- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Is Climate Change Draining The World's Blood Banks?

In the aftermath of a global pandemic, with the memory of oxygen shortages still fresh and the threat of new infectious diseases looming large, the world's healthcare systems are stretched thinner than ever. We're battling overlapping health crises- resurging malaria and dengue cases, the global spread of West Nile virus, new strains of flu, antibiotic-resistant infections, and a growing mental health epidemic. Public health is in constant firefighting mode but there is one quiet casualty of this mad world that seldom hits the headlines—our blood supply.

Blood—so simple, so essential—lies at the very center of modern medicine. Whether it's stabilizing a trauma victim, sustaining a cancer patient through chemotherapy, or enabling women to survive complicated delivery, the presence of safe, screened, and timely blood transfusions is not negotiable. And yet, today, that lifeline is being quietly and methodically disrupted.

As global warming picks up, it is progressively eating away at all levels of the blood supply chain—donor health to storage conditions to transportation logistics. Intense heatwaves deter donors, electricity failures weaken storage refrigeration, and flooding or forest fires slow blood unit delivery. Insects that transmit blood-borne illnesses such as dengue and West Nile virus are spreading to new areas as a result of altered weather patterns, complicating and accelerating blood screening. In short, what was once a relatively predictable system is now under attack from unpredictable climatic events.

This isn't a remote threat—it's occurring today. A recent study in The Lancet Planetary Health cautions that climate change may compromise the safety, adequacy, and availability of blood supplies around the world. Investigators have demanded proactive measures: additional mobile and versatile blood collection units, enhanced disease monitoring, and global cooperation to maintain resilience against environmental shocks.

Behind all the science and statistics stands a human narrative: a father in need of blood following a car accident, a child with sickle cell disease, a pregnant woman. Their lives are not only dependent upon donors, but upon a system powerful enough to withstand the floods—literally.

As the planet's climate crisis gains speed, its effect is no longer limited to melting glaciers or sea level rise—it now runs in our veins, literally. The integrity of the global blood supply is becoming a vital, under-covered casualty of global warming. With millions depending on secure blood transfusions for surgeries, trauma, cancer treatment, and the control of chronic disease, interruptions to the blood supply chain can be disastrous for public health systems globally.

From shifting donor supply to jeopardizing storage and transportation logistics, climate change is quietly mounting pressure on every step along the blood supply chain and with the planet warming up, so does the imperative for health systems to do the same.

Blood is the foundation of emergency care and chronic patient management. Over 25 million units of blood are transfused every year in Europe alone, treating victims of accidents, premature babies, and patients with diseases such as sickle cell disease and cancer but providing a steady, clean supply of blood involves a precarious balance of infrastructure, logistics, and volunteer donors.

This equilibrium is increasingly disrupted by climate-related disturbances—severe heat, floods, storms, and disease outbreaks—that affect everything from donor engagement to safe blood transportation and storage.

How Climate Events Disrupt the Blood Supply?

Severe weather events like hurricanes, floods, wildfires, and heatwaves are becoming more frequent and intense, directly impairing the capacity to obtain, test, store, and distribute blood products. Such events can physically destroy facilities, restrict staff and donor mobility, or lead to spontaneous spikes in demand because of injury.

Natural disasters not only disrupt transportation and storage but also reduce the pool of available donors, said Red Cross Lifeblood and University of the Sunshine Coast (UniSC) Australian Australia's Dr. Elvina Viennet. "These events upset the storage, safety, and transport of blood, which has a limited lifespan," she said.

The effect is not hypothetical; when hurricane Harvey struck in the US, for example, hundreds of blood drives were canceled, creating regional shortages. In these emergencies, there is frequently a simultaneous and urgent rise in demand for blood and fall in supply—a health system's worst nightmare.

Increased rainfall and global warming have pushed the geographical limits of vector-borne illnesses such as dengue, malaria, and West Nile virus—some of which are transmissible through blood. Ideal breeding conditions for mosquitoes are promoted by warmer climates, which makes transfusion-transmissible infections (TTIs) a matter of concern.

"Climate change could affect some blood-borne infectious diseases that can exclude individuals from donating," Viennet said. This complicates and costs more to screen blood, overloading already stressed health systems.

Europe has already seen an increase in dengue cases previously unusual in the region illustrating the speed at which new threats are arising because of changes in the environment.

Donor Health and Availability in a Changing Climate

Aside from infectious diseases, climate change can also have a direct impact on donor health. Heat, air pollution, dehydration, and cardiovascular stress can decrease the number of eligible donors. Even minor physiological changes—such as changes in haemoglobin levels due to heat—can disqualify donors.

There is also a mental health angle to consider where climate anxiety, post-disaster trauma, and stress from displacement can reduce donor participation. The study pointed to increased anxiety and depression among both donors and healthcare workers in the aftermath of extreme weather events.

As climate change worsens chronic conditions—specifically cardiovascular and respiratory disease—it also raises demand for blood transfusions. Complications of pregnancy, sickle cell crises, and surgeries can become more common, adding demand-side pressure to blood banks.

This combined risk of dwindling supply and escalating demand is not abstract; it's already materializing. Left unchecked, health systems could soon experience catastrophic care gaps.

Ways to Protect Blood Supplies in a Warming World

To combat this impending crisis, scientists and policymakers recommend a multi-faceted strategy:

- Mobile and flexible blood donation facilities that can function during and after severe weather conditions.

- Global cooperation to exchange blood supplies across borders during scarcity.

- Research investment to learn how climate factors affect donor health and blood stability.

- Implementation of cell salvage methods (autotransfusion) in operating rooms to minimize dependence on external blood supply.

Increased diversity donor recruitment, particularly from migrant communities, to more closely match rare blood groups and meet altered demographics.

As UniSC's Dr. Helen Faddy pointed out, "With sea levels rising and migration rates growing, it's critical to have a greater number of blood donors from diverse ethnicities."

The blood supply is not only a technical problem—it's a human one. While climate change continues to test the world's health systems, protecting our blood supply has to be an absolute priority. The danger is multiple- biological, logistical, psychological, and infrastructural like the climate crisis itself, it requires global action, scientific innovation, and urgent, sustained effort.

How Age And Genetics Can Determine Antibodies Production In Your Body

Credit: Canva

Ever wondered how your body generates antibodies in the face of a virus attack? A new study by French researchers showed that our age, biological sex, and human genetic factors can determine our immunity levels.

The human body, when exposed to a virus, defends itself by producing molecules called antibodies. Their main function is to identify pathogens and kill them.

Scientists from the Institut Pasteur, the CNRS, and the Collège de France noted that these factors not only boost the quantity of antibodies produced in the body but also determine the specific viral regions to target.

The February 2026 study, published in the journal Nature Immunology, can pave the way for the development of personalized treatments, especially for individuals who are most vulnerable to infection.

"This study provides a detailed, integrated view of how age, sex, and human genetics shape the antibody response," said Lluis Quintana-Murci, Head of the Human Evolutionary Genetics laboratory at the Institut Pasteur.

"It shows that these factors even determine which specific regions of a given virus are targeted by antibodies, with important implications for vaccine and therapeutic design," Quintana-Murci added.

How Age And Sex Influence Immunity

The findings revealed that individuals produce antibodies that target different parts of the virus when attacked by the same virus. Age was identified as the dominant factor influencing antibody production. The team noted that more than half of the antibody repertoire varies depending on age.

Further, some antibodies were found to increase with age, while others decreased. This was seen particularly in the case of influenza H1N1 and H3N2 viruses.

In young adults, the antibodies mainly targeted a part of the viral surface protein known as hemagglutinin (HA), which evolves rapidly. In older individuals, it focused on a more stable region of the same protein known as the stalk domain.

Women were also found to produce more antibodies against HA. On the other hand, men tended to target other viral proteins (NP and M1), despite comparable vaccination rates between the two sexes.

How Human Genetics Shape Antibody Production

The team identified mutations in genomic regions known to encode the immunoglobulin repertoire. These variants determine which genes are used to produce antibodies.

Using an African cohort, the study revealed population disparities in terms of the molecular targets of their antibody repertoires.

In the case of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), antibodies were found to recognize different viral proteins depending on the geographical and epidemiological context.

This difference can be explained by the level of exposure -- Africans are more exposed to a particular strain of EBV in which the protein EBNA-4 is the primary antibody target.

How Was The Study Conducted?

The research is based on data from the Milieu Intérieur cohort, launched 15 years ago to study variations in the immune response in 1,000 healthy individuals.

Using an innovative sequencing technology, the scientists analyzed blood plasma samples to measure antibody responses against more than 90,000 fragments of viral proteins, covering a large number of viruses responsible for infections such as influenza, respiratory infections, gastroenteritis, and herpesvirus infections.

Epstein Files: Post-mortem Notes And New Documents Shed Light On Late Sex Offender's Death

Epstein Files: After the Department of Justice (DOJ) released more files on the late sex offender and financer Jeffrey Epstein, previously unseen photographs, including medical details and a detailed timeline of his final weeks in custody have resurfaced. All of this new information has added fresh scrutiny to the case.

A 23-page long document, labelled unclassified titled Jefferey Epstein Death Investigation was prepared by the New York field officer of the FBI. The material has been examined by BBC Verify and was reported to contain close-up images of Epstein's body, notes from his post-mortem examination and psychological observations that were recorded shortly before his death in August 2019.

As per BBC, the photographs included detailed views of injuries to Epstein's neck and show medics attempting to resuscitation after he was found unresponsive in his jail cell. As per the timestamps visible in the files, the images were taken at 06:40 local time on 10 August 2019, almost 16 minutes after a prison staff discovered him.

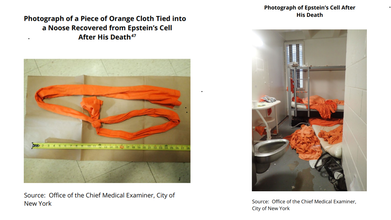

As per the DOJ's Office of the Inspector General's review report released in June 2023, on August 10 at 6.30am, two SHU staff on duty CO Tova Noel and Material Handler Michael Thomas delivered breakfast to inmates, when Noel was delivering breakfast from the food slot of the door to Epstein's SHU tier, there was no response. Thomas unlocked the door and saw Epstein hanged. The review report mentions that he immediately "yelled for Noel to get help and call for a medical emergency". According to Noel, within seconds of Thomas calling out for the clutter she hit the body alarm, which is a button on an MCC staff member's radio that is used to signal distress or an emergency. Noel also recalled Thomas saying, "Breathe, Epstein, breathe." As per Noel, when she saw Epstein, he looked "blue and did not have a shirt or anything around his neck".

Read: Epstein Files Photos Show A Bottle Of Phenazopyridine, Why We Think This UTI Medication Was There

As per Thomas, when he entered Epstein's cell, he had an orange string, from a sheet or a shirt, around his neck that was tied t the top portion of the bunkbed. The review report notes: "Epstein was suspended from the top bunk in a near-seated position, with his buttocks approximately 1 inch to 1 inch and a half off the floor." As per Thomas, he immediately ripped the orange string from the bunkbed and Epstein's buttocks dropped to the ground, and lowered him to begin chest compressions until staff arrived.

As per the BBC reports, the location is not explicitly stated in the documents, but records indicate Epstein had already been transported to hospital at 06:39, where he was later pronounced dead, suggesting the images were likely taken there.

Some of the photographs show a tag attached to his hand with his name and date of death. In several images, however, his first name appears misspelled as “Jeffery”.

Epstein Files: Post-Mortem Of Jeffrey Epstein And Custody Timeline

The investigation file incorporates sections of an 89-page post-mortem report compiled jointly by the Department of Justice and New York’s Office of Chief Medical Examiner. Among the medical findings were scans documenting fractures in the thyroid cartilage of Epstein’s neck.

BBC Verify said it conducted reverse image searches and “could not find earlier versions” of the photos online before their recent release, indicating they had not previously circulated publicly.

The report also reconstructs Epstein’s detention inside the Metropolitan Correctional Center from his arrest on 6 July 2019 on federal sex-trafficking charges to his death five weeks later.

According to the timeline, Epstein was placed on suicide watch after a 23 July incident in which he was found injured in his cell. At the time, he claimed his cellmate — Nicholas Tartaglione — had attacked him.

Epstein Files: Jeffrey Epstein's Psychological Assessment Before His Death

The following day, during a psychological assessment, Epstein denied wanting to harm himself. BBC reported the document states he said he had “no interest in killing myself” and that it “would be crazy” to do so. Two days later, notes record him saying he was “too vested in my case” and wanted to return to his life.

Despite that, prison officials had recommended he not be housed alone and that guards perform checks every 30 minutes, including unannounced rounds.

The newly released records outline several security lapses the night before Epstein died.

His cellmate had been transferred out the previous day, leaving him alone. Prison logs show guards failed to conduct scheduled checks at 03:00 and 05:00, and the unit’s camera system was not functioning. Staff later discovered his body during a morning inspection.

The files also include two versions of the same FBI report: a full 23-page unredacted copy and a shorter 17-page redacted version that omits the psychological report and detention timeline. The reason for the dual publication has not been explained.

The Department of Justice has been contacted for comment, while the FBI declined to respond, reported BBC.

The release of the material does not change the official ruling of suicide, but its level of detail, particularly the photographs, mental-health notes and security failures — is likely to reignite debate over the circumstances surrounding Epstein’s death.

Parents Across the U.S. Report Difficulty Finding Mental Health Care for Their Child

Credits: Canva

As per the American Psychological Association (APA), only 58.5 per cent of US teens always or usually receive the social and emotional support they need, as per the report by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Another National Institutes of Health (NIH, US) report notes that the most mental health disorders among children ages 3 to 17 in 2016 to 2019 were attention deficit disorder (9.8%, approximately 6 million), anxiety (9.4%, approximately 5.8 million), behavior problems (8.9%, approximately 5.5 million), and depression (4.4%, approximately 2.7 million). For adolescents, depression is concerning because 15.1% of adolescents ages 12-17 years had a major depressive episode in 2018-201.

However, not all are able to receive the help, in fact, parents too find themselves struggling when it comes to helping their children.

Despite growing concern about a mental health crisis among young people in the United States, a large national study suggests the care system continues to fall short for many families.

Researchers from the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute in Boston found that nearly one quarter of children who require mental health treatment are not receiving it.

The findings come from survey data collected from more than 173,000 households between June 2023 and September 2024.

Many Families Recognize the Need but Cannot Get Help

The analysis showed that about one in five households, or 20 per cent, had at least one child who needed mental health support. Yet among those families, nearly 25 per cent said those needs were not met.

Even families that eventually obtained care often faced significant hurdles. Nearly 17 per cent described the process as difficult and exhausting.

The research letter was published February 16 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Household Structure Shapes Access

The study found that family circumstances strongly influenced how easy it was to navigate the health care system.

Families with multiple children reported higher unmet needs at 28 per cent, compared with 21 per cent in households with only one child. Single parent households also reported more difficulty securing appointments.

Education setting played a role as well. Homeschooled children had higher unmet needs at 31 per cent compared with 25 per cent among children attending public school. Researchers suggest this may reflect the absence of school counselors and other school based support systems.

Insurance and finances created additional barriers. About 40 per cent of families covered by Medicaid or without insurance said they could not get care specifically because it was too hard to access.

In a news release, lead author Alyssa Burnett said nearly one quarter of parents reported that at least one child did not receive needed mental health care, highlighting persistent access gaps.

Cost, Availability and Logistics Remain Major Obstacles

Researchers noted several common barriers. Families cited treatment costs, a shortage of clinicians and logistical issues such as scheduling and travel.

The study also found disparities among racial and ethnic groups. Families from minority backgrounds had higher rates of unmet needs compared with non Hispanic white households. However, Black households reported less difficulty accessing care at 13 per cent compared with 17 per cent among white households.

Bringing Care Closer to Families

Experts involved in the study say improving access may require shifting where care is delivered.

Senior author Hao Yu, an associate professor of population medicine at the institute, said states should expand the child mental health workforce and integrate mental health services into primary care settings to remove barriers and improve access to needed treatment.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited