- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Many Vegans Miss Out On Key Amino Acids Despite Getting Enough Protein, Study Reveals

Credit: Canva

YourA new study has found that while many long-term vegans consume enough total protein daily, a significant number still fall short of essential amino acids, raising concerns about protein quality in plant-based diets.

Conducted by a team of nutritionists from Massey University in New Zealand, the research analysed the diets of 193 vegans using four-day food diaries. The team used data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the New Zealand FoodFiles database to estimate amino acid intake from various plant-based foods. Their findings, published in the journal PLOS One, shed light on the challenges vegans face in achieving complete protein nutrition.

According to the study, around 75% of participants met their total daily protein needs. However, only about half reached the required intake for two crucial amino acids—lysine and leucine. These amino acids are classified as "indispensable" because the human body cannot produce them on its own and must obtain them through diet.

“Meeting adequate total daily protein intake in a vegan diet does not always guarantee a high protein quality diet,” the researchers warned. “Simply considering total protein intake without evaluating protein quality may lead to an overestimation of nutritional adequacy among vegans.”

Lead researchers Bi Xue and Patricia Soh emphasized the importance of including a diverse range of plant foods to meet the full spectrum of amino acid needs. While the body can synthesize many amino acids, nine must be sourced directly from food—making dietary balance crucial, especially in vegan diets.

The study pointed to legumes, nuts, seeds, and soy products as valuable sources for boosting lysine and leucine intake. These plant-based options can help vegans meet both their total protein requirements and maintain the right amino acid profile necessary for overall health.

“Achieving high protein quality on a vegan diet requires more than just consuming enough protein,” the team noted. “It also depends on the right balance and variety of plant foods to supply all the amino acids in the quantities our body needs.”

The researchers concluded by calling for further studies to explore effective strategies for improving amino acid intake in vegan populations. As more people adopt plant-based lifestyles, understanding how to maintain both protein quantity and quality is becoming increasingly important for public health.

Do you want a headline suggestion or social media blurb for this article?

Two Species Of Disease-Carrying Mosquitoes Detected in UK Amid Rising Climate Risks

Credits: Canva

Amid the ongoing Covid-19 scare in the UK, in another news, two species of disease-carrying mosquito have been also found there. These two species are now being found as a result of climate change, scientists too have warned against the same.

Aedes aegypti, also known as the Egyptian mosquito, and Aedes albopictus, also known as the (Asian) tiger or forest mosquito, both known for carrying diseases like yellow fever, dengue, chikungunya, Zika and dirofilariasis have been detected in surveillance traps set by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA). This was revealed in the UKHSA peer-reviewd study on invasive mosquito surveillance.

The Egyptian mosquito eggs were detected in a freight storage facility near London's Heathrow Airport, in September 2023- and tiger mosquitoes were detcted in August 2024. This will be the first time that the tiger mosquitoes have been detected since 2019, at a motorway srvice station in Kent.

The study published in research journal PLOS Global Public Health, reported the findings were lead by UKHSA and the Centre for Climate and Health Security.

What Has Changed Now?

Historically, both these species were limited to subtropical and tropical regions, however, among the populations established in southerns and central Europe, the mosquitoes have shown its ability to survive in temperate climates.

Rising temperature is said to be one of the major reasons for incursion of invasive species. This has put new populations at risk of disease transmission.

The authors of the study said, "While there is currently no evidence that Ae. albopictus or Ae. aegypti are widely established in the UK, without timely action, the UK faces the risk of invasive mosquito populations becoming established... proactive measures enhance resilience against emerging vector borne disease risks."

Call To Action

In addition to monitoring at ports and transport hubs across England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the UKHSA has also set up traps in the Kent marshes—considered an ideal spot for mosquitoes to settle due to its warm, wet conditions.

The UKHSA has also run Mosquito Recoding Scheme (MRS). This is a citizen-science project that receives and identifies mosquitoes submitted by members of public, including in response to nuisance biting incidents. Between 2005 and 2021, 286 reports of mosquitoes were submitted to the MRS, all of which were native UK species.

The aim of the scheme is to detect unusual or invasive species of mosquito, so prevention tactics could be put to use.

Collin Johnson, the lead author of the study and a senior medical entomologist at the UKHSA, said for the 2023 and 2024 discoveries: "Each detection triggered enhanced local surveillance and control measures, and the fact that no further specimens were found suggests these were isolated incursions."

"The collaborative efforts between UKHSA, local authorities and landowners were key to rapidly mobilising and preventing the establishment of invasive mosquitoes," he said.

Almost 100 People On Board Royal Caribbean Get Infected By Norovirus

Credits: Canva

More than 90 passengers and crew aboard a Royal Caribbean cruise ship have fallen ill from Norovirus, as per the reports. This ship's final stop was Miami.

The outbreak on the Royal Caribbean was first reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The ship had departed San Diego on September 19. A total of 94 passenger and 4 crew members were "reported being ill during the voyage," noted the CDC. The main symptoms as per CDC was diarrhea and vomiting.

Other symptoms include muscle ach, abdominal pain, fever, or three or more loose sttols within 24-hour period. From a total of 1,874 passengers and 833 crew, as per the reports, only 4% of people on board were infected, confirmed CDC.

The crew on the ship has increased their cleaning and disinfecting procedures. Stool specimens from gasteointestinal illness have been collected for testing and have been isolated from those who are sick.

In a statement to USA TODAY, the Royal Caribbean said, "The health and safety of our guests, crew, and the communities we visit are our top priority. To maintain an environment that supports the highest levels of health and safety onboard our ships, we implement rigorous cleaning procedures, many of which far exceed public health guidelines."

The Independent reports that the cruise ship also consulted with the Vessel Sanitation Program (VSP), which is remotely monitoring the situation, including review of the outbreak, response, and sanitation procedures.

What Is Norovirus?

As per the CDC, it is a very contagious virus that causes vomiting and diarrhea. It is commonly called the 'stomach flu" or "stomach bug".

However, norovirus illness is not related to the flu. The flu is caused by the influenza virus. Norovirus causes acute gastroenteritis, an inflammation of the stomach or intestines.

Most people with norovirus illness get better within 1 to 3 days; but they can still spread the virus for a few days after.

What Are The Symptoms Of Norovirus?

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Nausea

- Stomach pain

- Fever

- Headache

- Body aches

- Dehydration: If you have Norovirus, you can feel extremely ill and dehydrated and the symptoms can show through decreased urination, dry mouth and throat, feeling dizzy when standing up, crying with few or no tears, unusual sleepiness or fussiness.

Who Is At Risk?

- Anyone can get infected and sick with norovirus.

- People of all ages are affected during norovirus outbreaks.

- Genetic factors can partly determine your likelihood of infection.

- Raw oysters and other filter-feeding shellfish may contain viruses and bacteria that cause illness or even death.

- Eating raw shellfish puts anyone at risk of contracting norovirus.

- Children under 5, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems are more likely to develop severe infections.

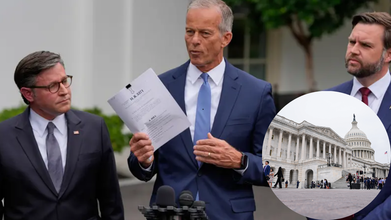

US Government Shutdown: What Does It Mean For Health Services?

Credits: AP

The US government shuts down at midnight confirmed Associated Press. The Vice President JD Vance said, "I think we're headed to a shutdown because the Democrats won't do the right thing," after a meeting where Congressional Democrats refused to give Republicans the votes they needed to pass a short-term funding agreement. The Democrats have demanded overhauls to Medicaid cuts and extensions to health care tax credits, something Republicans wish to stay out of.

House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries said that Republicans are "divorced from reality". He said, "They just wanted to kick the health care problem down the road."

What Does US Government Shutdown Mean For Health Services?

During a shutdown, only 59% of employees would be working at the Department of Health and Human Services. The rest are to be furloughed, meaning to be discharged from their job.

This means, out of the 47,257 employees who would be kept during the shutdown, only 35,000 would be continued to paid, while 12,000 would work without pay. Around 32,460 Health and Human Services (HHS) employees will be discharged from their work.

For the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), only 36% of employees would work, with 15% without pay, also reported by ABC News. At the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 86% employees would continue to work, with 19% without pay.

What it means for safety guidelines? The FDA's Animal Drugs and Foods Program "would end pre-market safety reviews of novel animal food ingredients for livestock, thus be unable to ensure that the meat, milk, and eggs of livestock are safe for people to eat; activities would be limited to those that address imminent threats to the safety of human life".

The National Institutes of Health would also come down to 24% of employees.

Will Medicare and Medicaid Continue During The US Government Shutdown?

Federal spending's biggest portion which is considered 'mandatory' will remain untouched, including payments by Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid.

While government officials say that payments won't be affected, related services could, however, slow down, including receiving replacement cards and benefit verification services.

This could also threaten around 7 million low-income women and their children who relied on programs like the Women, Infants. and Children (WIC), a US federal program that provides nutritious foods, nutrition education, and referrals to healthcare and social services for low-income pregnant and postpartum women, infants, and children up to the age of 5, who are at nutritional risk.

Ali Hard, who is the policy director for the National WIC Association told ABC News that if a shutdown continues for more than a week, WIC may begin to run out of funds.

Why Is The US Government Shutting Down?

The main crux of it could be the disagreement in the health policies. For the extended funding, which would only be possible through cuts in Medicaid, the Senate voted 55-45 on the measure, which has left Republicans five votes short of 60 vote threshold.

President Donald Trump on this said, "They (Democrats) want to give health care to illegal immigrants, which will destroy health care for everybody else in our country."

Previously it happened during the 2018-2019 shutdown, which lasted for 35 days.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited