- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Mounjaro Price Hike: Here's All That You Need To Know About This Weightloss Drug

Credits: Canva

From September, Eli Lilly will raise the UK price of its diabetes and weight-loss drug Mounjaro by as much as 170%. The US pharmaceutical giant says the increase will align UK costs with those in other developed nations and address “pricing disparities.”

The NHS will not be affected for now. The price surge is aimed at private patients and providers, who often negotiate discounts behind closed clinic doors. But for those paying out of pocket, the jump is steep, the highest monthly dose will soar from £122 to £330, while lower doses will rise by 45 to 138 per cent.

For many, this is more than a wallet shock. It could mean rethinking whether to continue treatment, especially since Mounjaro is often taken long term to maintain results. With so much at stake, here’s a closer look at what the drug does, who it’s for, and the benefits and risks to consider.

What is Mounjaro?

Mounjaro, the brand name for tirzepatide, is an injectable medication, notes Diabetes UK, and is approved in the UK for type 2 diabetes and, more recently, for obesity. It is part of a newer class of drugs that not only control blood sugar but also promote significant weight loss.

Unlike earlier medications such as Ozempic and Wegovy, both of which were based on semaglutide, Mounjaro works by activating two hormone receptors: GLP-1 and GIP, at the same time. This “dual agonist” approach appears to produce greater weight loss than single-receptor drugs.

How Does it Work?

Mounjaro increases levels of natural hormones called incretins. These hormones help the body release more insulin when needed, reduce glucose production by the liver, and slow digestion so you feel fuller for longer.

The result is a two-pronged effect:

Better blood sugar control in people with type 2 diabetes

Reduced appetite and calorie intake leading to weight loss

In clinical trials, people taking the highest dose (15 mg weekly) lost up to 21 per cent of their body weight. That’s on par with some bariatric surgeries, but without the invasive procedure.

Who Can Take Mounjaro?

For type 2 diabetes

Adults aged 18 and over who have not been able to control blood sugar with other medications, or who cannot tolerate them due to side effects or other conditions.

Typically prescribed if the person also has a BMI of 35 kg/m² or higher with obesity-related health issues, though exceptions exist for those with lower BMIs in certain ethnic groups or specific medical needs.

For obesity

In England and Wales: Recommended for people with a BMI of at least 35 kg/m² and related health conditions, including type 2 diabetes. Lower thresholds apply for some ethnic groups.

In Scotland: Available for people with a BMI of at least 30 kg/m² plus one obesity-related condition.

The Benefits

Significant weight loss that can improve or reverse obesity-related health problems

Improved blood sugar control in people with type 2 diabetes

Once-weekly dosing with a pre-filled pen for convenience

May reduce risk of complications from diabetes, though more research is ongoing for cardiovascular benefits

The Risks and Side Effects

Like other drugs in its class, Mounjaro can cause:

- Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation, indigestion

- Risk of low blood sugar if taken with insulin or certain other diabetes drugs

- Possible risk of high blood sugar if insulin doses are cut too quickly

- In animal studies, an increased risk of thyroid tumors, whether this applies to humans is still unknown

Long-term safety data is limited since the drug is relatively new. Some people may also regain weight if they stop taking it.

Cost and Access Challenges

On the NHS, Mounjaro is free for those eligible under treatment guidelines, but rollout is gradual due to costs and support service limitations. Access for weight loss alone is prioritized for those with the highest clinical need.

Private prescriptions vary in cost and availability. After the September price hike, the financial burden will be significant for many patients, especially since ongoing treatment is often required to maintain benefits.

Life Without the Jab

If the higher cost puts Mounjaro out of reach, lifestyle changes can still deliver meaningful results. Strategies that mimic some of its effects include:

- Eating high-protein meals to promote satiety

- Choosing high-fibre foods to slow digestion

- Limiting ultra-processed foods that spike blood sugar

- Regular physical activity to improve insulin sensitivity

15 States Sue Trump Administration Over Revised Vaccine Schedule

Credits: iStock

15 US states sued President Donald Trump led administration after the Department of Health and Human Services led by Health Secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr. revised vaccine schedule that led to coverage fall from 17 to 11 diseases for children. These 15 states are led Democrats and on Tuesday, they announced suing the Trump administration over unscientific grounds of releasing a new vaccine schedule.

The lawsuit has been filed by a coalition of 14 attorneys general and the governor of Pennsylvania. They have asked the courts to nullify the administration's decision to reduce the number of diseases children are routinely immunized from 17 to 11.

The lawsuit also challenges "the unlawful replacement" of members of the federal Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, who recommend vaccines for Americans. The lawsuit names the Department of Health and Human Services and Health Secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr as defendants. It also names the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and its acting director, Dr Jay Bhattacharya.

Read: CDC Vaccine Schedule: Coverage Falls From 17 to 11 Diseases For Children

15 States Sue Trump Administration Over Revised Vaccine Schedule: What Do The States Want?

In a news briefing on Tuesday, Rob Bonta, attorney general of California said, "H.H.S. Secretary R.F.K. Jr. and his C.D.C. are flouting decades of scientific research, ignoring credible medical experts, and threatening to strain state resources and make America’s children sicker.” Bonta continued, "The fact is, vaccines save lives and save our state’s money."

The lawsuit also notes that the administration's revised vaccination schedule was unscientific and relied instead on comparisons to countries that are different than the United States.

Kris Mayes, attorney general of Arizona, as reported by The New York Times said that the latest vaccine schedule "copies" Denmark's recommendation, where the country already has a nationalized health care and the population is fraction of that of the US. "Copying Denmark’s vaccine schedule without copying Denmark’s health care system doesn’t give families more options — it just leaves kids unprotected from serious diseases."

Also Read: Wegovy And Ozempic Will Cost Less In 2027, Novo Nordisk Slashes Weight Loss Drugs Prices By Half

15 States Sue Trump Administration Over Revised Vaccine Schedule: What Is The Revised Vaccine Schedule?

On January 5, 2026, the federal health officials led by RFK Jr. announced that the new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), vaccine schedule will include routine shots for 11 diseases for children. This is down from 17 diseases, which were earlier included.

Under the revised schedule, vaccines for a limited number of diseases remain universally recommended for children. These include protection against measles, polio, and whooping cough, which are still considered essential routine immunizations.

Vaccines No Longer Recommended for All Children

The most controversial change is the narrowing of recommendations for several common childhood vaccines. Immunization against the following illnesses is now advised only for high-risk children or after consultation with a health care provider:

- Hepatitis A

- Hepatitis B

- Meningococcal disease

- Rotavirus

- Influenza

- Respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV

Covid-19 vaccination has also shifted to a consultation-based recommendation rather than routine use for all children.

This means shots that were once automatically given at set ages, including at birth, during infancy, and in adolescence, may now depend on individual medical discussions rather than standard guidance.

Wegovy And Ozempic Will Cost Less In 2027, Novo Nordisk Slashes Weight Loss Drugs Prices By Half

Credits: iStock

Wegovy and Ozempic will cost less by January 1 of 2027 as manufacturer Novo Nordisk announced that the prices will be cut in half. The manufacturer said that the popular GLP-1 weight loss drugs will be as much as 50 per cent.

Wegovy and Ozempic Will Cost Less In 2027: How Cheap Can You Get Your Weight Loss Drugs For?

- The list price of Wegovy injections and the new Wegovy pill will be cut in half

- Ozempic injections will be cut by 35 per cent

The manufacturer noted that this cut applies to all doses and the semaglutide tablet Rybelsus will now cost $675 a month. Rybelsus has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to reduce the risk of heart attacks in those with diabetes.

Read: Doctor Explains Why Weight Loss Drugs Like Ozempic Are Truly A Medical Breakthrough

In a statement to PEOPLE, Jamey Millar, Executive Vice President, US Operations of Novo Nordisk Inc. said, "There are more than 100 million people living with obesity and over 35 million with type 2 diabetes and, for some, list price has been a real barrier to access and affordability."

Wegovy and Ozempic Will Cost Less In 2027: What Are The Current Price?

Wegovy injections and pills currently cost $1,349.02 a month, whereas Ozempic and Rybelus cost $1,027.51. These figures have been emailed to PEOPLE by Novo Nordisk.

Read: GLP-1 Drugs Don’t Just Curb Appetite; They Rewire the Brain, Shows Study

People with commercial insurance pay $25 a month, whereas those using cash pay between $149 to $499. Patients on Medicare will pay $274 per month.

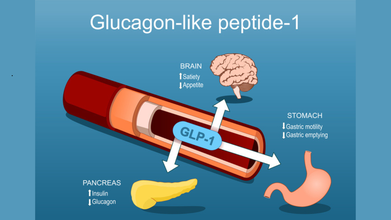

Wegovy and Ozempic Will Cost Less In 2027: How Do GLP-1 Weight Loss Drugs Work?

GLP-1 drugs mimic the action of the natural hormone GLP-1 to regulate blood sugar and promote weight loss. They work by increasing insulin release in a glucose-dependent manner, decreasing the liver's production of glucagon, and slowing down the emptying of the stomach, which helps lower blood sugar levels after a meal. They also act on the brain to suppress appetite and increase feelings of fullness, leading to reduced calorie intake.

Read: Zepbound Outperforms Other Weight Loss Drugs, More Details Inside

In people with type 2 diabetes, notes Harvard Health, the body's cells are resistant to the effects of insulin and body does not produce enough insulin, or both. This is when GLP-1 agonists stimulate pancreas to release insulin and suppress the release of another hormone called glucagon.

These drugs also act in the brain to reduce hunger and act on the stomach to delay emptying, so you feel full for a longer time. These effects can lead to weight loss, which can be an important part of managing diabetes.

In September 2025, WHO added GLP-1 drugs to its list of essential medicines, but only for treating diabetes, not for obesity alone. The new guideline extends that conversation, offering a more formal stance on their use in obesity management. The recommendations were developed by a committee of experts in obesity, pharmacology, and public health, following requests from several WHO member states. They also align with approvals already granted by regulators like the US FDA.

India Soon To Launch Nationwide Free HPV Vaccine For Adolescent Girls - Why Should Every Woman Consider It?

Credits: iStock

HPV Vaccine: India is planning to launch a free nationwide HPV or the Human Papillomavirus vaccination program to strengthen women's health and eliminate preventable cervical cancers in the country. Health and Me has also reported on the same. Government has also urged parents and guardians to come forward and ensure that their 14-year-old daughters are vaccinated against HPV.

Read: India to Soon Launch Free HPV Vaccine For Young Girls To Prevent Cervical Cancer

India Soon To Launch Nationwide Free HPV Vaccine: Why Should Every Girl Consider It?

Dr Asmita Dongare, a Pune-based consultant obstetrician and gynecologist writes on her website that cervical cancer is still one of the top causes of cancer-related deaths among Indian women. This is why every young woman must consider to get the vaccine, especially when the drive allows them to avail it for free.

HPV vaccination also provides up to 90 per cent protection against cervical cancer when administer before exposure. Studies have also shown that the vaccine is 97 per cent effective in preventing cervical cancer and related cell changes if given before the virus exposure.

Furthermore, the vaccine could prevent more than one type of cancer, notes the doctor, which includes:

- Vaginal and vulvar cancer

- Anal cancer

- Threat and head or neck cancer

- Genital warts

The vaccines have also shown to provide long-term protection with individuals monitored for at least 12 years who showed no evidence of weakened immunity. The vaccine creates antibodies and provide lasting protection against the virus.

Also Read: 15 States Sue Trump Administration Over Revised Vaccine Schedule

India Soon To Launch Nationwide Free HPV Vaccine: Who Can Avail It?

The vaccine is most effective when it is administered before exposure to HPV and before becoming sexually active. Young women aged 9 to 14 years show vaccine effectiveness of 74 to 93 per cent and this decreases with age.

- Girls aged 9 to 14 should get two doses of the vaccine in 6 to 12 months apart

- Women aged 15 to 26 years can get three doses in 0, 2, and 6 months apart

- Adults aged 27 to 45 must get it after consultation with their healthcare provider

India Soon To Launch Nationwide Free HPV Vaccine: Where To Get The Free Vaccine From?

The nationwide program, based on expert recommendations of the National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization (NTAGI), will target girls aged 14 years.

At 14, the HPV vaccine offers maximum preventive benefit, well before potential exposure to the virus.

"By prioritising prevention at the right age, the program is expected to provide lifelong protection and significantly reduce the future burden of cervical cancer in the country," the sources said.

Vaccination under the national program will be voluntary and free of cost.

The HPV vaccination will be conducted exclusively at designated government health facilities, including Ayushman Arogya Mandirs (Primary Health Centres), Community Health Centres, Sub-District and District Hospitals, and Government Medical Colleges.

The vaccine to be used is non-live and does not cause HPV infection. It is supported by more than 500 million doses administered globally since its introduction in 2006.

"India’s national program will use Gardasil, a quadrivalent HPV vaccine that protects against HPV types 16 and 18, which cause cervical cancer, as well as types 6 and 11. Strong global and Indian scientific evidence confirms that a single dose provides robust and durable protection when administered to girls in the recommended age group," the sources said.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited