- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Do Dads Experience Postpartum Depression?

Credits: Canva

By now, we all must be aware of how a mother's body changes during and even after pregnancy. What comes next is a challenging phase, called postpartum. However, it is not just the mothers, but dads too go through postpartum depression. As per the UT Southwestern Medical Center, 1 in 10 dads struggle with postpartum depression (PPD) and anxiety. According to a 2019 study published in Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, a peer reviewed journal providing evidence-based information, titled Postpartum Depression in Men by Jonathan R Scarff defines postpartum depression as an episode of major depressive disorder occurring soon after the birth of a child. While it is frequently reported in mothers, but can also occur in father. However, there is no established criteria for this in men, although it could present over the course of a year, with symptoms of irritability restrict emotions, and depression.

Why Do Dads Experience PPD?

Fathers can also experience postpartum depression (PPD) due to various factors, including a history of depression, relationship conflicts, financial stress, and maternal depression. Sleep deprivation and disrupted circadian rhythms, known to affect maternal mental health, may also contribute to PPD in men. Additionally, hormonal changes during and after pregnancy play a role. Studies suggest that lower testosterone levels in new fathers reduce aggression and enhance responsiveness to a baby’s cries, while increased estrogen levels promote more engaged parenting. However, these hormonal shifts can also increase vulnerability to depression. Low testosterone is directly linked to depressive symptoms, and imbalances in estrogen, prolactin, vasopressin, and cortisol may hinder father-infant bonding, further exacerbating PPD symptoms.

In fact the study also goes on to note that fathers can experience prenatal depression like mothers too. While it depends on the kind of environment they are in, here are some of the common reasons why dads feel this way:

Hormonal Changes: As per a 2014 study published in the American Journal of Human Biology, titled Prenatal hormones in first-time expectant parents: Longitudinal changes and within-couple correlations, showed that fathers experience hormonal changes during and after their partner's pregnancy. The main reason is the decline in testosterone.

Feeling Disconnected: While dads also want to be part of the newborn experience, the baby usually spends most of the time with the mother. It may make them feel like they are on the "outside".

Other reasons include the pressure that a father feels. Parenting is not easy, it adds on to financial pressure, and this thought could also lead to depression. Especially, if depression runs in father's family, he is more likely to feel depressed with these changes around him. Most new parents underestimate the role lack of sleep plays in their lives. Staying up all night trying to get your baby to eat or sleep can leave you feeling sleep deprived, which could be one of the reasons why the father too may feel tired and depressed.

What Can Be Done?

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that postpartum depression screenings not be solely the responsibility of obstetrician, and it must be done by pediatricians too to incorporate maternal health. However, fathers too should go for such screenings. In fact, in 2020, an editorial in the Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics called on pediatricians to assess the mental health of all new parents regardless of gender.

The ray of hope here is that more and more people are talking about it and are able to recognize the depression dads also go through. The change is not just for moms, but also for dads, thus it is important that they also are taken care of.

Is This Common Pregnancy Drug Linked To Cancer? Streeting Urges Public Inquiry

Credits: Harm and Evidence Research Collaborative and Association for Women In Science

This common pregnancy drug could be linked to cancer. Wes Streeting has been urged to launch a public inquiry into a miscarriage drug called Diethylstilbestrol, which, reports say has "ruined and devastated" the lives of countless women. On Monday, the Health Secretary Streeting met victims of the pregnancy drugs, which has been linked to cancer, early menopause and infertility.

What Is Diethylstilbestrol?

Diethylstilbestrol, commonly known as DES, is a synthetic form of female hormone estrogen, which was prescribed to thousands of pregnant women from 1940 to 1970s.

The drug was used to prevent miscarriage, premature labor and complications of pregnancy. This was also used to suppress breast milk production, as an emergency contraception and to treat symptoms of menopause.

What Is The DES Controversy?

In 1971, Diethylstilbestrol (DES) was linked to a rare cancer of the cervix and vagina known as clear cell adenocarcinoma, prompting US regulators to advise that it should no longer be prescribed to pregnant women. Despite this, the drug continued to be given to expectant mothers across parts of Europe until 1978. DES has also since been associated with other cancers, including breast, pancreatic and cervical cancers, The Telegraph reported.

Campaign group DES Justice UK (DJUK) is now urging Health Secretary Wes Streeting to order a public inquiry and introduce an NHS screening programme to identify people who may have been exposed to the drug before birth.

Victims described DES as “one of the biggest pharmaceutical scandals this country has ever seen,” warning that “the impact of this terrible drug cannot be underestimated as it has ruined and devastated so many lives,” according to The Telegraph.

In November, Streeting acknowledged that the “state got it wrong” and issued an apology to those affected. He also advised anyone who believes they may have been exposed to DES to speak to their GP.

Susie Martin, 55, from Manchester, whose mother was prescribed DES during pregnancy, told The Telegraph she has undergone between 20 and 30 operations as a result of the drug’s effects.

“The impact of this terrible drug cannot be underestimated as it has ruined and devastated so many lives, including my own,” she said. “The physical and emotional pain has been unbearable. I live with a constant fear that I will need more surgery or develop cancer—and I am far from the only one.”

Calling DES a “silent scandal,” Martin said she hopes the government’s engagement will lead to concrete action. “While I welcome Mr Streeting meeting us, it will only matter if he commits to meaningful steps for victims of this shameful chapter in British medical history, including a screening programme and a full statutory public inquiry,” she added.

What Is Happening With The DES Victims?

The Telegraph reported that compensation schemes have been set up for DES victims in the US and Netherlands, however, UK does not have one yet.

"There are harrowing accounts of harm caused by the historic use of Diethylstilbestrol (DES). Some women and their relatives are still suffering from the associated risks of this medicine which have been passed down a generation, and haven’t been supported. The Secretary of State has been looking seriously at this legacy issue and carefully considering what more the government can do to better support women and their families who have been impacted. NHS England has alerted all cancer alliances to this issue so that healthcare professionals are aware of the impacts of DES and the existing NHS screening guidance which sets out the arrangements for those who show signs and symptoms of exposure,” said a Department of Health and Social Care spokesman to The Telegraph.

COVID Vaccination Is Not Linked To Reduce In Childbirth, Says Study

Credits: iStock and Canva

A large population-based study from Linköping University in Sweden has found no evidence that COVID-19 vaccination caused a decline in childbirth during the pandemic, countering persistent rumors that mRNA vaccines affect fertility. The findings have been published in the peer-reviewed journal Communications Medicine.

The study was conducted amid widespread misinformation, particularly on social media, suggesting that COVID-19 vaccines reduce the chances of becoming pregnant. These claims gained traction as several countries, including Sweden, recorded a drop in birth rates during the later stages of the pandemic, prompting questions about a possible link to vaccination.

“Our conclusion is that it’s highly unlikely that the mRNA vaccine against COVID-19 was behind the decrease in childbirth during the pandemic,” said Toomas Timpka, professor of social medicine at Linköping University and one of the study’s authors.

Why Researchers Investigated the Claim

Since the early months of the pandemic, unverified claims about vaccines and fertility have circulated widely online. When official data later showed fewer babies being born in some regions, researchers decided to examine whether vaccination could plausibly explain the trend or whether other social and demographic factors were at play.

Read: Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy, Showed X-Ray, Doctors Remove It Via Endoscopy

To address the issue, the research team carried out an extensive analysis using real-world healthcare data rather than surveys or self-reported outcomes.

Study Looks at Nearly 60,000 Women

The study analyzed health records of all women aged 18 to 45 years living in Region Jönköping County, a region with a total population of around 369,000 people. This amounted to nearly 60,000 women included in the analysis.

Between 2021 and 2024, about 75 per cent of these women received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Researchers examined data on childbirths, registered miscarriages, vaccination status and deaths using official healthcare records, allowing for a comprehensive comparison between vaccinated and unvaccinated groups.

Importantly, the researchers adjusted their analysis for age, recognizing that age is one of the most significant factors influencing fertility and pregnancy outcomes.

No Difference in Births or Miscarriages

When childbirth rates were compared between vaccinated and unvaccinated women, the researchers found no statistically significant difference. The same held true for miscarriage rates among women who became pregnant during the study period.

“We see no difference in childbirth rates between those who have taken the vaccine and those who haven’t,” said Timpka. “We’ve also looked at all registered miscarriages among those who became pregnant, and we see no difference between the groups there either.”

These findings align with several earlier international studies that have similarly found no association between COVID-19 vaccination and reduced fertility.

Other Factors Likely Behind Falling Birth Rates

According to the researchers, the decline in childbirth observed during the pandemic is more plausibly explained by broader demographic and social trends.

People currently in their 30s, the age group most likely to have children, were born in the second half of the 1990s. That period was marked by economic challenges and lower birth rates in Sweden, meaning today’s pool of potential parents is smaller than in previous generations.

In addition, pandemic-related factors such as health concerns, economic uncertainty, delayed family planning and lifestyle changes during lockdowns may have contributed to fewer pregnancies.

One of the study’s key strengths is its large, representative sample drawn from an entire region rather than a selected group. By using verified healthcare records and accounting for age-related effects, the researchers aimed to minimize bias and improve reliability.

The study received financial support from several sources, including the Swedish Research Council.

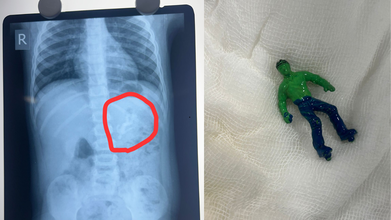

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy, Showed X-Ray, Doctors Remove It Via Endoscopy

Credits: X

Ahmedabad toddler, one-and-a-half-year-old boy swallowed a 'Hulk' toy, which is based on a popular comic superhero. The toy was stuck in his stomach when his parents took him to the Civil Hospital. According to reports by News18, the child is identified as Vansh who showed the signs of discomfort and began vomiting. This is what alarmed the parents.

As per the News18 report, his mother Bhavika was suspicious when she noticed that one of his toys was missing. The child was rushed to the hospital and an X-ray revealed that he had swallowed the entire plastic toy. The toy was not broken.

Hindustan Times reported that Dr Rakesh Joshi, Head of the Department of Pediatric Surgery removed the toy through upper GI endoscopy. "Had it been a little late, the toy could have moved further from the stomach and got stuck in the intestines. In that case, there would have been a risk of intestinal blockage and even rupture," the senior doctor said.

"There is a natural valve between the esophagus and the stomach. The biggest challenge was to take out a whole toy through this valve. When we tried to grab it with the endoscope, the toy kept slipping because of the air in the stomach. Pulling the toy by its hand or foot raised the possibility of it getting stuck in the valve and causing it permanent damage," he said.

The doctor noted that if the toy had further slipped down, it would have increased the risk of intestine rupturing.

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy: What Parents Must Keep In Their Mind

Under the Toys (Quality Control) Order, 2020 issued by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, toy safety in India was brought under mandatory BIS certification from September 1, 2020. The move aims to ensure safer toys for children while also supporting the government’s policy of curbing non-essential imports.

Industry sources estimate that more than 85 percent of toys sold in India are imported. Officials say the Toys Quality Control Order is a key step in preventing the entry of cheap and substandard toys into the domestic market, many of which fail to meet basic safety requirements.

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy: Standards for Electric and Non-Electric Toys

The quality control order clearly defines safety standards based on the type of toy. Non-electric toys such as dolls, rattles, puzzles, and board games must comply with IS 9873 (Part 1):2019. These toys do not rely on electricity for any of their functions.

Electric toys, which include at least one function powered by electricity, are required to meet the standards outlined under IS 15644:2006. Compliance with these standards is mandatory before such toys can be sold in the Indian market.

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy: Risks Linked to Untested Toys

Toys that are not tested by NABL-accredited toy testing laboratories can pose serious health risks to children. Sharp edges and poorly finished parts can cause cuts and injuries. PVC toys may contain phthalates, which are considered harmful chemicals.

Many low-quality toys have also been found to contain lead, a substance known to be particularly damaging to brain development in children. Soft toys with fur or hair can trigger allergies or become choking hazards. In some cases, small body parts can get stuck in gaps or holes, increasing the risk of injury.

Testing by NABL-accredited laboratories ensures that toys are safe, durable, and suitable for specific age groups. Parents are advised to check for IS marks on toys before purchasing, as this indicates compliance with Indian safety standards.

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy: What Parents Should Check Before Buying Toys

Experts recommend avoiding toys with small detachable parts for toddlers and young children, as they are more likely to put objects in their mouths. Toys should always match the child’s age, skill level, and interests.

Parents are also urged to look for IS marks, which confirm that the toy has been tested and certified. Loud toys should be avoided, as prolonged exposure to sounds above 85 decibels can harm a child’s hearing.

Electric toys with heating elements should be used with caution or avoided altogether due to burn risks. Finally, toys with sharp edges or shooting components should be carefully examined to prevent cuts and injuries.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited