- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

World Mental Health Day: Understanding Addiction As A Disease, Not A Habit

Understanding Addiction As A Disease, Not A Habit

When people think of addiction, the image often conjured is one of recklessness or irresponsibility. Marc Lewis in "The Biology of Desire" explains that addiction rewires the brain’s circuitry, fostering a cycle of craving and compulsion. This means that the addicted brain doesn’t simply “want” substances—it feels as if it needs them for survival. Addiction fundamentally changes the brain’s reward system, making it increasingly difficult for individuals to make rational choices about their substance use.

One of the biggest obstacles to recovery is the stigma surrounding addiction. When society views addiction as a personal failure or a chosen habit, it creates barriers to seeking help. Russell Brand expresses in his book "Recovery: Freedom from Our Addictions", that addiction can take many forms beyond substances, including work, stress, and relationships. There is a universal human tendency to seek external sources of comfort when faced with internal pain. This perspective encourages a more compassionate approach to those suffering from addiction, recognizing that it is not just about the substance or behavior, but about the pain that drives it. The road to recovery is complex, but breaking the cycle is possible with the right tools. David Sheff stresses that understanding addiction as a disease, rather than a moral failing, is crucial to removing the stigma that often prevents people from seeking help.

There are significant and profound impacts addiction can have on individuals, families, and communities. A critical shift in understanding addiction is recognizing it not as a mere weakness, or a bad habit, but as a complex, chronic disease that affects both the brain and behavior. It is not just a matter of choice but a deeply complex disease rooted in brain chemistry, emotions, and social context. This perspective can radically change how we approach treatment, offering a more compassionate and scientifically grounded path to recovery. Understanding addiction as a disease opens doors to new treatment approaches, greater empathy, and more sustainable recovery.

In "Unbroken Brain", Maia Szalavitz reframes addiction as a learning disorder—an interaction between brain chemistry, life circumstances, and learned behaviors that lead to compulsive drug use. She asserts that addictive behaviors fall along a spectrum, much like traits in other neurological conditions, and should be understood as coping mechanisms for underlying issues rather than mere indulgences. It is merely a way to cope with emotional pain.

Addiction is so much more than a habit. Substances alter brain chemistry, particularly in the areas related to reward, motivation, and self-control. Recovery is not simply about choosing to quit.

Addiction hijacks the brain’s prefrontal cortex—the area responsible for decision-making, self-control, and judgment. As a result, people suffering from addiction are often unable to regulate their behavior, even when they want to.

The brain’s reward system reinforces substance use by releasing dopamine, the chemical associated with pleasure and reward. Over time, the brain becomes dependent on this chemical surge, leading to tolerance (needing more of the substance to feel the same effect) and withdrawal symptoms when the substance is not available.

Acknowledging addiction as a disease requires a holistic, multi-faceted approach to treatment—one that addresses the psychological, biological, and social factors that contribute to its onset and perpetuation. It is important to understand the emotional drivers and triggers behind addictive behaviors. Viewing addiction as a disease, rather than a habit, opens the door to more effective, compassionate, and comprehensive treatment.

It is important to challenge outdated narratives and promote a more nuanced understanding of addiction.

In practice, this means that treatment should extend beyond simply detoxifying the body from substances. It should encompass therapy that helps individuals understand the emotional and psychological reasons behind their addiction. Additionally, support systems—family, group therapy, or peer support groups—are critical in sustaining long-term recovery.

Apps like letsgethappi give people access to cognitive tools for managing cravings, stress, and emotional triggers. This kind of digital support is a game-changer, especially for those who may not have immediate access to in-person treatment or prefer more discreet care options.

Viewing addiction as a disease rather than a habit shifts the focus from blame to understanding. It encourages us to approach addiction with empathy, knowing that it is rooted in deep neurological and emotional mechanisms. When we break free from the idea that addiction is a mere choice, we open the door to more effective treatment and, ultimately, a healthier society.

Whether through innovative therapies, supportive apps, or community-based programs, the path to healing begins with understanding addiction for what it truly is—a chronic disease that requires care, patience, and resilience. Only by breaking this cycle can we offer those struggling with addiction the opportunity to reclaim their lives.

Scabies Cases Rise Across The UK This Winter: Know The Early Symptoms

Credits: AI Generated

England is recording higher-than-normal scabies infections this winter. Health authorities have cautioned that the condition, caused by microscopic mites known as Sarcoptes scabiei that tunnel into the skin, spreads quickly through close physical contact and often leads to severe itching and irritation. Data from the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Research and Surveillance Centre shows scabies is circulating more widely than usual in England, with cases increasing through the autumn and winter months.

Also Read: Doctor Explains Why Weight Loss Drugs Like Ozempic Are Truly A Medical Breakthrough

Scabies UK: What Is Scabies?

Scabies is caused by the Sarcoptes scabiei mite. These tiny parasites burrow beneath the skin where they survive, feed and lay eggs. The presence of the mites triggers an allergic reaction in the skin, resulting in an itchy rash. Scabies passes easily from one person to another, particularly among people living in close quarters.

If one member of a household is infected, doctors usually advise checking and treating other family members and close contacts at the same time, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Scabies UK: What Are The Early Symptoms Of Scabies?

Early signs of scabies include intense itching, which is often worse at night, along with a pimple-like rash, small blisters, and thin, irregular lines on the skin known as burrows. These symptoms commonly appear between the fingers, on the wrists, elbows, armpits, waist and genitals. According to the National Health Service, these reactions occur due to the body’s response to the mites and their eggs beneath the skin.

Symptoms do not usually appear straight away and may take three to six weeks after the initial infection to develop. However, people who have had scabies before may notice symptoms within a few days. Typical signs include severe night-time itching and small bumps, blisters or burrow-like tracks on areas such as the hands, wrists, elbows, nipples, genitals and waist.

In more severe cases, the skin may become thickened, rough and scaly. Among children and older adults, scabies can also affect the scalp, face or the soles of the feet.

Scabies UK: Are There Different Types Of Scabies?

Yes, scabies exists in several forms beyond the classic type. These include:

- Crusted (Norwegian): This form is more likely to affect people with weakened immune systems. It causes thick crusts over large areas of skin and can involve millions of mites, compared with the 10 to 15 mites typically found in classic scabies.

- Nodular: More commonly seen in children, this type affects areas such as the genitals, groin or armpits. Firm, raised lumps may persist even after the mites have been eliminated.

Scabies UK: How Is Scabies Treated?

Scabies is usually treated successfully with prescribed medicated creams and lotions called scabicides, along with careful hygiene measures. To avoid reinfection, clothes, bedding and towels should be washed at high temperatures and tumble-dried or ironed. Items that cannot be washed should be sealed in a bag for at least three days, as the mites cannot survive without contact with human skin.

Professor Michael Marks, a professor of medicine at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and former chair of the International Alliance for the Control of Scabies, said the rise in cases may be linked to delays in accessing medical care and gaps in identifying and treating close contacts, which can allow the infection to continue spreading.

Doctor Explains Why Weight Loss Drugs Like Ozempic Are Truly A Medical Breakthrough

Credits: iStock

Ozempic, Mounjaro, Wegovy, and many more such popular weight loss drugs are now making headlines. They are also dominating social media, dinner table conversation and many more. But, is Ozempic truly a medical breakthrough, a miracle drug? Dr Shubham Vatsya, a gastroenterologist, and hepatologist at Fortis Vasant Kunj explains how did this drug change the weight loss struggle that many people face.

Why Is GLP-1 Drug A Medical Breakthrough?

Dr Vatsya explains that it took 20 years of research for scientists to come up with these medicines. This drug underwent proper lengthy trials, and have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), "which is not obtained by giving any bribe".

Also Read: Fact Check: Is Weight Lifting Safe for Teens? An Expert Explains the Risks and Safer Alternatives

He also noted that when a person is not able to lose weight, Ozempic and drugs alike give a "head start" to them, along with a hope.

Talking about side effects, he says that every drug has its side effects, this is where a doctor's role comes in.

"Now, the person who is not able to lose weight, if you tell him 'you hit 100 kg bench press', he will break his shoulder. He needs a kickstart somewhere. This is what weight loss drugs allow," he says.

He also points out that the scientists who made GLP-1 agonists got a Nobel Prize, which "cannot be a scam". This is what makes weight loss drugs truly different.

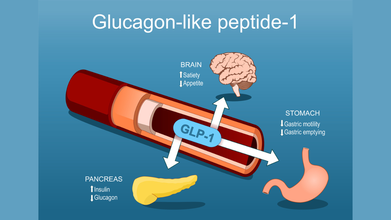

What Are GLP-1 Drugs?

GLP-1 Drugs stand for Glucagon-like peptide 1, a naturally occurring hormones that helps regulate blood sugar and appetite after eating. It was first identified almost 50 years ago and scientists have since uncovered its role in type 2 diabetes.

Almost two decades of research went behind it that led to the development of GLP-1 agonists. It was in 2005, when the first GLP-1 medication, exenatide was approved.

Read: Could You Become Addicted To Your Weight Loss Drugs?

These medications have three main functions:

- Stimulating the pancreas to release insulin

- Slow the transit of food in the stomach to help people feel fuller for longer after a meal

- Act on areas of the brain that regulates hunger and fullness, leading to smaller portion sizes and reducing cravings

Popular drugs like Ozempic and Wgovy, which have semaglutide, which is a GLP-1 receptor agonist, or tirzepatide found in Zepbound and Mounjaro are FDA-approved for type 2 diabetes and weight loss.

These drugs work by binding GLP-1 receptors in the body, which in return increase insulin production in response to food intake and suppress glucagon, a hormones that raises blood sugar.

Also Read: How Weight Loss Drugs Change Ones Relationship With Food?

Are The Popular Weight Loss Drugs Addictive?

There is currently no data suggesting that GLP-1 medications cause physiological addiction. Interestingly, some research suggests they may even reduce cravings related to alcohol or opioid use. That directly contradicts the idea that these drugs hijack the brain’s reward system in a traditional addictive way.

Still, wanting or feeling unable to stop a medication because of fear of weight regain or loss of control is very real. That experience should not be dismissed, even if it is not addiction in the clinical sense.

These medications are meant to support long-term habit change, not replace it. Nutrition, movement, sleep, and a healthier relationship with food are meant to develop alongside the medication. When people reach their goal weight, doctors may suggest tapering the dose slowly or moving to a lower maintenance schedule rather than stopping abruptly.

Stopping suddenly can make hunger feel overwhelming. A gradual transition allows the body and mind time to adjust. Some people do successfully maintain weight loss without the medication, but it usually requires strong lifestyle foundations first.

Going Through Cough And Flu? NHS Issues Urgent Cough Syrup Warning

Credits: Canva

As cough and flu season sweeps across the UK, health expert Dr Xand shared crucial guidance during today’s episode of BBC Morning Live (Jan 19) for anyone struggling with a stubborn cough. The discussion focused on coughs and colds, highlighting new research showing that human rhinovirus, a common cause of cold, can also trigger pneumonia in adults.

Flu Season In UK: Warning Signs To Watch For

Speaking with presenters Helen Skelton and Gethin Jones, as per Mirror, Dr Xand, a specialist in public and global health, explained which symptoms indicate a cough should not be ignored. He noted that a persistent cough is one of the key signs of pneumonia.

Gethin asked, "A cough happens with many illnesses, so when should someone really worry?" Dr Xand replied, "This is a big question, and plenty of people at home might be thinking, 'Is this serious?' because coughs can linger for a long time."

He continued: "Viruses like respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) can cause what’s known as the 'hundred-day cough,' and people can be coughing for weeks wondering what’s going on."

Dr Xand advised viewers to follow the NHS guidelines for coughs, saying, "The NHS recommends consulting your doctor if a cough persists for over three weeks. Many coughs last three to four weeks, and you’ll usually notice if they’re improving. Right now, the most common cause is a virus."

Dr Xand’s Cough Syrup Alert

Addressing people from home about cough syrups, Dr Xand highlighted the latest NHS guidance. He suggested trying more natural remedies, which can be just as effective. "The NHS does not actually recommend cough syrup," he explained. "It advises hot lemon with honey instead."

The official NHS website confirms that "hot lemon with honey has a similar effect to cough medicines." This simple remedy can soothe the throat, calm irritation, and reduce the cough reflex. Some studies even suggest it works as effectively as certain over-the-counter medicines, particularly for children over one year old. However, it’s important to note that it doesn’t treat the underlying illness.

What Do Cough Syrup Studies Show?

Research shows that most over-the-counter cough medicines offer minimal benefits. Studies, including those from the Cochrane Collaboration, reveal that they perform little better than a placebo for short-term cough relief in both adults and children.

While these syrups may temporarily ease throat irritation or provide a sense of relief, ingredients such as dextromethorphan and guaifenesin often do no better than sugar pills. Much of the perceived benefit comes from the placebo effect or the body’s natural recovery.

Instead, simpler measures like honey, staying hydrated, and using painkillers such as paracetamol or ibuprofen are often more effective. Most coughs caused by colds simply need time to resolve.

Cough Syrup: Red Flags To Watch For

Dr Xand shared the warning signs people should be aware of. "There are several red flags worth noting. High fever, chills, or unexplained shortness of breath are all reasons to see a doctor immediately. You should be able to breathe normally, and if you can’t, that’s a concern."

He added, "Any chest pain with a cough, very thick mucus, or extreme fatigue are also serious signs. More severe warning signals include trouble breathing, bluish lips or fingertips, confusion, mental changes, prolonged high fever, and a rapid heart rate."

"It’s crucial to act quickly," Dr Xand continued. "I’ve seen cases in my own family where someone went from a mild cough to being extremely unwell in just a day. Sudden deterioration can be life-threatening, so early medical help is essential."

Pneumonia Can Be Subtle but Serious

Dr Xand emphasized, "Pneumonia can sometimes develop quietly. It isn’t always dramatic, but it can be fatal. That’s why it’s so important to monitor symptoms and seek medical help promptly if things are getting worse."

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited