important reminder on why we all need to get vaccinated against measles,” Walkes said in a statement. “Getting vaccinated helps to keep you, your family, and your friends safe from disease.”

Two doses of the MMR vaccine (measles, mumps, and rubella) are required for full protection. The first is typically given at 12-15 months, with a second dose at 4-6 years.

Vaccination is widely available through doctors’ offices and pharmacies, although children under 14 need a prescription to receive it at a pharmacy in Texas. For uninsured or underinsured residents, APH provides the MMR vaccine through its "Shots for Tots and Big Shots" clinics.

Why Detecting Measles in Wastewater Is a Serious Warning?

Measles appearing in wastewater isn’t just a scientific curiosity—it’s a serious public health signal. It suggests the virus could be silently spreading among people who are asymptomatic or haven’t yet developed clear symptoms. Because those with mild or early signs might not seek medical attention, many cases could go unreported and undiagnosed. This quiet transmission is dangerous—especially in areas with low vaccination rates—because even a single undetected case can trigger dozens of new infections within days. If public health systems don’t act quickly, these wastewater detections can shift from being early warning signs to precursors of a full-blown outbreak.

Austin’s situation isn’t isolated. The positive wastewater signal in Provo, Utah, earlier this month followed similar reports in New Mexico and California. In those instances, confirmed clinical cases were detected within weeks of the wastewater alert.

This pattern suggests that measles surveillance via wastewater may be a key tool in pandemic-era preparedness strategies—but only if paired with rapid vaccine action and public awareness. If you live in or near Austin-Travis County, here’s what health officials want you to know:

- Check your vaccination status. If you’re unsure, contact your healthcare provider.

- Make sure your children are fully vaccinated—especially before the school year begins.

- Don’t dismiss symptoms like fever, cough, or rash, particularly if you’ve been traveling.

- Stay informed through official health advisories, and avoid misinformation.

The presence of the measles virus in Austin’s wastewater should serve as a wake-up call. It’s not time to panic—but it is time to act. Vaccination remains our best defense against a disease that, while once thought eliminated, is still lurking in the background—waiting for its next opportunity to strike.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited