- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

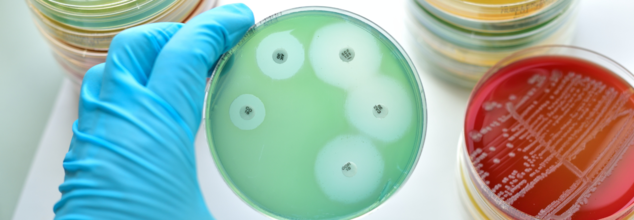

IIIT-Delhi, French Team Develop AI Tool To Tackle Antimicrobial Resistance

Credits: Canva

In a promising step towards tackling the global health crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), researchers from the Indraprastha Institute of Information Technology Delhi (IIIT-Delhi), India, and Inria Saclay, France, have developed a powerful artificial intelligence (AI) tool. This new system is designed to help clinicians identify effective treatments for drug-resistant bacterial infections by repurposing existing antibiotics, potentially transforming infection management worldwide.

Understanding the Threat of AMR

Antimicrobial resistance occurs when bacteria evolve to resist the effects of antibiotics, making once-effective drugs useless. This growing issue threatens to turn minor infections like urinary tract infections or pneumonia into life-threatening conditions. The problem is especially severe in low- and middle-income countries, where over 70% of hospital-acquired infections are resistant to at least one widely used antibiotic.

Adding to the challenge is the slow pace of antibiotic development. Creating a new drug often takes over ten years and involves substantial financial investment. As a result, scientists and clinicians are increasingly looking to drug repurposing—finding new uses for existing medications—as a faster, more cost-effective solution.

How the AI Tool Works

To support this strategy, a team led by Dr. Emilie Chouzenoux from Inria Saclay and Dr. Angshul Majumdar from IIIT-Delhi has developed a hybrid machine learning algorithm that can recommend treatment alternatives for resistant infections. Other key team members include research engineer Stuti Jain and graduate students Kriti Kumar and Sayantika Chatterjee.

What sets this tool apart is its unique blend of clinical and molecular data. Instead of relying solely on rigid databases or predefined rules, the AI model learns from real-world treatment guidelines provided by top Indian hospitals. It then integrates this information with bacterial genomic data and the chemical structures of antibiotics to identify effective, lesser-known alternatives.

Tested Against Deadly Pathogens

The AI system was tested on several challenging pathogens known for their resistance to treatment:

- Klebsiella pneumoniae, which causes hospital-acquired pneumonia and bloodstream infections

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae, responsible for gonorrhea, which is increasingly difficult to treat

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes tuberculosis

In each case, the AI tool successfully recommended antibiotics that had either proven effectiveness or strong potential for repurposing. These results were validated by resistance data and clinical experts.

A Global Solution for a Global Problem

“This is an excellent example of how AI and international collaboration can come together to solve real-world medical challenges,” said Dr. Majumdar. He added that this approach makes better use of existing medical knowledge and enables quicker, smarter responses to the AMR crisis.

Designed for scalability, the AI system can be integrated into hospital networks or public health programs, especially in settings with limited diagnostic tools. It not only aids in timely treatment decisions but also supports responsible antibiotic use.

By linking clinical expertise with molecular science, this innovation marks a significant leap in the global fight against AMR—showcasing how collaborative, data-driven technologies can pave the way for better healthcare solutions.

Six-year-old Child Dies Of Medical Negligence During MRI At Greater Noida Imaging Centre

Credits: Canva

A six-year-old boy died after his health worsened during an MRI scan at a private Greater Noida diagnostic centre. His family alleged medical negligence and claimed that he was administered a wrong or heavy dose injection.

As per the boy's father, Prashant Kasana, his son was taken to the centre for some test and was given an injection before the MRI procedure. The family said that during the MRI scan, the child was administered a heavy dose. Due to which his condition worsened and he also lost consciousness.

The family also said that when they asked for information about the child's condition and his medical report, they were not given any satisfactory answers. They also claimed that the doctors gave another dose to the child. The child's condition did not improve and the family had to rush the child to another nearby private hospitals. This is where the doctors declared him dead.

Six-year-old Child Dies of Medical Negligence: What Happened?

After this incident, family members accused the staff of the KB Healthcare Centre, where the child was first taken for an MRI scan. Villagers and workers of the Bharatiya Kisan Union also reached the spot and staged a protest.

The state spokesperson of the Bharatiya Kisan Union, Pawan Khatana, stated that the child was brought to the centre at 10.30am, and was in normal condition. As per the spokesperson, doctors did not disclose the quantity of the dose administered to the child.

As per Khatana, even after half an hour, the child did not gain consciousness and when the doctors checked him again, he was unresponsive and cold. The family took to another private hospital where he was declared dead. Khatana also alleged that there are many such unauthorized screening and imaging centres operating in Greater Noida and demanded a thorough probe.

Six-year-old Child Dies Of Medical Negligence: What Are The Authorities Saying?

Police on reaching the spot received the information, while protesters demanded for a fair investigation and strict action against those responsible. The Station House Officer of Neta 2 police station said the child was a resident of Reelkha in Dankaur. He was brought to a private pathology lab in Sector P3 for an MRI scan. As per the officer, the doctor administered the child with anesthesia for an MRI. After this, the child's health started to deteriorate.

Police has sent the body for post-mortem after completing the necessary legal formalities.

Six-year-old Child Dies of Medical Negligence: How Much Anesthesia Is Safe For A Child During MRI?

As per the National Institutes of Health (NIH), US and a study by the Yeungnam University Journal of Medicine (YUJM), drugs for deep sedation or general anesthesia for pediatric MRI are:

(I) Chloral hydrate: a sedative hyptonic agent with no analgesic properties

The study notes that the recommended dose of chloral hydrate is 50 to 100 mg/kg, or up to a maximum of 2g. The success rate of chloral hydrate sedation for pediatric MRI varies from 78% to 100%.

The United Kingdom (UK) National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) also recommends the use of oral chloral hydrate with a wide margin of safety in children under 15 kg.

The study also notes that children "may be encouraged to take at least clear fluids 2 hours before the procedure for successful sedation without breaking institutional fasting protocols for chloral hydrate sedation".

(II) Pentobarbital: a medium duration barbiturate that provides potent sedation with no analgesic property.

As per the study, this can be administered via an oral or intravenous or IV route. The oral dose is administered between 4 to 8mg per kg and IV dose of 2 to 3 mg per kg.

(III) Midazolam: it is a short-acting water soluble benzodiazepine that has anxiolytic, sedative, amanestiec, and muscle relaxant properties.

It is administered through various routes, but IV is preferred. When administered through IV, it is given at the dose of 0.1mg per kg.

Anesthetic agents include propofol and sevoflurane.

Note: This article is not a substitute for medical consultation or prescription. The information is based on reports and research articles available online for public.

Trump's Slurred Speech At Champion of Coal Event Sparks Health Concerns

(Credit - The White House/X)

President Donald Trump’s slurred speech at a recent event has sparked renewed concerns for his health. During a White House ceremony, where President Trump was being crowned the “Undisputed Champion of Coal”, his speech briefly slurred and he mispronounced the word, “undisputed.”

A video clip of him saying “And I'm proud to officially name the undithpuut... When did this come out, Mr speaker.” has been making rounds on social media platforms like X. Speculations about President Trump’s dementia and memory loss have been taking over the internet. People are also drawing between the supposed email mentioned in the Epstein files that also mentioned Trump’s supposed memory loss and the continued rumors about his dementia.

Also read: Epstein Files Raise Questions About Trump’s Memory Decline

Is Slurred Speech A Sign of Dementia?

According to Harvard Health, yes, slurred speech can be a sign of dementia, more specifically vascular dementia. While many people associate dementia primarily with memory loss seen in Alzheimer’s, vascular dementia has a different cause and set of symptoms.

Vascular dementia is the second most common form of the condition. It is caused by reduced blood flow to the brain, often due to cholesterol-clogged vessels or a series of "silent" mini-strokes.

Health Conditions That Can Cause Slurred Speech?

Harvard health also explains that slurred speech typically appears in two scenarios

Following a Major Stroke

A significant blockage can cause an abrupt mental shift, often paired with physical symptoms like paralysis or slurred speech.

As a Core Symptom

Because symptoms depend on which specific area of the brain is damaged, some individuals may experience slurred speech and confusion even if their memory remains relatively intact.

Also Read: Donald Trump Alzheimer’s Speculation Rises After Niece Notices Worrying Sign

Trump’s Dementia Speculations

With the influx in conversation surrounding the health of President Donald Trump, it is important to remember that these are not proven claims. On social media, people often point to these "fumbles" as evidence of the president’s cognitive decline or dementia. However, we must understand that the situation is much more complex than that

The White House maintains that the President is in "excellent overall health" and has even released MRI results to back that up. Trump himself often pushes back aggressively against the media for questioning his fitness.

While the public is quick to speculate, experts like neurologists and specialists in aging, say we should be careful. They argue it is impossible, and unprofessional, to diagnose someone just by watching them on TV.

Other Reasons Why Trump’s Health Made News

In 2025, public debate frequently centered on President Trump’s physical health, sparked by visible signs like hand bruising and swollen ankles.

Hand Bruising

Health doubts had been sparked when a bruise on Trump’s hand was highlighted. However, the White House clarified that the bruising on his right hand was a common side effect of daily Aspirin use for heart health, potentially worsened by frequent handshaking.

Swollen Ankles

Similarly, his swollen ankles during the ASEAN summit were attributed to Chronic Venous Insufficiency (CVI), a condition where leg veins struggle to pump blood back to the heart, in an official report from the White House.

MRI Scan

Official MRI results of President Trump also described his cardiovascular and abdominal health as "excellent,". This was shared by Dr. Sean Barbabella, the White House physician, who said that the scans were routine checkups for a 79-year-old and were exceptional for his age.

Cognitive Screening

Trump claimed he "aced" an IQ test, but experts identified it as the MoCA dementia screening. This basic 10-minute exam checks for cognitive impairment rather than measuring a person's general intelligence.

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: Nurse Who Recovered Dies Of Cardiac Arrest

Credits: Canva

Nipah virus Outbreak In India: After two cases of Nipah virus were confirmed in Kolkata, one of the nurses who has recovered from Nipah virus died of a cardiac arrest. Health and Me previously reported on the male nurse being discharged.

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: What Happened With The Nurse?

The 25-year-old nurse who recovered from Nipah virus infection died of cardiac arrest on Thursday. As per the official statement given to news agency PTI, "She died of cardiac arrest this afternoon. Though she had recovered from Nipah infection, she was suffering from multiple complications."

The reports show that she also developed a lung infection and contracted a hospital-acquired infection during treatment. The official said, "She was trying to regain consciousness, move her limbs, and speak before her condition suddenly deteriorated. She died at around 4.20pm."

The nurse fell ill in early January after returning home on December 31 for the New Year holidays and was initially admitted to Burdwan Medical College and Hospital before being shifted to the private hospital in Barasat.

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: What Is Nipah Virus?

As per the World Health Organization (WHO), Nipah virus infection is a zoonotic illness that is transmitted to people from animals, and can also be transmitted through contaminated food or directly from person to person.

In infected people, it causes a range of illnesses from asymptomatic (subclinical) infection to acute respiratory illness and fatal encephalitis. The virus can also cause severe disease in animals such as pigs, resulting in significant economic losses for farmers.

Although Nipah virus has caused only a few known outbreaks in Asia, it infects a wide range of animals and causes severe disease and death in people.

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: What Are The Common Symptoms?

- Fever

- Headache

- Breathing difficulties

- Cough and sore throat

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Muscle pain and severe weakness

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: What Are Experts Saying?

Dr Krutika Kupalli, a Texas-based expert who formerly also worked with the World Health Organization (WHO), told The Daily Mail that the possibility of Nipah virus outbreak is 'absolutely' something the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) should be 'closely monitoring'.

Read: Experts Reveal Risks Of Nipah Virus Outbreak In The US, CDC On Alert

“Nipah virus is a high-consequence pathogen, and even small, apparently contained outbreaks warrant careful surveillance, information sharing, and preparedness. Outbreaks like this also underscore the importance of strong relationships with global partners, particularly the WHO, [which] plays a central role in coordinating outbreak response and sharing timely, on-the-ground information," she said.

A CDC spokesperson told The Daily Mail that the agency is in 'close contact' with authorities in India. "CDC is monitoring the situation and stands ready to assist as needed."

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited