- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Is The Viral 'Quad-demic' Still Swirling? Know The Good, Bad And Ugly

Image Credit: Health and me

There's been an alarming increase of respiratory and gastrointestinal viruses in the United States lately, causing anxiety about a so-called "quad-demic". According to surveillance reports, influenza, COVID-19, RSV and norovirus are at very high levels everywhere. While the surge aligns with patterns typical for this season, several epidemiologists view simultaneous infections of such proportions to pose risks not only to individual healthcare but public health.

The incidence of the quad-demic should vary with seasonal patterns, vaccination rates, and public health interventions. Each virus alone is relatively easy to manage; however, the effect of all together could lead to overburdening of health care facilities and increase risks for those at higher risk. Continuing surveillance, early testing, and proactive prevention measures will play an important role in the control of these infections going forward.

While the term "quad-demic" sounds daunting, it must be taken into perspective. For years, we have had all these viruses together, and we have the capabilities to mitigate some of the risk. Vaccination, proper hygiene and using common sense helps individuals get through the season unscathed. Is the quad-demic a permanent fixture or just another seasonal wave? Let's break this down.

What is the Quad-demic?

Typically, flu, COVID-19, and RSV have been the primary culprits behind seasonal respiratory infections. However, norovirus, a highly contagious stomach bug, has emerged as a fourth significant player, inducing fears of a more severe and widespread viral outbreak. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. recorded nearly 500 norovirus outbreaks between August and December 2023, a substantial rise from the previous year’s numbers.

While the term "quad-demic" may sound ominous, the seriousness and consequences of such infections should be weighed in light of the U.S. healthcare system's experience with managing viral surges since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Influenza (Flu)

Flu continues to be one of the most common and alarming seasonal illnesses. In the period spanning from 2023 to 2024, there were approximately 40 million cases of flu, and thousands of hospitalizations along with reported 47 deaths have been reported this season. Flu symptoms include fever, chills, cough, sore throat, muscle pain, and fatigue, with most recovering within a week or two but risky factors for severe illness effects occur in young children, elderly, and people with chronic conditions.

2. Covid-19

Despite its reduction from the first pandemic peak, COVID-19 is still rampant. The CDC estimates that alone between October and December 2023, there were between 2.7 and 5 million cases in the U.S. Hospitalization has increased by cities such as Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York. Symptoms are closely similar to the flu, fever, cough, and fatigue but uniquely presents in some cases as loss of taste and smell.

3. RSV

RSV is the most common cause of lower respiratory infections in infants, older adults, and immunocompromised individuals. While RSV peaked late in 2023 and early 2024, it continues to be a threat because it can lead to bronchiolitis and pneumonia. It is very similar to the common cold, presenting with symptoms such as congestion, runny nose, coughing, and fever, which can make it difficult to differentiate from flu or COVID-19 without testing.

4. Norovirus

Norovirus, also called the "stomach flu," is a highly contagious infection of the gastrointestinal tract, not a respiratory virus. It transmits quickly from contaminated food and water and contact with contaminated surfaces, causing such symptoms as diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, and stomach pain. Cases have shot up, the CDC said Monday, with reports of outbreaks surging compared with last year.

Is There a Challenge In Diagnosis Due to Overlapping Symptoms?

The greatest challenge during the quad-demic is how the four viruses are alike and thus make identification very hard with no testing applied. Most cases present symptoms common to all viruses: fever, tiredness, body pains, and respiratory, which includes coughing and congestions for influenza, COVID-19, and RSV; the other would be norovirus symptoms as nausea and vomiting can appear even in extreme influenza and COVID-19. This overlap increases the risk of misdiagnosis and delayed treatment, hence the need for early testing and proper medical guidance.

Also Read: Is US Preparing For A Quad- demic 2025?

Effective Prevention Strategies That Work

The best defense against these viruses is a combination of vaccines, hygiene, and lifestyle precautions. While lifestyle modifications are highlighted as part of the constant need to eat healthy, ensure daily movement and drinking adequate amount of fluids. There is a sure short two preventive strategies that are effective:

Vaccination

- Flu vaccine: Annual flu shots reduce the severity of infection, allergic flare ups and hospitalizations.

- COVID-19 vaccine: Though COVID-19 cases have declined, vaccination remains critical in preventing severe outcomes.

- RSV vaccine: Available for those aged 60 years and older, especially those with underlying conditions.

- Norovirus vaccine: No vaccine is yet available, but mRNA vaccine research is in progress.

Hygiene and Sanitation

- Washing hands frequently with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, especially after public exposure.

- Disinfect frequently touched surfaces regularly, use sanitiser when outside.

- Avoid close contact with infected people and wear masks.

Do You Need To Wear A Mask All The Time?

While debates on masked wear continue on, experts on mask-wear affirm that this does not only have a historical precedent but works towards reducing airborne viruses spreading within the environments. Hospitals, though, ensure masking in key sections of themselves. Publicized mask-wear remains a discretion, though massing indoors still goes a longer way in cases like peak flu seasons.

If you notice the symptoms of these viruses, then it's best to be confined at home and avoid having face-to-face interaction with others and seek immediate attention from your physician if your condition worsens. Quarantining for some days can decrease the spread of infection.

As we move into the first half of 2025 and beyond, staying informed and proactive is the best strategy for maintaining health and avoiding unnecessary panic. The key takeaway? Stay vigilant, but don’t be alarmed—these viruses are here, but so are the means to fight them.

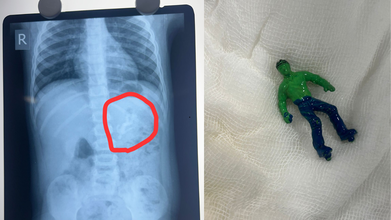

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy, Showed X-Ray, Doctors Remove It Via Endoscopy

Credits: X

Ahmedabad toddler, one-and-a-half-year-old boy swallowed a 'Hulk' toy, which is based on a popular comic superhero. The toy was stuck in his stomach when his parents took him to the Civil Hospital. According to reports by News18, the child is identified as Vansh who showed the signs of discomfort and began vomiting. This is what alarmed the parents.

As per the News18 report, his mother Bhavika was suspicious when she noticed that one of his toys was missing. The child was rushed to the hospital and an X-ray revealed that he had swallowed the entire plastic toy. The toy was not broken.

Hindustan Times reported that Dr Rakesh Joshi, Head of the Department of Pediatric Surgery removed the toy through upper GI endoscopy. "Had it been a little late, the toy could have moved further from the stomach and got stuck in the intestines. In that case, there would have been a risk of intestinal blockage and even rupture," the senior doctor said.

"There is a natural valve between the esophagus and the stomach. The biggest challenge was to take out a whole toy through this valve. When we tried to grab it with the endoscope, the toy kept slipping because of the air in the stomach. Pulling the toy by its hand or foot raised the possibility of it getting stuck in the valve and causing it permanent damage," he said.

The doctor noted that if the toy had further slipped down, it would have increased the risk of intestine rupturing.

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy: What Parents Must Keep In Their Mind

Under the Toys (Quality Control) Order, 2020 issued by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, toy safety in India was brought under mandatory BIS certification from September 1, 2020. The move aims to ensure safer toys for children while also supporting the government’s policy of curbing non-essential imports.

Industry sources estimate that more than 85 percent of toys sold in India are imported. Officials say the Toys Quality Control Order is a key step in preventing the entry of cheap and substandard toys into the domestic market, many of which fail to meet basic safety requirements.

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy: Standards for Electric and Non-Electric Toys

The quality control order clearly defines safety standards based on the type of toy. Non-electric toys such as dolls, rattles, puzzles, and board games must comply with IS 9873 (Part 1):2019. These toys do not rely on electricity for any of their functions.

Electric toys, which include at least one function powered by electricity, are required to meet the standards outlined under IS 15644:2006. Compliance with these standards is mandatory before such toys can be sold in the Indian market.

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy: Risks Linked to Untested Toys

Toys that are not tested by NABL-accredited toy testing laboratories can pose serious health risks to children. Sharp edges and poorly finished parts can cause cuts and injuries. PVC toys may contain phthalates, which are considered harmful chemicals.

Many low-quality toys have also been found to contain lead, a substance known to be particularly damaging to brain development in children. Soft toys with fur or hair can trigger allergies or become choking hazards. In some cases, small body parts can get stuck in gaps or holes, increasing the risk of injury.

Testing by NABL-accredited laboratories ensures that toys are safe, durable, and suitable for specific age groups. Parents are advised to check for IS marks on toys before purchasing, as this indicates compliance with Indian safety standards.

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy: What Parents Should Check Before Buying Toys

Experts recommend avoiding toys with small detachable parts for toddlers and young children, as they are more likely to put objects in their mouths. Toys should always match the child’s age, skill level, and interests.

Parents are also urged to look for IS marks, which confirm that the toy has been tested and certified. Loud toys should be avoided, as prolonged exposure to sounds above 85 decibels can harm a child’s hearing.

Electric toys with heating elements should be used with caution or avoided altogether due to burn risks. Finally, toys with sharp edges or shooting components should be carefully examined to prevent cuts and injuries.

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: Myanmar Airport Tightens Health Screenings

Credits: iStock

Nipah virus outbreak in India triggered airport screenings of travelers, including in Myanmar. Many reports claim that passengers are being checked in similar ways as they were during the COVID-19 virus spread. Health and Me reported how in Thailand the health screenings of foreign travelers were taken seriously, a similar case is seen in Myanmar.

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: How Are Travelers Screened In Myanmar?

Myanmar has tightened its health screenings and surveillance at Yangon International Airport to prevent any possible entry of Nipah virus case, reported The Global New Light of Myanmar. Travelers who are arriving from India, especially West Bengal are given special attention to check for any fever or other Nipah-related symptoms, read the report by the Ministry of Health.

The ministry also noted that health screening of passengers arriving from abroad is being conducted in line with the established guidelines for infectious diseases that could give rise to public health emergencies, Xinhua news agency reported.

Informational leaflets too are being distributed among travelers to be aware of the symptoms. Posters are also displayed at the airport. Along with all that, disease prevention and control measures are also being carried out in the airport.

Screening measures are also enhanced and implemented at Mandalay International Airport.

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: What Is It?

As per the World Health Organization (WHO), Nipah virus infection is a zoonotic illness that is transmitted to people from animals, and can also be transmitted through contaminated food or directly from person to person.

In infected people, it causes a range of illnesses from asymptomatic (subclinical) infection to acute respiratory illness and fatal encephalitis. The virus can also cause severe disease in animals such as pigs, resulting in significant economic losses for farmers.

Although Nipah virus has caused only a few known outbreaks in Asia, it infects a wide range of animals and causes severe disease and death in people.

Nipah virus is infectious and can spread from animals like bats and pigs to humans through bodily fluids or contaminated food. It can also pass between people through close contact, especially in caregiving settings. While it can spread via respiratory droplets in enclosed spaces, it is not considered highly airborne and usually requires close, prolonged contact for transmission. Common routes include direct exposure to infected animals or their fluids, consuming contaminated fruits or date palm sap, and contact with bodily fluids such as saliva, urine, or blood from an infected person.

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: What Are The Common Symptoms?

- Fever

- Headache

- Breathing difficulties

- Cough and sore throat

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Muscle pain and severe weakness

Measles Outbreak In Disneyland: An International Traveler Gets Infected

Credits: iStock

Measles Outbreak in Disneyland: Health officials in Orange County sounded alarmed after they confirmed a recent measles case in a child who visited Disneyland last week. The Orange County Health Care Agency said on Saturday that the child was an international traveler who arrived at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). The child then went to Disneyland on Wednesday and that is what became the potential exposure window.

As per the health authorities there could be two possibilities of getting the disease:

- Goofy’s Kitchen in Disneyland Hotel, 10:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. on Wednesday

- Disneyland Park and Disney California Adventure Park, 12:30 p.m. to closing on Wednesday.

Health authorities said they are coordinating with Disneyland to contact employees who may have been exposed to measles. According to Orange County health officials, visitors present at the theme park during the identified period could develop symptoms between seven and 21 days after exposure.

Measles Spreads Easily, Experts Warn

Dr Danielle Curitore, a pediatrician at St Joseph Heritage Providence, explained NBC Los Angeles that measles is highly contagious and spreads through respiratory droplets.

“Very similar to these respiratory viruses, but even more so because it can be in a close setting and if that person with measles sneezes or coughs and transmits some respiratory droplets, you are exposed,” she said. “And that room that they’ve been in is also contagious for at least two hours after they left.”

Measles Outbreak In Disneyland: Vaccination Remains The Strongest Protection

Doctors emphasize that individuals who have received the measles vaccine, particularly the recommended two doses, are generally well protected against the disease. Those who have not been vaccinated face a significantly higher risk of infection.

Read: Measles Elimination Status In The US Is ‘Not Really’ At Risk, CDC Says As Cases Surge

“Your best protection is to be vaccinated, so if you’ve been vaccinated against measles and you’ve received your two doses of measles vaccine at any point, those are usually given in childhood but you do continue to be immune as you get older,” Dr Curitore added.

New Measles Cases Reported In Southern California

Health officials have confirmed at least five new measles cases in Southern California, prompting renewed warnings and surveillance. Authorities are closely monitoring the situation to limit further spread and identify potential exposure chains.

What Is Measles?

Measles, also known as rubeola, is an extremely contagious viral illness that typically causes high fever, cough, runny nose, red and watery eyes, and a characteristic rash that begins on the face and spreads downward across the body. It spreads through respiratory droplets and can lead to severe and sometimes fatal complications, including pneumonia and inflammation of the brain known as encephalitis.

Although it is preventable through the safe and effective MMR vaccine, measles remains a serious threat in many regions. There is no specific cure, and treatment focuses on managing symptoms, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Measles Outbreak In Disneyland: Common Symptoms To Watch For

Experts say measles symptoms often begin with signs similar to a common cold, including cough, congestion, and high fever. Some patients may also develop conjunctivitis.

“Sometimes it just starts out like the common cold cough congestion: high fever sometimes conjunctivitis can be part of it,” Dr Curitore said. “Then day three to five, you get that very classic measles rash, which usually starts on the face, center of the body.”

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited