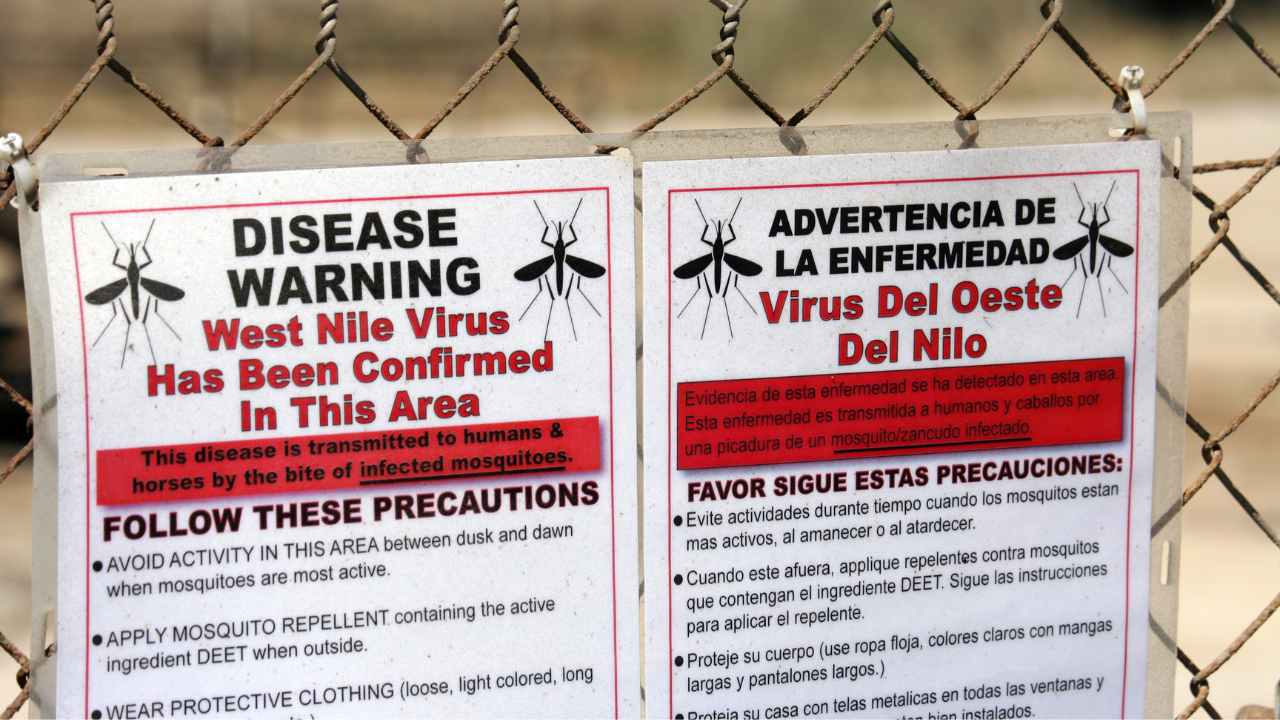

West Nile Virus Isn't Over Yet, New Cases In US On Rise

Credits: Canva

SummaryWest Nile virus cases are rising across the U.S., with 771 reported in 39 states and nearly 500 severe neuroinvasive cases. Ohio has seen six infections this season. Experts warn the risk continues until the first frost, urging precautions like repellents, long sleeves, and removing standing water to prevent mosquito breeding.

End of Article