- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Bird Flu Cases In US: Could It Trigger The Next Global Pandemic?

Bird Flu Cases In US: Could It Trigger The Next Global Pandemic?

The specter of bird flu, or Avian Influenza A (H5N1), is once again looming, this time in a more ominous leap from animals to humans. As the threat level at the moment remains low, the experts are watching closely its new species and regional interventions, raising alarms about its potential to mutate into a more dangerous form. With cases flying under the radar largely, it becomes crucial to understand the trajectory of the virus, its potential risks, and preparedness challenges.

The H5N1 bird flu has evolved from being an avian problem to infecting mammals and, occasionally, humans. Recent outbreaks have affected poultry, dairy cows, and humans in several U.S. states, including California, Colorado, Michigan, Missouri, Texas, and Washington. Infections among farmworkers—mostly those milking cows or cleaning barns—have been reported, with symptoms such as eye redness, fever, sneezing, and sore throat.

Testing of 115 dairy workers from Michigan and Colorado revealed that 7% had antibodies against the H5N1 virus, indicating previous exposure. Half of these individuals reported no illness, suggesting that some infections may result in mild or even asymptomatic cases.

The behavior of H5N1 also raised red flags globally. In Cambodia, a hybrid strain between two subtypes of the virus has emerged, with at least three deaths and displaying mutations that enhance airborne transmission among mammals. These developments underscore the virus's ability to adapt, making vigilant monitoring critical.

Several U.S. federal agencies are working in tandem to address the outbreak:

-The USDA leads from the animal health side by coordinating with the FDA and CDC.

-The FDA ensures safety for milk, dairy products, and feed intended for animals in order to safeguard public health.

-The CDC tracks human infections, tests potential cases, and tracks virus movement.

Despite these efforts, challenges remain. Testing gaps, limited surveillance in some states, and flaws in diagnostic tools mean many cases may go undetected, leaving communities vulnerable.

Risk of Mutation and Pandemic Potential

While human-to-human transmission of H5N1 has not been documented, the possibility remains a primary concern. Historical data paints a grim picture: since the virus's discovery in 1997, over 900 reported human cases have occurred globally, with a mortality rate exceeding 50%. Cambodia recently reported ten cases, including two fatalities, attributed to a more virulent strain.

If H5N1 mutates further to attain sustained human-to-human transmission, it will unleash a pandemic of catastrophic proportions. The US federal government has started the process of vaccine stockpiling, but the present level of supply is alarmingly grossly inadequate.

The United States has less than five million doses of H5N1 vaccines, which would be enough to cover only 2% of the population. Manufacturing contracts also have been signed to produce an additional 10 million syringes by 2025, though this timeline may be too slow in the face of a rapidly evolving virus.

The technology behind these vaccines is also antiquated. Most are produced in a slow and inflexible, century-old egg-based process. No licensed mRNA-based flu vaccine—a technology that proved so valuable during the COVID-19 pandemic—is available to add to this preparedness.

According to an immunologist, Dr. Vasso Apostolopoulos, genetic makeup could influence virulence for H5N1. Mutations in genes critical for such functions as hemagglutinin, helping viruses get inside the cells, and another that helps in enhancing replication, have been discovered recently. This may mean that genetic mutations may further enhance its capacity to induce severe disease.

Lessons to Learn from COVID-19

The similarity between H5N1 and early COVID-19 is unnerving. Like SARS-CoV-2, H5N1 can quietly spread until a tipping point is reached. The world saw how quickly a virus could immobilize societies before vaccines were widespread. Still, current preparedness for a bird flu pandemic is still woefully insufficient.

It took almost a year to bring forward the first COVID-19 vaccines, in which millions lost their lives due to the virus. Experts believe that H5N1 will not present humanity with the flexibility to adapt slowly. The delayed response of the world towards the spread of a future H5N1 pandemic may be devastatingly slow unless advanced vaccine technologies are prepared proactively and investment in it is made.

How to Mitigating the Bird Flu Threat?

To reduce the spread of H5N1, robust responses are required:

1. Public health agencies should increase testing for H5N1 in humans and animals, especially in high-risk environments like farms.

2. Accelerating the development and stockpiling of mRNA-based vaccines could provide a faster, more adaptive response.

3. Countries must share data, resources, and expertise to monitor and contain the virus.

4. Protective measures in case of exposure to infected animals for farmworkers are essential, such as wearing personal protective equipment and health checkup on a regular basis. H5N1 bird flu is a stark reminder that the line between preparedness and vulnerability is thin.

The risk at this moment is low, but the mutation and the historical lethality it holds require a proactive attitude. The lessons from COVID-19 highlight the price paid for underestimation of a virus's potency. The next pandemic will not be if, but when. Whether we rise to the challenge or repeat past mistakes will therefore define the impact of H5N1 on global health.

Why Hypertension Is Soaring Stroke Risk, Death In Young Indians

Credit: Canva

Hypertension or high blood pressure, a major risk for stroke, is preventable and treatable. Yet it accounts for about 14 per cent of cases of stroke among young adults aged below 45 years.

High blood pressure can be defined as the increasing pressure in blood vessels marked as 140/90 mmHg or higher.

Uncontrolled hypertension can burst or block arteries that supply blood and oxygen to the brain, causing a stroke.

A recent study by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) found that hypertension (74.5 percent) was the most common risk factor for stroke and related deaths (27.8 percent) and significant disability (about 30 per cent) across India.

“Blood vessel walls can be damaged through uncontrolled high blood pressure, making them prone to blockage or rupture. The good news is that hypertension is preventable through regular monitoring, reduced intake of salt, exercise stress control, and medication when required,” Dr. Rajul Aggarwal, Director - Neurology, Sri Balaji Action Medical Institute, Delhi, told HealthandMe.

How Does Hypertension Increase The Risk Of Stroke?

Chronic high pressure forces the brain to compensate, leading to vessel remodeling, narrowing, and eventually rupture or clotting.

The ICMR study reported that ischemic stroke accounted for 60 percent of cases.

The experts explained that in the case of ischemic stroke, high blood pressure damages artery walls, fostering plaque buildup (atherosclerosis) or allowing clots to form and block blood flow to the brain.

On the other hand, with hemorrhagic Stroke, constant strain caused by high blood pressure weakens artery walls, causing them to burst or leak blood into the brain. This can result in severe damage or life-threatening emergencies.

“When blood pressure stays high for years, it slowly strains the blood vessels -- nothing dramatic at first, which is why people ignore it. The arteries become stiff and fragile, sometimes narrowing, sometimes tearing,” Dr. Gunjan Shah, Interventional Cardiologist, Narayana Hospital, Ahmedabad, told HealthandMe.

"This makes clots or bleeding in the brain more likely, leading to ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, even in people who otherwise feel perfectly fit and busy with daily life," Dr. Shah added.

Importance of the ‘Golden Hour’ In Stroke Care

In stroke-related cases, the golden hour -- referred to as the critical first 60 minutes after symptom onset -- is very much critical. Early medical treatment during the window can prevent death risk as well as boost health outcomes.

However, the ICMR study, published in the International Journal of Stroke, showed that just 20 percent of patients arrived in the hospital after 24 hours of the onset of symptoms.

Dr. Aggarwal said treatment within the first 60 minutes can significantly reduce the brain damage and improve survival as well.

“In a stroke, time moves very differently. Brain cells begin getting damaged within minutes when blood flow stops. If someone reaches the hospital quickly -- within the golden hour -- we have a real chance to restore circulation and limit disability. Recognising symptoms early and not waiting at home can truly change how well a person recovers,” added Dr Shah.

How Can Hypertension And Stroke Be Prevented?

Hypertension is a modifiable disease, and the risks can be reduced by:

- Cutting down and managing stress

- Checking blood pressure regularly

- Treating high blood pressure

- Eating less salt

- Staying active

- Managing stress

- Sleeping properly

- Avoiding tobacco

Dr Shah said that many young patients delay care because they feel fine, but taking medicines on time and correcting lifestyle early can prevent serious problems later.

Where You Get Your Rabies Shot Matters: Doctor Explains Why Rabies Vaccines Should Not Be Given In Buttocks

Credits: Canva and screengrab from Instagram

Dr Srivanjani Santosh, Pediatrician, Social Activist and First Aid trainer, who had earlier spearheaded the ORS campaigned for eight years, urging FSSAI to ban the misuse of the term 'ORS' on non-WHO=standard sugar drinks, has once again shared an important health video on rabies vaccination. Dr Santosh shared that if any mammal, including dog, cat, horse, cow, buffalo, monkey or bat scratch or bit a person, they must be vaccinated with rabies shot.

She also pointed out something many miss: the location of administering the rabies shot. In her video she urged people to not get the shot administered in buttocks, and to only get it on their shoulders or thighs. She also claimed that many clinics and hospitals, despite knowing this fact, are administering rabies vaccination on buttocks.

Also Read: Hangover Star Ken Jeong's Wife Beats Stage 3 Breast Cancer

Why Does Location Of Administration Matter In Rabies Shot?

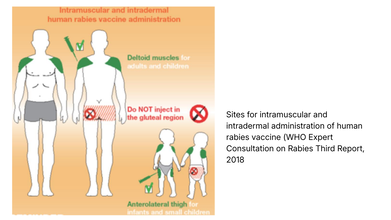

The World Health Organization (WHO) strongly recommends that rabies vaccines must be injected into the deltoid region, which is the upper arm or near the shoulder region in adults.

In small children, the WHO notes that deltoid region, as well as anterolateral area of the thigh muscle, which is also the upper thigh works.

WHO notes that like any other injections, rabies vaccine should not be given in the gluteal region, that is the buttocks, because of low absorption due to the presence of adipose or the fat tissue.

This video comes at the time when a case of a Birmingham woman losing all her limbs to dog's lick has made headlines all over the news. Health and Me also reported on the same.

Read: Woman Loses All Her Limbs After Getting Sepsis From Dog Lick

Health and Me spoke to Dr. Rakesh Pandit, Senior Consultant & HOD, Internal Medicine at Aakash Healthcare, who further explained, that as per guidelines by the WHO, the rabies vaccine should not be given in the buttocks as they have a heavy layer of fat. The body might not properly absorb the vaccine if it is injected into this fat instead of the muscle, which could result in a vaccine failure.

"A vaccine failure in case of rabies is like a death sentence because the disease is one hundred percent lethal once it shows the signs. The injection site for the vaccine depends on the patient's age; older children and adults must receive the vaccine in the upper arm or shoulder, while infants and toddlers must receive it in the thigh. The vaccine must also be administered with the right needle length to reach the required depth," he said.

Dr Pandit further elaborated, "The place of administering the vaccine (arm or thigh, subcutaneous or intramuscular) has an effect on the immune response, speed at which the vaccine is absorbed, pain and the risk of side effects." He said, "Some vaccines give best results when given in muscle for better immunity. Other vaccines may need subcutaneous administration. When given at the correct site, the vaccines ensure maximum effect, safety and reduced local reactions like swelling."

Read: 36% Of Rabies Death Comes From India: This Is What You Should Do After A Dog Bite, Explains Doctor

What Should One Keep In Mind While Getting A Rabies Shot?

Dr Mule points out that even when there are minor scratches, without bleeding, you must get a rabies shot. "Rabies can be contracted through broken skin. Such exposures still require medical evaluation and, in most cases, rabies vaccination."

What Should One Do Immediately After Being Bitten Or Scratched?

- Wash the wound immediately for at least 15 minutes with soap and running water

- Apply an antiseptic such as povidone-iodine

- Do not apply home remedies like turmeric, chili or oil

- Seek medical care promptly for rabies vaccination and possible immunoglobin

Dr Mule points out that the rabies vaccine should be started as soon as possible. "Ideally within 24 hours of a bite or scratch. However, even if there is a delay of days or weeks, vaccination should still be started immediately as rabies has a variable incubation period," he says.

The temperature of the vaccine matters. "Rabies vaccines are temperature-sensitive and must be stored between 2°C and 8°C. Exposure to heat or freezing can reduce vaccine potency. Poor cold-chain maintenance is a known reason for vaccine failure in rare cases," points out the doctor.

Dr Mule points out that the vaccine should be given intramuscularly in the deltoid or upper arms for adults, as gluteal or buttock injections could lead to inadequate absorption and reduce effectiveness.

Study Links Throat Infection To Sudden Skin Inflammation, Psoriasis

Credit: Canva

A simple strep throat infection, can trigger sudden skin inflammation, leading to psoriasis, particularly in children and young adults, according to a study.

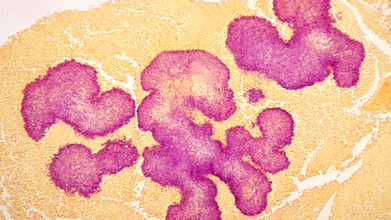

Researchers from the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden showed that a strep throat infection caused by the Group A Streptococcus (GAS) bacterium, can trigger guttate psoriasis by altering the behavior of key immune cells. Guttate psoriasis is an often sudden-onset form of psoriasis with small, red, "drop-shaped" scaling spots on arms and legs.

While neutrophils -- the most common type of immune cell -- are the first immune cells to respond to GAS infection, the study showed that during a streptococcal infection, the immune cells behavior changes depending on their environment.

Notably, among people with guttate psoriasis, the neutrophils presented with antigens -- fragments of pathogens that signal and guide other immune cells -- get accumulated. Once accumulated, the immune cells activated the T cells, leading to inflammation, explained the researchers in the paper, published in the journal eBioMedicine.

"Doctors have long known that strep throat can precede guttate psoriasis, but the biological explanation has been unclear," said Avinash Padhi, first author of the study and Research Specialist at the Division of Dermatology and Venereology, at Karolinska.

"Our findings suggest a link between infection and skin inflammation through the accumulation of antigen-presenting neutrophils in patients' skin," Padhi added.

How Cells Shape Immune Response

The team analyzed receptor–ligand interactions -- the molecular signals cells use to coordinate immune responses to examine how neutrophils interact with other cells.Magdalini Lourda, senior author of the study and senior research specialist at the Department of Laboratory Medicine, noted that the "results challenge the traditional view of neutrophils as simple first-line defenders".

The findings show that the neutrophils play "a wider role in shaping immune responses, which may be important when designing future treatments."

How Was The Study conducted?

Using single-cell technologies, the team analyzed blood and skin samples of patients with guttate psoriasis. This enabled the researchers to examine thousands of individual immune cells in detail.To find how neutrophils work in psoriasis, the blood neutrophils from psoriasis patients were compared with those from healthy individuals. Blood neutrophils from patients with severe strep-related lung inflammation were also compared.

What Is Guttate Psoriasis?

Guttate psoriasis is a distinct form of acute-onset psoriasis. It is an inflammatory skin disease characterized by the sudden appearance of red, scaly, and smaller skin lesions widespread over the body.

The condition typically follows an infection, most commonly tonsillitis caused by Group A Streptococcus (GAS). Adolescents and young adults are the most affected. It accounts for about 2 per cent of all cases of psoriasis.

Genetics, environmental triggers, such as an upper respiratory tract infection, and the onset of an inflammatory condition in a distant organ are the major risk factors.

The condition may be diagnosed by skin biopsy, throat swab culture, and blood tests.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited