- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Breakthrough In Cancer Treatment: New Vaccine Shows Tumour Stabilization In Advanced Cases

Cancer vaccination (Credit: Canva)

A new vaccine designed to fight cancer cells is showing promising signs in early-stage clinical trials, offering fresh hope for people with advanced cancers. The groundbreaking treatment, developed by Moderna—the pharmaceutical company behind one of the leading COVID-19 vaccines—could represent a significant step forward in cancer treatment.

The vaccine, known as mRNA-4359, is designed to prime the immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells, much like how COVID-19 vaccines teach the body to identify and fight the virus. By using mRNA technology, it instructs the body’s immune system to differentiate between healthy and cancerous cells, triggering a targeted immune response to fight tumours.

How does the Vaccine work?

In the initial phase-one clinical trial, 19 patients with advanced solid tumours, such as melanoma and lung cancer, were administered the mRNA-4359 vaccine. Of the 16 patients evaluated, eight showed no tumour growth or development of new tumours, a promising outcome considering their advanced conditions. The treatment was also well-tolerated, with no severe side effects reported, marking an encouraging milestone in cancer immunotherapy.

Chief investigator Dr. Debashis Sarker from King’s College London noted that the trial, while still in early stages, demonstrated the vaccine’s ability to safely stimulate the immune system. “This study evaluating an mRNA cancer immunotherapy is an important first step in hopefully developing a new treatment for patients with advanced cancers,” Dr. Sarker said. However, he stressed the need for further research due to the small sample size involved in the trial.

What Makes This Vaccine Different?

The cancer vaccine uses similar technology to that employed in Moderna's COVID-19 vaccines. It works by mobilizing the immune system to recognize cancer-specific proteins, prompting a more precise attack on tumour cells. What makes this approach unique is its potential to target various cancers, particularly in patients whose cancers are resistant to conventional therapies.

Currently, the vaccine is being tested in combination with pembrolizumab (Keytruda), an immunotherapy drug commonly used in chemotherapy, in patients with melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer. The aim is to assess whether the combined treatment can create a more favourable tumour environment for the immune system to attack cancer cells.

What Does This Mean for Cancer Patients?

While the results are promising, experts caution that the vaccine is still in the early stages of development. Dr. Sarker emphasized that it’s too soon to determine its overall effectiveness. However, the encouraging results offer a ray of hope for people with advanced-stage cancers, who often have limited treatment options.

This trial is just one of several exploring the use of mRNA vaccines to treat cancer. Another promising trial involves a personalized mRNA vaccine for melanoma, mRNA-4157, which uses DNA sequencing and artificial intelligence to create a tailored vaccine for each patient’s tumour. Additionally, BioNTech, the German company behind another COVID-19 vaccine, is testing a lung cancer vaccine (BNT116) in patients in the UK and beyond.

Given the rising number of cancer cases worldwide—over 48,000 people are diagnosed with lung cancer in the UK each year, with 35,000 deaths—it’s clear that more effective treatment options are urgently needed. Could cancer vaccines like mRNA-4359 hold the key?

Moderna’s trial is now enrolling more patients across the UK, USA, Spain, and Australia, as researchers continue to study the vaccine’s effectiveness. As mRNA technology continues to advance, the potential for a cancer vaccine that could offer long-term protection and treatment for various types of cancer grows increasingly within reach.

Could cancer vaccines be the future of cancer treatment? What hurdles remain before these treatments can become widely available? While there are still many questions, the early results from these trials signal a shift in how we approach cancer therapy, offering a new frontier of hope for patients and their families.

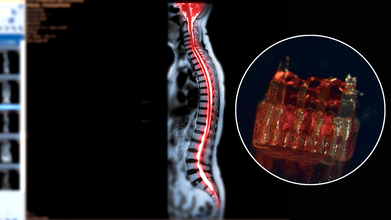

Tiny 3D-Printed Spinal Cords Could Reverse Paralysis, How Did Scientists Make It Work?

Credits: Canva/McAlpine Research Group, University of Minnesota

Spinal cord injuries have long posed one of the most stubborn challenges in medicine. Affecting more than 300,000 people in the United States alone, these injuries often lead to permanent paralysis because damaged nerve fibers fail to regenerate across the site of trauma. Traditional therapies focus largely on rehabilitation and symptom management rather than reversing the underlying injury. Now, a groundbreaking study from the University of Minnesota Twin Cities suggests that a combination of 3D printing, stem cells, and lab-grown tissues could change that narrative. Researchers have engineered tiny scaffolds that guide stem cells to form nerve fibers capable of bridging severed spinal cords. In rat models, this approach restored nerve connections and movement—offering a tantalizing glimpse into the future of paralysis treatment.

At the heart of this innovation are organoid scaffolds—microscopic 3D-printed structures designed to direct stem cell growth. These scaffolds contain a network of tiny channels that can be seeded with spinal neural progenitor cells (sNPCs). Originating from human adult stem cells, sNPCs have the potential to differentiate into the various types of neurons needed for spinal cord repair. The scaffold essentially provides a framework for these cells, ensuring they grow along the correct pathways to reconnect disrupted nerve circuits.

Guebum Han, a former postdoctoral researcher in mechanical engineering at the University of Minnesota and the study’s first author, explains, “We use the 3D printed channels of the scaffold to direct the growth of the stem cells, which ensures the new nerve fibers grow in the desired way. This method creates a relay system that, when placed in the spinal cord, bypasses the damaged area.”

To test their approach, the researchers transplanted the scaffolds into rats with completely severed spinal cords. Over time, the stem cells differentiated into mature neurons and extended their nerve fibers in both directions—toward the head (rostral) and toward the tail (caudal)—forming new connections with the host’s existing spinal circuitry.

The results were remarkable. Rats that received the organoid scaffolds showed significant functional recovery compared to controls, regaining movements that were previously impossible. The new neurons integrated seamlessly into the host tissue, demonstrating that lab-grown spinal tissue could not only survive transplantation but also restore communication across previously severed areas.

Can Lab-Grown Organs Help Patients?

While the research is still in its early stages, the potential implications for human medicine are profound. Spinal cord injuries have been notoriously resistant to treatment because adult nerve cells rarely regrow once damaged. This study provides proof-of-concept that targeted, scaffold-guided stem cell growth can rebuild the neural network necessary for motor function.

Ann Parr, professor of neurosurgery at the University of Minnesota, emphasizes the significance: “Regenerative medicine has brought about a new era in spinal cord injury research. Our laboratory is excited to explore the future potential of our ‘mini spinal cords’ for clinical translation.” The team hopes to refine the technique, scale up scaffold production, and move toward clinical trials that could one day benefit people living with paralysis.

Despite the promising results, several hurdles remain before this technology can be applied to humans. Scaling the tiny lab-grown spinal cords to the size necessary for human injuries will require sophisticated bioengineering solutions. Immune rejection and integration into a complex, pre-existing nervous system present additional challenges. Moreover, safety and efficacy will need to be rigorously tested in larger animal models before human trials can proceed.

The ethical considerations of stem cell use and genetic manipulation also require careful navigation. While adult stem cells used in this study bypass some of the ethical debates associated with embryonic stem cells, clinical applications must still adhere to stringent regulatory standards.

The merging of 3D printing, stem cell science, and lab-grown tissue engineering represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine. The concept of “mini spinal cords” could open the door to therapies not only for spinal cord injuries but potentially for other neurodegenerative diseases that involve nerve degeneration, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or multiple sclerosis.

Moreover, these technologies exemplify the broader trend of personalized medicine. By tailoring organoid scaffolds to individual patients, it may become possible to repair nervous system injuries with unprecedented precision. This could drastically improve outcomes, reduce rehabilitation times, and enhance quality of life for patients who currently have few options.

The University of Minnesota study is an early but significant step toward reversing paralysis. By combining 3D-printed scaffolds, stem cell biology, and lab-grown spinal tissue, researchers have demonstrated that damaged neural pathways can be rebuilt and functional recovery is achievable—at least in animal models.

While human applications are still a way off, the research provides a blueprint for the future of spinal cord repair and regenerative neuroscience. For the millions affected by spinal cord injuries, these tiny lab-grown spinal cords could one day offer more than hope—they could offer a pathway to regained movement and independence.

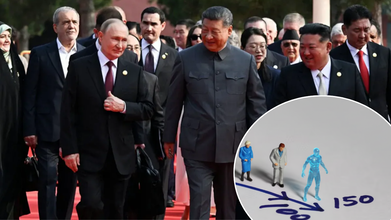

Hot Mic Moment: What Putin, Xi Said About 'Living Indefinitely'; Can Humans Really Live For 150-Years?

Credits: Reuters/Shutterstock/AI

At a military parade in Beijing, an open-mic moment between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin revealed an unusual exchange. The leaders were overheard discussing organ transplants and the possibility of dramatically extending human life. Putin even raised the prospect of “eternal life” through biotechnology, according to translated remarks aired on Chinese state TV. The conversation, captured as Xi, Putin, and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un walked through Tiananmen Square, has fueled fresh debate on the limits of science and longevity. Both Xi and Putin, in power for 13 and 25 years respectively, have shown no signs of stepping down.

The pageantry was meant to project strength, but a stray hot mic gave the world something unexpected: an intimate glimpse into how two of the most powerful men on Earth think about the human lifespan.

Putin’s interpreter was caught saying, “Biotechnology is continuously developing. Human organs can be continuously transplanted. The longer you live, the younger you become, and even achieve immortality.” Xi responded, almost casually: “Some predict that in this century humans may live to 150 years old.”

The microphones were quickly faded out, and the livestream camera cut away. But the brief exchange rippled far beyond the parade. Could 150 really be the ceiling for human life—or even a realistic milestone?

What is The Hot Mic Moment?

Both Xi and Putin later confirmed the conversation, with Putin remarking to Russian media that new medical advances, including organ replacement, could extend “active life” significantly. For leaders who have each been in power for more than a decade—and show no signs of stepping aside—the notion of extending life carries not just personal but political undertones.

This wasn’t idle speculation in a vacuum. Russia, China, and the United States are all investing heavily in biotechnology, regenerative medicine, and artificial intelligence as tools not only of economic growth but also of national prestige. Against that backdrop, Xi’s mention of 150 years sounded less like science fiction and more like a pointed acknowledgment of what researchers are seriously debating.

How Long Do Humans Live Now?

At present, global life expectancy hovers around 73 years, with wealthier countries averaging in the low 80s. The record for the oldest documented human belongs to Jeanne Calment, a Frenchwoman who lived to 122 before passing in 1997.

But it’s important to separate two concepts: average life expectancy (how long most people live, heavily influenced by disease, healthcare access, and environment) and maximum lifespan (the theoretical upper limit of human survival under ideal conditions). Average life expectancy has steadily climbed over the past century thanks to vaccines, antibiotics, improved sanitation, and better maternal care. Maximum lifespan, by contrast, has barely budged.

That’s why Xi’s remark matters. He wasn’t talking about incremental gains—he was floating the possibility of breaking through a biological barrier.

Can Humans Live As Long As 150 Years?

A team of scientists from Singapore, Russia, and the United States recently modeled human resilience using blood samples from more than 70,000 people aged up to 85. They tracked fluctuations in white and red blood cells to create a measure called the Dynamic Organism State Indicator (Dosi), which captures the body’s ability to recover from stress and illness.

Their conclusion was striking: resilience collapses completely around age 150, setting an upper bound for human lifespan. This wasn’t a forecast of what people will achieve anytime soon—it was a theoretical ceiling based on current biology.

Put simply, the study suggests that even if you dodge heart disease, cancer, infections, and accidents, your body will eventually lose its ability to recover. That’s the point at which life becomes unsustainable.

Is Living Till 150 Years Plausible Or Out of Reach?

From a biological standpoint, the 150-year limit makes sense. Organs age, stem cells lose regenerative capacity, and the body accumulates damage at the cellular level. At present, most human organs seem capable of functioning for 110 to 120 years under ideal conditions. Beyond that, decline accelerates.

Yet science is moving fast. Regenerative medicine, organ transplantation, and lab-grown tissues could shift the baseline. Already, researchers have extended the lives of worms tenfold and mice by 30–40%. Humans, with more complex biology, are harder to push, but the trajectory suggests improvement is possible.

Still, adding 25–30 years of healthy life is far more realistic in the near future than reaching 150. As one researcher quipped, “We might not see immortality, but 110 could become the new 90.”

Evidence from real-world populations supports the idea that genetics and lifestyle can push lifespans well beyond the norm. The “Blue Zones”—regions like Okinawa in Japan and Sardinia in Italy—produce unusually high numbers of centenarians. Their secrets aren’t futuristic: plant-heavy diets, daily movement, strong community ties, and low chronic stress.

Even so, these populations rarely see people surpassing 110. Jeanne Calment remains an outlier, not a model. Which raises the question: are biology and environment already giving us the maximum return, or is medicine the only path to break through?

What Role Does Biotechnology Play?

This is where Putin’s remark about organ transplants comes in. Medicine has already normalized replacing failing hearts, kidneys, and joints. Stem cell therapies are being tested to repair damaged tissues. Artificial intelligence is accelerating drug discovery. CRISPR and gene editing open the possibility of correcting mutations that drive aging and disease.

Theoretically, if each organ could be replaced or rejuvenated before it fails, the body could remain younger for longer. The challenge is that aging is systemic. Replacing a heart doesn’t stop immune decline, nor does repairing a kidney fix memory loss. The body doesn’t age in silos; it ages all at once.

How Can Political Leaders Shape The Theory of Longevity?

It’s no accident that authoritarian leaders are voicing interest in radical life extension. Both Xi and Putin oversee nations that pour resources into biotechnologies, often with fewer ethical guardrails than in the West. Extending human lifespan is not just a health goal—it’s a geopolitical lever, a way to showcase scientific dominance.

At the same time, public health experts caution against letting these conversations distract from pressing needs. In countries where average life expectancy still lags below 70, access to vaccines, clean water, and chronic disease care would do far more for human survival than speculative anti-aging research.

For now, the 150-year limit is a provocative talking point, not a practical horizon. But Xi and Putin’s hot mic exchange underscores something deeper: longevity science has moved from the fringes to the geopolitical stage.

If history is any guide, the biggest gains won’t come from science fiction-style immortality but from steady, incremental progress—cutting smoking rates, controlling hypertension, managing diabetes, and ensuring equitable access to healthcare. These measures, not transplants or futuristic drugs, are what extend average life expectancy year after year.

The mic may have been unguarded, but the conversation it captured was anything but trivial. Leaders of two nuclear powers spoke openly about the possibility of living indefinitely. While the science points to 150 years as a theoretical ceiling, the more pressing challenge for humanity is not how long we can live, but how well.

As researchers continue probing the biology of aging, the lesson from Blue Zones and centenarians alike still rings true, a balanced diet, physical activity, meaningful social ties, and preventive healthcare remain the closest things we have to longevity secrets. The road to 150 may or may not be real, but the path to 100—healthy, independent, and vibrant—is already within reach.

Over Six Years, Life Expectancy In India Rises By 0.5 Years While Women Outlive Men By Almost Four Years

Credits: iStock

India has seen a gradual overall improvement in life expectancy at birth over recent years, reflecting advances in healthcare, nutrition, and disease management. According to the latest official data, life expectancy at birth for the period 2019–23 is estimated at 70.3 years, up from 69.8 years in 2017–21. Even the 2018–22 period reported a slight rise to 69.9 years, indicating a consistent, if incremental, upward trend.

This gain is more than a figure; it is an indicator of a nation slowly emerging from past issues of infectious diseases, child and maternal mortality, and a lack of healthcare access in rural communities. However, despite the portrait of improvement painted by the national rate, a closer examination of the data shows regional and gender variations that are worth noting.

Are Women Outliving Men Now?

Perhaps the most remarkable characteristic of India's life expectancy statistics is the persistent disparity between women and men. In all three reporting periods, women not only survive longer at birth but also have a longevity advantage even at older ages.

In 2017–21, female life expectancy at birth was 71.6 years, compared to 68.2 years for men. By 2018–22, females reached 71.9 years, with males at 68.2 years. The 2019–23 data shows a more pronounced gap: females at 72.5 years, males at 68.5 years—nearly a four-year difference at birth.

Even at 70 years of age, women still have a survival advantage of over one year over men. This continuing disparity highlights biological, social, and behavioral mechanisms that are more conducive to women's survival. Women are less likely to be exposed to lifestyle risk factors like smoking and heavy drinking, and investigations also identify protective hormonal effects and more robust immune reactions as being causative.

The broadening gap also mirrors gains in the health of mothers, disease avoidance, and medical care coverage for women in India. As women keep surviving longer than men, public health efforts need to evolve in response to their needs in terms of, among others, the care of the elderly, chronic disease care, and social support networks.

Urban-Rural and State-Level Disparities

The gains in life expectancy are not even across India. Recent data underscore significant regional disparities:

Chhattisgarh has the lowest life expectancy consistently: males 62.4–62.8 years, females 66.4–67.1 years.

Delhi and Kerala continue to lead, with females achieving 78.4 years in Kerala and males 73.0 years in Delhi.

Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Kerala also show high male and female life expectancy compared to the national average.

Urban-rural differentials continue but have weakened considerably over the decades. For example:

During 2017–21, urban populations averaged 72.9 years, rural populations 68.5 years—a 4.4-year disparity.

By 2019–23, the disparity decreased slightly: urban life expectancy at 73.1 years, rural at 69.1 years, a 4-year difference.

At the age of 70, urban-rural disparities are narrower, averaging 1.5–1.9 years, an indication of increased rural healthcare and preventive services access.

Even with the decrease in the gap, rural communities still lag behind in terms of lesser access to quality care, greater infectious disease prevalence, and lesser awareness of preventive health practices. The disparities underscore the requirement for policies directed towards bridging the urban-rural divide.

Life Expectancy After Birth: Trends by Age

Life expectancy is more than a birth rate; it also reflects survival chances at various ages. The data reveal:

Life expectancy at age one (having survived infancy) has risen steadily: males from 69.5 years (2017–21) to 69.5 years (2019–23), females from 73.1 years to 73.6 years.

Life expectancy at age 60 is 18.4 years across the country (17.3 years for males, 19.6 years for females), so Indian adults can realistically hope to live well into their late 70s and early 80s if they survive to older age stages.

These age-specific trends mirror the effect of reduced infant mortality, enhanced disease control, and enhanced nutrition and sanitation. They also demonstrate women's resilience in living longer than men even at later ages, furthering the gendered character of longevity benefits.

Public Health Implications

The life expectancy trends throw up the imperative implications for India's social and healthcare planning. With women living longer than men and the population fast ageing, increasing needs of geriatric health care services, chronic diseases care, and social support systems are emerging exponentially. States like Chhattisgarh, with low performance, require special intervention to redress regional gaps in terms of maternal and child health, sanitation, and rural health infrastructure.

The female longevity edge also necessitates gender-appropriate measures that focus on preventive care, mental health interventions, and supportive care to provide a quality life for older women. Rural populations, even though they are gradually improving, continue to be prone to avoidable disease, and therefore, there is a need to consolidate healthcare access, encourage preventive testing, and spread health education in villages and small towns.

What Factors Are Driving the Improvements?

A number of factors have led to the steady increase in India's life expectancy:

Increased access to healthcare: Government initiatives such as Ayushman Bharat and state-level health programs have enhanced coverage, particularly for maternal and child health.

Vaccination: Declines in infectious diseases like measles, polio, and diphtheria have helped bring down mortality among children.

Better nutrition and sanitation: Increased dietary awareness and provision of clean water have improved health outcomes overall.

Lifestyle transitions and awareness: Better awareness of smoking cessation, physical activity, and management of chronic conditions has affected survival among adults.

Nonetheless, there are challenges. Chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease are on the increase, jeopardizing future increases in life expectancy. Managing these chronic health costs is necessary to maintain and augment longevity.

What Women's Longevity Advantage Means for The Society?

The reality that women currently live for almost four years longer than men at birth and well over one year even up to age 70 has profound implications in society:

- Healthcare systems have to be modified to provide for increasingly larger numbers of older women who might outnumber old men.

- Economic planning needs to factor in increased retirement lengths and possible dependency ratios, particularly for widows or sole living women.

- Preventive health attention must address age-related conditions for women, such as osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and dementia.

Women's longer life expectancy is a success indicator of general health enhancement, but it also demands gender-sensitive health planning to guarantee women not only live longer but have quality and independence in old age.

India's trends in life expectancy reveal a story of slow and steady progress, powered by expansion of healthcare, control of diseases, and social development. However, the continued existence of regional inequalities, urban-rural differentials, and gendered health disparities ensures that policy focus needs to remain laser-sharp. Strategies in the future must consist of:

- Scaling up preventive care in rural and low-performing states

- Gender-sensitive healthcare service promotion

- Intensifying chronic disease control programs

- Age-specific life expectancy trend monitoring to detect emerging health threats

By targeting these priorities, India can continue to raise life expectancy, narrow inequalities, and make sure men and women do not just live longer but also healthier and more productive lives.

The most recent Indian life expectancy figures show encouraging improvements and remaining disparities. Women still outlive men by a significant margin, a pattern that holds both in urban and rural areas, with regional gaps continuing to be a serious problem. The incremental increase in life expectancy at birth is encouraging, but the path to universal coverage, equitable, high-quality healthcare continues to be a long way off.

As India makes its way through the next decade of public health priorities, attention needs to be given to maintaining these gains, meeting the needs of older persons especially women and closing disparities that push behind rural and performing states. Only then can India unlock the full potential of longer, healthier lives for its people.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited