- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

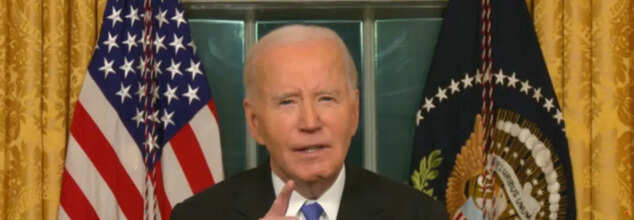

Joe Biden Diagnosed With Nodule In Prostate Gland

Credit: Canva

A small nodule was found in the prostate gland of former US President Joe Biden during a recent physical exam, as per media reports. While not much has been revealed about his medical evaluation, a spokesperson said that the discovery of the nodule "necessitated further evaluation." This comes as British monarch King Charles is already undergoing treatment for an enlarged prostate gland since February last year. Earlier this week, Former Deputy PM of Australia and Nationals MP Barnaby Joyce said that he has been diagnosed with prostate cancer.

While it is quite common for men over the age of 50 to experience prostate problems, the 82-year-old has had a history of medical issues. During his presidency, he had a "cancerous" skin lesion removed from his chest. The White House, in a statement, said that in February 2023, the skin tissue was removed. It was sent for a biopsy, which revealed it to be cancerous.

How To Identify Prostate Cancer?

Prostate cancer is a type of cancer that occurs when malignant cells form in the prostate gland, which is a walnut-sized gland in the male reproductive system. Prostate cancer treatment guidelines have shifted their path a bit in recent years, with many men opting for active surveillance rather than immediate treatment for slow-growing tumours. However, about 50% of men on "watchful waiting" will require further treatment within 5 years because of the tumour progression. This is what triggered many researchers to aim and identify whether dietary modifications, specifically increasing omega-3 fatty acids, could prolong this surveillance period and slow down the tumour progression.

Prostate cancer that's more advanced may cause signs and symptoms such as:

- Trouble urinating

- Decreased force in the stream of urine

- Blood in the urine

- Blood in the semen

- Bone pain

- Losing weight without trying

- Erectile dysfunction

Not All Prostate Issues Are Indicative Of Cancer

Not all prostate problems are indicative of cancer. While prostate cancer is a serious concern, there are other conditions that can cause similar symptoms but are non-cancerous. One common condition is benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Experts state that nearly every individual with a prostate will experience BPH as they age. It leads to the enlargement of the prostate gland but does not increase the risk of cancer. Another condition is prostatitis, which primarily affects men under 50. It is characterized by inflammation and swelling of the prostate, often due to bacterial infections. Early diagnosis can help manage these conditions effectively.

Want a Better Memory? The Answer Lies in Your Sleep

(Credit-Canva)

Finding your keys, remembering a name, or forgetting what you needed at the store happens to everyone. But while it's normal to be forgetful sometimes, it's also important to take care of your memory.

When you're about to learn something new, sleep is a crucial first step. Scientists have found that sleep before you learn actually prepares your brain to take in new information. Without enough sleep, your ability to learn new things can drop by as much as 40%.

This is because a lack of sleep affects a part of the brain called the hippocampus, which is essential for making new memories.

How Your Brain Works to Store Memories During Sleep

After you've learned something, sleep is even more important. When you first form a memory, it's very fragile. Your brain uses sleep as a special time to go back through recent memories and decide which ones to keep.

During the deep stages of sleep, memories become more stable and firm. Research has even shown that memories for skills, like playing a song on the piano, can actually get better while you're asleep. After deep sleep, REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep—the stage where you dream—helps to link related memories together in new and unexpected ways. This is why a full night of sleep can help with problem-solving. REM sleep also helps you process and reduce the intensity of emotional memories.

Link Between Aging, Sleep, and Memory

It's a well-known fact that our sleep patterns change as we get older. Unfortunately, the deep sleep that is so important for strengthening memories starts to decline in our late 30s. A study found that adults over the age of 60 had a 70% loss of deep sleep compared to young adults (ages 18-25). This reduction in deep sleep was directly linked to having a harder time remembering things the next day.

Scientists are now looking into ways to improve deep sleep in older people. Since there are few medical treatments for memory problems in old age, improving sleep could be a very promising way to help people hold onto their memories as they get older. Ultimately, whether you are a student or an older adult, it's important to know that the sleep you get after you study is just as vital as the sleep you get before you study. When it comes to sleep and memory, you get very little benefit from cutting corners.

Some Other Ways To Improve Your Memory

Here are some simple ways you can keep your brain health in check.

Be Active Every Day

Exercise gets blood flowing to your entire body, including your brain. This can help keep your memory sharp. Try to get at least 150 minutes of moderate activity, like walking fast, each week. Even a few 10-minute walks a day can help.

Keep Your Mind Busy

Just like exercise strengthens your body, mental activities keep your brain strong. To help prevent memory loss, try things like reading, doing puzzles, playing games, or learning a new skill or musical instrument.

Spend Time with Others

Being social can help you avoid stress and depression, both of which can lead to memory loss. Make an effort to spend time with friends and family, especially if you live alone.

Stay Organized

When things are messy, it's easy to forget. Use a notebook, calendar, or digital planner to keep track of tasks and appointments. To help remember things, you can repeat them out loud as you write them down. Keep important items like your keys and wallet in the same spot so you can always find them.

Get Enough Sleep

Not getting enough sleep can be linked to memory loss. Aim to get 7 to 9 hours of sleep each night on a regular basis. If snoring or restless sleep is an issue, talk to your doctor, as it could be a sign of a sleep problem.

Eat Healthy Foods

A healthy diet is good for your brain. Make sure to eat plenty of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Also, choose lean proteins like fish and beans. Be mindful of how much alcohol you drink, as too much can cause confusion and memory loss.

Manage Health Problems

Follow your doctor's advice for managing any long-term health issues like high blood pressure, diabetes, or depression. Taking good care of your body can help you take better care of your memory. It's also a good idea to talk to your doctor about any medicines you take, as some can affect your memory.

Is Holding A Grudge Only A Woman's Problem? Science Explains The Gender Difference

(Credit-Canva)

The phrase, “hell hath no fury like a woman scorned” may hold more truth than we led on. Women are always thought of as the less aggressive, more forgiving and expected to be more rational than men. However, how much of that is a biological factor and how much of it is societal expectation?

While many people believe women are more forgiving, the results of many studies suggest otherwise. This 1997 research, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) USA, compared men and women to see if there were differences in how they forgive. The study looked at how forgiving people are in general, as well as how they forgive themselves, others, and situations they can’t control.

Why Women Hold More Grudges

The study, which included 625 people (mostly women), found that men were more forgiving overall than women. Men also showed a greater willingness to move past feelings of unforgiveness. However, when it came to the more positive aspects of forgiveness, like being accepting and compassionate, there was no major difference between the genders.

Both men and women in the study showed similar emotional patterns related to forgiveness. Things like negative emotions, anxiety, and holding in anger were all linked to being less forgiving. On the other hand, positive emotions were linked to being more forgiving. An interesting difference was seen with anxiety control: for women, controlling their anxiety was linked to being less forgiving, but for men, it was linked to being more forgiving.

How Emotions and Gender Affect Forgiveness

The study found that a person's gender can change the way certain emotions are connected to forgiveness. This was especially true for forgiving oneself and forgiving situations that are out of one's control. Forgiveness of others, however, was not significantly affected by these gender differences. This suggests that while everyone's emotions play a role in forgiveness, gender can influence how those emotions shape our ability to let go of certain types of hurt.

Are Men More Forgiving Than Women?

Another 2021 study, published in the Journal of Religion and Health, on average, men were more forgiving than women, especially when it came to overcoming feelings of unforgiveness toward themselves and situations they couldn't control. However, there was no significant difference in the more positive aspects of forgiveness, such as a compassionate mindset.

- The research also found a link between emotions and forgiveness for both genders:

- Negative emotions, like sadness, anxiety, and anger, made it harder for people to be forgiving.

- Positive emotions were associated with being more forgiving.

An interesting finding was how controlling emotions affected men and women differently. For women, trying to control their anxiety was linked to being less forgiving. For men, controlling their anxiety was actually linked to being more forgiving, particularly of themselves and difficult situations.

How Does Serotonin Affect Your Brain?

According to a study published in the Biological Psychiatry, the study showed that when serotonin was low, the connection between two key brain areas became weaker. To find this, researchers adjusted the diets of healthy volunteers to lower their serotonin levels. Using an fMRI brain scan, they observed how the volunteers' brains reacted to faces showing angry, sad, or neutral expressions. They found that these 2 areas of the brain became weak,

- The amygdala, which is the emotional part of the brain that creates feelings of anger.

- The prefrontal cortex, which is the part that helps us regulate and control our emotions.

- This suggests that with low serotonin, it's harder for the prefrontal cortex to manage the anger signals coming from the amygdala. This can make a person more likely to act aggressively.

Why Some People Are More Prone to Aggression

The researchers also gave the volunteers a personality test to see who had a natural tendency toward aggression. They found that in these individuals, the link between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex was even weaker when serotonin was low. This means that people who are already more prone to aggression are the most sensitive to drops in serotonin, which makes it even harder for them to control their angry feelings.

These findings highlight that while everyone's emotions play a role in forgiveness, gender can influence how those emotions shape a person's ability to let go of certain types of hurt.

Miriam Margolyes, Harry Potter Star Shares Honest Health Update 'I've Let My Body Down'

Actress Miriam Margolyes, known for her role as Professor Sprout in the Harry Potter films, recently spoke openly about her health issues. In a new interview, the 84-year-old admitted her lifestyle has taken a toll on her body, which she links to a lifelong struggle with her weight.

When asked about using Ozempic for weight loss, Margolyes firmly rejected the idea, stating, "That’s for diabetics. You shouldn’t take medicine meant for people who are really sick."

Her health struggles have also led to her considering her own mortality. After a recent heart procedure, she shared that she knows she "doesn’t have long left to live," likely within the next five to six years. Despite this, she expressed a strong desire to continue performing, even though she isn't "strong enough" for roles that don't involve a wheelchair.

Miriam Margolyes Health

In May 2023, Margolyes was hospitalized with a chest infection and underwent a heart procedure. She later updated fans on social media, thanking them for their support.

The procedure she had was a Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI), a less invasive alternative to open-heart surgery. On a podcast, she explained that she had an aortic valve replaced with one from a cow. "I’ve got a cow’s heart now," she joked. "I’d never heard of that operation, but it saves you from having open heart surgery."

Beyond her heart issues, Margolyes has also been diagnosed with spinal stenosis, a condition that causes chronic pain and makes it difficult for her to walk. She has registered as disabled and uses a walker and sticks, though she recently got a mobility scooter, which she called "a lot of fun."

Could Heart Health Issues Be Avoided With Exercise?

"I’ve let my body down," she said. "I haven’t taken care of it. I have to walk with a walker now. I wish I’d done exercise." Miriam admitted in the magazine interview. According to the National Institute on Aging, being physically active is pertinent for one’s health.

As you get older, your heart and blood vessels naturally change. While your resting heart rate usually stays the same, your heart may not be able to beat as fast as it used to during exercise or stressful situations.

As you get older, it's not unusual to feel your heart flutter or skip a beat from time to time. Most of the time, this is nothing to worry about. But if you feel like your heart is fluttering or racing very often, or if the feeling doesn't go away, it could be a sign of a heart rhythm problem called an arrhythmia. If this happens, it's a good idea to talk to a doctor, as it might need treatment.

How Does Aging Change Your Heart?

With age, your heart’s size and structure can change. The walls of your heart can get thicker, and its chambers can become bigger. This can make it harder for the heart to hold as much blood as it used to. A thicker heart wall also raises the risk for a common heart rhythm issue called atrial fibrillation, which can increase the chance of having a stroke.

The heart’s valves, which open and close to control blood flow, can also get stiffer and thicker. This can slow down or block the blood flow out of your heart, or they can become leaky. When this happens, fluid can start to build up in your lungs, legs, and feet.

How to Protect Your Heart and Brain

The natural changes in your heart that come with age can increase your risk of heart disease, which can limit your daily activities. It’s also interesting to know that many of the things that are bad for your heart are also bad for your brain. For example, high blood pressure can increase your risk of both heart disease and dementia later in life.

The good news is that you can take steps to protect both. By managing your blood pressure and taking good care of your heart, you are also helping to protect your brain and improve your overall well-being as you get older.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited