- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Why Does High Blood Pressure Cause Nosebleeds?

Image Credit: Canva

It was a typical morning. My mother was getting ready; this was her usual routine: bustling around the house. When she suddenly stopped and shouted, blood was oozing from her nose. As kids, my siblings and I were terrified. We scrambled to help, but it wasn't until later that we learned the cause of that alarming moment: high blood pressure. That day was our first lesson in the silent yet powerful effects of hypertension. Nosebleeds, or epistaxis, are common, and nearly everyone experiences at least one in their lifetime.

While most are minor and often caused by dry air or irritation, some can signal underlying health concerns. One recurring question is whether high blood pressure causes nosebleeds or is merely coincidental.

Where Exactly Does a Nosebleed Occur?

The nose is covered by a rich plexus of small blood vessels, making it prone to bleeding. Most nosebleeds are anterior in origin, occurring at the front of the nose, and are relatively benign. They often occur because of irritants such as dry air, frequent nose-blowing, or trauma.

On the other hand, posterior nosebleeds are caused by a source that is located deeper within the nasal cavity. They are less common but more severe, as the blood tends to flow backward into the throat, making them more difficult to control. Common causes of posterior nosebleeds include trauma, medical conditions, or high blood pressure.

Connection Between Nosebleeds and High Blood Pressure

Hypertension is the condition whereby the pressure of blood against the arterial walls is consistently too high. Over time, this may damage the fine blood vessels in the nose, causing them to rupture more easily.

Significant studies have shown a strong relationship between hypertension and severe cases of nosebleeds necessitating urgent care. A certain study showed that patients diagnosed with high blood pressure had 2.7-fold increased chances of having nosebleeds that were not slight.

However, it should be noted that mild hypertension by itself does not cause nosebleeds. Nosebleeds are more likely to happen during a hypertensive crisis when the blood pressure suddenly rises to above 180/120. A hypertensive crisis can also have other symptoms such as a severe headache, shortness of breath, and anxiety. Therefore, it is considered a medical emergency.

Why Does Hypertension Increase the Risk?

Chronic hypertension makes the walls of blood vessels weaker and less elastic, which easily causes them to tear. In the nose, this is especially vulnerable because the blood vessels are close to the surface. Sudden surges in blood pressure, such as in a hypertensive crisis, can cause tears in these weakened vessels, resulting in nosebleeds.

While hypertension is a contributing cause, nosebleeds occur infrequently as the only manifestation of high blood pressure. This makes regular monitoring for blood pressure all the more crucial, as hypertension has the reputation of being the "silent killer" since people often do not present symptoms until the disease has run its course.

Other Causes of Nosebleeds

- Dry Air: Cold weather or house heating dries out membranes that line the nose, hence susceptible to cracking.

- Trauma: Blows in the nose, nose picking or excessive nose blowing can traumatize blood vessels.

- Intrinsic Disease: Liver disease and kidney disease and drug therapy that affect clotting such as blood thinners enhance the risk of nose bleeding.

- Foreign Bodies: Children especially tend to insert objects up their noses, which can be irritating and bleed.

- Allergies or Infections: Chronic nasal inflammation resulting from allergies or colds causes irritation to the nasal mucosa.

Managing Nosebleeds at Home

For most nosebleeds, you can manage them yourself at home:

1. Sit up and lean slightly forward to prevent swallowing blood.

2. Press your nostrils together for at least 10 minutes.

3. Use a cold compress on the bridge of your nose to constrict blood vessels.

4. If the bleeding continues, use a nasal decongestant spray.

Consult a doctor if the bleeding persists beyond 20 minutes, is heavy, or follows a head injury.

Preventing Nosebleeds

Preventive measures can decrease the incidence of nosebleeds:

- Use a humidifier to maintain moisture in the air.

- Apply saline sprays or gels to keep nasal passages hydrated.

- Avoid nasal trauma by being gentle when blowing your nose.

For patients with hypertension, managing blood pressure is the best way to minimize the risk of complications. A combination of lifestyle changes, such as maintaining a healthy diet, regular exercise, and prescribed medications, can help keep blood pressure in check.

When to Worry About Nosebleeds

Most nosebleeds are harmless, but they can sometimes be signs of an underlying health condition. In adults with high blood pressure, frequent or severe nosebleeds should never be ignored. A health provider should be consulted in order to rule out any serious conditions and ensure appropriate treatment.

Regular check-ups, a healthy lifestyle, and awareness about the relationship between nosebleeds and high blood pressure would go a long way to protect your health. Indeed, prevention is always better than cure.

Epistaxis and hypertension. Post Graduate Medical Journal. 1977

Unique Symptoms Of Vitamin D Deficiency

Credits: Canva

Long winters and lack of sunlight has renewed attention on vitamin D deficiency, a condition closely linked to bone health and overall well-being. Health data show that the problem is far more widespread than many realize, with potential consequences that range from brittle bones to mood changes.

Vitamin D and Its Role in the Body

Vitamin D plays a crucial role in helping the body absorb calcium, an essential mineral for strong bones and teeth. Without enough vitamin D, calcium absorption drops, weakening bone structure over time. This increases the risk of fractures, particularly among older adults.

Beyond bone metabolism, vitamin D also supports muscle function and contributes to a healthy immune response. Researchers have also explored its influence on mental well-being, as vitamin D receptors are present in several areas of the brain.

Deficiency Affects a Large Section of Adults

According to figures from the Robert Koch Institute, around 30 percent of adults in Germany have insufficient vitamin D levels. This is striking, given that the vitamin is produced by the body when skin is exposed to sunlight.

Experts point to modern lifestyles as a key reason. Many people spend most of their day indoors, often working in offices with little exposure to natural light. Seasonal factors also play a role, as sunlight is weaker and less frequent during autumn and winter months. In such conditions, relying on sunlight alone is often not enough to maintain healthy vitamin D levels.

Can Diet Help Fill the Gap?

Food can support vitamin D intake, although it usually provides smaller amounts compared to sunlight. Fatty fish are among the best dietary sources. Salmon, herring, eel, tuna, and pike perch contain relatively high levels of the vitamin and are often recommended for people at risk of deficiency.

Other animal-based options include eggs, liver, beef, and butter. For those who avoid animal products, plant-based sources can contribute modest amounts. Mushrooms, spinach, kale, broccoli, and Brussels sprouts are commonly mentioned. Some fruits such as avocados, kiwis, oranges, bananas, and figs are also included in vitamin D-friendly diets, though their contribution is limited.

Read: Vitamin D Supplements Under Scrutiny As It Fails Safety Test

Because many of these foods are eaten infrequently, especially fish, diet alone often fails to correct a deficiency.

Symptoms Linked to Low Vitamin D Levels

Vitamin D deficiency can show up in different ways. Many people report persistent fatigue, low mood, or depressive symptoms. While studies support a connection, researchers note that the exact biological pathways are still being studied.

Physical signs are often related to bone health. Weakened bones can increase the risk of fractures and cause general bone pain. Digestive issues and reduced tolerance to certain foods have also been reported in some cases. A deficiency is usually confirmed through a blood test ordered by a doctor.

When Too Much Becomes Harmful

While deficiency is common, excessive vitamin D intake can also pose risks. Health experts stress that overdoses do not occur through sunlight or normal diets, but through high-dose supplements taken over time.

Too much vitamin D can raise calcium levels in the blood, a condition known as hypercalcemia. This may lead to kidney damage, heart rhythm problems, and calcification of blood vessels. Individual risk varies depending on factors such as body weight, metabolism, and alcohol consumption, making medical guidance essential before supplement use.

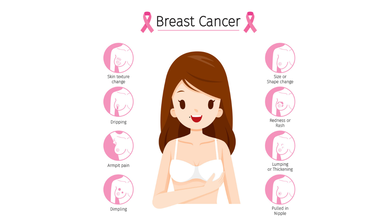

Breast Cancer Signs That Do Not Feel Like Cancer, Explain Doctors

Credits: iStock

On World Cancer Day 2026, we at Health and Me is focussing on the most common cancer among women in India. Breast Cancer, which accounts for over 216,000 new cases every year, as per the 2022 data. This means, 28.2 per cent of female cancers are attributed to breast cancer. What is more tragic is that one woman is diagnosed with breast cancer every four minutes, and one dies every eight minutes in the country.

While, we all know that finding a lump is the red flag, there are other signs that women often miss that delays their detection. Health experts are increasingly warning that this narrow understanding may be delaying early diagnosis for many patients. New medical insights suggest that several lesser-known changes in breast tissue, skin and nipple appearance may signal cancer but often go unnoticed or get dismissed as harmless hormonal changes.

Read: More Than A Diagnosis: Cancer Survivors Share The Small Wins That Helped Them Heal

Breast Cancer Is Not Just A Lump

Data from a consumer survey commissioned by The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center shows that 93 percent of adults identify a lump as a symptom of breast cancer. But fewer than half are aware of several other warning signs that could appear much earlier.

Experts warn that this knowledge gap can be risky because not all breast cancers form lumps that are easily felt. Breast medical oncologist Ashley Pariser explains that screening mammography remains the most effective tool for detecting breast cancer at its earliest and most treatable stages. She adds that being familiar with the normal look and feel of one’s breast tissue helps people detect subtle changes faster and seek timely medical care.

Pariser notes that many breast changes can occur due to aging or childbirth. Still, she stresses that breast cancer can present in multiple ways, making it important for individuals to report unusual symptoms without delay.

Signs That Should Not Be Ignored

According to Dr Kanchan Kaur, Oncoplastic Breast Surgery Specialist, structural changes in the breast are among the most overlooked early warning signs. She highlights that while lumps are common indicators, deformations in breast shape such as flattening, indentation or dimpling should not be ignored.

Read: AI Detects More Breast Cancer Cases in Landmark Swedish Study

Dr Kaur also points out that an unusual increase or decrease in breast size, particularly when it affects only one breast, and sudden changes in breast symmetry may signal an underlying issue. She advises that these signs warrant clinical evaluation even if they appear painless or gradual.

Another concerning sign is skin texture change. She explains that a reddish, pitted texture resembling the surface of an orange or a marble-like area under the skin can indicate deeper tissue abnormalities. Any area of the breast that looks or feels noticeably different from surrounding tissue should be assessed by a doctor.

Nipple Changes Can Be Early Red Flags

Both research findings and clinical observations highlight nipple changes as key indicators that are often missed. Survey results from Ohio State University show that only about one-third of respondents recognized nipple inversion or retraction as a symptom of breast cancer.

Dr Kaur notes that nipples can provide early clues about breast disease. Symptoms such as newly inverted nipples, dimpling around the nipple, scaly red rashes, burning or itching, and ulceration should prompt medical attention.

Read: Oncologists Warns Of The Cancer Rising Among Women in India

Clear or bloody nipple discharge that is unrelated to pregnancy or breastfeeding is another warning sign. While discharge can occur due to benign causes, experts recommend prompt evaluation to rule out cancer.

Specialists at Moffitt Cancer Center caution that symptoms such as breast tenderness, swelling or changes in fullness are often mistaken for routine hormonal fluctuations. Because these symptoms frequently overlap with premenstrual changes, many women delay consulting a specialist.

Experts from the center advise that persistent breast pain, swelling or unusual fullness that does not resolve within a few days should be medically evaluated. They emphasize that sudden nipple inversion, discharge or skin texture changes require immediate attention.

World Cancer Day 2026: India’s 10 Most Common Cancers, Explains Doctor

Credits: Canva

Cancer trends in India are changing rapidly, driven by lifestyle patterns, environmental exposure, infections, and limited access to early healthcare in some regions. According to Dr Puneet Gupta, Chairman of Oncology Services at Asian Hospital, understanding early warning signs and adopting preventive habits can significantly improve survival outcomes.

“Cancer patterns in India are the results of multiple factors ranging from lifestyle, environmental exposure, infections and access to timely care,” Dr Gupta explained, adding that early symptoms can appear months or even years before the disease reaches advanced stages.

Breast Cancer: The Most Common Cancer In Women

Dr Gupta noted that breast cancer is frequently seen in women, especially after the age of 40. He highlighted that the disease often develops silently and without pain.

He explained that warning signs may include lumps in the breast or under the arm, changes in breast shape, skin dimpling, inward turning of the nipple, or unusual discharge. “Do not ignore these changes,” he cautioned. Regular self-examination, along with timely imaging tests such as mammography, ultrasound, or MRI, can help detect breast cancer early.

Cervical Cancer: Strongly Linked To HPV Infection

Cervical cancer mainly affects women between 30 and 60 years. Dr Gupta emphasised that HPV infection remains the leading risk factor. Early symptoms can include abnormal vaginal bleeding, bleeding after intercourse, or persistent pelvic pain, although early stages often remain symptom-free.

He stressed that routine Pap smear screening and HPV vaccination play a crucial role in prevention and early diagnosis.

Lung Cancer: Rising Risk Beyond Smoking

While lung cancer remains more common in men, Dr Gupta pointed out that cases among women are rising as well. Smoking is the primary cause, but exposure to fine particulate air pollution (PM2.5) also contributes to the risk.

He warned that persistent cough, chest pain, breathing difficulty, unexplained weight loss, or coughing blood require immediate medical evaluation, particularly in people with a history of tobacco use.

Oral Cancer: A Major Concern In India

Oral cancer remains widespread due to tobacco, gutka, areca nut consumption, and HPV infection. Dr Gupta explained that long-lasting mouth ulcers, red or white patches inside the mouth, jaw stiffness, or swallowing difficulty are early red flags. Regular dental and oral examinations can help detect early cancerous changes.

Colorectal Cancer: Lifestyle-Linked Risks

According to Dr Gupta, colorectal cancer is increasingly being diagnosed in adults around 40 years of age. Sedentary lifestyles, low-fiber diets, and excessive red meat intake are major contributing factors.

He said symptoms such as blood in stool, persistent bowel habit changes, abdominal pain, or unexplained anaemia should not be overlooked. Early screening and genetic testing in high-risk individuals can significantly improve outcomes.

Stomach Cancer: Often Shows Subtle Symptoms

Dr Gupta explained that stomach cancer may initially present as indigestion, early fullness, nausea, or unexplained weight loss. It is often associated with long-term Helicobacter pylori infection, smoking, and salt-heavy diets. Persistent digestive discomfort warrants medical attention.

Prostate Cancer: Common But Often Slow Growing

Prostate cancer typically affects men above 50 and usually progresses gradually. Dr Gupta noted that difficulty urinating and frequent nighttime urination are common early symptoms. Regular check-ups help detect the disease before complications arise.

Esophageal Cancer: Linked To Lifestyle And Nutrition

Tobacco use, alcohol consumption, poor nutrition, and iron deficiency increase the risk of esophageal cancer. Dr Gupta advised that swallowing difficulty, chest discomfort, or unexplained weight loss should prompt evaluation through tests like endoscopy or barium swallow.

Ovarian Cancer: Often Missed Due To Vague Symptoms

Dr Gupta explained that ovarian cancer frequently goes undetected due to non-specific symptoms such as bloating, abdominal discomfort, or early satiety. Women with persistent symptoms, particularly those with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer, should seek medical evaluation.

Liver Cancer: Screening Is Crucial For High-Risk Groups

Liver cancer often develops in individuals with chronic liver disease. Symptoms such as jaundice, abdominal swelling, or persistent pain usually appear late. Dr Gupta stressed that hepatitis vaccination and screening among high-risk groups are vital for prevention.

Lifestyle Changes And Screening Can Reduce Risk

Dr Gupta emphasized that although cancer cannot be completely prevented, a significant proportion of cases are linked to modifiable risk factors. Avoiding tobacco, maintaining a healthy weight, consuming balanced nutrition, managing stress, and staying physically active can lower risk.

He added that vaccinations against HPV and hepatitis further reduce cancer risk, while regular screening helps detect cancers at pre-cancer or early stages. “Education, prevention and early detection make the difference between late-stage disease and long-term survival,” Dr Gupta concluded.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited