- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

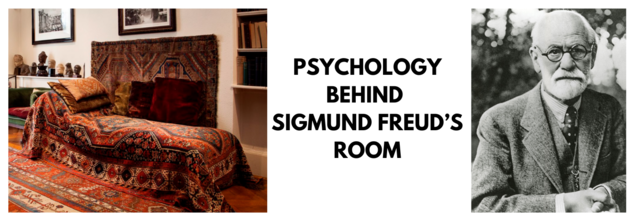

Psychology Behind Sigmund Freud's Room: How Does It Help Patients Even Today?

Credits: Wikipedia and freud.org.uk

Have you noticed how whether it is in the movies, stock images or even in real life, a therapist's office looks similar? They may have different approaches, but the way the space is designed have similarities.

Talking about therapy and psychology, one cannot miss Sigmund Freud and his contributions. For Freud, a space matters and plays an important role in opening up. The human is like a house, it is an exterior and the mind is the interior, like the rooms of the house.

Practising in Vienna, Freud was gifted a couch by a patient Madame Benvenisti upon which Freud added a richly detailed Qashqa'i carpet. He took that with him when he moved to London and kept in the London house to this day.

What Is The Psychology Behind That Chair?

With the carpet placed on top, it gives a non-medical bed look to lie on. Further, the addition of embroidered cushions gives it a rather beautiful and artsy look.

The chair is reclined, and Freud's chair is placed behind, from where the patient cannot see him. This was done purposefully. Eye contact is not conducive to free association, the goal is to let the patient be comfortable enough to start talking loosely.

What Makes It Similar To Other Therapist Offices?

The way this office is designed laid down the foundation for psychological practices to come in the future. Chairs reclined, ensuring the patient's comfort by creating a familiar environment without having to meet the therapist's eyes.

What Does This Do?

It creates a comfortable and relaxed environment for the patient and soft lighting works great with creating a calming environment.

While the structure of the office remained similar, additions like fire extinguishers, first aid kits are also found in the office in case of an emergency. Like Freud's carpet on the couch and on the floor, offices too have non-slip flooring.

Thus a space that is personalised to the therapist's style and needs of their clients can help build a rapport with the patient and put them on ease.

Exposome Explained: How Mapping Humans' Lifetime Environmental Exposure Is Linked To Their Health

Credits: Canva

When Melbourne pediatrician Professor Melissa Wake talks about the future of health, she starts with a sobering fact:

Today's children may live shorter lives than their parents.

It is worth the thought that why despite the medical advances, preventable diseases remain among the biggest killers worldwide.

To this, her response, along with a team of scientists at the Murdoch Children's Research Institute is to launch Generation Victoria.

Generation Victoria is a groundbreaking health study that involves more than 125,000 children and their parents. It is one of the largest projects of its kind and at the core, lies the understanding of exposome.

What Is The Exposome?

It is the some of environmental exposures, including the physical, chemical, psychological, and social. It is what we encounter over the course of our lives, and how they interact with out biology.

It includes tangible factors such as diet, lifestyle, income, education, air pollution, and climate conditions, as well as more invisible elements like chemical pollutants, pathogens, and even noise levels. It also accounts for internal processes influenced by these exposures, such as the microbiome (gut bacteria), inflammation, and metabolic activity.

READ: How Green Therapy Can Help You Lower Anxiety And Depression

"Many of these factors overlap and happen in unequal ways," Professor Wake explains, as is reported by ABC News. "If you grow up in a poor area, your exposome is likely to be shaped by external stressors, polluted air, fewer opportunities, and lower income."

In other words, the exposome is not just about where you live, but how every aspect of your environment, from the air you breathe to the relationships you have, shapes your long-term health.

Why Does Exposome Matter?

Johns Hopkins University researcher Dr Fenna Sillé estimates that up to 70%, and in some chronic illnesses, as much as 90%, of disease risk is linked to environmental exposures rather than genetics.

"If the genome is your biological blueprint, the exposome is the lifelong record of how the world interacts with that blueprint," she says, as is reported by ABC News.

Understanding the exposome could help explain why rates of certain illnesses are rising, even among younger generations. For instance, cancers in Australians under 50 are increasing at what researchers call “alarming” rates. Hypotheses point to factors like obesity, sedentary lifestyles, chemical exposure from plastics, and shifts in gut bacteria due to ultra-processed diets and antibiotic use.

Beyond One Toxin At A Time

For decades, researchers studied environmental health risks by isolating single hazards. For instance, it was focused on one pollutant, one chemical, and observing its effects. But that approach misses the reality of human life, says Dr Nick Osborne, an epidemiologist and toxicologist at the University of Queensland.

"In the real world, there are a lot of exposures happening at once," Dr Osborne says, as is reported by ABC News. "The exposome is about recognizing that the body is a complex system interacting with a complex environment."

Advances in artificial intelligence and computational modelling now allow scientists to process vast amounts of overlapping exposure data, making it possible to see the bigger picture.

ALSO READ: UK Scientists Scan Over 100,000 People, What The Human Imaging Study Could Reveal About Your Health?

How Will This Study Help With Exposome?

GenV is tracking more than 50,000 babies born in Victoria between 2021 and 2023, and their parents, over decades. The aim is to link patterns of exposure with disease risk and test interventions to prevent illness.

The study will collect health data at key stages of life, ages 6, 11, and 16 for children, along with samples such as blood, saliva, and breastmilk. Parents will also share updates on their children’s mental and physical health through an app.

Alongside individual health records, researchers will map “layers” of the exposome. These include family and community-level factors, air quality, climate, built environments, food access, and even shopping patterns. Tools such as satellite mapping, environmental monitors, and policy tracking will help assemble a detailed picture.

The goal is not simply to document exposures, but to act on the most critical ones.

"It would be nice to know everything, but what we really need are the most important things, and we need to act on them," Professor Wake says, as is reported by ABC News.

The long-term nature of the study means researchers can test interventions and see their impact decades later. Could changes in urban design reduce childhood asthma rates? Could improving early nutrition lower lifetime risks of diabetes and heart disease?

READ: How Does Your Lifestyle And Environment Impact Aging?

What Are The Challenges?

The problem comes at the very minute level, it is impossible to capture every detail of a person's environment. However, researchers say that even if partial exposome mapping can uncover meaningful insights, it too is helpful.

Some exposures leave measurable imprints, changes in metabolism, or epigenetic effects, where the environment alters how genes function without changing the DNA sequence itself.

This complexity also means causation is hard to prove. Often, disease risk stems from a mix of genetic predisposition and environmental triggers. As Dr Osborne explains: “You might have the ‘bad’ genes, but if you’re not exposed to the ‘bad’ environment, you don’t get the disease.”

The Human Genome Project, launched in May by an international team Dr Sillé, gave scientists a map of our genetic code. It seeks to do the same for environmental exposures.

If successful, it could transform our understanding of disease prevention, shifting focus from treating illnesses to altering the environmental factors that cause them in the first place.

While GenV’s ambition is to turn exposome data into action. By showing how different life pathways lead to health or illness, it hopes to influence not just medical practice but urban planning, education policy, and food systems.

"We are particularly interested in testing whether we can change disease risk, by how much, and for whom," Professor Wake says. "And because we’ve got that long-term horizon, we should be able to look 20, 30, 40 years down the track."

Can THIS Naturally Occurring Element Treat Alzheimer's

Credits: Canva

A new study published this week in Nature has found that the loss of lithium, which is a naturally occurring element in the brain. This could be an early warning sign of Alzheimer’s disease and a key driver of its progression. Alzheimer’s affects more than 7 million Americans, and this finding offers fresh hope for treatment strategies.

The research, led by Bruce A. Yankner, a professor of genetics and neurology at Harvard Medical School, shows that lithium plays a vital role in maintaining the health of all major brain cell types in mice. When lithium levels in the brain drop, it appears to contribute to nearly all the major forms of brain deterioration seen in Alzheimer’s disease.

While lithium’s link to Alzheimer’s is new, the metal itself has a long medical history, most notably in mental health treatments.

What Is Lithium?

Lithium is the lightest metal found in nature. Silvery and soft, it’s best known today for powering our smartphones, laptops, and electric vehicles, all thanks to its ability to store large amounts of energy and discharge electrons quickly.

Its use in everyday products has an unusual history.

The original version of the soft drink 7Up contained lithium citrate and was marketed as “Bib-Label Lithiated Lemon-Lime Soda,” reported the Washington Post.

Lithium was removed in 1948 after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned its inclusion in soft drinks.

Today, Australia leads the world in lithium production, while Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina form the so-called “lithium triangle” due to their rich reserves.

Lithium’s Role in Mental Health

Lithium carbonate, a chemical form of the metal, has been a cornerstone in the treatment of bipolar disorder since its approval by the FDA in 1970. It is considered a mood stabilizer and is sometimes prescribed for long-term depression management.

Although researchers still don’t fully understand how it works, lithium is thought to reduce stress in the brain and boost neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to adapt and reorganize itself over time.

The new Nature study adds to this understanding, showing that our brains naturally contain small amounts of lithium.

Historically, lithium use in psychiatry dates back to the mid-19th century, but it gained prominence in the late 1940s when Australian psychiatrist John Cade found it helped stabilize bipolar patients.

“It’s been around for decades, and we have a lot of research and evidence supporting its use,” said Elizabeth Hoge to the Post. Hoge is a psychiatry professor at Georgetown University School of Medicine. However, Hoge cautioned that lithium treatment requires regular monitoring of kidney and thyroid function.

ALSO READ: Could Lithium Deficiency In The Brain Trigger Alzheimer’s?

Balwinder Singh, a psychiatry professor at the Mayo Clinic, as reported by the Post, calls lithium the “gold standard” for bipolar disorder, though it is prescribed less often in the U.S. than in Europe. Only about 10–15% of American bipolar patients take lithium, compared with around 35% in Europe. Singh also highlighted its unique benefit: “Lithium is the only mood stabilizer consistently shown to reduce suicidality.”

That said, some research has questioned lithium’s effectiveness for bipolar depression, finding it may not outperform placebos or antidepressants in certain cases.

Why Researchers Are Exploring Lithium for Alzheimer’s

Lithium’s potential role in Alzheimer’s is not entirely new. Past studies have hinted at its protective effects on the brain.

A 2017 Danish study suggested that communities with higher lithium levels in drinking water had lower rates of dementia.

Yankner’s team became interested in lithium after measuring the levels of 30 different metals in the brains and blood of three groups: cognitively healthy individuals, those in the early stages of dementia, and those with advanced Alzheimer’s. Of all the metals tested, only lithium showed a significant difference among the groups.

Lithium appears to help maintain the brain’s “communication network” by supporting neuron connections, producing the myelin that insulates those connections, and aiding microglial cells in clearing cellular debris—processes essential for memory and cognitive health.

How This Could Lead to New Treatments

In lab tests, Yankner’s team administered small amounts of lithium orotate, a different lithium compound, to mice with Alzheimer’s-like symptoms. The treatment reversed the disease model and restored brain function in the animals.

While the results are promising, Yankner stressed that it’s too early for people to start taking lithium for Alzheimer’s. The compound has not yet been tested in humans for this purpose, and lithium can be toxic if improperly dosed.

“This should spur clinical trials,” Yankner said, but he also cautioned that “things can change as you go from mice to humans.”

For now, the research offers an intriguing lead but not an immediate solution. Clinical trials, if launched soon, could take years to confirm whether lithium could safely and effectively slow or prevent Alzheimer’s in people.

A Small Metal With Big Potential

Scientists, now, are beginning to understand that it may also hold a key to protecting the brain from one of the most devastating diseases of our time.

If future studies confirm lithium’s benefits for Alzheimer’s, it could pave the way for a treatment that works by restoring something the brain naturally produces, rather than introducing an entirely foreign substance.

FOMO, JOMO, and Everything in Between: The Social Media–Mental Health Spectrum

Credits: Canva

If your thumb has developed the muscle tone of a professional gamer and your brain twitches when a notification pops up, you are living the full 21st-century social media experience. Somewhere between the fear of missing out (FOMO) and the joy of missing out (JOMO) lies a vast, unpredictable middle ground that can either boost your mood or fry your mental circuits.

FOMO: Anxiety in a Newsfeed

Dr Ashish Bansal, MD, Consultant Psychiatrist and co-founder of House of Aesthetics in New Delhi, describes FOMO as living in “a comparative world”. It is that creeping dread when your feed is flooded with friends on exotic beach holidays, colleagues posting about career wins, or acquaintances showing off culinary masterpieces you didn’t even know could exist.

“This is not just envy,” Dr Bansal explains. “There is a hidden belief that our life is useless when compared with others.” The consequences are more than emotional discomfort; research links excessive FOMO to high stress levels, poor sleep quality, and even depression.

Counselling psychologist Reshmithaa Nair from Sparsh Hospital in Bangalore adds that FOMO “can push individuals to overcommit socially, compare achievements, and feel inadequate.” That compulsive checking of notifications? It is not harmless. It chips away at focus and self-esteem like a relentless digital woodpecker.

JOMO: Peace in the Offline Lane

Then there is JOMO, the Joy of Missing Out, which is less about Netflix marathons in pyjamas and more about a deliberate retreat from the constant online buzz. “JOMO is about setting boundaries,” says Dr Bansal. “Choosing meaningful, offline experiences over endless online engagement.”

It is not an antisocial media rebellion but a conscious decision to protect mental space. Nair points out that people embracing JOMO often experience “reduced stress, improved sleep, and deeper real-life connections”. It is the art of logging off without the guilt, reclaiming your time like a boss, and refusing to measure your worth in likes or retweets.

The Spectrum: It is Not All or Nothing

While FOMO and JOMO are catchy polar opposites, most of us live somewhere in between. Social media is not inherently evil, nor is it a magical self-care tool. It can be a place of connection, learning, and inspiration, or a breeding ground for burnout, envy, and loneliness.

“The impact depends heavily on usage patterns, self-awareness, and boundaries,” says Nair. It is not just about whether you are online or offline, but how you engage when you are there. Dr Bansal calls this mindful usage, curating feeds to highlight uplifting content, scheduling screen-free hours, and remembering that what you see online is “only a highlight reel, not the full story”.

What is Digital Mindfulness?

Digital mindfulness is not about deleting every app and retreating to a cabin in the Himalayas. It is about being intentional. Nair recommends setting clear screen-time limits, pruning your feed to reflect your values, and resisting the urge to scroll aimlessly.Even small shifts, like swapping passive scrolling for purposeful engagement, can turn social media from a mental drain into a growth tool. “When we engage with intention, it can enhance our well-being. When we use it unconsciously, it can amplify stress and comparison,” she says.

From Doomscrolling to Delightscrolling

So what does balance look like in real life?

- Checking updates once or twice a day instead of every 10 minutes.

- Following accounts that inspire you rather than inflame your insecurities.

- Logging off when you feel more anxious than entertained.

It is about catching yourself before you spiral into a 3 am YouTube hole titled “Top 100 Cats Who Look Like Famous Politicians”.

Remember the Offline Reel

Perhaps the most important reminder is that the best moments often do not make it to Instagram. They happen in the middle of unfiltered laughter, over cups of chai with friends, or while watching the sunset without thinking of hashtags. As Dr Bansal says, “Sometimes the best moments are missed while we are just watching a post.”

Nair leaves us with a gentle nudge: “Almost everything will work again if you unplug it for a few minutes… including you.” That means you, your mind, and your phone have an overheating battery. Whether you thrive in the fast-paced digital current, find serenity in switching off, or navigate somewhere in between, the goal remains the same: keep your mental health at the centre of your online habits.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited