- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

World Misophonia Awareness Day 2025: Why Misophonia Makes Everyday Sounds Feel Like An Attack—Here’s What It Does To The Brain

Credits: Health and me

You're at the dinner table and someone slurps soup, another begins tapping a pen, and your heart begins racing, your muscles lock up, and you're filled with fury you can't explain. If this sounds familiar, you're not being "too sensitive." You may be one of millions dealing with misophonia, a little-understood sensory disorder finally receiving long-overdue notice.

On July 9, World Misophonia Awareness Day, experts and advocacy groups are urging for global recognition of this condition that impacts almost 1 in 5 adults, but too often remains misunderstood or undiagnosed. Initiated by non-profit soQuiet, the day is dedicated to advancing discussion, research, and support for those whose lives are deeply affected by what the rest of us tune out—usual, ordinary sounds.

What Is Misophonia?

Misophonia, literally "sound hatred," is more than not liking noise. It's an intense, automatic emotional and physical response to certain sounds, usually created by someone else. Chew, sniffle, heavy breathing, throat clearing, even pen clicking.

These stimuli trigger strong reactions in individuals with misophonia, from annoyance, stress, and revulsion to outright panic or fury. For some, it's a single stimulus. For others, it's multiple. The psychological weight can be overwhelming, so that everyday encounters such as dining at a restaurant or working in an open office become a daily war.

And though most people write it off as being irritable or melodramatic, the science disagrees.

An increasing amount of research is revealing what's actually going on in the brains of individuals with misophonia. A 2022 study published in Frontiers in Neuroscience indicates that misophonia is potentially associated with a specific "neural signature"—unique brain pathways that are more active in perceiving sound and emotion.

In misophonics, increased interconnectivity between the sound-processing auditory cortex and the emotion-regulating limbic system may be what makes some sounds ring alarm bells. It's a brain in overdrive, responding in the same way to a throat clear or chewing noise as it would to a bodily threat.

A reflexive fight-or-flight response—hands sweat, heart throbs, and logical thinking yields to a frantic need to flee or strike out.

Why Misophonia Is Unheard And Misunderstood?

Perhaps one of the most infuriating things for people with misophonia is that others just don't get it. It doesn't help that they are invisible and their reactions are usually termed overreactions, even rudeness.

Worse still, it has the potential to overlap with or be confused with other mental illnesses such as OCD, anxiety, PTSD, or even autism spectrum disorders. That is why diagnosis becomes complicated and many suffer silently, particularly older people who might have spent decades without ever hearing the term "misophonia."

The stigma may result in isolation, strain on relationships, and depression, particularly when individuals are stuck in environments where they cannot escape to be safe from trigger sounds—such as school, work, or home mealtime.

Misophonia is not just about being uncomfortable—it's about survivability. Most with the condition report avoiding parties, leaving jobs, or having trouble with day-to-day activities just to prevent exposure to triggers. Picture wearing noise-canceling headphones just to get through your workplace. Or having every meal in solitude, because even the sound of eating is too much. In a world that's getting noisier, adaptation is a full-time profession.

How Misophonia Affects the Brain?

Misophonia's not so much about what you're hearing—it's about how your brain interprets that sound. New research indicates that individuals with misophonia exhibit heightened activity and connectivity within brain areas that handle sound processing, emotional control, and the body's defense mechanism.

One of the most important regions engaged is the anterior insular cortex, which assists you in assessing the emotional meaning of sensory input. In misophonia, this region seems to hyperreact, sending messages that something harmless—such as someone chewing—is threatening. This activates the limbic system, which controls emotion and survival reactions, placing the individual in a fight-or-flight state very quickly.

Imagine it like a smoke alarm blaring at burnt toast like it is a raging house fire. That exaggeration is what makes misophonia so debilitating. A person with misophonia has a complete body stress response when they hear a trigger sound, even though rationally, they know the sound is not harmful.

Brain imaging studies suggest this is not about overreacting by choice—it’s a neurological mismatch, where emotional and auditory systems are too tightly wired together. That’s why even brief exposure to trigger sounds can feel unbearable and linger long after the sound stops.

Common Trigger Sounds of Misophonia

Misophonia triggers are different for different people but most follow predictable patterns. They're not loud or startling noises—they're typically repetitive, mundane sounds easily tuned out by other people but for the misophonic person, which can trigger an almost immediate adrenaline rush of anger, panic, or disgust. The following are the most typical categories of trigger sounds:

Drinking and eating noises: Smacking lips, slurping, chewing, gulping, crunching, and loud swallowing are the worst. Chewing gum is a very frequent offender.

Sounds associated with breathing: Sniffling, heavy breathing, nose blowing, or snoring are common culprits. Even a faint wheeze can be offending for some.

Sounds of the mouth and throat: Throat clearing, coughing, yawning, or audible kissing sounds.

Repetitive sounds of activity: Tapping on the pen or feet, mouse clicking, typing, drumming fingers, or even paper or plastic bag rustling.

Environmental and ambient sounds: Ticking clock, ringing telephone, dripping water, or sounds of animals such as barking.

Surprisingly, several individuals comment on how the proximity or origin of the noise is important. A TV chewing noise might be mildly annoying—but if it's coming from someone sitting directly next to them, the response can be volcanic. This serves to illustrate that misophonia is not about the sound type or volume but also relationship, context, and physical proximity.

Knowing these triggers can inform treatment and coping mechanisms, particularly when seeing therapists and learning to recognize patterns and decrease emotional reactivity over time.

Is Misphonia Treatable?

Misophonia is finally being studied, understood, and treated. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is showing promising results. A 2020 study published in Depression and Anxiety found that more than a third of patients undergoing CBT saw a meaningful reduction in misophonia symptoms—and these improvements held up a year later.

CBT involves finding individual noise triggers and reframing the emotional response to them. It's training the brain to break the anxiety or anger spiral, not allow it to get the best of you. In extreme cases, therapy is also paired with anti-anxiety medication to decrease reactivity, particularly when CBT alone doesn't work. Other coping strategies are:

- Wearing noise-canceling headphones

- Using white noise machines or soothing background music

- Deep breathing or muscle relaxation exercises

Why is Family and Social Support Important?

For individuals with misophonia, having family members know what the condition is and what it's like makes a huge difference. Family members tend to unwittingly become trigger points—chewing at the dinner table, throat clearing, playing music out loud.

Dismissal and blame only exacerbate the emotional toll. Specialists maintain that education and compassion are essential. Accepting that the response is involuntary—and not a personal affront—is critical. Offering professional assistance and using supportive measures in the home can assist in creating safe, respectful spaces for those affected.

World Misophonia Awareness Day isn't only for patients—it's for everyone. By recognizing that some sensory stimuli can be triggering, offices, schools, and public places can start to make changes that are inclusive.

Misophonia isn't a trait, it's a real, life-changing condition that's worthy of attention and understanding. As the research expands and the stories get out there, we get closer to a world where individuals with misophonia don't merely exist—but thrive.

51-Year-Old Neurologist Loses 30 Kg: Shares His Life-Changing Weight Loss Secrets

(Credit- Dr Sudhir Kumar MD DM/X)

It is truly never too late to turn your life around and find a better version of yourself, and this neurologist is proof of that. Although you may have heard of many weight loss stories, where people overcame many difficulties and lost multiple kgs, it can be a much more difficult task to find that motivation yourself.

From 100 kgs to 70 kgs, Dr Sudhir Kumar shared his weight loss journey on social media platform X. He shared his experience and realistic tips that helped him lose the extra pounds and take a step towards a healthier future.

How Dr Sudhir Kumar Lost the Weight

Dr. Kumar's journey started in November 2020. At that time, he had some habits that weren't great for his health: he worked long hours (16-17 per day), got very little sleep (4-5 hours), and ate a lot of junk food and sweets. He weighed 100 kg and found it difficult to even walk 5 km.

To start his transformation, he focused on a simple exercise: running. But he didn't jump into it all at once. He began slowly by walking 5 km, and over the next few months, he gradually increased his distance to 10 km. After that, he started jogging and then running. His main goal was to focus on the time he spent being active, not how fast he was.

How Did Losing Weight Helped Dr Sudhir Kumar?

Later, in December 2022, he also added strength training at least three times a week to build muscle and burn more calories. These lifestyle changes led to some incredible results, both on the scale and in his overall health.

- He went from weighing 110 kg down to a healthy 70 kg.

- He felt more awake and focused at work and had more energy throughout the day.

- His resting heart rate dropped from 72 beats per minute to a much healthier 40-42 bpm, showing how much stronger his heart had become.

- His blood sugar, cholesterol, and blood pressure all got better, reducing his risk for many serious health problems.

- He also noticed a boost in his self-esteem and self-confidence.

What Are Dr Sudhir Kumar's Top Weight Loss Tips?

Dr. Kumar shared the most important lessons he learned, hoping they will inspire and guide others.

- The most important thing is to show up and be active every single day. Being consistent is more important than working out at a high intensity.

- Run at a pace that you enjoy, not one that competes with others. Your speed will naturally get better over time as you get fitter.

- Don't just stick to running. Adding other activities like strength training or cross-training will keep you from getting bored and help prevent injuries.

- Exercise works best when you also change what you eat. Focus on reducing your total calories and try eating within a specific time window each day.

- Getting 7-8 hours of sleep is non-negotiable. Good sleep helps your body recover, improves your mood, and gives you the energy you need for your workouts.

- Dr. Kumar reminds everyone that these are just helpful tips, not strict rules. He strongly advises talking to a doctor before making any big changes to your diet or exercise routine.

Gamer’s Neck Develops 'Dropped Head Syndrome' After Years Of Looking At His Phone, Doctors Warn Of Debilitating Condition

Credits: JOS Case Reports

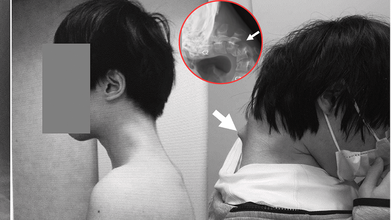

When was the last time you caught yourself hunched over your phone, neck bent at an unnatural angle? A few minutes scrolling might feel harmless, but for one 25-year-old gamer in Japan, years of that posture ended with a shocking diagnosis, “dropped head syndrome.” His story has left doctors urging young people worldwide to rethink how long they spend staring down at their screens.

In a striking case that has unsettled health experts, Japanese doctors documented how a 25-year-old man grew a serious case of "dropped head syndrome" after years of crouching over his smartphone playing video games. The debilitating but unusual condition left him unable to lift his head, properly swallow food, or sustain a healthy weight.

In the case report released in JOS Case Reports in 2023, the patient's battle started following years of isolation from society in his teenage years. Having endured constant bullying at school, he isolated himself in his bedroom and spent many hours glued to his phone playing games, with his head leaning forward at steep angles for hours on end.

How Smartphone Overuse Weakened His Neck?

The injury was chronic. For six months, the man suffered from excruciating neck pain before he lost all ability to lift his head. His vertebrae deformed and dislocated over time, scar tissue in his spine formed, and he had trouble swallowing, leading to spectacular weight loss.

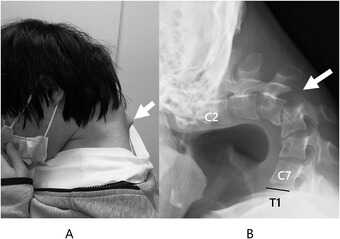

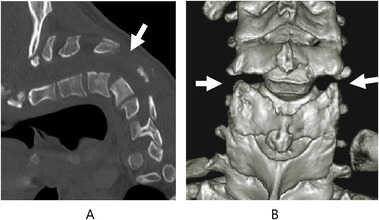

Scans established that his cervical spine had been subjected to extreme stress through unnatural posture over many years. The muscles and ligaments that were meant to keep the head upright no longer worked, and his chin would sag onto his chest.

The doctors first tried to treat it conservatively using neck collars, but the patient complained of numbness and pain, compelling the team to embark on surgery.

How Did The Doctors Treat 'Dropped Head Syndrome'?

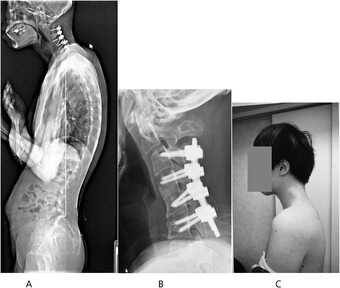

Surgeons carried out an intricate procedure that entailed removing bruised bits of vertebrae and scar tissue, followed by the implantation of metal rods and screws to stabilize and realign the spinal posture. Six months passed before the patient regained the ability to keep his head level.

At one-year follow-up, swallowing problems had cleared up, posture was stable, and quality of life had dramatically improved.

The group concluded that the condition was caused by an "underlying developmental disorder" but that the long-term consequences of prolonged smartphone use with this posture were the biggest contributor to his illness.

What Is Dropped Head Syndrome?

Dropped head syndrome (DHS), also referred to as "floppy head syndrome," is an uncommon disorder that involves, at times severe, weakness of the neck muscles, resulting in a "chin-on-chest" posture.

It is most commonly linked to neuromuscular disorders like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson's disease, or specific muscular dystrophies. The patients tend to use their hands to support their heads and can have difficulties with eating, talking, and walking.

In ALS, DHS happens in approximately 1–3% of the patients and is typically progressive with a grim prognosis. But as this Japanese case suggests, DHS may also arise due to non-neurological etiologies such as trauma, drug abuse, or—as in this instance—chronic mechanical stress of posture.

Can Screen Time Be Associated With Dangerous Conditions?

Although this instance is unusual, physicians caution it shows an expanding medical danger associated with mobile phone addiction. Over 6.8 billion individuals across the globe currently have access to smartphones, with four to seven hours of average screen time per day. Among game players and youth, use can be much higher.

Protracted downward neck posture—a sometimes termed "tech neck"—is already associated with headache, eye strain, and degeneration of the cervical spine. This is the extreme example of DHS and serves to illustrate how serious the effects can be when posture is neglected.

How Does Dropped Head Syndrome Affect Everyday Life?

DHS is more than just an inconvenient posture. The deformity affects simple functions such as swallowing, speaking, and breathing. It inhibits mobility, renders everyday activities challenging, and results in social withdrawal and isolation. In younger individuals, it even generates a chain of physical disability that multiplies mental health issues.

In this patient's life, bullying during childhood and later ostracism provided fertile ground for technological dependence. His case is particular about pointing to the juncture of mental well-being, online tendencies, and bodily well-being—a synergistic combination that is all the more pertinent in contemporary societies.

Organizations like the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons have already warned of increasing incidence of posture-related spinal disorders in young people. The majority will never suffer from DHS, yet milder but chronic neck and back ailments are sweeping up teenagers and young adults.

Elizabeth Jarman from Médecins Sans Frontières, citing parallel access problems with diabetes care, emphasized that the first step to prevention is awareness. In the case of digital health, professionals are calling for schools, workplaces, and families to include posture education and frequent movement as part of daily practice.

Can Dropped Head Syndrome Be Prevented?

Prevention of dropped head syndrome due to posture is easy in principle:

- Avoid repetitive forward flexion of the neck.

- Take frequent breaks from screen time.

- Do neck-strengthening and posture-improving exercises.

- Employ ergonomically arranged seating and screen configurations.

But putting these measures into practice takes awareness and discipline—two qualities usually lacking in the fast-engagement era of mobile gaming and social media.

Is Surgery the Only Option for DHS Treatment?

For cases as bad as the Japanese gamer's, surgery is still the only real option. Surgical procedures are not without hazard, though, from infection to nerve damage. Even if successful, recovery is long and needs rigorous rehabilitation.

Due to the relative infrequency of DHS, there is no gold standard for surgical treatment. Each case has to be assessed on its merits, weighing risks against benefits.

This is an extreme case, but it is one that should serve as a warning to young people everywhere. The frequency of "tech neck" complaints in clinics, alongside rising screen time, indicates there could be more cases of spinal deformities emerging if awareness is not given high priority.

As the Japanese physicians who attended to the gamer stressed, the illness might have been precipitated by the integration of physical posture and pre-existing susceptibilities, but excessive use of smartphones in uncomfortable positions may produce unimaginably tragic results.

Brain’s ‘Clean Sweep’ Could Help You Lower Your Risk Of Dementia

(Credit-Canva)

Our body is like a self-maintaining machine, it is equipped to help us heal ourselves, recharge after a long day’s work as well as having its own warning system to ensure places that need help come to notice, i.e., pain. However, did you know your brain could also actively be stopping you from developing mental health conditions? Yes, your brain and body are not as defenseless as you may think it to be, with the help of sleep, your brain is actively keeping you from developing certain issues.

The brain has a unique way of getting rid of waste, almost like a personal cleanup crew. This process, called the glymphatic system, is thought to work best while we're sleeping. But what happens if our sleep is disrupted?

Researchers believe that a lack of good sleep might stop this system from working correctly, leading to a build-up of waste or toxins in the brain. Some are suggesting this buildup could increase a person's risk of developing dementia.

How the Brain Clears Out Waste

Every cell in your body creates waste, and outside the brain, a system called the lymphatic system takes care of it. But the brain doesn't have these vessels, so how does it stay clean?

About 12 years ago, scientists discovered the glymphatic system. It uses a fluid that surrounds your brain and spinal cord, called cerebrospinal fluid, to "flush out" toxins. This fluid flows through the brain, collects waste, and then drains it away.

Waste products

According to the National Institute of Health one key waste product is a protein called amyloid beta (Aβ). When Aβ builds up, it can form plaques in the brain. These plaques, along with other protein tangles, are a clear sign of Alzheimer's disease, the most common type of dementia.

Sleep and waste

Studies in both humans and mice have shown that Aβ levels increase when you're awake and then drop quickly while you sleep, like the 2018 study published in the Annals of neurology.. This supports the idea that the brain is more actively "cleaning" during sleep.

How Is Sleep Connected To Dementia?

If sleep helps clear toxins, what does long-term disrupted sleep, like that from a sleep disorder, mean for your brain's health?

Sleep Apnea

This common condition causes a person's breathing to stop and start repeatedly during the night. This can lead to a long-term lack of sleep and reduced oxygen, both of which may cause toxins to build up in the brain. Studies have linked sleep apnea to a higher risk of dementia, and some research shows that treating sleep apnea helps clear more Aβ from the brain.

Insomnia

Having trouble falling or staying asleep over a long period has also been linked to an increased risk of dementia. While these links are promising, scientists are not yet sure if treating these sleep problems directly lowers the risk of dementia by removing toxins from the brain.

Does Sleep Aid Brain Health?

Another study, published in the Nature publication 2024, showed that neurons act like miniature pumps. During sleep, these neurons produce rhythmic bursts of electrical energy that create waves. These waves are not just a sign of a sleeping brain; they actually push fluid through brain tissue, effectively washing away waste.

This discovery helps explain why a good night's sleep is so important for brain health. As Dr. Jonathan Kipnis, the senior author, said, "We knew that sleep is a time when the brain initiates a cleaning process to flush out waste and toxins it accumulates during wakefulness. But we didn’t know how that happens."

The researchers believe the brain might adjust its cleaning method based on the type and amount of waste, similar to how we adjust our hand motions when washing dishes—using big, slow movements for large messes and faster, smaller ones for sticky spots.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited