How Colonialism Continues To Bear An Impact On The South Asian Health Crisis

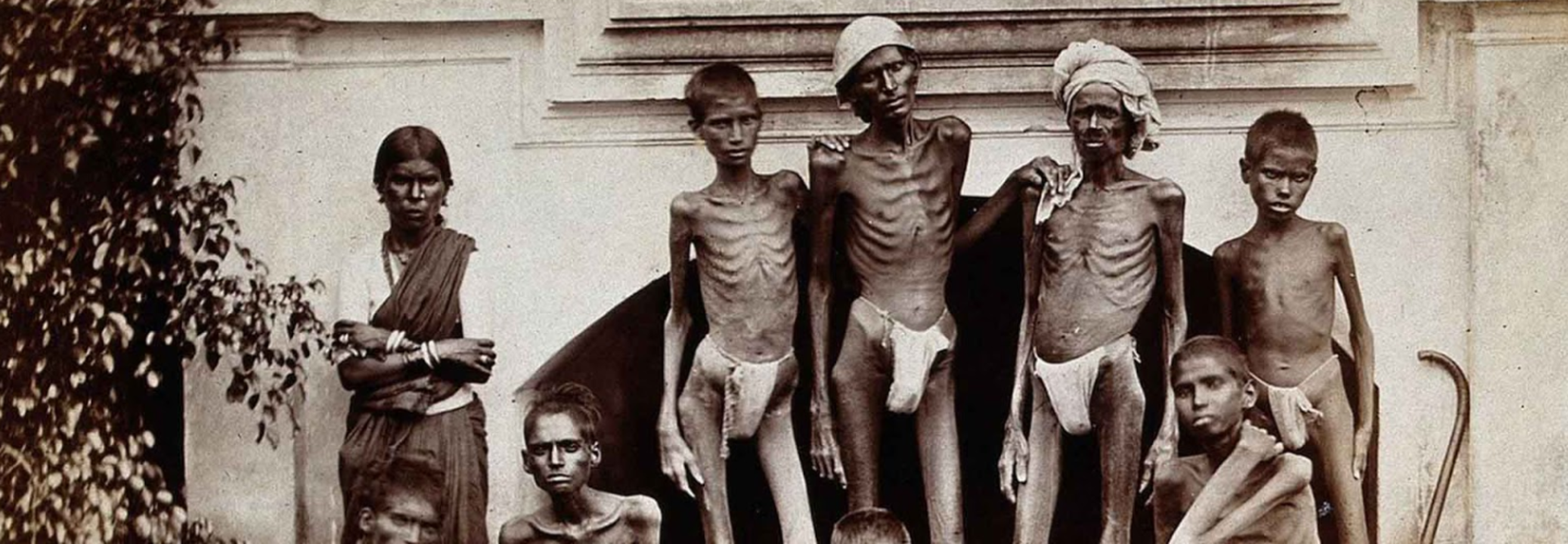

A family during the Madras Famine - 1876 (Photo by: Willoughby Wallace Hooper)

SummaryColonialism disrupted South Asia’s health systems, causing long-term impacts like diabetes and heart disease due to famine exposure, inequitable care, and biological changes—issues that still shape health outcomes today.

End of Article