- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

‘Miracle Baby’ Born Twice To A Mom With Cancer Mid-Pregnancy; Decoding The High- Risk Surgery

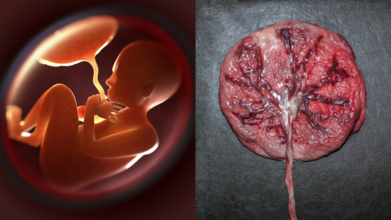

A baby boy in the United Kingdom was born twice—first in the womb and again at full term which was nothing short of an extraordinary medical feat that borders on the miraculous. Meet baby Rafferty Isaac, a symbol of survival, and his mother Lucy, whose determination and courage have moved the world.

For 32-year-old Lucy Isaac, a special needs teacher from Reading, her pregnancy journey took an unexpected turn during a routine ultrasound scan at 12 weeks. The scan revealed signs of ovarian cancer, a diagnosis that would terrify any expectant mother. Waiting to treat the cancer until after delivery was not an option, as the disease risked spreading rapidly. Yet performing conventional laparoscopic surgery during the second trimester was equally out of the question—her pregnancy had already advanced to the point where it complicated standard treatment approaches.

Time was running out. Lucy’s doctors at John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford knew that urgent action was needed to save both mother and child. And so, they turned to an operation that had rarely been performed before—one that would test the limits of surgical precision and maternal strength.

What followed was a pioneering and high-risk five-hour surgery, led by consultant gynecological oncologist Dr. Hooman Soleymani Majd. The procedure involved temporarily removing Lucy’s womb—still carrying her unborn baby Rafferty—from her abdomen. This gave surgeons access to the cancerous tumors growing behind it. Wrapped in warm, sterile saline gauze to maintain body-like conditions, Lucy’s uterus remained connected to vital structures including the uterine artery, cervix, and umbilical cord, while two dedicated medics monitored Rafferty's heartbeat and temperature in real time.

For approximately two hours, Rafferty floated safely outside his mother’s body, held gently by doctors as his mother’s life hung in the balance. Her tumors, diagnosed as grade two, had already begun to invade surrounding tissues, complicating the delicate surgery even further. A surgical team of more than 15—consisting of surgeons, nurses, and anesthetists—worked in unison, navigating the tightrope between preserving life and preventing tragedy.

Despite the enormous risks, the surgery was a success. The tumors were removed, and the womb was carefully repositioned into Lucy’s body to allow the pregnancy to continue as naturally as possible.

Fast forward to January: after weeks of recovery and cautious monitoring, Lucy gave birth to a healthy baby boy, Rafferty Isaac, weighing 6 pounds 5 ounces. For Lucy and her husband Adam, who had undergone a kidney transplant just two years prior, the moment was deeply emotional.

“To finally hold Rafferty in our arms after everything we have been through was the most amazing moment,” said Adam, reflecting on the turbulent journey they had braved together.

Surgeon Dr. Majd, who had only performed the procedure a handful of times before, described the experience as one of the most emotional moments in his career. “It felt as if I had met him previously,” he said, referring to the rare encounter during surgery. Baby Rafferty’s safe arrival symbolized not just survival but a second chance at life.

What Is the Rare Surgery Doctors Performed?

The medical term for the procedure is extra-corporeal uterine surgery, an extremely rare and delicate operation that involves temporarily removing the uterus while preserving fetal life. Though rare, the surgery exemplifies the potential of maternal-fetal medicine when facing dual life-threatening conditions.

Throughout the procedure, maintaining the uterine temperature and blood supply was crucial to preventing fetal distress. The uterus was kept wrapped in warm sterile gauze, and medics ensured constant circulation through the uterine artery. Fetal heart monitoring continued throughout. The team used surgical planning strategies usually reserved for complex oncological operations, paired with advanced obstetric care.

This case also sheds light on how high-risk pregnancies can be managed innovatively through a multidisciplinary approach. It required not only gynecologic oncology but also obstetrics, neonatology, anesthesiology, and surgical nursing teams working seamlessly together.

Lucy considers herself incredibly lucky that her ovarian cancer was detected so early, even before symptoms appeared. Ovarian cancer often goes undetected until its later stages, making early diagnosis critical. According to statistics, approximately 7,000 women in the UK are diagnosed with ovarian cancer each year, and survival rates improve significantly with early intervention.

Baby Rafferty, now eleven weeks old, is thriving—a joyful reminder of how hope, medical innovation, and human courage can intersect to create what some might call a miracle. His story also serves as a beacon of possibility for expectant mothers facing complex diagnoses.

Why Placenta Banking Is Being Called the Ultimate Health Insurance for Families

Credits: Canva

If you thought the only souvenirs from childbirth were baby pictures and tiny socks, times have changed. Turns out, the real treasure might be something most parents never even glance at before it is thrown away: the placenta and umbilical cord. Doctors are now calling placenta banking “biological insurance”, and the idea is picking up pace.

Your Baby’s Placenta Is More Than Just Leftovers

For centuries, the placenta has been treated as medical waste. But according to Dr. D.B. Usha Rajinikanthan, Senior Consultant in Gynaecology and IVF at SIMS Hospital, Chennai, this organ is brimming with stem cells that could be life-saving later on.

“Placenta and cord blood contain stem cells that can repair or replace damaged tissue. Collecting them at birth is safe and painless, but once discarded, that opportunity is lost forever,” she says.

These tiny cells are essentially the body’s master builders, with the potential to transform into different blood and immune cells. Which means what is usually thrown in a bin could actually hold a family’s medical safety net.

Why Stem Cells Are a Big Deal

Stem cells from the placenta are not just versatile; they are generous. Dr. Rajinikanthan explains that they have already been used to treat more than 80 diseases worldwide, including leukaemia, certain immune deficiencies and metabolic disorders. “Research is expanding into conditions like heart repair, brain injury and even diabetes,” she adds.

Placental stem cells are “younger” and more flexible, making them easier to match with siblings and relatives. In simple terms, the baby, siblings, parents and even grandparents may stand to benefit. It is not just your child’s resource; it is potentially a family heirloom.

Placenta Preservation: A Health Insurance

If we insure our cars and houses against accidents, why not our health? Placenta banking works on that philosophy. “It is a one-time investment in future health security. Families may never need it, but having stored stem cells gives enormous peace of mind,” says Dr. Rajinikanthan. She emphasises, though, that choosing an accredited stem cell bank that follows quality standards is essential.

How Does Amniotic Membrane Help?

Beyond the cord blood, there is another underrated star, the amniotic membrane. Dr. A. Jaishree Gajaraj, Head of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at MGM Healthcare, Chennai, explains that the amnion has been saving lives for over a century. “The first use dates back to 1910 when it was applied as a skin graft to promote healing. Today, it is used in ophthalmology for dry eyes, as well as for burns and diabetic ulcers,” she says.

In other words, this part of the placenta is not just a wrapper for your baby; it is a medical toolkit waiting to be tapped.

The Science Behind the Promise

Stem cell science has moved leaps and bounds in recent decades. According to Dr. Gajaraj, the umbilical cord blood and tissue have already been used successfully in bone marrow transplants for children with leukaemia and other bone marrow disorders. But the real buzz is around their future potential.

“These pluripotent cells are being researched for regenerating organs like the pancreas, liver, lungs and even the spinal cord. While still experimental, the promise is extraordinary,” she explains.

She adds that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), particularly those derived from cord tissue, are showing the greatest promise in regenerative therapies. “Foetal MSCs from cord tissue expand better, are less likely to trigger immune rejection, and have higher therapeutic potential than their maternal counterparts,” says Dr. Gajaraj. Simply put, storing placenta and cord tissue maximises the number and types of cells available for future therapies.

But What About Delayed Cord Clamping?

Some parents worry that opting for placenta banking might compromise delayed cord clamping, the practice of waiting a few minutes before cutting the cord to allow extra blood flow to the baby. Dr. Gajaraj reassures that this is not the case. “Delayed clamping does not reduce the yield of mesenchymal stem cells. Parents can safely choose both practices,” she says.

A Gift From Your Newborn to the Whole Family

Placenta banking is not a crystal ball or a cure-all. It does not guarantee immunity against every illness. But as both doctors point out, it offers a shot at future treatments that could transform outcomes in life-threatening conditions

Infant Removed Just Hours After Birth Despite Law Change: Is The Danish Parenting Test Still Separating Families?

(Credit-Ivana Nikoline Brønlund)

In a heartbreaking incident, an infant was removed from the mother, just a mere hour after giving birth after she underwent “parenting competence” tests, despite the new law banning the test.

As the Guardian reports, Ivana Nikoline Brønlund was told she was "not Greenlandic enough" for the new law to apply to her. The social affairs minister for Denmark, Sophie Hæstorp Andersen, has since expressed concern and is asking the municipality to explain its actions, stating that the law on these tests is "clear."

Why Did The Greenlandic Authorities Remove Ivana’s Baby?

The tests, known as FKU, were made illegal for people with Greenlandic backgrounds in May. However, Brønlund, 18, who was born in Greenland to Greenlandic parents, was subjected to a test that began in April and was completed in June, after the law had already taken effect. She was told three weeks before giving birth that her baby would be removed from her care.

Brønlund said she was told her baby was removed because of trauma she suffered from her adoptive father. She says she has only seen her daughter, Aviaja-Luuna, once for a supervised hour, during which she was not allowed to comfort or change her. Brønlund's appeals will be heard on September 16.

This case has sparked protests in Greenland and other cities, with campaigners arguing that it is wrong to punish someone for trauma they are not responsible for. Another similar case involving a Greenlandic mother, Keira Alexandra Kronvold, has also drawn global attention after her baby was removed by Danish authorities.

What Are The Controversial “FKU Test” Danish Parenting Tests?

The FKU, or "parenting competency test," was used by Danish authorities to decide if parents were fit to raise their children. The test was supposed to protect kids, but many believed it was used to unfairly remove Greenlandic children from their homes.

The test used Western ideas of what makes a good parent and was given in Danish. It ignored important parts of Greenlandic life, like their language and culture. Because of this, many Greenlandic parents were misunderstood, and their children were taken away.

Greenlandic children have been a large and unfair part of Denmark's child welfare system. Around 5-7% of Greenlandic children in Denmark were taken from their homes, compared to just 1% of Danish children. Activists believe the FKU test contributed to this big difference.

Why Is the FKU Test Controversial?

Cultural Bias

The test was based on Danish and Western ideas of parenting. It often misunderstood traditional Greenlandic values, like communal childcare and different ways of communicating. This led to parents being judged unfairly.

Unfair Impact

The test had a hugely unfair effect on Greenlandic families. Cases like that of Keira Alexandra Kronvold, whose baby was removed just hours after birth, caused public outrage and protests. These events brought up painful memories of times when families were split up and people were forced to change their culture.

Human Rights Concerns

Human rights groups, including the United Nations, criticized the test for its serious cultural biases. They said the test went against international agreements that require Denmark to protect the cultural identity of Indigenous people.

The Danish government has now promised to make future parental reports more culturally sensitive. However, for families like Keira's, who lost their children because of this test, the change comes too late.

Continued Oppression Of Greenlandic Indigenous Women

While the FKU test is shocking, it is far from being the only case of oppression forced upon them from history. On Wednesday, the leaders of Denmark and Greenland officially apologized for the forced contraception of Greenlandic Inuit women and girls decades ago. This was a dark chapter in their shared history, and both countries admitted their role in the mistreatment.

Between the 1960s and mid-1970s, Danish health authorities fitted as many as 4,500 women and girls in Greenland with intrauterine devices (IUDs) to prevent pregnancies. Many of these women, including teenagers, were not fully informed about the procedure and did not give their consent. This was allegedly done to control the rapid population growth in Greenland at the time.

Last year, nearly 150 of these women sued the Danish government, claiming that their human rights were violated.

How Has The Greenland And Denmark Officials Responded To The Lawsuit?

The Danish Prime Minister, Mette Frederiksen, formally apologized on behalf of Denmark, stating that while the past cannot be changed, they can take responsibility. She said the apology also covers other systematic discrimination against Greenlanders.

Greenland's Prime Minister, Jens-Frederik Nielsen, also acknowledged his country's role and said they plan to offer compensation to the victims. He described the situation as leaving "deep imprints on lives, families and communities."

Although the apology was welcomed and accepted as a big step, but it is noted that the lawsuit is still pending. The apology is seen as a start to repairing the relationship between Denmark and Greenland, which was a Danish colony until 1953 and is now a self-governing entity within the Danish realm. This event is a reminder that the effects of past colonial policies, such as the forced separation of families and forced contraception, still impact people today.

Ozempic Rebound: This Is How Quickly You Could Gain Weight After You Quit Ozempic

Credits: Health and me

You’ve spent months watching the numbers on the scale drop, your clothes fit better, and your energy levels rise. You’ve been consistent with your diet, committed to your workouts, and for many, Ozempic or another GLP-1 medication has been a game-changer. But then life happens—you run out of medication, face insurance hurdles, or decide to stop for other reasons. Abruptly, a question that perhaps had felt far away returns with great haste: how soon will the weight come back?

For those who have been dependent on these injectable weight loss medications, the concept of "Ozempic rebound" may be daunting. It's not about the pounds; it's about restored confidence, preserving improvements in health, and coping with the emotional rollercoaster associated with weight fluctuation. Knowing what occurs in your body when you discontinue these medications—and how you can preserve your gains—may be the difference between frustration and long-term success.

Injectable anti-obesity medications such as semaglutide (brand names Ozempic and Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro and Zepbound) have transformed the treatment of obesity. According to clinical trials, these medications can cause patients to lose 15% to 20% of their body weight on average, in addition to lowering blood sugar levels, improving cardiovascular health, and kidney function. But when you discontinue them, will the weight come back, and if so, how fast?

GLP-1 agonists, the drugs that Ozempic and Mounjaro belong to, mimic an existing hormone known as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). This hormone notifies the brain to be full and satisfied and also slows down the emptying of the stomach. The outcome is decreased hunger, smaller portions, and less desire to eat.

These medications reduce both the physical sensation of hunger and the mental ‘food noise’ that can drive overeating. They essentially recalibrate your body’s hunger signals while you’re on the medication.

The drugs also increase insulin response to food and reduce glucagon levels, helping regulate blood sugar. While taking GLP-1 agonists, the hunger hormone ghrelin is often suppressed, making it easier to maintain caloric restriction without feeling deprived.

What to Expect When You Quit Ozempic?

After you stop using GLP-1 drugs, their hunger-suppressing effects will slowly fade within a few weeks. This can cause increased appetite and faster return of hunger after eating. Patients commonly report returning cravings, sometimes with a sudden intensity that feels like a rebound.

Studies underscore the threat of weight regain. In one study, those who discontinued taking semaglutide and ended lifestyle treatments regained approximately two-thirds of the weight lost within twelve months. The same was noted with tirzepatide, where more than half of the lost weight came back in twelve months.

Weight regain is variable and is influenced by lifestyle behaviors and metabolic changes. Physiology of the body is set up to resist weight loss, and that is why the rebound is so large if there isn't a plan in place.

Even in the absence of drugs, weight rebound is a universal experience. Any meaningful weight loss, regardless of whether it is induced by diet, exercise, surgery, or medication—sets in motion physiological changes like lowered metabolism and enhanced hunger hormones, making maintenance an essential phase.

Easy Methods to Reduce Weight Rebound

Although suspending meds such as Ozempic complicates weight retention, it's not impossible. Professionals suggest implementing organized lifestyle and dietary modifications during ongoing drug use, and these can maintain effects even after being stopped.

Eat a Plant-Forward, High-Fiber Diet

A high-fiber diet enhances satiety, discourages overeating, and maintains a healthy gut. Experts recommend consuming at least 20 to 25 grams of fiber per day from vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and fruits. Plant-based eating also offers a good source of essential micronutrients and aids in controlling cardiovascular risk factors like high blood pressure and cholesterol.

Protein consumption continues to be important, most especially for maintaining lean body mass. Focusing on plant-based protein foods such as beans, lentils, tofu, and quinoa can also serve to control weight while lowering risks from excessive animal protein intake.

Stay Active

Exercise continues to be a weight-loss staple. A study has shown that even modest exercise, like two hours of exercise a week, can reduce weight regain after stopping GLP-1 drugs. Cardio exercises burn calories, and strength training maintains lean body muscle and enhances metabolism.

Prioritize Sleep

Sleep is forgotten in weight control but is an important regulator of appetite. Sleep deprivation may stimulate hunger and diminish satiety, minimizing dietary success. Aim for seven to eight hours of good sleep at night, and create a regular sleep routine screen-free.

Long-Term Approaches to Maintain Results After Quitting Ozmepic

Apart from daily routines, long-term approaches are essential in avoiding rebound weight gain:

Monitor Progress: Use a food diary, measurements, or tracking apps to observe slight changes before they are noticeable.

Seek Support: Frequent visits to healthcare practitioners, support groups, friends, or family can ensure accountability.

Manage Stress: Metabolic alterations and emotional eating can result from chronic stress. Mindfulness, exercise, or therapy can reduce its effect.

Address Underlying Conditions: Illnesses such as hypothyroidism or Cushing syndrome can hinder weight control. Resolving these medical conditions could enhance long-term success.

These strategies applied while still taking GLP-1 drugs can carry forward momentum, making it easier to adjust after treatment discontinuation.

Should You Stop Ozempic?

Whether to discontinue GLP-1 medications is extremely personal. Some patients stop because of side effects like nausea, diarrhea, or constipation. Others encounter financial or insurance issues.

Obesity is a chronic illness linked with elevated risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and some cancers. Interruption of therapy without a formal plan may result in substantial weight regain and return of related health hazards.

Even when patients must or opt to discontinue drugs, it's important to collaborate with healthcare professionals to regulate diet, exercise, and habits. You may also resume the drug later if clinically indicated.

GLP-1 weight loss drugs such as Ozempic and Mounjaro are potent agents for obesity treatment, but stopping them usually results in partial or complete regain of lost weight. The rate and extent of weight regain are determined by several factors such as lifestyle, associated medical conditions, and metabolic changes.

The best prevention strategy for rebound is proactive: eat a high-fiber, nutrient-dense diet, exercise regularly, sleep well, and seek support. Weight loss drugs are not a solution for life, but when used with long-term lifestyle modifications, they can provide long-term health advantages and allow patients to continue progress even after treatment ends

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited