- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Diagnosed At 7, Bedridden At 25, This Woman’s Battle With A Chronic Skin Condition Led To Something Inspirational

Credits: Youtube/@ThePatientstory

When Alana was just seven, she was diagnosed with psoriasis — a chronic autoimmune condition that left painful, scaly patches across her skin. By 25, her diagnosis expanded to include psoriatic arthritis, a debilitating condition that affects the joints and often hides in plain sight. Her story, however, is not just one of suffering — it’s a powerful testament to resilience, self-acceptance, and the ongoing battle for awareness around invisible illnesses. In a world obsessed with flawless appearances, Alana’s candid journey from being overmedicated to embracing a holistic lifestyle offers a much-needed spotlight on the realities of chronic skin conditions and the strength it takes to advocate for one’s body.

“I remember scratching until my skin bled,” Alana recalls. “Doctors didn’t know what was happening. My childhood became a blur of nurse’s office visits and topical creams.” Misunderstood and often misdiagnosed in its early stages, psoriasis is an autoimmune condition where the skin cells build up rapidly, forming scales and itchy, dry patches. In Alana’s case, the progression was swift and emotionally jarring.

By the age of nine, Alana was already on a restrictive anti-inflammatory diet. While other kids enjoyed sweets and processed snacks, she studied ingredient labels, became intimately familiar with holistic remedies, and avoided sugar like it was poison. “My mom would say, ‘Psoriasis feeds on sugar,’” she shares. “So while my siblings had Oreos, I had the sugar-free health store version—if I was lucky.”

Navigating adolescence with visible skin symptoms brought its own trauma. “Middle school was brutal,” Alana confides. “I wore arm socks and stacked bracelets just to hide my arms. I’d wear wigs to hide my scalp. There were days I couldn’t even look at myself in the mirror.”

Like many who live with psoriasis, Alana also faced the psychological burden—body image issues, bullying, and feelings of shame that often go unseen in clinical narratives. “No one talks about the depression that comes when you’re in remission. Your skin is clear, but emotionally, you’re still healing.”

What is Psoriatic Arthritis?

At 25, just as Alana thought she had a handle on her condition, she experienced her first flare-up of psoriatic arthritis—another autoimmune condition closely tied to psoriasis. “I couldn’t walk for a week. I was terrified,” she remembers. “But my dad, who has it too, told me—‘This is how it starts. Buckle up.’”

Psoriatic arthritis is marked by inflammation of the joints, often developing years after skin symptoms appear. It adds a layer of physical disability to an already taxing disease and affects nearly 30% of people with psoriasis. For Alana, it meant another upheaval—mentally, physically, and emotionally.

Psoriatic arthritis is a form of arthritis that affects individuals with psoriasis, a condition that causes red, scaly patches on the skin. While psoriasis typically develops first, in some cases, joint issues appear before skin patches or simultaneously. The condition is marked by joint pain, stiffness, and swelling, which can affect any part of the body, including the fingers, toes, and spine. Psoriatic arthritis varies in severity, with disease flare-ups alternating with periods of remission.

Over the years, Alana tried it all—steroids, topical creams, biologics, cortisone injections. “Steroids helped, but the more I used them, the thinner and more fragile my skin became. It got worse in the long run.” Like many patients, she experienced the rollercoaster of temporary relief followed by long-term setbacks.

A biologic medication gave her a temporary reprieve from flare-ups, allowing her to enjoy a rare period of skin clarity. “It was my party girl era. My skin was clear, I felt normal, but the side effects were awful—migraines, nausea, and daily pills.”

Ultimately, the fear of long-term side effects led Alana to quit biologics in 2018. With that decision came a resurgence of symptoms—but also, a shift in mindset.

Alana decided she would no longer hide. “I thought, so many people have skin conditions. Why should I be ashamed?” She began sharing her story on social media. To her surprise, her vulnerability resonated. “One day a brand reached out for a skincare campaign. Next thing I know, I’m on billboards.”

For someone who once layered bracelets to hide her skin, it was a full-circle moment. “If I could go back and show my 7-year-old self—the goth little girl in all black—these pictures, I’d tell her, you’re going to be okay. You’ll help others one day.”

Symptoms of Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic disease that progressively worsens over time, though there are periods when symptoms improve or temporarily disappear. The key symptoms include:

Swollen Fingers and Toes: Often described as painful, sausage-like swelling in the fingers and toes.

Foot Pain: Pain in the areas where tendons and ligaments attach to bones, such as the Achilles tendon and the soles of the feet.

Lower Back Pain: This is caused by spondylitis, which inflames the joints between vertebrae and in the spine-pelvis region.

Nail Changes: Psoriatic arthritis may cause nails to form small dents, crumble, or separate from the nail beds.

Eye Inflammation: Uveitis causes eye pain, redness, and blurry vision, and if untreated, it can result in vision loss.

In 2019, Alana made a dramatic switch to a vegan lifestyle. “I left a dermatologist appointment in tears because I didn’t want to go back on meds. That day, I cut everything—dairy, meat, processed foods—cold turkey.” She admits now that she wasn’t fully informed. “I dropped to 100 pounds. I was frail. I didn’t know how to nourish my body properly.”

Still, her holistic journey taught her what worked—and what didn’t. Through trial and error, cookbooks, and community forums, she carved a path rooted in listening to her body. “There’s no one-size-fits-all with psoriasis. What helps one person might trigger another.”

Today, Alana continues to live with both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. She still faces flare-ups, but she’s better equipped mentally, emotionally, and socially. “This disease doesn’t define me. It’s part of my story, not the whole story.”

Her message to others? “Don’t let shame win. Find your community. And know that healing isn’t just about clear skin—it’s about acceptance, too.”

Alana’s journey highlights the often-hidden aspects of chronic skin conditions—misdiagnosis in childhood, the emotional toll of visible symptoms, the physical limitations of psoriatic arthritis, and the long, non-linear road to healing. As public conversations around autoimmune diseases and skin positivity grow, stories like hers are critical reminders that healing is just as much about self-love as it is about science.

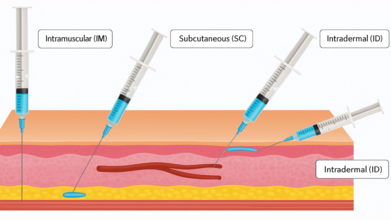

IV Drip, COVID-19 Shot And Ozempic: How Different Injections Enter The Body In Different Ways

Credits: Canva and AI generated

Injections are one of the most direct and effective ways to deliver medications, nutrients, or fluids into the body. Unlike oral medicines, which must first pass through the digestive system, injections allow a substance to enter the bloodstream, muscle, or tissue directly, leading to faster or more controlled absorption.

There are several types of injections, but four are most widely used in healthcare practice: intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intraosseous. Each has its own purpose, method, and site of administration.

Intravenous (IV) Injections

Intravenous injections deliver medication straight into a vein, allowing for rapid absorption and immediate action. Because the bloodstream is accessed directly, this type of injection is considered the fastest way to introduce drugs or fluids into the body.

Common Uses

IV injections or infusions are frequently used in:

- Providing fluids and electrolytes to treat dehydration

- Administering local or general anesthesia before surgery

- Delivering pain relief medications in emergency rooms

- Blood transfusions and iron supplementation

- Nutrition for severely malnourished patients

- Chemotherapy for cancer treatment

- Monoclonal antibodies for infections such as COVID-19

- Injecting contrast dye before imaging tests

Sites of Injection

Typical IV sites include veins on the back of the hands, forearms, or inside the elbow. In infants, doctors may use veins on the scalp or feet.

Intramuscular (IM) Injections

Intramuscular injections deliver medication into the muscle tissue, which has a rich blood supply that helps the drug absorb quickly, as noted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (CDC) guidelines.

Common Uses

- Most vaccines, such as flu shots

- Antibiotics like penicillin or streptomycin

- Corticosteroids for inflammation or allergic reactions

- Hormones such as testosterone or medroxyprogesterone

- Medications for patients unable to take oral drugs

Sites of Injection

Healthcare professionals usually administer IM shots in:

- The upper outer thigh muscle

- The deltoid (shoulder) muscle

- The hip area

Doctors generally avoid injecting into the buttock due to the risk of damaging the sciatic nerve.

Subcutaneous (SC) Injections

Subcutaneous injections are given into the fatty tissue just beneath the skin and above the muscle. They use a smaller needle to ensure the medication enters the fatty layer rather than muscle tissue. Unlike muscles, fatty tissue contains fewer blood vessels, which means the body absorbs medication more slowly—making it useful for drugs that require steady, prolonged release.

Common Uses

- Insulin for diabetes management

- Blood thinners like heparin

- Vaccines such as MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) and chickenpox

- Pain control medications in palliative care (e.g., morphine, fentanyl)

- Fertility medications and biologics such as Dupixent

Sites of Injection

Typical SC injection sites include:

- The outer or back part of the upper arm

- The front or outer side of the thigh

- The belly (at least a few centimeters away from the navel)

Subcutaneous injections are relatively less painful and carry a lower risk of infection. They are often preferred for patients who need to self-administer medication at home, such as those managing diabetes.

Intraosseous (IO) Injections

Intraosseous injections are less common but extremely valuable in emergency medicine. They involve puncturing the bone marrow with a specialized needle to deliver drugs or fluids directly into the rich blood supply of the marrow. Since the marrow connects directly to the circulatory system, this method is fast and effective when IV access is difficult.

Common Uses

IO injections are usually reserved for critical emergencies such as:

- Cardiac arrest

- Severe trauma or accident injuries

- Overdose or poisoning

- Sepsis or septic shock

- Stroke or seizures

- Obstetric complications (e.g., childbirth emergencies)

They can also be used to administer anesthesia in dental procedures or deliver palliative care pain relief when veins are inaccessible.

Sites of Injection

Common IO access points include:

- The shinbone (tibia)

- The thigh bone (femur)

- The upper arm bone (humerus)

Risks and Side Effects

While injections are generally safe when performed by trained professionals, there are some risks. The CDC notes that common side effects include temporary pain, redness, swelling, or bruising at the injection site. Rare but serious risks may involve nerve damage, abscess formation, bleeding, or infection. Safe handling of needles and proper technique are critical to minimizing complications.

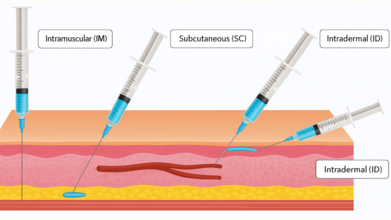

The Bizarre Foot Test That Could Point Towards A Heart Failure

Credits: Canva and Instagram

Thanks to Instagram and other such social media platforms, we know a lot about our health than before. In a video, a person presses on his lower leg, and instead of the skin bouncing back smoothly, it shows small pit-like impressions. The caption on the video reads: A Visible Sign Of Congestive Heart Failure.

A throbbing dorsalis pedis pulse, the artery running along the top of the foot, might appear harmless at first glance. However, doctors caution that such a finding can be an important clinical sign, often linked to conditions such as peripheral vascular changes or fluid overload. In particular, it may reflect elevated central venous pressure (CVP), a common feature of congestive heart failure (CHF).

Medical experts recommend that whenever this sign is seen, it should not be dismissed. Instead, patients should be assessed thoroughly, including checking bilateral pulses, looking for swelling in the legs or feet, and correlating these observations with blood pressure and a full cardiac examination.

Understanding Congestive Heart Failure

Congestive heart failure, also called simply heart failure, is a long-term condition where the heart cannot pump blood efficiently enough to meet the body’s needs. While the heart is still beating, it struggles to keep up with circulation demands. As a result, blood builds up in other parts of the body, most often in the lungs, legs, and feet.

Doctors often describe it with a relatable analogy: imagine a shipping department that is constantly behind schedule. Packages pile up because they cannot be dispatched on time. Similarly, in heart failure, fluid “packages” accumulate in the body, leading to symptoms and complications.

Different Types of Heart Failure

Heart failure is not a one-size-fits-all condition. It has different forms:

- Left-sided heart failure, where the left ventricle struggles to pump blood effectively.

- Right-sided heart failure, which often results from long-standing left-sided failure and leads to blood backing up in veins.

- High-output heart failure, a rare type where the heart pumps normally but the body demands more blood than it can provide.

- Right-sided heart failure is particularly linked to distended veins and visible pulsations, as seen in cases where fluid overload is present.

How Widespread Is the Problem?

Heart failure is alarmingly common. In the United States alone, more than six million people live with the condition, making it the leading cause of hospitalization among those older than 65. With aging populations and rising lifestyle-related diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, the burden of CHF is expected to grow further.

Common Symptoms Of Heart Failure

CHF can manifest in many ways, some subtle and others unmistakable. Typical symptoms include:

- Shortness of breath, especially during activity or at night

- Chest pain and palpitations

- Fatigue and weakness

- Swelling in the ankles, legs, and abdomen

- Weight gain and frequent nighttime urination

- A persistent, dry cough or bloating in the stomach

Some patients may experience only mild discomfort, while others face severe, life-limiting symptoms. Importantly, the condition tends to worsen over time if not managed.

Causes and Risk Factors

Several factors contribute to the development of heart failure, including:

- Coronary artery disease and heart attacks

- Long-standing high blood pressure

- Cardiomyopathy, often due to genetics or viral infections

- Diabetes and kidney disease

- Obesity, tobacco use, alcohol, or recreational drug use

- Certain medications, such as chemotherapy drugs

Risk increases with age, sedentary lifestyle, poor diet, and family history of heart disease. Left-sided heart failure is the most common trigger for right-sided failure, but lung diseases and other organ issues can also play a role.

Potential Complications

Unchecked heart failure can lead to serious complications such as irregular heart rhythms, sudden cardiac arrest, valve damage, fluid buildup in the lungs, kidney or liver failure, and malnutrition. These risks make early recognition of clinical signs, such as visible dorsalis pedis pulsation, critically important.

Diagnosing Heart Failure

Doctors use a combination of medical history, physical examinations, and diagnostic tests to confirm CHF. They typically ask about family history, lifestyle habits, medication use, and other medical conditions. Key tests include echocardiograms, ECGs, chest X-rays, MRIs, CT scans, stress tests, and blood work. In some cases, genetic testing may also be used.

Stages of Heart Failure

Heart failure is classified into four stages (A to D):

Stage A: High risk but no symptoms, often due to conditions like hypertension or diabetes.

Stage B: Structural heart problems but no outward symptoms.

Stage C: Clear symptoms alongside a confirmed diagnosis.

Stage D: Advanced heart failure with severe, treatment-resistant symptoms.

Why Medication Abortion Remains The Most Common And Safe Choice Even In 2025?

Credits: Health and me

In 2023, medication abortion emerged as the most common form of abortion in the United States, reflecting both the convenience and accessibility it offers. With evolving policies, telemedicine provision, and the continued demand for privacy and safety, understanding when and how medical abortion is recommended has become more critical than ever. Abortion in the United States has long been a controversial topic, but the increasing patchwork of state laws has made medical abortion all the more difficult to monitor.

Unlike surgical abortions that take place in clinics, medical abortions tend to occur in private locations with pills prescribed or even ordered over the internet something that makes it difficult to collect data. Throw in the recent round of restrictions and court battles, and researchers, policymakers, and clinicians are left with a distressing void: we just don't know how many medical abortions are being performed, where they are being performed, or what this looks like for women's health.

Although surgical abortion continues as a necessary procedure for specific circumstances, the growth of medication abortion has revolutionized reproductive health care by providing a safe and non-invasive alternative for termination during early pregnancy. This change also highlights the need for proper information, safe access, and quality follow-up care to provide positive health outcomes.

Latest figures from the Guttmacher Institute bring to fore that in the majority of U.S. states with less stringent abortion laws, medication abortion had represented 63% of total procedures offered during 2023. In Wyoming, as an example, 95% abortions were medication-related, with 84% taking the same route in Montana.

Even telemedicine is coming into play: an estimated 10% of medication abortions were provided solely online in states where telemedicine bans did not exist, with some states up to 60%. These trends highlight the importance of preserving and continuing access to abortion pills as an essential part of reproductive health care.

What is A Medical Abortion?

Medical abortion is a non-surgical and non-invasive procedure to end an early pregnancy, usually between 4 and 9 weeks. It uses a two-drug combination: mifepristone, to block progesterone required for continuing the pregnancy, and then misoprostol, which causes uterine contractions to pass the pregnancy. Dr. Rupali Mishra, sonologist and physician at Dr Rupali's Abortion Centre, describes, "Medical abortion is advised if the pregnancy is ensured to be intrauterine and the patient is medically fit".

This involves factors such as lack of severe anemia, bleeding disorders, chronic asthma, or allergies to drugs. She reiterates that availability of follow-up care, such as ultrasound scans to exclude retained products of conception (RPOC), is fundamental to the safe outcome.

When Is Medical Abortion Recommended By The Physician?

Medical abortion is most effective in the early weeks of pregnancy. For pregnancies nine weeks or less, the procedure may frequently be carried out outside of hospital facilities by trained health-care practitioners like gynecologists, nurse-midwives, or certified midwives. However, beyond nine weeks, medical abortion is carried out in hospitals with medical care because risks become greater and complications may arise. "Medical abortion is a convenient and non-invasive procedure, hence suitable for patients who value such factors," remarks Dr. Mishra.

The eligibility criteria too are medically oriented. The patient should not have ectopic pregnancy, severe chronic illnesses of heart, kidney, or liver function, or known contraindications to the medication. Written informed consent is legally mandatory in registered MTP centers to confirm understanding and safety of the patient.

Procedure and Follow-Up Care

After administration, patients can suffer from abdominal cramps, pain, and bleeding for 15–20 days. In most instances, there are no complications, but excessive bleeding, severe pain, or incomplete abortion can lead to a suction evacuation procedure. A follow-up ultrasound after about three weeks confirms the uterus is clear, marking the success of the procedure. Dr. Mishra states, "Even with high success rates, routine follow-up is critical to manage potential complications such as infection, prolonged bleeding, or retained tissue."

Safety Precautions and Possible Side Effects

Medical abortion is normally safe, but improper use or self-administration under unsupervised conditions can prove fatal. Heavy bleeding, incomplete abortion, infection, or, in exceptional cases, shock caused by undiagnosed ectopic pregnancy are serious side effects. Dr. Mishra cautions, "Selling abortion pills over the counter without a prescription is illegal and very risky. Medical supervision is a non-negotiable factor to avoid severe complications."

Medical Abortion vs. Surgical Abortion

Knowing the distinction between surgical and medical abortion enables proper patient decision-making. Surgical abortion is instant and appropriate for later gestation or incomplete medical abortion, whereas medication abortion is non-surgical and appropriate for early pregnancy. Both need follow-up for completion assurance and checking for complications.

What Role Telemedicine Play In Successful and Safe Abortion?

Telemedicine has revolutionized access to medication abortion, especially in states with less-restrictive laws. Virtual consultations with trained providers enable patients to get prescriptions and instructions without face-to-face visits, providing greater privacy and ease. However, according to Isabel DoCampo of the Guttmacher Institute, legal safeguards and access need to keep evolving in order to provide safe provision across states.

Medical abortion is safe, effective and becoming increasingly prevalent for the ending of early pregnancy if under qualified medical care.

Eligibility, procedure, and follow-up must be explained to patients so that safety and health can be assured. As reproductive health policy continues to change, maintaining access to safe abortion care—including medication and telemedicine—remains paramount. Open dialogue with objective medical professionals, coupled with adequate support and counseling, continues to be imperative for enabling individuals to make responsible decisions regarding their reproductive well-being.

Disclaimer: This article is provided for informational purposes and is not medical or legal advice. Readers are urged to seek advice from qualified healthcare providers for medical advice and to consult state or federal authoritative resources for updates on the laws of abortion in the United States.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited