- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Is There A Limit To How Far Female Fertility Can Be Extended?

Credits: Canva

Over the past century, social progress has greatly altered the age at which women opt to have children. Whereas most women in the past gave birth in their early twenties or teens, the trend has since dramatically changed. Women in nations such as the U.S., South Korea, and in Europe are now delaying motherhood to well into their 30s. Indeed, the average age of first-time mothers in most OECD countries now stands at about 30.

But biology has not kept pace with society. Women's fertility is still tied to the natural aging of a woman's reproductive apparatus – something that modern medicine is always trying to get around. With career aspirations, education, and individual choice rewriting the schedules of motherhood, an urgent question presents itself: how far can we push back female fertility?

How Does The Biological Clock Work?

At the very center of female fertility is a game of numbers – one that is decided even before a girl is born. Women are born with a limited number of eggs, usually one million. By the time they reach puberty, this count drops to about 300,000. Of these, only some 300 to 400 will ever develop and get released during ovulation.

By age 37, egg stores decrease to around 25,000, and by age 51 – the average age of menopause in the United States – only 1,000 are left. Yet, ovulation and fertility do not necessarily persist up to menopause. In the majority of women, natural fertility declines sharply 7 to 10 years before, typically by the early 40s.

Though this fall has been around for some time, its raw statistics still stun: natural conception chances fall from about 25% per cycle during a woman's 20s to less than 5% per cycle by her 40s.

What Does the Egg Supply Do at Each Age?

More important than the declining egg quantity is the sharp decline in egg quality with advancing age. Each egg contains chromosomes that make up the DNA map for a new life. When egg quality falls, so does the chance for a successful pregnancy.

By age 30, nearly 25–30% of a woman’s eggs may carry chromosomal abnormalities. By 35, this rises to 40%, and after 40, it spikes dramatically. Studies show that beyond age 40, up to 75% of eggs may have abnormalities. Such eggs are less likely to fertilize, implant, or lead to a healthy baby.

The dangers posed by low quality of eggs are miscarriage, unsuccessful fertility treatment, and chromosomal abnormalities such as Down syndrome.

How Far Can Science Go in Extending Fertility?

With the help of improvements in assisted reproductive technologies (ART), the limits of biological fertility are gradually being extended. Methods like egg freezing (oocyte cryopreservation), in vitro fertilization (IVF), and the employment of donor eggs have helped many women give birth well into their 40s – and, in some instances, even their 50s.

Egg freezing, specifically, has been a game-changer. It enables women to save their younger, healthier eggs to use later in life. It's not a surefire insurance policy, though. Success is dependent on age at the time of freezing, number of eggs saved, and overall health.

Nevertheless, though technology may provide additional time, it will not halt the natural aging of the ovaries or enhance the genetic quality of aging eggs. There is still a biological limit.

Decrease in Male Fertility Level

Men, too, experience a decline in fertility – but it tends to occur more gradually. Starting around age 40 to 45, men see a drop in sperm quality and volume, but they often retain the ability to father children into their 60s and beyond. Unlike women, men continuously produce new sperm, whereas women are working from a non-renewable stockpile of eggs.

This disparity implies that while more and more couples are opting to wait to have children, the responsibility of the "biological clock" remains mostly on women.

Although most of the discussion about female reproductive aging centers on wanting to have children, it is important to note that it also marks more general changes in a woman's health – specifically the onset of menopause and its attendant risks. Perhaps one of the most important but most underappreciated is the increasing significance of regular reproductive screenings, particularly as women get older.

Among these, cervical cancer screening stands out as a powerful tool to protect women’s health beyond their childbearing years.

Pap smears and HPV testing are able to pick up on abnormal cell changes before they develop into cancer. Because the immune system shifts with age and hormonal changes impact cervical health, regular screening is even more important. Women in their 30s and 40s – the same time frame when fertility is actively shifting – need to continue to be vigilant about their yearly OB-GYN checkups.

Actually, while women are thinking of or undergoing fertility treatments or assessing their reproductive future, this is the ideal opportunity to make sure their cervical health is under surveillance. New technologies in at-home HPV testing, liquid-based cytology, and co-testing provide more convenient and precise diagnoses ever before.

So is there a boundary beyond which female fertility can be prolonged? Biologically, yes. Despite incredible scientific strides, the natural aging of eggs and of the ovaries places limits that technology can only stretch so far.

Yet reproductive health is more than fertility. By broadening the story to encompass cervical screenings and preventive care, we give women the ability to take holistic control of their reproductive path – whether they opt to become mothers at 25, 35, or older because prolonging fertility isn't merely about having the capacity to conceive, it's about maintaining a lifetime of reproductive health.

Norovirus 2025: Is There A Vaccine For The Stomach Bug Spreading This Year?

Credits: Canva

Dozens of norovirus outbreaks have been recorded nationwide over the past few weeks, and as people deal with intense vomiting, diarrhea, and other uncomfortable or even risky symptoms, a common question keeps coming up: why is there still no vaccine for such a widespread infection.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says norovirus cases are increasing toward the end of 2025, with higher activity reported in both the US and the UK. Health officials note that a new, highly infectious strain known as GII.17 is partly driving this rise. Because many people have little or no immunity to it, outbreaks are being seen more often in schools and shared public spaces. While overall case numbers remain within typical seasonal ranges, recent weeks have shown a clear upward trend.

What Is Norovirus?

Norovirus is an extremely contagious virus that leads to gastroenteritis. It commonly causes symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, nausea, and stomach cramps, and may also bring fever and body aches. It is often referred to as the ‘stomach flu,’ though it has no connection to influenza.

The virus spreads quickly through contaminated food or water, shared surfaces, or direct contact with an infected person’s vomit or stool. Crowded settings like cruise ships are especially vulnerable. Most people recover within one to three days with rest and enough fluids, according to the CDC.

Norovirus Symptoms 2025

Norovirus usually comes on suddenly, causing vomiting, watery diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain. Fever, headaches, and body aches are also common. Symptoms typically appear 12 to 48 hours after exposure and last for one to three days. Because it spreads so easily, infections can move fast through families and communities.

While most cases improve on their own, dehydration is a concern, so warning signs such as intense thirst or reduced urination should not be ignored, as noted by the Cleveland Clinic.

Do We Have A Norovirus Vaccine?

At present, there is no widely available vaccine for norovirus. That said, research has made meaningful strides. Experimental oral vaccines have shown encouraging results in clinical studies, suggesting they may offer protection against multiple fast-changing strains and help reduce how much virus an infected person sheds. Scientists are hopeful that an effective, broadly protective vaccine may become available in the coming years, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Why Don’t We Have a Norovirus Vaccine Yet?

Developing a vaccine for norovirus has proven especially difficult, largely because of how quickly the virus changes. “It really is evolving extremely rapidly, and that’s a big problem,” Patricia Foster, PhD, professor emerita of biology at Indiana University Bloomington, told Health.

Norovirus also exists in dozens of subtypes, with several dominant strains circulating at any given time. This is why people can catch norovirus more than once in their lives. Even if immunity develops against one strain, either after infection or through vaccination, another strain can still cause illness. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About norovirus.

Norovirus: Multiple Vaccines Are In The Works

Despite these obstacles, vaccine research is moving forward. Progress has accelerated in part because of newer technologies developed over the past decade. In 2016, Mary Estes, PhD, a researcher at Baylor College of Medicine, and her team found a way to grow norovirus outside the human body. This breakthrough made it possible to test vaccine approaches and treatments more effectively. This step was crucial because common lab animals like mice do not typically get sick from human norovirus.

Today, scientists are testing several experimental vaccines. One example is a 2023 vaccine developed at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis that combines protection against norovirus with an existing rotavirus vaccine. Several pharmaceutical companies are also developing candidates, many of which are now in clinical trials, said Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, in comments to *Health*.

HilleVax, a Boston-based company, has been testing a norovirus vaccine originally developed by Japan’s Takeda. However, that candidate did not succeed in a phase II trial in June 2024. Meanwhile, a tablet-style norovirus vaccine from San Francisco-based Vaxart has completed phase I testing. Among the most promising efforts is Moderna’s vaccine, which is currently being tested in human volunteers.

Preventing Norovirus, Even Without a Vaccine

Norovirus spreads so easily that stopping it once someone falls ill can be very challenging. This is linked to the virus’s structure. Norovirus is a nonenveloped virus, similar to polio and other stomach-related infections. Because of this, neither hand sanitizers nor soap and water actually destroy the virus, Foster explained. “Handwashing helps because you’re physically rinsing the virus away,” she said.

As a result, basic hygiene practices, especially thorough handwashing, remain some of the most effective ways to lower risk, said Ming Tan, PhD, an infectious disease researcher and associate professor of pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, speaking to *Health*.

If norovirus does strike, treatment options are limited. Staying hydrated is essential to avoid complications from fluid loss. Some people may also use medicines to control nausea or diarrhea, either over the counter or by prescription, such as Zofran. If severe symptoms develop, including confusion, high fever, or intense abdominal pain, medical care should be sought right away.

Mystery Disease Adenovirus: New Virus Said To Be Stronger Than Covid And Flu — All You Need To Know

Credits: Canva

Adenovirus: A newly emerging “untreatable” mystery virus that is being described as stronger than Covid is now spreading across several parts of the world, with experts warning that even common disinfectants may not be effective against it. Known as adenovirus, the infection causes symptoms similar to a severe bout of flu, such as shortness of breath, a runny nose, and a sore throat. What sets it apart, however, is the limited treatment available.

In most cases, people who contract the virus have no option but to manage symptoms and allow the illness to pass on its own. The good news is that adenovirus infections are usually mild. That said, much like Covid or seasonal flu, the risk rises for people with weakened immune systems, who may experience more serious complications, according to a report by The Mirror.

Jefferson Health’s medical director of infection prevention and control, Eric Sachinwalla, has cautioned that unlike more familiar viral infections, there is very little doctors can do to actively treat adenovirus.

What Is Adenovirus?

Adenoviruses belong to a broad family of common viruses that can affect multiple parts of the body, including the airways and lungs, eyes, digestive system, urinary tract, and even the nervous system. They are a frequent cause of fever, cough, sore throat, diarrhoea, and conjunctivitis. Most infections tend to be mild and clear up on their own within a few days. However, health experts are now noting a rapid rise in cases, with the virus spreading quickly and leaving large numbers of people unwell.

The virus is particularly contagious because it is tougher than many others. Routine cleaning with soap and water or standard disinfectants may not be enough to eliminate it, allowing it to survive longer in the environment. This is why outbreaks are often seen in places such as day-care centres and military barracks, where close contact is common. Adenovirus spreads through respiratory droplets, can be passed through stool, and can linger on contaminated surfaces for extended periods, as per Mirror.

Adenovirus Symptoms

Symptoms of adenovirus infection can vary widely. Common signs include shortness of breath, a runny nose, and a sore throat. Some people may also develop diarrhoea or pink eye. The wide range of symptoms is partly due to the fact that there are more than 60 known strains of the virus.

Adenovirus: How Is Adenovirus Different From Covid And Flu?

Adenoviruses, like coronaviruses, spread from person to person and can trigger similar respiratory symptoms. However, they belong to entirely different virus families and behave differently. One key difference is resistance. Coronaviruses are more easily destroyed by disinfectants, while adenoviruses are harder to kill, which allows them to spread more easily than Covid or flu.

For otherwise healthy individuals who feel unwell but do not have severe symptoms such as high fever or breathing difficulty, recovery usually happens at home with basic supportive care. Medical attention is more important for people with weakened immunity, parents of very young infants, or those with existing conditions like heart or lung disease. If symptoms appear, experts advise against walking straight into a clinic. Calling ahead is safer, as doctors may recommend a telehealth consultation if the illness seems highly contagious.

Adenovirus: Is Adenovirus Untreatable?

Most adenovirus infections are mild and resolve without medical treatment. However, if symptoms linger or worsen, there is often little doctors can do beyond monitoring and symptom relief, as the virus largely needs to run its course. Following basic hygiene measures, such as washing hands regularly and cleaning frequently touched surfaces, remains one of the most effective ways to reduce the risk of infection.

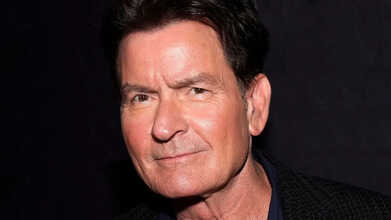

What Is The Experimental HIV Drug Charlie Sheen Says Suppressed The Virus In His Body?

Credits: AP

Though Charlie Sheen’s HIV has been described as “completely manageable,” the actor recently shared that he once came across a treatment he believed worked far better than existing options, but it never reached the public. Speaking on the *Howie Mandel Does Stuff* podcast, the 60-year-old actor reflected on an experimental drug he used years ago and explained why it ultimately disappeared from view. “There was one that was really good that I was hoping would come to market one day, and it never did,” said Sheen, who publicly disclosed his HIV diagnosis in 2015. This has raised a key question: which experimental drug is Charlie Sheen referring to?

What Is HIV?

Human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, is a virus that attacks the immune system. If left untreated, it can progress to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS, which represents the most advanced stage of infection. HIV primarily targets white blood cells, weakening the body’s natural defences. The virus spreads through unprotected sexual contact, sharing needles for drug use, exposure to infected blood, and from parent to child during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding.

What Does HIV Do To A Person?

HIV infects CD4 cells, also known as helper T cells, which play a central role in immune response. As the virus destroys these cells, the white blood cell count drops, leaving the body vulnerable to infections it would normally fight off with ease.

Early on, HIV can cause flu-like symptoms. After that, it may remain hidden in the body for years without obvious signs, while continuing to damage the immune system. When CD4 levels fall very low, or when certain serious infections develop, HIV is considered to have progressed to AIDS.

At this stage, symptoms may include rapid weight loss, severe fatigue, sores in the mouth or genitals, recurring fevers, night sweats, and changes in skin colour.

Charlie Sheen Claims An Experimental Drug That Works Better For HIV

During the podcast conversation, Sheen named the drug he believes made a major difference. “That was a thing called PRO 140,” he said. He described it as a monoclonal antibody that produced faster and more consistent results, with fewer side effects than standard treatments. When asked why it never became widely available, Sheen suggested it may have posed a threat to existing therapies. “It works, better than what they have,” he said, adding that the company behind it ran into serious trouble. Mandel responded that someone should investigate further, a point Sheen agreed with.

What Is The Experimental Drug Charlie Sheen Is Talking About?

PRO 140 is a humanised monoclonal antibody designed to block CCR5, a receptor HIV commonly uses to enter human cells and replicate. Around 70 percent of people living with HIV in the United States, and as many as 90 percent of newly diagnosed patients, carry CCR5-tropic strains of the virus.

Earlier studies found that a single intravenous dose of PRO 140 sharply reduced HIV levels, while weekly injections under the skin lowered viral load much more effectively than a placebo. Research also suggested that the drug did not interfere with normal immune functions linked to CCR5.

According to Aidsmap, PRO 140 was generally considered safe and well tolerated. Although more than 90 percent of participants in extended studies reported side effects, there were no serious adverse reactions linked directly to the drug, and no one had to stop treatment because of it. The reported side effects were limited to injection-site reactions, which were usually mild to moderate.

Sheen has repeatedly spoken about his experience with the drug, maintaining that it delivered steadier results and caused fewer side effects than conventional HIV treatments.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited