Scientists Say A Type 1 Diabetes Cure May Be Close, Raising Hope for Life Without Insulin Shots

Credits: Canva

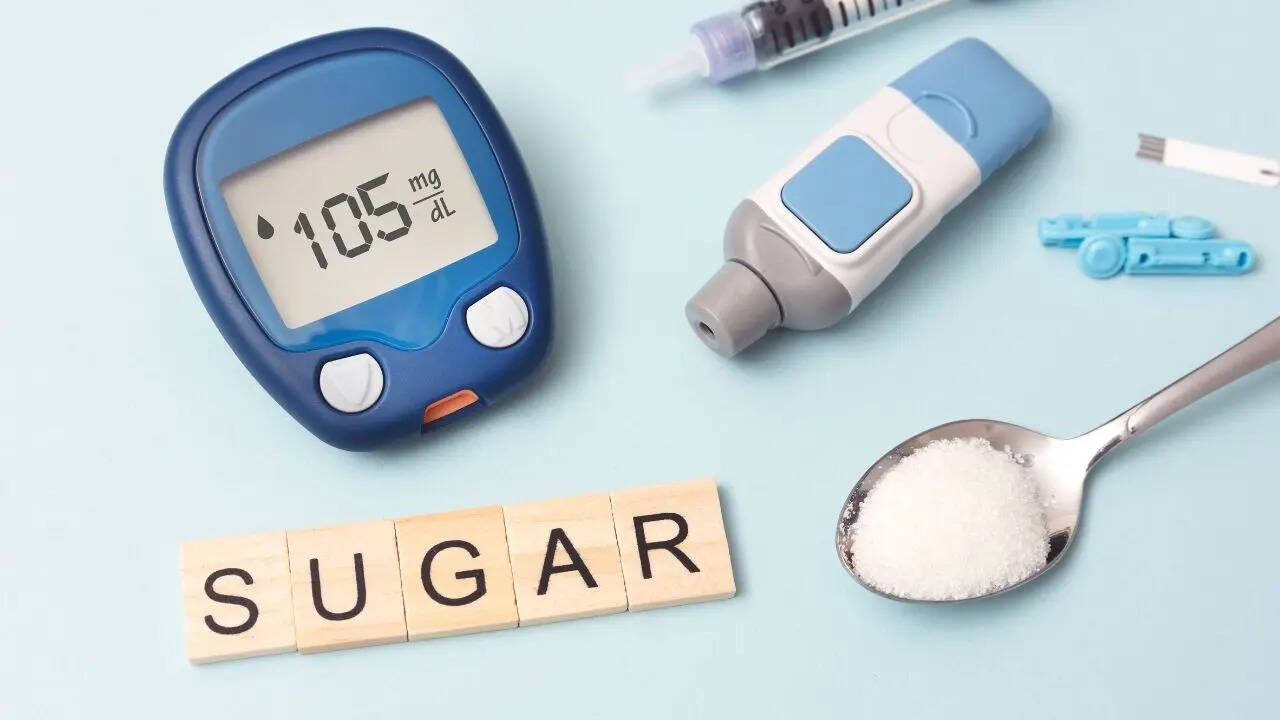

SummaryA new approach using stem cells to rebuild insulin-producing beta cells may help people with diabetes restore natural insulin production and reduce dependence on injections. Keep reading for more details.

End of Article