- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Jharkhand Education Minister Ramdas Soren Suffers Brain Hemorrhage, Airlifted To Delhi

Credits: Canva

Jharkhand Education Minister Ramdas Soren remains in critical condition after suffering a severe brain injury following a fall in the bathroom at his residence early Saturday morning.

According to officials, the minister was initially admitted to a hospital in Jamshedpur, where doctors detected a blood clot in his brain. He was later airlifted to a private hospital in Delhi for more advanced treatment.

Health Minister Irfan Ansari confirmed the incident and said that Soren’s condition deteriorated rapidly after the fall. “Ramdas Soren’s health suddenly declined. He suffered a serious brain injury and internal bleeding in the brain. I have been in constant touch with his family and am monitoring the situation closely,” Ansari said.

Airlifted to Delhi for Advanced Care

After initial treatment in Jamshedpur, the decision was made to transfer the minister to Delhi for more specialized care. Former Union Minister and senior BJP leader Arjun Munda, who was present at Sonari Airport during the airlift, said, “I have spoken to the director of Delhi Apollo Hospital, and he has assured that treatment will begin as soon as the minister reaches. The doctors have diagnosed a brain hemorrhage due to a sudden increase in pressure. His condition is critical, but we are hopeful.”

On Saturday evening, the Delhi hospital issued a statement confirming that the minister was on life support and under the care of a multidisciplinary team of senior specialists. “A close watch is being kept on all vital parameters,” a spokesperson for the hospital said.

Understanding Brain Hemorrhage: What Happened to Ramdas Soren?

A brain hemorrhage, commonly known as a brain bleed, occurs when there is bleeding either inside the brain tissue or in the space between the brain and the skull. It is a medical emergency that can cause damage by increasing pressure on the brain, reducing oxygen supply, and killing brain cells.

Doctors categorize brain hemorrhages based on where the bleeding occurs:

Bleeding Outside Brain Tissue (Within Skull)

Epidural Hemorrhage: Occurs between the skull and the outer membrane (dura mater)

Subdural Hemorrhage: Bleeding between the dura mater and the arachnoid membrane

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Bleeding between the arachnoid and the innermost membrane (pia mater)

Bleeding Inside Brain Tissue

Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Bleeding within the brain’s tissues

Intraventricular Hemorrhage: Bleeding into the brain’s internal cavities that hold cerebrospinal fluid

In Soren’s case, doctors suspect a form of intracerebral or subdural hemorrhage, given the mention of clotting and pressure build-up.

Symptoms and Risks

Brain bleeds can come on suddenly and include symptoms like severe headache, nausea, vomiting, confusion, weakness or numbness (especially on one side of the body), vision problems, dizziness, seizures, slurred speech, and even coma. A particular warning sign is the so-called “thunderclap headache”, a sudden, intense pain that can signal a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

When not treated immediately, such bleeds can be fatal or lead to long-term neurological complications. In some cases, surgery is required to relieve pressure and remove clots.

What’s Next?

As of Saturday night, Ramdas Soren continues to remain on life support. No additional medical bulletins have been released since his transfer to Delhi, but officials have indicated that his condition is still being evaluated. “We are hoping for positive progress, but his condition remains critical,” said Arjun Munda.

Family members and close colleagues are at the hospital, and the Jharkhand government has said it will provide all necessary support for his treatment.

The political and public community has expressed concern and extended wishes for the minister’s speedy recovery. Further updates are awaited from the hospital and health authorities.

Legionnaire’s Disease Outbreak Kills 2 And Sickens 58 In New Your City- Know Symptoms And Risk

(Credit-Canva)

2 people have died and about 58 people have been diagnosed with Legionnaires disease in Harlem, New York. According to NYC Health statement, they are investigating a community cluster of Legionnaires' disease in Central Harlem.

They reported that the bacteria responsible for the outbreak, Legionella pneumophila, was found in 11 cooling towers. All of these towers have undergone the required cleaning and remediation.

Legionnaire’s disease is a type of of pneumonia that is caused by a bacteria called legionella, according to the Center of Disease Control and Prevention.

Acting Health Commissioner Dr. Michelle Morse is urging anyone in the affected areas who develops flu-like symptoms to seek medical attention immediately. Symptoms can include cough, fever, chills, muscle aches, or difficulty breathing. It is especially critical for high-risk individuals—such as those over 50, smokers, and people with chronic lung disease or weakened immune systems—to get care as soon as possible, as early treatment with antibiotics can be very effective.

How Legionnaire’s Disease Spreads?

Legionnaires' disease is caused by breathing in mist or water vapor that contains the Legionella bacteria. This bacteria thrives in warm water and can be found in various water systems, such as cooling towers, hot tubs, humidifiers, and large air-conditioning units. The disease cannot be spread from person to person.

To prevent the spread of Legionella, building owners and managers should follow a water management program. At home, you can take steps to prevent the growth of waterborne germs. For example, in vehicles, it's important to only use genuine windshield cleaner fluid instead of water, as Legionella can grow in the windshield wiper fluid tank.

Risk Factors for Legionnaire’s Disease

A 2014 review published in the Emerging Infectious Diseases journal showed that cases from 2002 to 2011 showed that the number of people getting Legionnaires' disease in New York City was on the rise, increasing by 230% during that time. The highest number of cases was in 2009, when the rate was 2.74 per 100,000 people—much higher than the national average of 1.15.

The study found a clear link between the disease and poverty. The areas with the highest poverty rates also had the most cases of Legionnaires' disease.

Additionally, people with certain jobs were more likely to get sick. For those who caught the disease in their community, there was a higher chance they worked in jobs like transportation, repair, protective services, cleaning, or construction.

What Are the Complications That Occur?

The disease was first identified in 1976 following an outbreak among people at an American Legion convention in Philadelphia.

If a doctor suspects pneumonia, they will perform a chest x-ray. To confirm if the cause is Legionella, other tests are needed, such as a urine test or a lab test using a sample of sputum or lung fluid. If you are diagnosed with the disease, the healthcare provider will report it to the local health department for investigation.

Legionnaires' disease is treated with specific antibiotics, and most cases can be cured successfully, especially with early treatment. Although healthy people usually recover, they often need to be hospitalized. Complications can include lung failure or even death. About 1 in 10 people who get the disease will die from complications. The risk of death is higher, about 1 in 4, for those who get the disease while in a healthcare facility.

WHO Reclassifies Hepatitis D As Carcinogenic, Warns Of 2-6% Rise In Liver Cancer Risk

Credits: Canva

The World Health Organization (WHO) has reclassified Hepatitis D as carcinogenic to humans, placing it in the same league as Hepatitis B and C—both already known for causing liver cancer. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), individuals living with both Hepatitis B and D face a 2–6 times higher risk of developing liver cancer than those infected with Hepatitis B alone.

This reclassification isn’t just a semantic shift. It’s a wake-up call. One that pushes governments, healthcare systems, and international partners to urgently act on viral hepatitis—a public health crisis hiding in plain sight.

Every 30 seconds, someone dies from liver cancer or severe liver disease caused by hepatitis. Hepatitis—especially the B, C, and D types—can silently wreak havoc on the liver, often going undiagnosed for years until irreversible damage sets in. Over 300 million people globally are currently living with chronic hepatitis infections, but the vast majority don’t even know they’re infected.

In 2022 alone, 1.3 million deaths were linked to complications from hepatitis-related liver cirrhosis and cancer. And yet, test and treatment coverage remains worryingly low.

What Makes Hepatitis D Especially Dangerous?

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is unique in that it cannot survive without Hepatitis B virus (HBV). It’s a co-infection that worsens outcomes dramatically. When someone already infected with HBV contracts HDV, the risk of liver inflammation, cirrhosis, and cancer accelerates significantly.

The IARC's move to declare HDV carcinogenic marks a pivotal moment. It helps shape global policy, medical research priorities, and public health campaigns focused on better diagnostics and innovative treatment.

WHO’s New Guidelines and Renewed Goals

In response to this new classification, WHO released comprehensive diagnostic guidelines for Hepatitis B and D in 2024. The agency is also closely monitoring emerging treatments for hepatitis D, which currently remain limited.

Hepatitis C remains the easiest to cure—with an average treatment time of 2 to 3 months. Hepatitis B, however, requires lifelong oral medications and ongoing monitoring. Hepatitis D treatments are still evolving, but effective disease control hinges on early testing, accurate diagnosis, and access to care. While there’s momentum, the reality remains mixed.

The number of countries with national hepatitis action plans rose sharply from 59 in 2020 to 123 in 2025—a good sign. Similarly, hepatitis B birth-dose immunization coverage increased to 147 countries in 2022, up from 138 but these gains are offset by glaring gaps:

Only 13% of those with Hepatitis B and 36% with Hepatitis C had been diagnosed by 2022

Treatment coverage was just 3% for Hepatitis B and 20% for Hepatitis C—well below WHO’s 2025 goals of 60% diagnosed and 50% treated

Just 27 countries have integrated Hepatitis C services into harm reduction centers, despite the known link with injectable drug use

Clearly, awareness and infrastructure haven’t kept up with the scale of the problem.

If current WHO targets are met by 2030, the world could prevent 9.8 million new infections and save 2.8 million lives but we’re not there yet. To close the gap, countries must:

- Expand hepatitis services into primary care systems

- Integrate testing and treatment with HIV and harm reduction programs

- Boost domestic investment in hepatitis programs as global donor support wanes

- Ensure access to affordable medicines and diagnostics, especially in low- and middle-income countries

And just as critically—reduce the stigma surrounding hepatitis testing and treatment

As WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus put it, “Every 30 seconds, someone dies from a hepatitis-related severe liver disease or liver cancer. Yet we have the tools to stop hepatitis.”

WHO isn’t working alone. The organization has joined forces with Rotary International and the World Hepatitis Alliance to boost local and global awareness campaigns. This multi-stakeholder approach underlines the need for government support, civil society involvement, and community leadership in the fight to eliminate hepatitis.

Efforts are underway to scale hepatitis services within existing healthcare platforms. Currently, 80 nations have integrated hepatitis into primary healthcare; 128 have folded hepatitis into HIV programs. These integrations make the most sense both financially and logistically, especially in countries grappling with strained health resources.

Understanding the Hepatitis Alphabet

Hepatitis A: Spread through contaminated food or water; usually resolves without lasting damage

Hepatitis B: The world’s most common liver infection; can become chronic and life-threatening

Hepatitis C: Spread through blood contact (e.g., shared needles); highly treatable but often undiagnosed

Hepatitis D: Only affects those with hepatitis B; now classified as carcinogenic with much higher cancer risk

Hepatitis E: Often resolves on its own, but can be dangerous in pregnancy

Among these, B, C, and D pose the highest risk of chronic infection, cirrhosis, and cancer.

The WHO’s reclassification of Hepatitis D as carcinogenic isn’t just a scientific update—it’s a call to arms. One that highlights the need to shift from reactive care to preventive action.

The tools exist, the data is clear. What’s missing is the political will, public awareness, and resource allocation to turn this silent killer into a preventable, treatable condition—no matter where someone lives.

If countries act now—boldly and collaboratively—millions of lives can be saved. And that’s a global health win the world can’t afford to miss.

Air Quality Health Index Explained: Why India’s AQI Needs An Overhaul And Include Death Risk

Credits: Canva

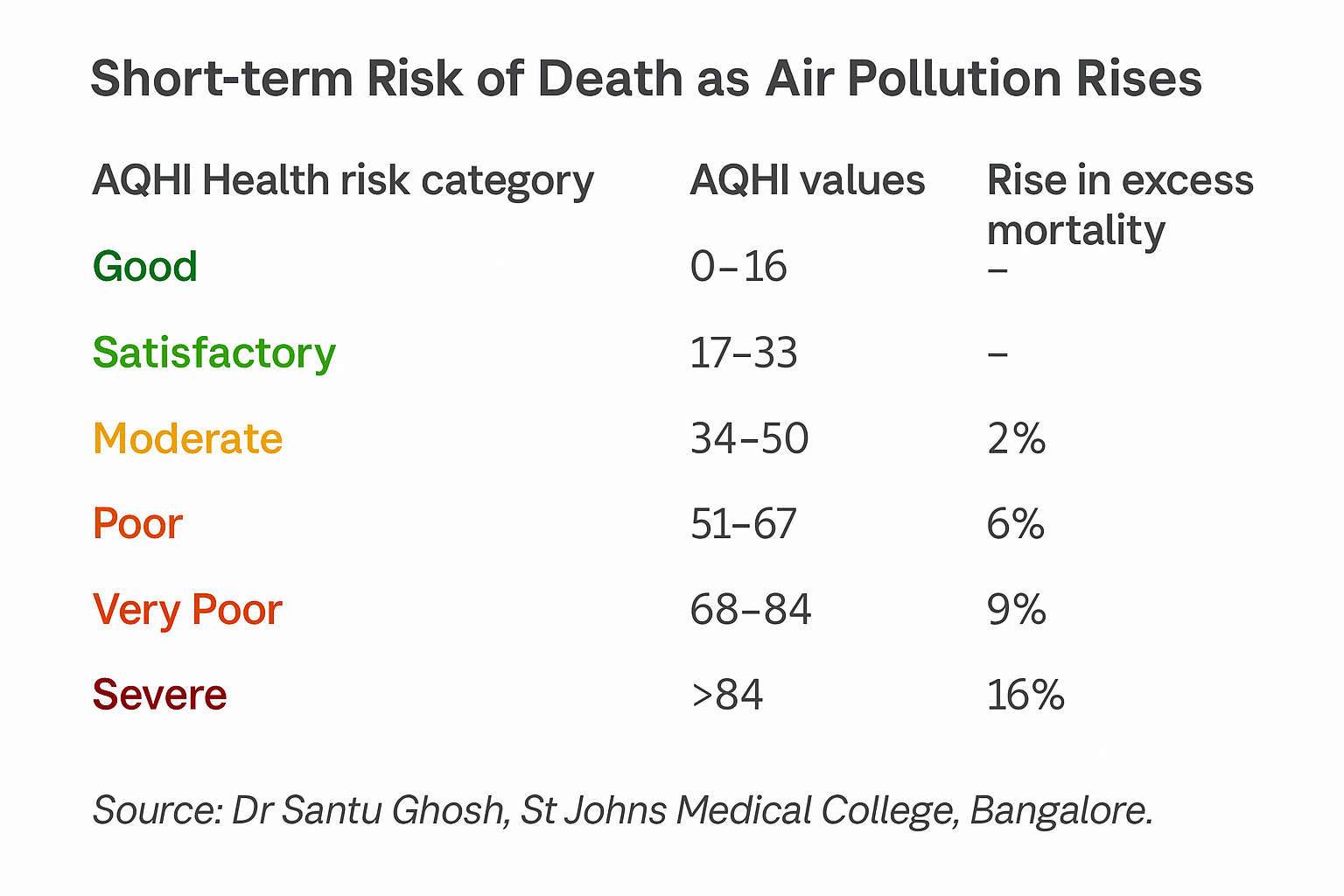

We often hear about Delhi’s "very poor" air days, but what does that really mean for your health? A new study, published in IOP Science, titled: A framework for city-specific air quality health index: a comparative assessment of Delhi and Varanasi, India, says it may mean a lot more than just coughing, breathlessness or a minor discomfort. In fact, on some days, it could mean a higher risk of death.

India’s current Air Quality Index (AQI), launched in 2015, was designed to simplify pollution levels and make it easy for people to understand the quality of the air they breathe. But a group of researchers now argue that this national index is outdated and dangerously vague when it comes to the actual health risk, particularly, the short-term risk of premature death.

Their recommendation? Replace the one-size-fits-all AQI with a more precise, city-specific Air Quality Health Index (AQHI) that includes the risk of excess mortality. This, they say, will allow both the public and policymakers to take air pollution far more seriously.

India's Air Quality Has Already Crossed WHO Limits

India’s worsening air quality is not just falling short of domestic health warnings, it is also regularly violating global safety standards.

ALSO READ: India Air Pollution Levels Surpass UN's Safety Standards

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), India’s air pollution levels consistently surpass safe thresholds, posing a grave public health threat. This is not just a concern for Delhi, although it remains one of the world’s most polluted capitals. The issue extends far beyond its borders.

Dr. Maria Neira, Director of WHO’s Department of Environment, Climate Change and Health, recently commented on this worrying trend. “There is a study which shows that we always focus on New Delhi when it comes to pollution, but I am afraid it is almost all of India where WHO standards on AQI are not implemented,” she said.

Dr. Neira warned that while being slightly off WHO norms is still problematic, many Indian cities now drastically exceed safe levels. The solution, she said, lies in stronger political commitment to clean air initiatives and faster implementation of existing policies.

40 Extra Deaths on a Single 'Severe' Pollution Day

According to the new study, published on 22 July, this year, led by Dr Santu Ghosh from St John’s Medical College in Bengaluru, a severe pollution day in Delhi could lead to 16% higher mortality. In simple terms, if Delhi records an average of 250 deaths in a day, a severe air day may result in 40 additional deaths.

That figure isn’t a vague long-term statistic, it reflects the immediate health impact of pollution. And yet, the current AQI doesn’t communicate this. A severe pollution reading today only warns that it "affects healthy people and seriously impacts those with existing diseases."

By contrast, the proposed AQHI categorizes air days based on the short-term increase in excess mortality. Even a ‘moderate’ air quality day, according to this new index, comes with a 2 percent rise in daily deaths, and this risk increases as pollution worsens.

Air Pollution: The India Problem

India’s air pollution is not just a seasonal or a regional issue. It is a year-round crisis that impacts vast sections of the population, especially in densely populated urban centres.

Several regions across the country routinely record AQI values far beyond safe limits set by both Indian authorities and international health agencies. The WHO warns that even brief exposure to high levels of pollutants can trigger serious health issues, something that millions of Indians face daily.

How AQHI Works and Why It’s Different

Unlike the AQI, which uses a 0 to 500 scale, the AQHI operates on a simpler 0 to 100 range. More importantly, it’s tailored to each city using local data on pollution levels and mortality rates.

The authors analyzed air pollution and mortality data from two cities: Delhi and Varanasi. Both were chosen for their political and public health relevance, Delhi being the national capital and Varanasi being the Prime Minister’s constituency, notes the study.

The AQHI makes a strong case that even the same pollutant levels affect cities differently.

For instance, if the PM2.5 level is 120 micrograms per cubic metre (a serious pollution level), the AQI might show 300 for both Delhi and Varanasi. But the AQHI, based on local health data, would show 46 for Delhi and 64 for Varanasi.

In AQHI terms, Delhi’s reading would be ‘moderate,’ while Varanasi’s would be ‘poor’, reflecting a real difference in public health impact.

Air Pollution Doesn’t Just Affect the Lungs

The WHO also notes that the main pathway of exposure to air pollution is through the respiratory tract, and that breathing in polluted air leads to inflammation, oxidative stress, immune suppression, and even cellular mutations throughout the body.

This can damage multiple organs, including the lungs, heart, brain, and more. WHO categorises air pollution as a risk factor for all-cause mortality, as well as for specific diseases such as stroke, ischaemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), lung cancer, pneumonia, and even cataract. Pregnant women and children are especially vulnerable to its effects.

Why the Current AQI Falls Short

India’s AQI uses health advisories from the US Environmental Protection Agency due to a lack of Indian studies when it was first launched. The 2015 document that introduced it even acknowledges this limitation. Since then, more local data has become available, but the AQI has not been updated.

The AQI also does not mention mortality risk in any of its categories. At most, it notes minor breathing discomfort or effects on sensitive groups. But research shows that air pollution is the second leading risk factor for non-communicable diseases in India. It is directly linked to heart attacks, strokes, and respiratory diseases, all of which can become fatal quickly, especially in older adults or those with pre-existing conditions.

What Can Be Done, Suggest Researchers

Dr Sagnik Dey from IIT Delhi, one of the authors, compares this to tobacco: "With smoking, the blame can be put on the individual. But with air pollution, it’s a public issue, the government has to step in."

One major challenge is access to mortality data, which is held by the Ministry of Health and the National Centre for Disease Control. However, researchers argue that once this data is made available, generating AQHI cut-offs for hundreds of Indian cities would take only a few months and cost very little.

Making Air Warnings Harder to Ignore

The AQI has become familiar in India over the past decade, even joked about by stand-up comics. But there’s little evidence that people or local authorities take its warnings seriously.

By including death risk, the AQHI could serve as a more effective tool. The aim is not to replace the AQI completely, but to enhance it so that people understand the real health consequences of the air they breathe.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited