- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

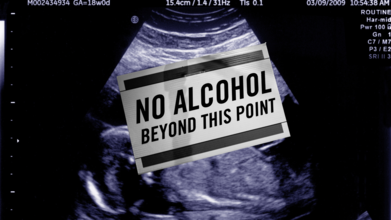

International Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Day 2025: Themes, Significance And History

Credits: Canva

September is globally recognized as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Awareness Month, with September 9 dedicated to International FASD Awareness Day. This year, 2025, carries the powerful theme “Everyone Plays a Part: Take Action!”, a reminder that preventing FASD and supporting those affected is a collective responsibility.

What is FASD and Why It Matters

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) describes the lifelong effects on the brain and body of a baby exposed to alcohol during pregnancy. It can lead to physical, behavioral, and cognitive challenges that persist throughout life. The most severe form, fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), is characterized by distinct facial features, slow growth, learning difficulties, and developmental delays.

Also Read: Kissing Bugs Disease Could Soon Become An Endemic, Says CDC

FASD Theme 2025

This year’s theme, “Everyone Plays a Part: Take Action!”, is a call to collective responsibility. It highlights that FASD prevention is not just about individual choices but also about community support, healthcare education, and creating safe environments for expectant mothers.

Health professionals are encouraged to screen for alcohol use early in pregnancy, families are urged to provide support to those struggling with alcohol dependence, and policymakers are called upon to ensure inclusive systems for people with FASD. The message is simple yet powerful: prevention and support require all of us.

Experts emphasize that there is no known safe amount of alcohol to consume during pregnancy. Alcohol passes through the placenta to the developing baby, where it can cause permanent brain damage and affect organ development.

Also Read: What Role Do Genes Play In Alcoholism?

Symptoms vary, some children may face intellectual disabilities, behavioral issues, or difficulty with learning and social interaction. Others may experience challenges with coordination, speech, and growth.

The disorder is entirely preventable by avoiding alcohol during pregnancy. However, for those already living with FASD, early diagnosis and intervention can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life.

How FASD Awareness Day Began

International FASD Awareness Day was first observed on September 9, 1999, thanks to the efforts of parents and advocates like Bonnie Buxton, Brian Philcox, and Teresa Kellerman. They chose 9/9/99 to symbolize the nine months of pregnancy, a clear reminder that avoiding alcohol throughout those months can prevent FASD entirely.

What started as a grassroots effort in Canada and the United States has grown into a global movement. Communities worldwide now hold events, educational workshops, and social media campaigns each September to raise awareness, combat stigma, and advocate for better support systems.

Why This Day Matters

FASD Awareness Day is more than an observance, it is a global reminder that thousands of children are still born each year with preventable conditions linked to alcohol exposure. Beyond prevention, the day pushes for better understanding and empathy toward individuals already living with FASD. Stigma often keeps families from seeking help, and awareness campaigns aim to break that silence.

As the world observes FASD Day 2025, the message is clear: by spreading awareness, encouraging alcohol-free pregnancies, and supporting those affected, society can take a step closer to ending preventable harm and building inclusive communities where individuals with FASD can thrive.

Donald Trump Mistakes Cognitive Exam For IQ Test; Experts Say His Confusion May Be A Sign Of Dementia

Credits: Canva

US President Donald Trump recently claimed he had taken an “IQ test,” seemingly mistaking it for a dementia screening exam. Boasting that he achieved a perfect score, he also challenged Democratic representatives Jasmine Crockett and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) to attempt the same test.

Speaking aboard Air Force One, the 79-year-old described the exam as “very hard,” while mocking his opponents as “low IQ” individuals. This mix-up has once again drawn scrutiny to his cognitive health, with experts suggesting the confusion could be a possible sign of dementia.

Donald Trump Mistakes Cognitive Exam For IQ Test

On Monday (October 27), Trump told reporters that he had aced an intelligence test at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington D.C. According to The New Republic, the test he referred to is likely the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), a short 10-minute screening tool designed to detect early signs of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. Despite this, Trump appeared to treat it as an intelligence measure rather than a diagnostic tool.

During his remarks, the Republican challenged Crockett, 44, and Ocasio-Cortez, 36, to take what he called the “IQ test.” “Let Jasmine go against Trump,” he said. “The first couple of questions are easy: a tiger, an elephant, a giraffe, you know. But when you get up to about five or six, and then 10, 20, 25—they couldn’t answer any of them,” he added.

Donald Trump’s Verbal Gaffes

This is not the first time Donald Trump has spoken about the MoCA test in exaggerated terms or made verbal missteps. Back in 2020, he told Fox News that he was asked “30 to 35 questions” of varying difficulty. “They always show you the first one, like a giraffe, a tiger, or a whale—‘Which one is the whale?’ OK. And then it gets harder and harder,” he said at the time, insisting that others had struggled where he had not.

Observers have long noted that Trump’s speeches often include rambling detours and non-sequiturs. “His speeches are full of non sequiturs,” said historian Kristin Kobes Du Mez of Calvin College, who has compared the speaking styles of Trump and Hillary Clinton. “It’s a completely different style from nearly any other politician you normally see on a big stage.”

Is Donald Trump Showing Early Signs of Dementia?

Clinical psychologists Dr. Harry Segal and Dr. John Gartner have expressed concern about the president’s psychomotor performance, suggesting that he may be displaying early indicators of dementia. Speaking in a recent episode of their program Shrinking Trump, Dr. Gartner said, “We’ve been observing a clear decline in his motor performance, which aligns with dementia, as it typically involves deterioration across all faculties and functions.”

He added that Trump’s public demeanor, language, and verbal disorganization have become more apparent signs of cognitive changes. According to The Mirror, Trump has also been seen attempting to conceal his hands in public, prompting further speculation about his health.

The recent mix-up between the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and an IQ test, some experts say, could further reinforce these concerns. To better understand this, we spoke with Dr. Neetu Tiwari, MBBS, MD (Psychiatry), Senior Resident at NIIMS Medical College & Hospital.

She explained, “Confusing the nature of the test could be something worth noting. In itself, a single instance of confusion does not amount to a diagnosis of Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) or any other dementia type. But if this kind of misunderstanding is part of a wider pattern—repeated confusion, new behavioural changes, personality shifts, language difficulties, or problems managing daily tasks—it would justify a full cognitive and neurological assessment. Early detection often relies on observing clusters of symptoms that persist or worsen over time.”

Summing up her view, Dr. Tiwari added that while it is possible for such mislabelling to be a small indicator, it is not strong evidence on its own. “Context matters,” she said. “Age, baseline cognitive ability, education, emotional state, stress, and fatigue all influence mental performance. The responsible next step is to monitor whether other changes are taking place, and if so, to seek a detailed evaluation from a neurologist or neuropsychologist.”

Morning-After Pill To Be Offered Free At 10,000 Pharmacies Across England: What You Should Know

Credits: Canva

The NHS has made the morning-after pill available for free in pharmacies across England, aiming to eliminate the “postcode lottery” that limited access to emergency contraception. Nearly 10,000 pharmacies can now provide the pill without charge, meaning women no longer need to visit a GP or book an appointment at a sexual health clinic to access it. Previously, some pharmacies charged up to £30 for the emergency pill.

Free Emergency Contraception Now Available at Pharmacies

Thousands of women in England can now access the morning-after pill for free from local pharmacies under the government’s NHS reforms, which are designed to make healthcare services more accessible without requiring GP appointments.

Research suggests that one in five women aged 18 to 35 will need emergency contraception each year. The pill can be taken up to five days after unprotected sex to prevent pregnancy.

Before this change, women had to buy the pill over the counter for as much as £30 or seek it free from GPs and sexual health clinics. However, both options often came with barriers such as appointment delays or reduced clinic availability due to funding cuts. With the pill being most effective when taken soon after unprotected sex, the NHS move has been welcomed by health advocates as a timely and practical step.

Where Can You Get the Free Morning-After Pill?

As reported by The Independent, around 10,000 pharmacies in England, including major chains like Boots and Superdrug, as well as independent outlets, are now offering the morning-after pill free of charge.

Claire Nevinson, Superintendent Pharmacist at Boots, said that pharmacists can also provide confidential advice on contraception choices. “Expanding the NHS Pharmacy Contraception Service to include access to emergency hormonal contraception is a significant step forward in helping women get timely healthcare,” she explained.

“Women can visit their local Boots pharmacy for free contraception advice, support, and medication—without needing a GP or clinic appointment.”

What Was the Situation Before This Change?

Until this rollout, women often had to make an appointment at a clinic or contact their GP to obtain emergency contraception, which sometimes led to delays, especially over weekends or in rural areas. Under the new plan, women of reproductive age can now walk into any participating pharmacy and speak directly with a trained pharmacist. Consultations are private, and the pill is dispensed immediately if appropriate.

This initiative adds to a growing list of NHS pharmacy services, which now include starting or continuing regular birth control, getting advice after beginning antidepressants, and receiving blood pressure checks and vaccinations. The goal is to make local pharmacies a convenient first stop for everyday healthcare needs.

A Step Toward Easier Access

The new scheme represents a broader effort to expand women’s healthcare access across the country. By making emergency contraception free and widely available, the NHS hopes to remove financial and logistical barriers that previously prevented timely use.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice or diagnosis. Always seek the guidance of your doctor or another qualified healthcare professional regarding any medical questions or concerns.

Prazosin Hydrochloride: FDA Recalls Blood Pressure Medication After Detecting Cancerous Substance

Credits: Canva

Blood pressure medication recall: More than half a million bottles of blood pressure medicine have been recalled due to the presence of a potential cancer-causing chemical, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, headquartered in Parsippany, New Jersey, issued a voluntary recall on October 7, 2025, for certain batches of prazosin hydrochloride capsules.

The FDA later classified the situation as a Class II risk on October 24, 2025, which means that use or exposure could cause temporary or medically reversible health issues, though the chance of serious harm is considered low.

Prazosin hydrochloride: FDA Recalls Blood Pressure Medicine

Teva Pharmaceuticals announced the voluntary recall after the FDA identified a potential impurity in some batches of prazosin hydrochloride. A Class II classification indicates that exposure to the affected medication could cause short-term or reversible health problems, but the likelihood of severe consequences is low.

Prazosin hydrochloride is an FDA-approved medication for treating high blood pressure, but it is also prescribed off-label to help people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) manage nightmares and sleep disturbances. The drug works by relaxing blood vessels, which helps lower blood pressure and improve blood flow.

Blood Pressure Medication Recall: What Chemical Impurity Caused the Blood Pressure Medication Recall?

The recall applies to three different dosage strengths that were distributed across the United States. The affected capsules were found to contain elevated levels of N-nitroso prazosin impurity, a nitrosamine compound that may increase the risk of cancer with prolonged exposure.

The FDA has stated that nitrosamine impurities like N-nitroso Prazosin impurity C can be harmful over time. However, because the recall falls under the Class II category, the potential for serious or long-term effects is low. In total, more than 580,000 bottles of prazosin hydrochloride are included in the recall. Patients currently taking the medicine for blood pressure or other conditions are advised to check their bottles, contact their pharmacist, and safely dispose of any affected medication.

Prazosin hydrochloride: Blood Pressure Recalled Products

According to USA Today, the recall involves the following:

- 1 mg capsules: 181,659 bottles (NDC 0093-4067-01 and 0093-4067-10), lot numbers 3010544A and 3010545A, with an expiry date of October 2025.

- 2 mg capsules: 291,512 bottles (NDC 0093-4068-01 and 0093-4068-10) across several lot numbers, expiring between October 2025 and July 2026.

- 5 mg capsules: 107,673 bottles (NDC 0093-4069-01, 0093-4069-52, and 0093-4069-05) across various lot numbers, with expiry dates extending into 2026.

Prazosin hydrochloride: What Should People Do With Recalled Medication?

Although neither Teva nor the FDA has issued specific instructions for patients, GoodRx advises those affected to verify their medication’s lot number, contact their pharmacist and prescribing doctor, and dispose of the recalled product safely.

Teva has started notifying customers by mail, and the recall process is ongoing. Patients with questions are encouraged to speak with their healthcare provider or pharmacist to confirm whether their prescription is part of the recall and discuss suitable alternatives if needed.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited