- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

What Is 'Butterfly Disease'? The Rare Skin Disorder That Makes Skin As Fragile As Wings

Epidermolysis Bullosa, also known as "butterfly disease," is a rare genetic condition. This congenital disease lets the skin be as fragile as those of butterfly wings. Affected patients can develop painful blisters and sores easily, proving life very difficult to live for all their daily activities. Though its prevalence is extremely rare, estimated to occur in 1 of each 50,000, the impact of this disease on children born with severe forms of the disease is immense.

Although the problems associated with butterfly disease are tremendous, there is a promise of improvement with advancements in gene therapy and other treatments. Research and innovations such as topical gene therapy are bringing new hope for the management of symptoms and possibly curative solutions in the future.

This article delves into the complexities of butterfly disease, including its causes, symptoms, and current developments in treatments, along with essential care tips for managing the condition.

What is Butterfly Disease?

Butterfly disease is a collection of very rare genetic conditions that cause severe skin fragility. Even the slightest pressure or friction from clothing, touch, or minor injuries can cause the skin to tear or blister. The blisters can occur anywhere on the body, including internally, such as in the mouth, gastrointestinal tract, and eyes.

Children with EB are sometimes referred to as "butterfly children" because their skin is fragile, just like the wings of a butterfly. In less severe cases, blisters may primarily occur on the hands, knees, or elbows. In the most severe cases, blistering can be all over the body, leading to scarring, deformities, and even life-threatening complications.

What causes Epidermolysis Bullosa?

EB, butterfly disease, originates from mutations that damage the structure of the skin. These mutations result in broken bonds between layers of the skin and cause separation at stress points. There are 30 different subtypes, but they all fit into one of four larger categories based on where the lesions affect the skin.

The most common subtype, epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS), accounts for about 70% of cases. It is typically inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning a single defective gene copy from one parent can cause the condition. Other, less common forms may require two defective gene copies—one from each parent—making them autosomal recessive.

Symptoms of Butterfly Disease

The symptoms of butterfly disease vary according to subtype and severity. Generally, all kinds of EB share the hallmark feature of fragile skin that blisters and tears easily.

- Blisters on hands, feet, and other pressure-prone areas.

- Scarring and thickened skin in areas prone to friction.

- Blisters can be found internally within the mouth and esophagus, impairing the ability to eat and digest food.

There are severe complications with the more severe forms of EB where blisters form in areas of the eyes, airway, and gastrointestinal tract. Such may lead to conditions such as:

Infections: Open sores are easily susceptible to bacterial infections that may eventually result in deadly sepsis.

Malnutrition and dehydration: Inability to eat due to blisters in the mouth and esophagus.

Risk of cancer: Squamous cell carcinoma is a skin cancer with an increased risk of development.

Life expectancy varies according to the severity. The milder forms of the disease tend to improve with age, while the severe types usually result in early death. Most patients die before reaching the age of 30 years.

Also Read: Smurf Syndrome: Rare Condition That Turns Your Skin Blue-Gray Permanently

Is there a Cure?

Currently, there is no cure for butterfly disease; however, the advancements recently done can offer a much better management system along with improved quality of life.

Gene Therapy

In 2023, the FDA approved a revolutionary gene therapy gel called Vyjuvek. This gel targets dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, a severe subtype caused by mutations in the gene responsible for producing a crucial type of collagen in the skin. Vyjuvek helps heal wounds and prevent further damage by delivering functional copies of the gene directly to affected cells.

- Another remarkable advancement is in developing this gene therapy into an eye drop for vision restoration in EB-related eye scarring.

Other Treatments Involve

- Filsuvez Gel: It is an FDA-approved birch bark gel used to facilitate wound healing in specific subtypes of EB.

- Supportive Care: Pain management, blister drainage, and nonadhesive bandages all contribute to relieving symptoms.

For severe patients, complications may necessitate surgery, including correction of esophageal strictures or deformity due to scar tissue.

Essential Tips for At-Home Care

Caring for butterfly disease needs a lot of attention to prevent complications and ease pain.

- Non-adhesive dressings on the wound with some loose gauze on it.

- Wear loose-fitting, tagless clothes to reduce friction.

- Speak with your doctor about the proper methods to drain blisters safely, to avoid infections.

- Steer clear of heat and moisture; make the environment as cool as possible and bath at room temperature.

- Many patients have deficiencies in iron, selenium, and vitamin D. Consult a nutritionist for suggestions of foods that have these nutrients in them to boost overall health.

- For any of these signs to be red, warm, and pus-filled, seek medical attention as soon as possible if infection is suspected.

Trial of Beremagene Geperpavec (B-VEC) for Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022

The 4 Parkinson's Signs That Appear Years Before Diagnosis

Credit: Canva

Parkinson's disease is a progressive, neurodegenerative movement disorder caused by the loss of dopamine-producing brain cells, primarily affecting people over 60. Apart from motor loss, the disease also causes cognitive decline, depression, anxiety and swallowing problems.

The first symptom may be a barely noticeable tremor in just one hand or sometimes a foot or the jaw. Over time, swinging your arms may become difficult and your speech may become soft or slurred. The disorder also causes stiffness, slowing of movement and trouble with balance that raises the risk of falls.

However, before clear symptoms begin to appear, Neurologist Rachel Dolhun says certain signs may help identify the onset of the disease decades before it is diagnosed.

“It’s important to stress that not everyone who has these symptoms goes on to develop Parkinson’s,” said neurologist Rachel Dolhun. “But we know that in some people, these can be some of the earliest signs," she told The Washington Post.

Here is what you should look out for:

1. Loss Of Smell

Loss of smell, or hyposmia, is a common and early non-motor symptom of Parkinson's disease, affecting up to 90 percent of patients. This symptom can significantly impact quality of life by reducing the enjoyment of food and diminishing appetite.

While strongly linked to Parkinson's, smell loss can also stem from other causes, including sinus problems, COVID-19, or aging.

2. Acting Out Dreams

Acting out dreams, known as REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD), involves physically enacting vivid, often unpleasant dreams through shouting, punching, or kicking during sleep.

This typically happens because the brainstem fails to temporarily paralyze muscles during REM sleep. It is a strong early warning sign of Parkinson's disease, often appearing years or decades before motor symptoms. About 50 percent of people with Parkinson's experience RBD.

READ MORE: Parkinson’s Patients May Soon Walk Better With This New Personalized Brain Therapy

3. Constipation

Constipation is a very common and significant non-motor symptom of Parkinson's disease that is caused by nerve changes slowing gut muscles and potentially exacerbated by low activity and dehydration.

Constipation can also be caused by Parkinson's medications such as anticholinergics, amantadine and other common drugs such as opioids, iron/calcium antacids.

4. Dizziness As You Stand

The autonomic nervous system fails to properly constrict blood vessels or increase heart rate upon standing, often due to a lack of norepinephrine. This causes the autonomic nervous system to fail in regulating blood pressure. Over time, this leads to Neurogenic Orthostatic Hypotension.

Beyond dizziness, symptoms include blurred vision, weakness, fatigue, cognitive "fog," and "coat hanger pain" (pain in the neck/shoulders). Often times, patients experience dizziness in the morning or immediately after meals.

Diagnosing Parkinson’s disease is mostly a clinical process, meaning it relies heavily on a healthcare provider examining your symptoms, asking questions and reviewing your medical history. Various imaging and diagnostic tests used to detect disease includes CT scan, PET scan, MRI scan and genetic testing.

What Is Cold Urticaria? Doctors Warn Of Painful Allergy Caused By Cold Exposure

Credits: Canva

Beyond icy roads and fogged-up car windscreens, the coldest season can also bring on a painful condition that leaves the skin covered in red, itchy patches. Doctors have issued a warning about this lesser-known illness, which tends to worsen in low temperatures.

The condition, known as cold urticaria, affects around one in 2,000 people. It causes swelling and itching of the skin when it comes into contact with cold air, cold water, or even air conditioning. Red welts or hives can appear within minutes, and the discomfort may last for as long as two hours.

What Is Cold Urticaria?

Cold urticaria is an uncommon condition in which the body reacts abnormally to cold temperatures. It typically causes rashes or hives after exposure to cold air, water, food, or drinks. In some cases, symptoms can be more serious. According to the Cleveland Clinic, the condition may sometimes be linked to an underlying blood cancer or an infectious illness.

Griet Voet, head of a dermatology clinic in Ghent, Belgium, as per Express UK, said the condition is often confused with common winter skin problems such as eczema. “This is not just dry skin caused by cold weather, it is a genuine allergic reaction to cold,” she explained. In more severe cases, large areas of the body may be affected, particularly after swimming in cold water or spending extended periods outdoors. This can lead to intense itching, facial flushing, and even headaches, stomach pain, or fainting. Sudden temperature shifts, such as moving from a warm indoor space into cold outdoor air, can also trigger symptoms. Drinking ice-cold beverages may cause swelling of the lips, mouth, or throat.

Cold Urticaria: What Are The Symptoms Of This Disease?

Symptoms of cold urticaria differ from person to person and can range from mild to severe. They may be limited to a small patch of skin or spread across the entire body.

The most common sign is a skin rash that appears after contact with something cold. The rash usually develops once the exposure ends, as the skin begins to warm up.

The rash may include:

- Hives, bumps, or raised welts

- Itching

- Redness

- Swelling

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Headache

- Joint pain

- Fainting

- Heart palpitations

- A severe allergic reaction known as anaphylaxis

- Shortness of breath or wheezing

How Is Cold Urticaria Diagnosed?

A medical professional can often diagnose cold urticaria using a simple test. An ice cube is placed on the skin, usually on the arm, for a few minutes and then removed. If a hive or rash appears several minutes later, the result is considered positive.

In cases of familial cold urticaria, diagnosis may involve exposure to cold air for a longer duration.

Doctors may also suggest blood tests to check for any underlying illness or infection that could be contributing to the condition.

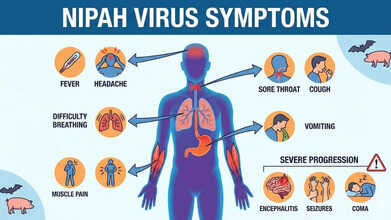

Nipah Virus Symptoms Explained As Doctors Warn Up To 75% Fatality Risk

Credits: AI Generated

Health authorities have urged the public to stay alert to Nipah virus symptoms after doctors warned that up to 75 per cent of infected patients may not survive. The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) has classified Nipah as a “high priority pathogen” because of its severe fatality rate and the absence of any proven treatment.

In India, the federal health ministry has confirmed two cases in the eastern state of West Bengal. This has triggered large-scale containment measures, with local officials placing nearly 200 people who had contact with the infected individuals under quarantine.

Also Read: Vitamin D Supplements Under Scrutiny As It Fails Safety Test

In response, several Asian nations have stepped up airport checks and health surveillance for travellers arriving from India. Professor Paul Hunter, an infectious disease specialist at the University of East Anglia, said identifying Nipah cases at borders is challenging, as symptoms can take a long time to appear.

What Is Nipah Virus?

According to UKHSA, Nipah virus is a zoonotic infection, meaning it can pass from animals to humans. It can also spread through contaminated food or via direct human-to-human contact. The virus was first discovered in 1999 during an outbreak affecting pig farmers in Malaysia and Singapore.

Fruit bats, especially those belonging to the Pteropus species, are the virus’s natural carriers. Research shows that Nipah can also infect other animals, such as pigs, dogs, cats, goats, horses and sheep.

Nipah Virus Symptoms

UKHSA lists the following as common symptoms of Nipah virus infection:- Sudden onset of fever or general flu-like illness

- Development of pneumonia and other breathing-related problems

- Swelling or inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) or meningitis

Symptoms usually appear between four and 21 days after exposure, although longer incubation periods have occasionally been reported. More severe complications, including encephalitis or meningitis, can develop between three and 21 days after the initial illness begins.

Also Read: Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: All That You Need To Know About This Infection

Nipah Virus Symptoms Explained As Doctors Warn 75% Fatality Rate

UKHSA has cautioned that between 40 and 75 per cent of people infected with Nipah virus may die. Those who survive can experience long-term neurological effects, such as ongoing seizures or changes in behaviour and personality. In rare instances, the virus has been known to reactivate months or even years after the first infection.

Nipah Virus: Can You Prevent It From Spreading?

For people travelling to regions where Nipah is known to occur, prevention largely involves reducing exposure risks:

- avoid contact with bats, their habitats, and sick animals

- do not drink raw or partially fermented date palm sap; if consuming date palm juice, make sure it has been boiled

- wash all fruits well with clean water and peel them before eating; avoid fruits found on the ground or those that appear partly eaten by animals

- use protective clothing and gloves when handling sick animals or during slaughter and culling

- maintain good hand hygiene, especially after caring for or visiting ill individuals

- avoid close, unprotected contact with anyone infected with Nipah virus, including exposure to their blood or bodily fluids

Nipah Virus Symptoms Can Be Transmitted Easily?

Many Nipah infections have been linked to eating fruit or fruit-based products contaminated by the saliva, urine or droppings of infected fruit bats. Human-to-human transmission can also occur through close contact with an infected person or their bodily fluids, according to Mirror.

Such transmission has been documented in India and Bangladesh, with cases often involving family members or caregivers tending to infected patients. At present, there is no specific, proven treatment for Nipah virus infection, and no licensed vaccine is available to prevent it.

So far, no Nipah virus cases have been reported in the United States or the United Kingdom.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited