- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Diarrhoea Outbreak In Odisha Kills Two And Over 140 Hospitalised; Is It A Monsoon Menace Or Public Negligence?

Credits: Canva

A diarrhoea outbreak hit Ganjam district's Ustapalli village in Odisha, India, killing two individuals and hospitalizing more than 140. The outbreak was initially reported from Digapahandi block over the weekend. In a span of only three days, local hospitals were overwhelmed by patients with symptoms such as acute dehydration, severe stomach cramps, and vomiting.

There are ten patients in critical condition who have been shifted to MKCG Medical College and Hospital in Berhampur for intensive care. While medical personnel are deployed on the ground actively, the root cause is still being investigated. Preliminary suspicion is for contaminated drinking water, with test results on samples taken shortly.

“We’ve collected water samples from the village and are awaiting test results,” a medical officer told local reporters. “Meanwhile, awareness drives on hygiene and safe water consumption have been launched.”

This is not an isolated incident. Just weeks earlier, eight districts across Odisha, including Jajpur and Balasore, experienced widespread diarrhoea and cholera outbreaks. That previous wave of infections claimed at least 15 lives and affected over 1,500 individuals.

The Central team sent to Odisha validated the cause of the crisis: microbial contamination of water sources. Laboratory tests revealed several samples positive for E. coli and Vibrio cholerae — the cholera-causing bacterium. Significantly, 16 of 37 faecal samples from Jajpur were found positive for V. cholerae.

In recent cases, suspicion has also been cast on locally bottled drinking water consumed during public feasts in communities. Such small-scale bottlers frequently slip through food safety inspections, yet their products are widely distributed during public festivals.

How Can Diarrhoea Become Deadly?

On the surface, diarrhoea appears almost trivial — a symptom so easily treated with rest and fluids that it will go away on its own. But when it occurs in resource-poor areas or during outbreaks, this ubiquitous symptom can swiftly be deadly.

What is most dangerous about diarrhoea is how quickly it can dehydrate the body. The body loses water and critical electrolytes, resulting in such complications as low blood pressure, kidney failure, or death — more so for children, the elderly, and those with other ailments.

As per the CDC, diarrhoea-inducing pathogens — such as rotavirus, norovirus, and cholera — usually transmit through contaminated water or food. Rotavirus alone accounts for 40% of diarrhoea hospitalizations among children aged five years and under around the world.

In Odisha's situation, the lethal mix of unsafe drinking water, substandard sanitation infrastructure, and lack of access to healthcare continues to render diarrhoeal diseases a nagging public health issue.

Why Are Diarrhoea, Cholera Threats Resurfacing Frequently?

Cholera, previously much relegated to the fringes of public health issues in India's coast and cities, is now beginning to reappear. What started as a monsoon-led outbreak in tribal areas has now begun to hit semi-urban and urban coastal areas — a cause for concern.

Odisha's tribal areas have always been water-borne disease hotspots because of poor sanitation and lack of access to safe water. But this year's statistics indicate the issue is spreading beyond these confines.

Specialists consider this could be attributed to the effects of climate change, fast-paced urbanization without corresponding infrastructure, and declining oversight of food and water safety at local events. Complicating matters further is the development of antibiotic resistance in cholera strains — a cause for concern observed in previous outbreaks in the country.

Government Response: Quick Action But Enduring Gaps

Following these outbreaks, the Odisha government has gone into high gear. Rapid response teams, with paramedics and top health authorities, have been sent out to districts. Health Secretary Aswathy S has set aside no-nonsense orders, even suspending a doctor for medical misconduct in the midst of the crisis.

Central health authorities, in the meantime, have suggested immediate action: water purification at the point of distribution, raids on illicit bottlers, and hygiene campaigns.

But implementation lags exist. Residents in some of the impacted blocks complain of sporadic availability of clean water and an overburdened health system that cannot keep up with the demand. In a state celebrating one year of governance, the public health machinery is now under intense scrutiny.

Though this tale is set in an eastern Indian village, its consequences reverberate far beyond. Diarrheal illnesses claim almost 1.6 million lives annually across the world, ranking as one of the world's top 10 killers — The Lancet's 2019 Global Burden of Disease study reports.

The return of cholera and other water-borne diseases such as in Odisha is symptomatic of a larger pattern: how climate uncertainty, inadequate infrastructure, and poor regulatory environment can revive old vulnerabilities.

It also serves as a warning for travelers, especially those heading to developing regions. Though vaccines for rotavirus and cholera are available, they aren’t foolproof. Practicing safe food and water habits — drinking boiled or bottled water, avoiding raw foods, and washing hands regularly — remains essential.

Is It a Monsoon Menace or Public Negligence?

The monsoon rains are usually blamed for India's seasonal illnesses, but in the case of cyclical diarrhoea and cholera outbreaks such as the one that is currently taking place in Odisha's Ganjam district, it's not only nature that is to blame — human complacence has a much bigger role to play.

Yes, there is a possibility that heavy rain could clog sanitation systems, inundate water sources, and contribute to microbial contamination. But these situations are not unprecedented. What is worrying is the failure of the state to prepare when they are aware of such patterns. Outbreaks in eight districts within weeks — with water contamination, E. coli, and Vibrio cholerae detected — indicate systemic failures in water safety management and public health surveillance.

Another glaring lacuna is the consumption of cheap, unregulated packaged drinking water at public gatherings like festivities. Such local bottlers usually go undetected by quality checks, and food safety officials are unaware of them. Over and above that are substandard infrastructure, ineffective enforcement of hygienic standards, and little awareness campaign at the community level, and the result is nothing short of a disaster waiting to happen.

Labelling it merely a monsoon issue exculpates the guilty. This epidemic is a sign of systemic oversight, rather than seasonal bad luck. Clean water is a right, not a privilege — and until that's regarded as an absolute, these "monsoon" epidemics will keep killing.".

This Very Painful Symptom Is A Sign You’ve Got The New 'Highly Contagious' COVID Variant Stratus

Credits: Health and me

Just when the world had begun to settle into post-pandemic normalcy, a new COVID-19 variant has entered the spotlight—Stratus, a name now making headlines across the UK. If you haven’t heard of it yet, you will. Stratus, specifically its XFG and XFG.3 sub-variants, is spreading quickly and has prompted health experts to take notice.

There’s no reason to panic. The variant isn’t known to cause more severe illness or to evade current vaccines. But it is worth understanding, especially as COVID continues to evolve and resurface in new forms. The story of Stratus offers insight not just into the virus itself, but how we’ve learned to live alongside it—through better surveillance, faster response, and smarter precautions.

What Is the Stratus Variant?

Stratus is not a completely new virus—it’s a descendant of the Omicron lineage, already known for its ability to spread easily while generally causing milder illness than earlier strains like Delta.

More specifically, Stratus is what experts call a “recombinant” strain, formed when someone is infected with two variants at once and those variants mix their genetic material. This gives Stratus its nickname: the “Frankenstein” variant. There are two types of Stratus in circulation:

XFG

XFG.3, a spin-off which currently accounts for about 30% of COVID-19 cases in England, up from just 10% in May, according to the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA).

Because of its rapid spread, the World Health Organization (WHO) has classified XFG as a "variant under monitoring", urging global surveillance.

What Makes Stratus Variant Different From Other COVID Strains?

Though most symptoms of COVID haven’t changed much with each variant, Stratus may come with a new, unusual symptom: a hoarse voice.

According to some UK-based clinicians, patients infected with XFG and XFG.3 have reported hoarseness more frequently. This could be a result of the strain’s impact on the upper respiratory tract, particularly the vocal cords but here’s the thing: this is not yet a definitive diagnostic marker. Hoarseness alone doesn’t confirm infection, and not everyone with Stratus reports it. Like other variants, symptoms remain largely dependent on the person’s immune response, vaccination status, and pre-existing conditions.

What Are the Unique COVID Symptoms of Stratus?

While Stratus may bring hoarseness into the conversation, the core symptoms of COVID remain largely the same. According to the NHS and UKHSA, people infected with Stratus may experience:

- High temperature or chills

- Persistent cough

- Shortness of breath

- Loss or change in taste or smell

- Fatigue

- Headaches

- Muscle aches

- Sore throat

- Nasal congestion or runny nose

- Loss of appetite

- Diarrhea or nausea

These symptoms also overlap with seasonal flu and allergies, making it difficult to identify the variant without testing. What makes Stratus stand out so far is its hoarseness, which might be more pronounced than in previous infections.

Is Stratus COVID Variant More Dangerous?

The WHO and UKHSA have both made it clear: there’s no current evidence that Stratus leads to more severe illness, higher hospitalization rates, or death compared to other Omicron subvariants.

Dr. Alex Allen, a consultant epidemiologist at UKHSA, explained that there is no indication vaccines are less effective against Stratus. In fact, immunity—whether from vaccines, previous infection, or both—continues to offer protection, especially against serious outcomes.

It’s also worth noting that hospital admissions and case rates in the UK have been trending downward, despite the rise of Stratus. As of late June, COVID hospitalizations in England dropped from 1.46 per 100,000 to 0.99 per 100,000.

This suggests that while XFG and XFG.3 are spreading fast, they may not be driving a significant wave of severe disease.

Why Is Stratus Being Monitored?

Even though it isn’t more dangerous right now, Stratus is spreading quickly—and that alone is enough reason to monitor it closely.

The WHO notes that XFG exhibits “marginal additional immune evasion” compared to previously circulating strains. In plain terms: it might slip past some parts of the immune system, but not enough to trigger alarm bells. Still, it has been seen in multiple countries, especially in South-East Asia, where some upticks in hospitalizations have occurred.

That doesn’t mean we’re on the brink of another global surge. It does mean that global health systems remain vigilant, especially as colder months approach in the Northern Hemisphere.

How to Protect Yourself from New COVID Variants?

No matter the strain—whether it’s Delta, Omicron, or now Stratus—the same precautions still apply:

- Stay up to date on vaccinations, including boosters recommended by your local health authority.

- Test when symptomatic, especially if you’re at high risk or around vulnerable individuals.

- Practice good hygiene: wash your hands, cover your cough, and sanitize high-touch surfaces.

- Wear a mask in crowded indoor spaces if transmission is high in your area.

- Take hoarseness seriously if it appears alongside other symptoms—especially if you’ve had recent exposure.

You might be asking: If Stratus isn’t more deadly, why should I care? Here’s why. Pandemics don’t end with a bang—they evolve quietly. Variants like Stratus remind us that SARS-CoV-2 is still adapting, and we need to stay informed even when things seem calm. By recognizing symptoms early, getting tested, and staying up to date on guidance, we help protect not only ourselves but the most vulnerable among us.

So no, Stratus isn’t a reason to panic but it is a reason to pay attention because COVID hasn’t disappeared—it’s just changed its voice.

Soccer Player 'Choclo' Suffered A Type 3A Muscle Injury Causing His Absence From Match Against Delfín

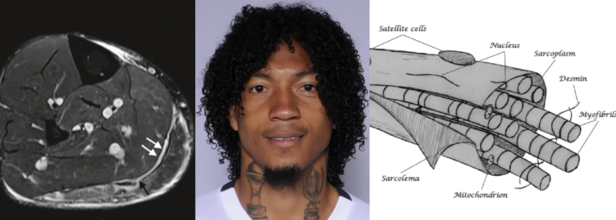

Source and in photos L to R: Minor, structural muscle injury (type 3a), source: SEMS Journal; player Choclo (source: LDU Quito); diagram of the muscle fiber, source: SEMS Journal

Liga Deportiva Univerrsitaria (LDU) has confirmed a new injury to its roster this Sunday. Defender José "Choclo" Quintero has a grade 3A muscle injury. This has been confirmed by team's official statement which has come from the club's medical department.

The player is currently undergoing rehabilitation and will begin strength training and physical therapy sessions. The official statement says that "Choclo" will have a reasonable amount of time before he returns to the field. He has so far played 19 matches and his return will depend on his progress.

José "Choclo" Qiuntero List Of Injuries

He had earlier suffered a skull fracture from August 30 2021 to October 4 2021 and as a result had missed three games in the season 21/22. Previously too in the season 16/17, he was in rehabilitation for 173 days due to a knew medial ligament tear, as a result of which he missed 31 games.

Also Read: Inner Child: Being Left Out And Rejected In Childhood Becomes A Social Seed For Deeper Connections

What Is a A 3A Muscle Injury?

As per the 2014 study published in Translational Medicine @ UniSa, Official Journal of the Medical School of the University of Salerno, a 3A muscle injury is part of the structural injuries, which are divided into 3 sub-groups as per the "entity of the lesion within the muscle".

A type 3A lesion is a minor partial lesion, which involves one or more primary fascicles within a secondary bundle.

3A Muscle Injury Symptoms

It usually is characterized by sharp pain, especially during a specific movement. The pain is, however, localized, and is easy to "appreciate on palpation and, at times, preceded by a snap sensation. On palpitation, it is not possible to detect the structural defect as it is too small and the contraction against manual resistance is painful," notes the study.

3A Muscle Injury Diagnosis

Another study from 2016, published in the journal Joints, a 3A involves a minor partial muscle tear with small maximum diameter and could be detected through MRI that shows fiber disruption.

A 2019 study published in the journal Sport and Exercise Medicine Switzerland, notes that Type 3A are of less than 5mm in size. Thus, it includes 1-5 primary muscle bundles. The study also notes that such injuries usually heal without defect, however, injury to the perimysium and the aponeurosis is found in type 3b injuries (> 5 mm), which is the cause for intermuscular hematoma formation.

Also Read: What Is Innotox? The ‘Korean Botox’ People Are Injecting At Home—And Why Doctors Are Worried

What Are The Common Muscle Injuries Among Football Players?

Type 3B injuries are moderate partial lesion, which involves at least a secondary bundle, with less than 50% of breakage surface. A Type 4 lesion is a sub-total tear with more than 50% of breakage surface or even a complete tear of the muscle. It also involves the muscle belly or the musculotendinous junction.

While these comprise structural injuries, Type 1 and Type 2 comprise the non-structural injuries.

It is the non-structural injuries, which are the most common and accounts for 70% of all muscle injuries in football players, mentions the 2014 study.

While the lesion may not be readily recognized in these injuries, they cause more than 50% of days of absence away from sport matches and training, the study notes. When they are ignored, they could turn into structural injuries.

Non-structural muscle injuries are classified into different types based on their underlying causes. Here's a breakdown of common types and what triggers them:

Type 1A Injury

These injuries are often the result of fatigue or sudden changes in training routines, running surfaces, or high-intensity activities. The muscle strain occurs due to the body not being fully adapted to new or excessive demands.

Type 1B Injury

This type of injury is linked to prolonged and excessive eccentric muscle contractions — when the muscle lengthens while under tension. This repeated strain can lead to overuse and damage.

Type 2A Injury

Type 2A injuries are typically associated with spinal issues. Often misdiagnosed, they stem from minor intervertebral disorders that irritate spinal nerves. This nerve irritation disrupts the normal control of muscle tone in specific “target” muscles. In such cases, treating the underlying spinal disorder becomes the main focus of care.

Type 2B Injury

These injuries are caused by a breakdown in the balance of the neuro-musculoskeletal system, particularly the mutual inhibition mechanism controlled by muscle spindles. When this balance is disrupted, the regulation of muscle tone suffers. Specifically, when the inhibition of agonist muscles is reduced, those muscles may become overly contracted to compensate — leading to dysfunction and injury.

You Don’t Have To Smoke To Get Lung Cancer—Air Pollution May Be Just As Dangerous

Credits: Canva

For decades, lung cancer has been synonymous with smoking. But the data is shifting—and fast. Today, 10–20% of lung cancer cases in the U.S. are found in people who have never smoked a single cigarette. A new large-scale international study has now unearthed some of the strongest evidence yet that air pollution may be a major culprit—and it’s leaving a genetic trail behind.

Researchers have discovered that fine particulate matter in polluted air, commonly from traffic, industrial emissions, and smog, is strongly associated with DNA mutations that are also found in smokers’ lung tumors. These mutations may be key drivers of lung cancer development in never-smokers.

The research, involving whole-genome sequencing of lung tumors from 871 never-smokers across 28 regions in four continents, found that individuals living in highly polluted environments had significantly more driver mutations—the kind that directly trigger cancer.

The investigators matched tumor samples with long-term air pollution exposure estimates, using ground and satellite data for fine particulate matter (PM2.5). They found that non-smokers exposed to high levels of pollution were nearly four times more likely to exhibit the SBS4 mutational signature—a genetic fingerprint commonly linked to tobacco smoke.

Additionally, they identified a 76% increase in a separate signature associated with accelerated biological aging. This is alarming, considering these were individuals with no direct tobacco exposure.

What makes this finding even more significant is that researchers discovered TP53 and EGFR mutations—both known to be aggressive lung cancer markers—more frequently in people living in polluted areas. These genetic changes are typically hallmarks of cancers in smokers.

This implies that air pollution could be triggering similar molecular pathways to those activated by cigarette smoke.

But there was a twist: a new mutational signature, SBS40a, was found in 28% of never-smokers but not in smokers. The origin of this marker remains unclear, but it suggests that pollution may not be the only hidden risk.

Rise of Environmental Carcinogens

The study adds to a growing body of evidence that air pollution is not just an irritant—it’s a carcinogen. Fine particles can be inhaled deep into the lungs, where they may damage DNA directly or trigger chronic inflammation that promotes tumor growth.

Even more surprising, another carcinogen showed up in the data: aristolochic acid, found in some traditional Chinese herbal remedies. This compound was associated with a distinct mutational signature in patients from Taiwan, hinting at a possible secondary environmental risk factor for lung cancer in never-smokers.

The rise of lung cancer in non-smokers is especially noticeable in East Asia, where rates remain disproportionately high—particularly among women. While genetic predisposition may play a role, this new evidence points clearly to environmental exposures as a key contributor.

And it’s not just an Asian problem. In Western countries, urban dwellers are also exposed to dangerously high levels of air pollution. The World Health Organization estimates that 99% of the world’s population breathes air that exceeds safe pollution thresholds. This means the risk is truly global.

The power of this new research lies in its use of whole-genome sequencing to link pollution to DNA changes. These mutational signatures act as a kind of molecular journal, recording every environmental insult a cell has endured.

The ability to map those changes and match them to known pollutants gives researchers a more precise way to trace cancer origins—not just infer them from epidemiological studies.

While this study can’t definitively prove causation, the strong correlation between pollution exposure and cancer-driving mutations makes it clear that dirty air is more than just a nuisance—it's a potential trigger for deadly disease.

Researchers acknowledge some limitations. Pollution estimates were regional, not personal, meaning it’s unclear how much exposure each participant had. Self-reported smoking histories can also be unreliable.

Still, the pattern is unmistakable. Air pollution behaves like a mutagen, leaving behind signatures that align with known cancer mechanisms. And it appears to affect never-smokers in a strikingly similar fashion to tobacco users—down to the very DNA damage.

This study raises serious public health questions: If environmental exposure to polluted air can cause DNA mutations tied to cancer, what safeguards are in place to protect those most vulnerable?

Governments and public health agencies may need to reconsider air quality regulations, urban zoning, and access to clean air—especially in densely populated cities where pollution levels remain dangerously high.

Healthcare systems might also need to adapt. Traditional lung cancer screenings focus on long-time smokers, but this research could shift how we think about early detection in non-smokers, especially those living in high-risk environments.

Lung cancer has long been viewed through the lens of personal responsibility: if you smoked, you knew the risks. But this research changes that narrative. The air we breathe—something no one can fully avoid—is now emerging as a significant threat.

For non-smokers around the world, especially women and urban residents, this is a wake-up call. Your lungs may be at risk not because of personal choices, but because of public ones—decisions about pollution control, urban planning, and clean energy.

The future of lung cancer prevention may lie not just in quitting cigarettes, but in cleaning up the air we all share.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited