- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

This Age-Old Killer Is Spreading Fast, Why Super Typhoid Isn’t Just A ‘Poor Country’ Problem Anymore

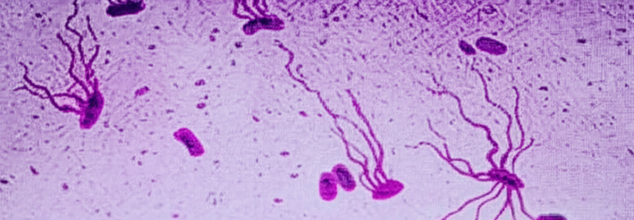

Representational

Typhoid fever is not the kind of illness most people in developed nations worry about. It's often written off as a disease of the past—something that plagued ancient societies before clean water systems and antibiotics. But here’s the thing: typhoid never went away. And now, it's evolving into something much more dangerous—something even modern medicine might not be able to stop.

A large genomic study published in The Lancet Microbe in 2022 has sounded the alarm. The bacterium responsible for typhoid, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (or S. Typhi), is rapidly acquiring resistance to nearly all antibiotics used to treat it. More disturbingly, strains resistant to multiple drug classes are spreading beyond their traditional strongholds in South Asia and appearing across continents—including in the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada.

This is no longer a regional concern. It’s a global one.

What is Super Typhoid?

The study involved sequencing over 3,400 S. Typhi strains collected between 2014 and 2019 from patients in India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh. The results were stark. Not only were extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strains of typhoid rising rapidly, but they were also outcompeting and replacing less resistant versions.

Also Read: From ADHD To Burnout: Why Modern Life Is Making You Sleepless, Anxious And Insomniac

XDR typhoid strains are already immune to several older antibiotics—ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. But here’s where it gets worse: many are now developing resistance to newer and more potent drugs like fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins, which until recently were mainstays of typhoid treatment.

Even the last reliable oral antibiotic—azithromycin—is showing signs of failure. The study found emerging mutations that could potentially render azithromycin ineffective. These haven’t yet converged with XDR strains, but scientists warn that it’s only a matter of time. If that happens, oral treatment options could become entirely obsolete.

For now, South Asia remains the epicenter of the crisis, accounting for about 70% of the global typhoid burden. But this doesn’t mean the threat is contained.

Researchers tracked nearly 200 instances of international transmission since the 1990s, most involving travel or migration. Typhoid "superbugs" have been detected in Southeast Asia, East and Southern Africa, and in wealthy nations where the disease was thought to be virtually eradicated.

“The speed at which highly-resistant strains of S. Typhi have emerged and spread is a real cause for concern,” said Dr. Jason Andrews, an infectious disease specialist at Stanford University who co-authored the study.

Why Is Treatment Is Failing?

If antibiotics are failing, what’s next? For starters, prevention. Experts say the most immediate and scalable solution lies in typhoid conjugate vaccines (TCVs). These vaccines offer strong, long-lasting protection and are safe for children as young as six months old. But access is patchy.

Pakistan became the first country to introduce TCV into its national immunization program in 2019—an urgent response to the first major outbreak of XDR typhoid that hit its population. Since then, the move has become a case study in how vaccination can cut off the disease at its roots.

India, Bangladesh, and Nepal have followed suit with pilot programs and localized rollouts, but global coverage remains far too low. Meanwhile, high-income countries have not prioritized TCV access at all, largely because typhoid isn’t seen as a domestic threat.

Antibiotic Resistance Crisis at Large

This typhoid crisis isn’t an isolated story. It’s part of a larger, systemic problem: antibiotic resistance is now one of the top global causes of death. A 2019 study published in The Lancet estimated that antimicrobial resistance was directly responsible for 1.27 million deaths worldwide, surpassing HIV/AIDS and malaria.

Typhoid is just the latest face of that threat. If azithromycin fails, intravenous treatments will be the only remaining option. This is not sustainable for low-resource settings, where typhoid is most rampant.

And as the S. Typhi genome continues to adapt, the search for novel antibiotics becomes more urgent but the global antibiotic pipeline is worryingly dry. Very few new drugs are being developed, and those that are rarely target neglected tropical diseases like typhoid.

How Globalization Makes It Everyone’s Problem?

COVID-19 reminded us how quickly a localized health threat can go global. Typhoid is no different. The bacteria travel with people—through tourism, immigration, and international trade.

The difference is: we already have tools to stop this. TCVs work. Better sanitation and access to clean water help. Public health messaging and travel guidelines can make a difference. But we’re not moving fast enough.

A recent Indian study estimated that vaccinating children in urban areas could reduce typhoid cases and deaths by up to 36 percent. That’s a significant dent—especially when combined with infrastructure upgrades and careful antibiotic stewardship.

What Happens If We Do Nothing?

If left unchecked, drug-resistant typhoid could become nearly impossible to treat in outpatient settings. That means more hospitalizations, more strain on health systems, more deaths—particularly among children in developing nations.

With around 11 million cases of typhoid annually, even a small increase in resistance could tip the balance into a major health crisis.

And if XDR strains gain resistance to azithromycin, we will be left with zero effective oral drugs, none. The path forward is clear—and urgent. Here’s what needs to happen:

- Expand global access to typhoid conjugate vaccines, especially in endemic regions.

- Invest in next-generation antibiotics that target typhoid and other neglected infections.

- Implement stricter regulations on antibiotic use in agriculture and medicine.

- Strengthen global surveillance systems to detect resistant strains early and contain outbreaks.

- Raise awareness that typhoid is not just a problem for the developing world.

Antibiotic resistance isn’t science fiction. It’s a biological reality. And typhoid is just one example of how quickly things can unravel when we underestimate an ancient enemy.

We can still turn the tide but only if we act with urgency and coordination. The warning signs are flashing red. Typhoid isn’t gone. It’s evolving. And this time, it may be deadlier than ever.

Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: All That You Need To Know About This Infection

Credits: iStock

Nipah virus outbreak in West Bengal has raised concerns in parts of Asia. This has also led some airports to implement precautionary health screenings. As of now, five infections have been reported from the state, including two nurses, a doctor, hospital staff and some patient. According to India's health ministry, 196 people are known to be in contact with the infected individuals, however, when tested, the results came out negative.

Nipah Virus Outbreak India: How Contagious Is This Disease?

Nipah virus is infectious and can spread from animals like bats and pigs to humans through bodily fluids or contaminated food. It can also pass between people through close contact, especially in caregiving settings. While it can spread via respiratory droplets in enclosed spaces, it is not considered highly airborne and usually requires close, prolonged contact for transmission. Common routes include direct exposure to infected animals or their fluids, consuming contaminated fruits or date palm sap, and contact with bodily fluids such as saliva, urine, or blood from an infected person.

Read: Nipah Virus Outbreak in India, Travelers Screened At Airports

People most at risk of Nipah virus are those who are more likely to come into close contact with infected animals or patients. This includes:

- Healthcare workers caring for Nipah patients, especially without proper protective equipment

- Family members and caregivers who have close physical contact with infected individuals

- People living near bat habitats, particularly fruit bat roosting areas

- Those who consume contaminated food, such as raw date palm sap or fruits partially eaten by bats

- Farmers, animal handlers, and slaughterhouse workers who work with pigs or other animals that can carry the virus

- Residents of outbreak-prone regions in India and Bangladesh, where Nipah cases recur

- People with weak immunity, who may develop more severe illness after infection

- Close, prolonged contact is the biggest risk factor. Casual contact in public spaces is far less likely to spread the virus.

What Is Nipah Virus?

As per the World Health Organization (WHO), Nipah virus infection is a zoonotic illness that is transmitted to people from animals, and can also be transmitted through contaminated food or directly from person to person.

In infected people, it causes a range of illnesses from asymptomatic (subclinical) infection to acute respiratory illness and fatal encephalitis. The virus can also cause severe disease in animals such as pigs, resulting in significant economic losses for farmers.

Although Nipah virus has caused only a few known outbreaks in Asia, it infects a wide range of animals and causes severe disease and death in people.

Also Read: Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: How Did It All Begin?

Nipah Virus Symptoms

- Fever

- Headache

- Breathing difficulties

- Cough and sore throat

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Muscle pain and severe weakness

Nipah Virus Outbreak: Origin

The original infection was first identified in September 1998 in Perak, Malaysia, which was followed by second and third clusters in the state of Negri Sembilan, notes a 2021 study that tracks the evolution of the virus. The cases were prominent in adult men who were in contact with swine. By March 1999, a cluster of 11 similar cases were identified in Singapore, mostly common in slaughterhouse workers, who were in contact with pigs imported from Malaysia.

Then appeared a new, distinct strain of Nipah virus with infection which was characterized largely by severe respiratory symptoms. In 2000-2001, Bangladesh and India were affected.

It was later revealed that due to the consumption of raw date palm juice, the infection developed. This is because bats also are carrier of the virus and they may bite into raw fruits or lick them, and consuming juice from such fruits could spread the infection. This was a common practice in Bangladesh and much of South Asia.

Donald Trump Alzheimer’s Speculation Rises After Niece Notices Worrying Sign

Credits: AP/Canva

Donald Trump's niece has suggested her uncle may be showing signs of Alzheimer's disease after noticing a concerning facial expression. Mary Trump, a well-known critic of her uncle who frequently speaks about him on her YouTube channel, has implied that he could have the degenerative condition, noting similarities to her late grandfather, who also suffered from Alzheimer's.

Donald Trump's Niece Says He May Have Alzheimer's

As per UK Express, Mary highlighted that she has seen resemblances to Fred Trump, Donald's late father and former real estate magnate, who battled Alzheimer’s before passing away more than 25 years ago in 1999 at the age of 93. Speaking last year, Mary recounted witnessing her grandfather’s decline and suggested that Donald sometimes doesn’t seem “oriented,” pointing to a particular look. Talking about her grandfather, she told New York Magazine: "One of the first times I noticed it was at some event where he was being honored. And I looked at him and saw this deer-in-the-headlights look, like he had no idea where he was."

In further remarks, Mary said she now notices what the publication described as “flashes” of her grandfather in her uncle when she sees him on stage, pointing out the same “deer-in-the-headlights” expression.

She added: "Sometimes it does not seem like he's aware of time or place. And on occasion, I do see that deer-in-the-headlights look."

Donald Trump Rejects Alzheimer’s Claim

Meanwhile, the former US President has rejected such claims, previously stating that he “aced” three cognitive tests and insisting there is no possibility of him having Alzheimer's disease.

In a conversation with the magazine, Trump also reflected on his father’s diagnosis: "He had one problem. At a certain age, about 86, 87, he started getting what do they call it?"

His press secretary, Karoline Leavitt, supplied the term for Trump, who referred to it as an “Alzheimer’s thing,” asserting that he did not “have it.” The health of the 79-year-old has been the subject of much public speculation recently, with observers noting bruises on his hands, what appear to be swollen ankles, and rambling speech.

However, in October last year, reports indicated that Trump had undergone a “routine yearly checkup” at the Walter Reed Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland.

His physician, Navy Capt. Sean Barbabella, stated in a one-page note: "President Donald J. Trump remains in exceptional health, exhibiting strong cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurological and physical performance."

What Is Alzheimer’s?

According to the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of dementia, a term used to describe a group of symptoms linked to progressive brain function decline. Memory problems are often one of the earliest signs, but as Alzheimer’s progresses, people may experience confusion, disorientation, difficulty with language and speech, and changes in behavior.

What Health Condition Has Trump Been Diagnosed With?

Earlier this year, the White House revealed that Trump has chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), a common vascular condition in which veins in the legs struggle to return blood efficiently to the heart. This disorder can result in swelling and discomfort in the legs.

On October 10, Trump made another visit to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. His spokesperson, Karoline Leavitt, described it as a “routine annual check-up,” despite it being his second visit to the facility in six months. Dr. Sean Barbabella, the White House physician, did not disclose details of any imaging or preventive tests conducted during the appointment but stated that Trump’s lab results were “exceptional” and his cardiac health appeared about 14 years younger than his chronological age.

On October 27, Trump mentioned that he had an MRI scan during a previous visit to Walter Reed. He claimed the results showed “some of the best reports for the age” and “some of the best reports they’ve ever seen,” though the lack of specifics has fueled continued speculation about his health.

Trump has also spoken about taking the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), a test designed to detect cognitive decline, but has described it as a “very difficult IQ test.” It is unclear whether another MoCA test was conducted during his October visit or if he was referencing the assessments he undertook in April 2025 or January 2018.

Nipah Virus Outbreak in India, Travelers Screened At Airports

Credits: iStock

Nipah virus outbreak has triggered screenings at the airport. After two cases were reported in India's West Bengal, concerns have sparked in many parts of Asia, and measures at airports have been tightened.

Thailand has begun screening passengers at three airports that handle flights from West Bengal. Nepal has also stepped up checks, screening arrivals at Kathmandu airport as well as at several land border crossings with India.

In West Bengal, five healthcare workers were infected earlier this month, with one reported to be in critical condition. Around 110 people who came into contact with them have since been placed under quarantine.

Nipah virus spreads from animals to humans and carries a high fatality rate, estimated to be between 40 percent and 75 percent. At present, there is no approved vaccine or specific treatment for the infection.

What Is Nipah Virus?

As per the World Health Organization (WHO), Nipah virus infection is a zoonotic illness that is transmitted to people from animals, and can also be transmitted through contaminated food or directly from person to person.

In infected people, it causes a range of illnesses from asymptomatic (subclinical) infection to acute respiratory illness and fatal encephalitis. The virus can also cause severe disease in animals such as pigs, resulting in significant economic losses for farmers.

Although Nipah virus has caused only a few known outbreaks in Asia, it infects a wide range of animals and causes severe disease and death in people.

Read: Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: How Did It All Begin?

During the first recognized outbreak in Malaysia, which also affected Singapore, most human infections resulted from direct contact with sick pigs or their contaminated tissues. Transmission is thought to have occurred via unprotected exposure to secretions from the pigs, or unprotected contact with the tissue of a sick animal.

In subsequent outbreaks in Bangladesh and India, consumption of fruits or fruit products (such as raw date palm juice) contaminated with urine or saliva from infected fruit bats was the most likely source of infection.

Human-to-human transmission of Nipah virus has also been reported among family and care givers of infected patients.

Nipah Virus Symptoms

- Fever

- Headache

- Breathing difficulties

- Cough and sore throat

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Muscle pain and severe weakness

Nipah virus outbreak in India has led to nearly 100 people being quarantined. India is facing Nipah virus cases and contagion every year now. Experts are now cautioning people against the zoonotic nature of the viral infection. Rajeev Jayavedan, the former president of Indian Medical Association, Cochin, told The Independent, that infection among humans are rare and caused by the accidental spillover due to human-bat interface, which means consumption of fruits that may have been infected by bats. “This is more likely in rural and forest-adjacent areas where agricultural practices increase contact between humans and fruit bats searching for food,” he said.

Health and Me previously reported on how doctors are now advising people to be cautious while eating food. Speaking to TOI, Dr Aishwarya R, Consultant, Infectious Diseases at Aster RV Hospital advised people against eating certain food, including fruits fallen from trees, unpasteurized date palm sap and any other fruits without washing. The doctor explained that this infection can spread with infected animal who could bite fruits and spread the virus through their saliva.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited