- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

What Is The 'Asian Glow'? Is It Just Body's Reaction To Alcohol Or Something More Dangerous?

Credits: Canva

Commonly nicknamed the “Asian glow” or “Asian flush,” alcohol flush reaction is a physical response to drinking alcohol seen predominantly in people of East Asian descent.

This condition is marked by a reddening of the face, increased heart rate, and sometimes nausea or headaches shortly after consuming alcohol.

About 560 million people worldwide, which makes it roughly 8% of the global population, carry a genetic mutation called ALDH2*2 that causes this reaction. An estimated 45% of East Asians experience flushing when they drink, and many use antihistamines to mask the symptoms.

But researchers warn that these visible reactions are more than just a cosmetic issue, they’re a red flag indicating a heightened vulnerability to serious diseases. We spoke to Dr Gaurav Mehta, Consultant, Gastroenterology/Hepatology and Transplant Hepatology, Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital, Mumbai, who explains that the use of antihistamines (such as diphenhydramine or loratadine) to mask alcohol flush is medically discouraged. These medications may suppress visible symptoms like redness and discomfort, but they do not reduce acetaldehyde accumulation or its systemic toxic effects.

"By concealing early warning signs, individuals may consume more alcohol than they should, leading to increased toxic load, liver stress, and potential long-term complications. Additionally, combining alcohol with antihistamines can impair cognitive and motor functions, increasing the risk of accidents, sedation, and drug interactions," he says.

What Causes It?

The root cause of alcohol flush reaction lies in how alcohol is metabolized in the body.

Normally, alcohol is broken down in two steps.

- First, it is converted into acetaldehyde, a compound far more toxic than alcohol itself.

- Then, acetaldehyde is quickly broken down into acetate by an enzyme called aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2), which the body can safely eliminate.

However, in people with the ALDH2*2 mutation, this second step is impaired. Their version of the ALDH2 enzyme has little to no activity, causing acetaldehyde to accumulate in the bloodstream. This toxic buildup is what leads to the flushing and other symptoms.

The World Health Organization classifies acetaldehyde as a Group 1 carcinogen, meaning there is strong evidence that it causes cancer in humans. Even with moderate alcohol intake, such as two beers, the acetaldehyde levels in people with this mutation can reach carcinogenic levels.

From an oncological standpoint, explains Dr Mehta, this is highly alarming. "Acetaldehyde is both mutagenic and genotoxic it damages DNA, interferes with DNA repair mechanisms, and promotes inflammation, all of which can drive carcinogenesis. The risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is significantly higher in ALDH2-deficient individuals who consume alcohol, even in small amounts."

The danger is further compounded by the fact that these individuals often develop visible flushing reactions, which are frequently misunderstood or dismissed. In many cases, people attempt to suppress the symptoms using antihistamines or continue drinking socially, unaware that they are exposing their bodies to a carcinogenic environment.

Why It’s Dangerous

While many consider alcohol flush reaction an inconvenience, the health risks it signals are far more serious. Experts have linked the ALDH2*2 mutation with significantly elevated risks for several life-threatening conditions if alcohol consumption continues.

Dr Mehta explains, "While this reaction may appear harmless or cosmetic, it is a clinical marker of impaired alcohol metabolism. Persistent exposure to elevated acetaldehyde levels is linked to cellular damage, inflammation, and increased risk for certain cancers. Thus, the flush reaction can indicate a deeper metabolic vulnerability rather than a simple sensitivity."

People with the mutation who drink moderately (defined as two drinks per day for men and one for women) have a 40 to 80 times higher risk of developing esophageal cancer compared to those without the mutation. The risk increases with the amount of alcohol consumed, making it a dose-dependent danger.

The mutation is also associated with higher risks of:

- Head and neck cancers

- Gastric (stomach) cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Stroke

- Osteoporosis

Importantly, these elevated health risks are not seen in non-drinkers with the same mutation, highlighting that alcohol intake is the trigger.

Why Antihistamines Don’t Help

Many young people, particularly college students, take over-the-counter antihistamines like Pepcid AC or Zantac to reduce the visible symptoms of alcohol flush reaction. While these drugs may lessen skin flushing by reducing blood vessel dilation, they do nothing to prevent the dangerous accumulation of acetaldehyde in the bloodstream.

Experts caution that using antihistamines this way is risky. By masking the body’s warning signals, individuals may end up drinking more than they should, unknowingly increasing their health risks.

A Problem of Awareness

Despite the potentially deadly consequences, awareness of the ALDH2*2 mutation remains low.

The variant is believed to have originated from a single individual in Southeast China 2,000 to 3,000 years ago. Today, its prevalence is highest in Taiwan (49 percent), Japan (40 percent), China (35 percent), and South Korea (30 percent). Yet, alcohol consumption in East Asia continues to rise.

Between 1990 and 2017, alcohol use in East Asia increased from 48.4 percent to 66.9 percent. The region now bears the highest burden of alcohol-attributable cancers globally, with 5.7 percent of all cancer cases linked to alcohol, nearly double the rate in North America.

Many people still believe that facial flushing from alcohol is harmless or even a sign of a strong liver. In fact, it’s a clear signal of toxicity and should not be ignored.

Raising Public Education and Health Literacy

Efforts to raise awareness are growing. In Taiwan, researchers and health advocates founded the Taiwan Alcohol Intolerance Education Society, which collaborates with government agencies to educate the public. The group launched National Taiwan No Alcohol Day on May 9, with “5-9” sounding like “no alcohol” in Mandarin, a clever linguistic nudge toward abstinence, as reported by the Washington Post.

Research also suggests that personalized health information can help. A study conducted among Asian American young adults found that those who were informed about their genetic risks related to the ALDH2*2 variant reduced both their drinking frequency and volume over the following month.

Experts emphasize that the message is clear: if you experience alcohol flush reaction, your body is sounding an alarm. Ignoring it may come at a serious cost.

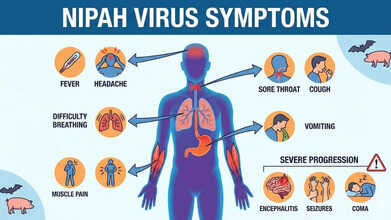

Nipah Virus Symptoms Explained As Doctors Warn Up To 75% Fatality Risk

Credits: AI Generated

Health authorities have urged the public to stay alert to Nipah virus symptoms after doctors warned that up to 75 per cent of infected patients may not survive. The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) has classified Nipah as a “high priority pathogen” because of its severe fatality rate and the absence of any proven treatment.

In India, the federal health ministry has confirmed two cases in the eastern state of West Bengal. This has triggered large-scale containment measures, with local officials placing nearly 200 people who had contact with the infected individuals under quarantine.

Also Read: Vitamin D Supplements Under Scrutiny As It Fails Safety Test

In response, several Asian nations have stepped up airport checks and health surveillance for travellers arriving from India. Professor Paul Hunter, an infectious disease specialist at the University of East Anglia, said identifying Nipah cases at borders is challenging, as symptoms can take a long time to appear.

What Is Nipah Virus?

According to UKHSA, Nipah virus is a zoonotic infection, meaning it can pass from animals to humans. It can also spread through contaminated food or via direct human-to-human contact. The virus was first discovered in 1999 during an outbreak affecting pig farmers in Malaysia and Singapore.

Fruit bats, especially those belonging to the Pteropus species, are the virus’s natural carriers. Research shows that Nipah can also infect other animals, such as pigs, dogs, cats, goats, horses and sheep.

Nipah Virus Symptoms

UKHSA lists the following as common symptoms of Nipah virus infection:- Sudden onset of fever or general flu-like illness

- Development of pneumonia and other breathing-related problems

- Swelling or inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) or meningitis

Symptoms usually appear between four and 21 days after exposure, although longer incubation periods have occasionally been reported. More severe complications, including encephalitis or meningitis, can develop between three and 21 days after the initial illness begins.

Also Read: Nipah Virus Outbreak In India: All That You Need To Know About This Infection

Nipah Virus Symptoms Explained As Doctors Warn 75% Fatality Rate

UKHSA has cautioned that between 40 and 75 per cent of people infected with Nipah virus may die. Those who survive can experience long-term neurological effects, such as ongoing seizures or changes in behaviour and personality. In rare instances, the virus has been known to reactivate months or even years after the first infection.

Nipah Virus: Can You Prevent It From Spreading?

For people travelling to regions where Nipah is known to occur, prevention largely involves reducing exposure risks:

- avoid contact with bats, their habitats, and sick animals

- do not drink raw or partially fermented date palm sap; if consuming date palm juice, make sure it has been boiled

- wash all fruits well with clean water and peel them before eating; avoid fruits found on the ground or those that appear partly eaten by animals

- use protective clothing and gloves when handling sick animals or during slaughter and culling

- maintain good hand hygiene, especially after caring for or visiting ill individuals

- avoid close, unprotected contact with anyone infected with Nipah virus, including exposure to their blood or bodily fluids

Nipah Virus Symptoms Can Be Transmitted Easily?

Many Nipah infections have been linked to eating fruit or fruit-based products contaminated by the saliva, urine or droppings of infected fruit bats. Human-to-human transmission can also occur through close contact with an infected person or their bodily fluids, according to Mirror.

Such transmission has been documented in India and Bangladesh, with cases often involving family members or caregivers tending to infected patients. At present, there is no specific, proven treatment for Nipah virus infection, and no licensed vaccine is available to prevent it.

So far, no Nipah virus cases have been reported in the United States or the United Kingdom.

People Who Began Smoking Before 20 Face Higher Stroke Risk, Study Shows

Credits: Canva

Smoking has long been recognized as one of the most preventable causes of disease and early death worldwide. It plays a major role in heart attacks, strokes and several chronic illnesses. While public health messaging often focuses on how much a person smokes, new research suggests that when someone starts smoking may be just as important for long-term health.

A large nationwide study published in Scientific Reports analyzed health data from over nine million adults in South Korea. The findings were striking. People who began smoking before the age of 20 faced a significantly higher risk of stroke, heart attack and early death compared to those who started later, even if their total lifetime smoking exposure was similar.

Smoking Before 20: Why the age matters

Traditionally, doctors and researchers estimate smoking-related harm using pack-years, which combines the number of cigarettes smoked per day with the number of years a person has smoked. While this remains useful, the new study highlights an important gap. Two people with the same pack-years may not have the same health risks if one started smoking much earlier in life.

The researchers found that early starters had a much higher risk of stroke and heart attack than those who took up smoking after the age of 20. This suggests that the body may be especially vulnerable to tobacco damage during adolescence and early adulthood, making age of initiation an independent risk factor.

Smoking and stroke: what we already know

The link between smoking and stroke is well established. Long-term studies, including the famous Framingham Heart Study, have consistently shown that smokers are far more likely to experience a stroke than non-smokers. The risk increases with the number of cigarettes smoked and affects people across age groups.

Smoking damages blood vessels, speeds up plaque build-up in arteries, raises blood pressure and makes blood more likely to clot. All of these changes increase the chances of both ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes. Younger adults who smoke are not protected simply because of their age, and in many cases, their relative risk is even higher.

Key findings from the Korean cohort

The study followed participants for nearly nine years using data from a mandatory national health screening programme. Researchers looked at stroke, heart attack, combined cardiovascular events and overall death rates.

Those who started smoking before 20 had about a 78 percent higher risk of stroke compared to non-smokers, especially when they also had high smoking exposure. Early starters also showed a much greater risk of heart attacks and combined cardiovascular events. Importantly, they had a higher risk of death from all causes, not just heart-related conditions. These patterns were consistent across men and women and across different metabolic health profiles.

Why early smoking causes greater harm

There are several reasons why smoking at a younger age may be more damaging. During adolescence, the heart, blood vessels and brain are still developing, which may make them more sensitive to toxins in tobacco smoke. Starting early is also linked to stronger nicotine dependence, making quitting harder and often leading to longer periods of smoking.

Early exposure may also trigger lasting inflammatory and metabolic changes in the body. These changes can increase stroke risk later in life, even when total cigarette exposure appears similar on paper.

What this means for public health

The findings send a clear message. Preventing smoking during adolescence could significantly reduce the future burden of stroke and heart disease. School-based education, strong warning messages and policies that limit youth access to tobacco remain critical.

Delaying smoking initiation, even by a few years, may have lifelong benefits. With cardiovascular diseases already among the leading causes of death globally, protecting young people from tobacco use is not just about avoiding addiction. It is about safeguarding their long-term health.

This Simple Tennis Ball Test Can Reveal Dementia Risk

(Credit-Canva)

A simple tennis ball might be able to tell you whether you have dementia or not. While it sounds strange, experts explain that the strength of your hands is a major clue for how well your mind is aging.

In a recent video, Neurologist Dr. Baibing Chen explains that your grip strength is a "window" into your cognitive health. To squeeze your hand, your brain must coordinate nerves, muscles, and blood flow all at once. When this system weakens, it often suggests that the brain’s "resilience" or ability to bounce back is also lower.

While weak hands don't cause dementia, they can be an early warning sign. In some conditions, like vascular dementia, physical changes like slowing down or dropping things often happen before memory loss even begins.

How To Do The Tennis Ball Test At Home?

You don't need expensive equipment to check your strength. You can use a standard tennis ball or a stress ball to track your progress:

Get Ready: Sit up straight with your feet flat on the floor and your arm stretched out in front of you.

Squeeze: Grip the ball as hard as you possibly can.

Hold: Try to keep that strong squeeze for 15 to 30 seconds.

Repeat: Do this three times with each hand and note if you feel tired or if your strength fades quickly.

What the Numbers Mean

Researchers have found that people in the bottom 20% of grip strength have a much higher risk of developing memory problems.

For example, a massive study of nearly 200,000 adults showed that as grip strength drops, the risk of dementia goes up by about 12% to 20%.

Specifically, if a man’s grip strength is below 22 kg or a woman’s is below 14 kg, doctors consider that a "red flag" for future cognitive decline. These numbers are helpful because they show changes in the body years before memory loss actually starts.

What If You Fail The Tennis Ball Dementia Test?

It is very important to remember that a weak grip is not a guarantee of dementia. Many factors, such as arthritis, old injuries, or general lack of exercise, can cause your hands to feel weak.

The goal of this test is not to scare you, but to encourage you to be proactive. If you feel like your hands are getting "tired" faster during daily chores or you are dropping items more often, mention it to your doctor. They can help determine if it is just a muscle issue or something that needs more investigation.

How Is Dementia Diagnosed?

Dementia is one of the most common cognitive conditions in the world. According to the World Health Organization, there were 57 million people living with dementia in 2021, many of whom never had any treatment for it.

Early detection of dementia is an important part of the treatment. While it may not completely cure the disease, it can slow down the progress to help people retain as much of their abilities as possible.

Finding out if someone has Alzheimer’s is not as simple as taking one single test. Doctors act like detectives, gathering many different clues to figure out what is happening in the brain. To make an accurate diagnosis, healthcare providers use a combination of different tools and tests:

Brain Scans

Doctors may use imaging tests like MRI, CT, or PET scans to look at the physical structure of the brain and check for any unusual changes.

Cognitive Tests

There may be cognitive tests that check your recall skills. These are mental puzzles or questions that check your memory, problem-solving skills, and how well you can perform daily tasks.

Lab Work

This can also include blood tests or checking "spinal fluid" to look for specific markers that show up in people with certain types of dementia.

Physical Exams

A neurologist may also check your balance, your senses, and your reflexes to see how well your nerves are working.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited