- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Nag Panchami: Are We Killing Snakes by Feeding Them Milk?

Credits: YouTube

Today is Nag Panchami, a festival that worships snakes in India. The conventional way to worship snakes is by feeding them milk. But did you know that feeding milk to snakes might kill them? That too in a painful manner.

The Science Behind It

Snakes are reptiles that hunt and eat meat, mostly rodents, birds, and other small animals. Snakes lack the enzymes required to break down lactose, the sugar present in milk, in contrast to mammals. As a result, forcing milk into a snake's digestive system might cause serious problems. In fact, snakes are lactose intolerant, experts say that snakes fed milk may experience bloating, indigestion, and dehydration.In extreme cases, this can lead to the death of the snake.

Forest departments and wildlife experts have issued numerous warnings against this practice. For instance, in 2017 the Thane, Maharashtra, forest department issued a warning saying that giving milk to snakes is not only against nature but can be lethal. The department emphasised that these acts of devotion are cruel because they cause needless agony for the snakes.

Misconceptions and Myths

The idea that snakes consume milk is among the most widespread misconceptions about them. Stories from culture and religion that show snakes sipping milk tend to perpetuate this false idea. But milk isn't something that snakes look for to eat.Their action when dehydrated is not what is meant to be understood by the idea that they consume milk. A snake may swallow any liquid that is presented to it if it is extremely dehydrated, but this is a desperate move and does not mean that milk is a good food source for snakes.

Wildlife experts emphasise that these customs are not grounded in science, but rather in superstition. These actions hurt snakes and spread unwarranted fear and false information about these reptiles, according to the staff at Wildlife SOS, an organization devoted to the rescue and rehabilitation of wildlife.

Awareness and Education

Raising awareness and promoting education is crucial to stopping the dangerous habit of feeding milk to snakes. By dispelling the misconceptions about snakes and advancing knowledge of their nutritional requirements, we can help prevent needless injury to these reptiles. If you are reading this, then you can spread this information to people you know who might follow this custom. This is how awareness works.It is important to understand that, even while cultural customs are very important to us, they must change in tandem with scientific advancements to prevent harm from being done to the same creatures we wish to respect.

Vasai MBBS Student Saved A Fellow Passenger's Life On Goa-Mumbai Flight

Credits: Canva

A Vasai final-year MBBS student saved a fellow passenger in Goa-Mumbai Flight. As per a report by Lokmat Times, the incident took place on February 3 when a passenger on an Indigo flight that department from Dabolim Airport in goa at 3.50 pm started experiencing breathing difficulty. His condition worsened and he collapsed in the aircraft. This caused panic.

The cabin crew made an announcement asking if there were any doctors on board. Aryan Lolayekar, a final-year medical student from Mumbai's Vasai responded to the call. He was travelling on the same flight.

Lolayekar found that man's blood sugar levels had dropped significantly and that his heart rate had also slowed down. This caused him dizziness and led to loss of consciousness. Along with all this, the high altitude of the flight also posed a serious risk to his life.

The final-year medical student began administering first aid and used the emergency oxygen cylinder on board. He provided artificial respiration to stabilize the patient. In aa few minutes, the patient's condition improved.

The flight had a duration of 45 minutes. After the aircraft landed safely in Mumbai, IndiGo staff shifted the passenger to a hospital for further treatment.

Lolayekar's prompt actions earned him applauds and praises. Speaking on the incident, he said that he initially felt anxious when he saw the passenger's condition. However, he relied on his medical training to act quickly. He said that the timely use of oxygen proved to be crucial during the time.

How Does CPR Help In Emergency Cases?

Lack of CPR training is a significant barrier for most. While many know that CPR can save lives, not many are trained in doing that. One must be trained to carry out CPR safely.

A study found that only 18% of people had received CPR training within the last two years, which is crucial for skill retention. Although many people have received CPR training at some point in their lives, the skills may be outdated or forgotten.

To address this, some US states have made CPR training mandatory for high school graduation, and countries like Denmark and Norway have implemented similar requirements. In the U.S., CPR courses are widely available online and in-person, and many take just a few hours to complete. These courses teach individuals the basics of CPR, which involves performing chest compressions at a rate of 100 to 120 per minute and a depth of at least two inches.

Also Read: Know What to Do: CPR and AED Basics for Everyone

What IS CPR?

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is an emergency treatment that's done when someone's breathing or heartbeat has stopped.

The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends starting CPR by pushing hard and fast on the chest. The pushes are called compressions. This hands-only CPR recommendation is for both people without training and first responders notes AHA.

Position the person:

- Lay the person flat on their back on a firm, level surface.

Start chest compressions (hard and fast):

- Place the heel of one hand in the centre of the chest, between the nipples. Put your other hand on top and interlock your fingers. Keep your elbows straight and position your shoulders directly above your hands. Push straight down at least 2 inches (5 cm) at a steady rate of 100–120 compressions per minute—about the beat of “Stayin’ Alive.” Allow the chest to fully rise between compressions.

Give rescue breaths (if trained):

- After 30 compressions, tilt the head back and lift the chin to open the airway. Pinch the nose shut, seal your mouth over theirs, and give two breaths, watching for the chest to rise. If it doesn’t, reposition the head and try again.

Continue CPR:

- Keep alternating 30 chest compressions with 2 rescue breaths until emergency help arrives, an AED is ready to use, or the person shows signs of movement.

Catherine O'Hara Cause Of Death Is Pulmonary Embolism; She Also Had Rectal Cancer

Credits: Wikimedia Commons

Catherine O'Hara's cause of death is pulmonary embolism, confirmed medical examiner. She died on January 30 in a Los Angeles hospital, at the age of 71. The Schitt's Creek star also had blood clot in her lungs and her death certificate also listed rectal cancer as the long term cause of death.

She had been receiving treatment for the cancer since March 2025.

Catherine O'Hara Cause Of Death: What Is Pulmonary Embolism?

As per the National Health Service (NHS), a pulmonary embolism is a life-threatening condition that happens when a blood vessel in the lungs is blocked by a blood clot.

The common symptoms may include:

- Difficulty in breathing

- Chest pain

- Cough up blood

The blood clot starts in a deep vein in the leg and travels to the lung in most cases. Rarely, the clot forms in a vein in another part of the body, noted Mayo Clinic. When a blood clot forms in one or more of the deep veins in the body, it is called a deep vein thrombosis or DVT.

Other symptoms of pulmonary embolism include:

- irregular heartbeat

- lightheadedness or dizziness

- excessive sweating

- fever

- leg pain or swelling, usually at the back of lower leg

- clammy or discolored skin

As per Cleveland Clinic, about a third of people with a pulmonary embolism die before diagnosis and treatment, highlighting the condition's severity.

Catherine O'Hara Cause Of Death: She Also Had Rectal Cancer

Catherine O'Hara also was battling rectal cancer, which had been a long-term health challenge for her. The diagnosis was kept private. As per TMZ and The Associated Press, the diagnosis was kept private with only close family and her medical team aware of the details. Her struggle with cancer was not widely known, which made her news of rectal cancer more shocking to her fans and many in the industry.

Rectal cancer is a serious and often aggressive disease. According to the Mayo Clinic and the American Cancer Society, it typically starts as abnormal growths known as polyps in the rectum and can require intensive treatment, including surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Colorectal cancer—which includes cancers of both the colon and rectum—remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths in the United States. This year, nearly 50,000 people are expected to be diagnosed with rectal cancer, while colorectal cancer overall is projected to claim around 55,000 lives nationwide.

Rectal cancer too can increase the risk of developing blood clots, making complications like pulmonary embolism, more common among cancer patients.

Catherine O'Hara Cause Of Death: She Was Born With A Rare Genetic Condition

Speaking in previous interviews, O'Hara revealed that she was born with a rare genetic condition called situs inversus. This means the organs are mirrored from their usual positions. Her heart, for instances, pointed to the right side of her chest, a condition known as dextrocardia. While this is a harmless condition, situs inversus could sometimes be associated with other complications.

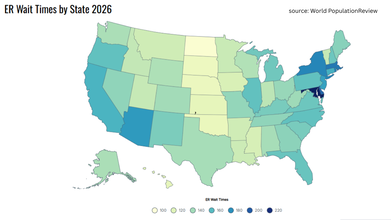

ER Patients in Massachusetts Wait 3+ Hours on Average, Third-Longest in the US

Credits: Canva

ER Patients in Massachusetts Wait: Any visit to hospital must be treat with uttermost urgency, especially when it is the visit to the ER. What is worse is waiting a long time to see a doctor or a medical team even during an ER visit. A new analysis by health insurance experts at Compare the Market finds that the US has the lowest number of hospitals, per capita, in the world, which means 1.84 hospitals per 100,000 citizens. This is what makes the waiting time longer.

This has placed US behind countries like Chile which has 1.85 hospitals per 100,000 citizens and Thailand with 1.89 hospitals per 100,000 citizens. According to the same analysis, South Korea ranks top with 7.38 hospitals per 100,000 citizens, followed with Japan with 6.64 hospitals per 100,000 citizens. Among the 54 countries evaluated in the analysis, the United States ranked 29.

ER Patients in Massachusetts: Longest Wait Hours In US

| US States | ER Wait Time (in minutes) |

| Maryland | 228 |

| Delaware | 195 |

| Massachusetts | 189 |

| Rhode Island | 185 |

| New York | 184 |

| Arizona | 176 |

| New Jersey | 173 |

| Connecticut | 166 |

| California | 164 |

| Illinois | 157 |

The top on the list was Maryland with 228 minutes, or almost 4 hours, followed by Delaware with 195 minutes.

ER Patients in Massachusetts: Long Wait Hours Leads To Death

There have been cases where long ER waits have led to patients' deaths in the US. A KKTV report from 2022 notes a 77-year-old North Carolina patient who went to New Hanover Regional Medical Center waited for more than 5 hours. The patient met with a triage at 8.43pm and was given an urgent designation, but was told to sit in the waiting room. Investigation revealed that she was not assessed until the next day at 8.am for her vitals to be taken. The woman was pronounced dead at 4.25am.

A Fortune report from 2025 interviewed an Illinois family who lost their father Bill Speer to ER boarding. Tracy Balhan, the daughter revealed that her father died after struggling with dementia. She took him to the emergency room at Endeavor Health's Edward Hospital in Chicago suburb of Naperville. However, Speer spent 12 hours in the ER.

An older report by EMS World from 2011, revealed a case of a Texas man who died after waiting for 16 hours for treatment in ER.

This is not just the case in the US, but a very recent case reported by Health and Me was of a 44-year-old Indian origin man, Prashant Sreekumar, who died at a Canadian hospital's ER after an 8-hour weight. His father, Kumar Sreekumar told the Global News that he was checked in at triage and then seated in the waiting room. When his father reached the hospital, he told him, "Papa, I cannot bear the pain." "It went up, up, and up. To me, it was through the roof," his father said. He was finally called for treatment after more than eight hours of wait." After sitting maybe 10 seconds, he looked at me, he got up and put his hand on his chest and just crashed," his father said.

ER Patients in Massachusetts: What Is ER Boarding?

Read: “Papa, I Can’t Bear the Pain”, Says Indian-Origin Man Who Dies After Eight-Hour ER Wait in Canada

ER boarding is a common term that is used to highlight the health care system's struggle which includes shrinking points of entry for patients seeking care outside of ERs and hospitals prioritizing beds for procedures insurance companies often pay more for, and for making patients wait long hours for ER visits.

1 in 6 visits to the ER in 2022 that resulted in hospital admission had a wait of four or more hours, as per an Associated Press and Side Effects Public Media data analysis.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited