- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

India Confirms 1st Bird Flu Human Death In 4 Years—Know Everything About It

Credit: Canva

India has reported its second human fatality due to highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) or bird flu, marking the first such death in four years. While bird flu infections in humans are rare, they are highly lethal, with a fatality rate of one in two cases. The most recent victim was a two-year-old girl from Palnadu, Andhra Pradesh, who passed away in mid-March after being hospitalized for over 10 days at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Mangalgiri.

The pathogen responsible for the infection and subsequent deaths was confirmed only on 31 March, following a survey by the Indian Council of Medical Research-National Institute of Virology (ICMR-NIV). According to details shared by the state government, the child, who had a habit of consuming raw chicken, was admitted to the hospital on 4 March with symptoms including fever, breathlessness, nasal discharge, seizures, diarrhea, and reduced feeding. Two days before falling ill, she had reportedly consumed raw chicken. She succumbed to the infection 12 days later.

In a statement issued on Wednesday, the state government noted that no abnormal cases of respiratory infections had been identified in the ongoing survey. However, surveillance will continue for the next two weeks, with testing arranged for any suspected cases. Union health ministry officials stated that, based on data from the Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme (IDSP), no unusual surge in influenza-like illness (ILI) or severe acute respiratory illness (SARI) cases has been observed in the district in recent weeks.

A national joint outbreak response (NJOR) team has been deployed to conduct an epidemiological investigation and provide assistance to the state.

3 States Impacted By Bird Flu

This year, outbreaks of HPAI—also known as Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 or bird flu—have been reported in Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh. The trend follows a similar pattern observed in 2024, when states such as Jharkhand and Kerala, along with the aforementioned three states, recorded widespread H5N1 infections in poultry, prompting authorities to cull thousands of birds.The Union government emphasized that "human-to-human transmission of the H5N1 virus is uncommon, and the risk of any other epidemiologically linked case being reported is assessed to be low."

India's first recorded human infection of the H5N1 influenza virus occurred in 2021 when an 18-year-old boy in Haryana succumbed to the infection within days of contracting it.

In May last year, Australia reported its first human infection with H5N1, stating that the patient had acquired the virus in India. Towards the end of 2024, the deaths of four big cats—three tigers and a leopard—were attributed to H5N1 infection.

Jana Duggar Is Pregnant: Why the First Few Weeks of Pregnancy Matter More Than You Think

Credits: Canva, janamduggar/Instagram

Counting On star Jana Duggar, 35, and her husband, Stephen Wissmann, are expecting their first baby. The couple, who tied the knot last year, shared their happy news on Instagram with a glowing caption. Fans went wild, but beyond the sweet announcement, there is something worth talking about: the earliest weeks of pregnancy, when so much of the story of new life quietly unfolds.

Pregnancy is often spoken about in trimesters, but the very beginning, the hush-hush early weeks, is where the groundwork is laid for everything to come. And whether you are a reality TV star or not, those first days carry immense importance.

Many women do not even realise they are pregnant in the earliest days, but the body is already in full construction mode. Hormones like hCG (the one that makes pregnancy tests turn positive) and progesterone start working overtime to prepare the uterine lining, support the embryo, and guard against early complications.

Why “Early Care” Is Everything

Doctors always stress that if you are planning a pregnancy or even just considering it, those first few weeks are the ones you need to prepare for the most. Folate, for instance, is a superhero nutrient in these early days. Adequate folic acid before and during early pregnancy can prevent neural tube defects, serious conditions that form in the embryo’s first month.

Skipping prenatal vitamins during this window is like forgetting to pack your parachute before a skydive. Most of the development of the brain and spinal cord happens before you even hit 12 weeks.

The Unseen Risks of Everyday Life

The early days are also when lifestyle habits make the biggest difference. Alcohol, smoking, and even certain over-the-counter medications can have a bigger impact during this time than later on. That is why many doctors advise women of childbearing age to adopt healthy routines before conception itself.

It is not just the headline habits either. Too much caffeine, poorly cooked meats, or even that unwashed salad can carry risks in early pregnancy when the immune system is slightly suppressed. It might sound fussy, but those small adjustments help lay a safe foundation for the months ahead.

Why Rest and Stress Matter A Lot

Everyone loves telling expectant mothers to “rest”, but in those early days, rest is not just about catching up on Netflix. It is about helping the body handle the metabolic overload of creating a new human. Fatigue is often one of the first pregnancy symptoms, and it is not just in your head; the body is literally doubling its workload.

Stress, too, plays a silent role. High cortisol levels can affect implantation and early growth. While it is impossible to live stress-free, the early days are when building calming routines, whether through gentle exercise, journaling, or mindfulness, can pay off in the long run.

The Emotional Rollercoaster Nobody Warns You About

The funny thing about early pregnancy is how invisible it feels. Outwardly, nothing looks different, but inside, everything is changing. That mismatch can be confusing. Some days it is all excitement, baby names, nursery ideas, and Instagram reveals. Other days it is nerves; what if something goes wrong?

That duality is completely normal. Roughly 1 in 4 pregnancies end in miscarriage, most often during those early weeks, and while the statistic can be scary, it is also why early prenatal care and open conversations are so important. A good support system can help balance joy with realism.

Why Jana’s News Hits Different

At 35, 19 Kids and Counting star falls into what doctors call “advanced maternal age”, which simply means pregnancies need a little more monitoring. But it is also proof that every journey is unique. The fact that she and Stephen are openly celebrating the news shows how much hope and excitement early pregnancy carries, even in its uncertainty.

For her, January 2026 will bring a baby. For the rest of us, it is a reminder that the earliest weeks of pregnancy, while quiet and often unseen, are some of the most powerful days in the making of a new life.

While the first weeks of pregnancy may not come with a visible bump or cute baby kicks, they are the foundation of the entire nine-month journey.

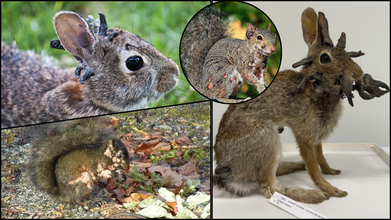

From 'Frankenstein Rabbits' To 'Zombie Squirrels': What These Unsettling Traits Reveal About Parasitic Illnesses

Credits: AP/Evelyn's Wildlife Refuge/X

Every summer, social media fills with unsettling images of backyard wildlife that look more like extras from a low-budget horror movie than neighborhood critters. This year, it’s squirrels with grotesque sores and rabbits sprouting what appear to be black, tentacle-like horns from their heads. While the sight is shocking, scientists say these conditions are less terrifying than they appear—and in many ways, they’re teaching us important lessons about viruses, immunity, and even human health.

In northern Colorado, residents recently spotted wild rabbits with twisted, horn-like growths protruding from their faces. Reports came in from Fort Collins, where some of these animals looked like they had sprouted black tentacles instead of fur.

What Are Frankenstein Rabbits?

Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) quickly confirmed the culprit- Shope papillomavirus, a virus first identified in the 1930s. The infection causes keratin-based growths made of the same material as human nails and hair—that can grow into elongated, horn-like shapes.

For most rabbits, the infection is temporary. “They’re able to clear it from their system on their own,” says Kara Van Hoose, CPW spokesperson. Once the immune system suppresses the virus, the horns dry out and eventually fall off. But in some cases, the growths can interfere with eating, foraging, or even vision. Rarely, they can develop into squamous cell cancers.

Importantly, Shope papillomavirus only infects rabbits and hares—not humans or pets. The growths themselves aren’t contagious. Instead, the virus spreads via bites from mosquitoes, fleas, and ticks, which is why sightings spike in summer and then fade with the first frosts.

A Virus with A Surprising Legacy

The rabbit virus may look like a strange wildlife quirk, but its scientific significance is immense. Richard Shope, the virologist who identified it in 1933, later contributed to research on influenza A and traced links to the deadly 1918 flu pandemic.

Even more importantly, his studies of rabbit papillomavirus helped scientists understand human papillomavirus (HPV), a pathogen now known to cause several cancers. This research eventually led to the development of the HPV vaccine, one of the most effective tools in modern cancer prevention.

In other words, the bizarre-looking horned rabbits of Colorado are part of a story that connects animal health, human medicine, and the fight against one of the world’s leading cancer-causing viruses.

What Are Zombie Squirrels?

If the horned rabbits weren’t alarming enough, homeowners across the U.S. and Canada have reported squirrels with grotesque, oozing sores. Dubbed “zombie squirrels” on Reddit and local news outlets, these animals often appear bald, scabby, and covered in tumors.

At first, some feared this was squirrelpox, a rare and often deadly virus primarily found in red squirrels in the U.K. But experts now say that in North America, most cases are actually squirrel fibromatosis, caused by a virus called leporipoxvirus.

Like the rabbit papillomavirus, fibromatosis creates wart-like growths that may burst and ooze fluid. The disease looks disturbing, but it usually clears up on its own within four to eight weeks. Gray squirrels, which are common across the U.S., generally recover fully.

How the Virus Spreads Among Animals?

Unlike the horned rabbit virus, which is spread by biting insects, squirrel fibromatosis spreads through direct contact with infected saliva or lesions. That means the backyard bird feeder—a favorite stop for squirrels—can act as a transmission hub. Infected squirrels may leave saliva on seeds, which is then picked up by others.

“Shevenell Webb, a wildlife biologist in Maine, explains it like this: ‘It’s like when you get a large concentration of people. If someone is sick and it spreads easily, others are going to catch it.’”

Although it’s upsetting to see squirrels in such poor condition, the disease does not spread to humans, dogs, or cats. Experts strongly advise against touching or attempting to “rescue” infected squirrels.

Should We Worry About Human Risk?

Here’s the key point: Neither rabbit papillomavirus nor squirrel fibromatosis poses a risk to people. These viruses are species-specific, meaning they evolved to target only their animal hosts.

That said, wildlife experts caution against close contact. Wild animals can carry other pathogens, and distressed animals can bite or scratch. The safest approach, they say, is observation from a distance.

At first glance, these conditions look like nothing more than cruel tricks of nature. But the history of virology shows that studying animal viruses has repeatedly advanced human medicine. The rabbit papillomavirus directly contributed to the eventual creation of the HPV vaccine. Even squirrel fibromatosis, though less studied, provides clues about viral behavior, transmission dynamics, and immune response.

There’s also a conservation angle. Tracking these conditions helps wildlife officials monitor population health and understand how environmental changes, including warmer summers and denser urban habitats, may amplify disease spread.

It’s worth noting that both the horned rabbits and zombie squirrels came into the public spotlight through viral photos online. Platforms like Reddit and X (formerly Twitter) have become informal early-warning systems for unusual animal illnesses. While this sometimes fuels fear, it also provides wildlife agencies with useful crowd-sourced data.

As Van Hoose points out, it’s difficult for agencies to know whether multiple sightings represent several infected animals or just the same one seen repeatedly. Public reports when paired with expert analysis help build a clearer picture.

What to Do If You Spot A ‘Frankenstein Rabbits’ or ‘Zombie Squirrels’?

If you see a rabbit with horns or a squirrel with sores, the advice is straightforward:

- Do not touch or feed the animal.

- Do not attempt to trap or euthanize it.

- Report sightings to local wildlife authorities if requested in your area.

These animals, though unsightly, are usually not suffering long-term. Many recover naturally once their immune system clears the virus.

From rabbits with keratin “horns” to squirrels with wart-like sores, these strange cases highlight how deeply intertwined wildlife health is with human understanding of disease. They remind us that viruses are not just human problems—they shape ecosystems, influence evolution, and sometimes, unexpectedly, lead to breakthroughs that save lives.

First-Of-Its Kind Study On Head And Neck Cancer, Researchers Find Whether Weed Could Negatively Affect Treatment

The debate about how weed or cannabis supplements are health friendly are not has been going on for a while. While there are certain benefits of it for psychological health, it still has physical consequences. When it comes to surgeries and healing, there are many things that need to be considered.

Doctors know that many cancer patients use cannabis to help with symptoms like nausea, pain, and anxiety. In fact, some studies show that more than half of cancer patients, and up to 80% of those who also smoke tobacco, use it. But there's a big missing piece of information: How does cannabis use affect the body’s ability to heal from surgery?

As we know, smoking negatively affects how well your wounds heal, however, when we swap the components to cannabis, how different is the effect?

How Does Cannabis Affect Recovery From Cancer Surgery?

To answer this, Dr. Lurdes Queimado at the University of Oklahoma is leading a first-of-its-kind study focused on patients with head and neck cancers. These cancers are becoming more common, fueled by smoking, heavy drinking, and HPV infections.

The primary treatment for them is often surgery, which can be life-changing, as it often alters a person's appearance and affects their ability to breathe and swallow. Because of these intense surgeries, patients often need reconstructive surgery afterward. The goal of this research is to give doctors clear, reliable information so they can properly advise their patients on how cannabis might affect their recovery.

How the Study Works

This study will follow 220 adult patients over a six-month recovery period after their surgery. It's unique because it's a "prospective" study, meaning the researchers are tracking patients as they heal, rather than just looking at old records. To make sure the data is accurate, they’ll also use blood tests to confirm if patients are using cannabis.

- Cannabis users

- Tobacco users

- Both cannabis and tobacco users

- Those who use neither

Over the six months, the research team will closely watch each patient for infections, bleeding, and other medical complications. They’ll also carefully assess how well their scars are healing. The study will also explore if the way someone uses cannabis—whether by smoking, vaping, or using edibles—makes a difference in their recovery.

What Doctors Expect to Find

Based on some early research, Dr. Queimado and her team have a hypothesis: smoking cannabis could have a negative impact on wound healing. Their initial findings suggest that even in healthy people, cannabis can increase inflammation and weaken the immune system. Both of these effects could potentially slow down healing and lead to more problems after surgery.

This research could have a huge impact. Not only could it help patients with head and neck cancer, but it could also provide valuable information about how cannabis affects other chronic diseases where inflammation and a strong immune system are important. Ultimately, the findings could shed light on how cannabis interacts with other cancer treatments like chemotherapy and radiation, giving doctors a much clearer picture of its overall effects on a patient's health.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited