- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Jenny Mollen Ends Up In ER After Microdosing GLP1 Medication

Credits: Instagram and Canva

US TV Star, the 46-year-old Jenny Mollen was rushed to the Emergency Room due to a reaction that happened after she consumed the weight-loss drug, GLP1 or the glucagon-like peptide-1 medication.

In an Instagram story on June 26, she wrote, “I just posted a follow-up to my piece about Tirzepatide and microdosing. I had a lot of unanswered questions about it [that] just ironically got answered for me in the form of a trip to the ER two nights ago … I’m in such a f***ing haze. It’s been a crazy 48 hours.”

She also revealed that she lost one-fourth of her blood as she ended up in the hospital.

What Is Tirzepatide?

Before we understand what is tirzepatide, it is important to understand how GLP1 medications work. It is a hormone naturally produced in the body that plays a role in regulating blood sugar levels and appetite. GLP-1 receptor agonists are a class of medications that mimic the effects of this hormone, used to treat type 2 diabetes and, increasingly, for weight management.

Tirzepatide, on the other hand is a GLP1, like Ozempic or Wegovy. It regulates a person's blood sugar, appetite, and digestion. These medications are usually used to treat type 2 diabetes and obesity.

What Happened To Mollen?

Mollen, who is the wife of Jason Biggs, also wrote an essay, published on Substack, where she expressed her "growing concerns" about how the medication was affecting her “mentally.”

In her essay, she wrote: “I do think that in the coming years, we will hear more about how GLP1s cause depression, ruin marriages and rob us of our capacity for feeling joy. These drugs bind to our neurotransmitters, affecting levels of dopamine and serotonin. They change our relationship with food. And I believe they also change our relationship with people and ourselves.”

She also noted that why others may have a desire to use it, however, she expressed her concerns over how it could have a negative impact on individual’s mental health, as she also has her own first-hand experience.

She further noted: “When I started Tirzepatide, the first thing I noticed was that I was crying more frequently. I couldn’t control the tears that would pour out of me when talking about subjects ranging from kids to open-faced tuna melts. I also noticed this underlying anxiety that would, without warning, after no more than one cup of espresso, take over my body and have me pacing in the kitchen like I’d just snorted an eightball of cocaine.”

She also noted that she would get irritated much quickly and she was “more easily offended and quicker to react” while she was on GLP1.

She wrote: “I also began to sense that the joy and gratitude I once experienced, those moments of peak happiness, weren’t quite as intense as they used to be. I could feel the joy simmering beneath the surface, but it never reached the pinnacle it once had internally. Even on a rollercoaster, my sense of euphoria was dampened. I couldn’t feel the highs and lows. Satisfaction, personally and professionally, was just out of reach.”

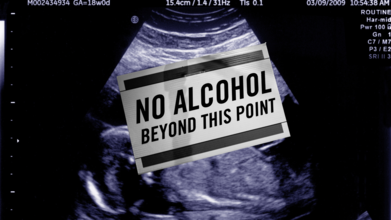

International Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Day 2025: Themes, Significance And History

Credits: Canva

September is globally recognized as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Awareness Month, with September 9 dedicated to International FASD Awareness Day. This year, 2025, carries the powerful theme “Everyone Plays a Part: Take Action!”, a reminder that preventing FASD and supporting those affected is a collective responsibility.

What is FASD and Why It Matters

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) describes the lifelong effects on the brain and body of a baby exposed to alcohol during pregnancy. It can lead to physical, behavioral, and cognitive challenges that persist throughout life. The most severe form, fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), is characterized by distinct facial features, slow growth, learning difficulties, and developmental delays.

FASD Theme 2025

This year’s theme, “Everyone Plays a Part: Take Action!”, is a call to collective responsibility. It highlights that FASD prevention is not just about individual choices but also about community support, healthcare education, and creating safe environments for expectant mothers.

Health professionals are encouraged to screen for alcohol use early in pregnancy, families are urged to provide support to those struggling with alcohol dependence, and policymakers are called upon to ensure inclusive systems for people with FASD. The message is simple yet powerful: prevention and support require all of us.

Experts emphasize that there is no known safe amount of alcohol to consume during pregnancy. Alcohol passes through the placenta to the developing baby, where it can cause permanent brain damage and affect organ development.

Also Read: What Role Do Genes Play In Alcoholism?

Symptoms vary, some children may face intellectual disabilities, behavioral issues, or difficulty with learning and social interaction. Others may experience challenges with coordination, speech, and growth.

The disorder is entirely preventable by avoiding alcohol during pregnancy. However, for those already living with FASD, early diagnosis and intervention can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life.

How FASD Awareness Day Began

International FASD Awareness Day was first observed on September 9, 1999, thanks to the efforts of parents and advocates like Bonnie Buxton, Brian Philcox, and Teresa Kellerman. They chose 9/9/99 to symbolize the nine months of pregnancy, a clear reminder that avoiding alcohol throughout those months can prevent FASD entirely.

What started as a grassroots effort in Canada and the United States has grown into a global movement. Communities worldwide now hold events, educational workshops, and social media campaigns each September to raise awareness, combat stigma, and advocate for better support systems.

Why This Day Matters

FASD Awareness Day is more than an observance, it is a global reminder that thousands of children are still born each year with preventable conditions linked to alcohol exposure. Beyond prevention, the day pushes for better understanding and empathy toward individuals already living with FASD. Stigma often keeps families from seeking help, and awareness campaigns aim to break that silence.

As the world observes FASD Day 2025, the message is clear: by spreading awareness, encouraging alcohol-free pregnancies, and supporting those affected, society can take a step closer to ending preventable harm and building inclusive communities where individuals with FASD can thrive.

Kissing Bugs Disease Could Soon Become An Endemic, Says CDC

Credits: Texas A&M University

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report could be declaring the kissing bug disease or the Chagas disease an endemic in the United States.

But, before we jump into the report, let us understand the difference between an outbreak, endemic, epidemic, and pandemic.

Outbreak: As per the National Collaborating Centers for Infectious Disease, Canada, an outbreak is limited to a specific area, for instance a school, a department store, etc. and it is within a certain time period.

Endemic: The CDC notes that the amount of a particular disease that is usually present in a community is called an endemic. It is also called a baseline. The National Collaborating Centers for Infectious Disease says that an endemic is when it is always present in a geographical area or a population group.

Epidemic: The CDC notes that an outbreak becomes are epidemic when there is a sudden increase in the number of cases of a disease above what is normally expected in that population in a specific area. It can also spread to a larger area, for instance, within the country.

Pandemic: The CDC notes that when an epidemic spreads over several countries and continents, affecting many people, it is called a pandemic.

What Does The CDC Report Say?

In a report published last month in the September issue of the CDC’s Emerging Infectious Diseases journal, researchers highlighted that the disease is already considered endemic in 21 countries across the Americas. They also emphasized that growing evidence of the parasite’s presence in the United States is beginning to challenge the long-standing classification of the country as “non-endemic.”

The report stated that autochthonous, meaning locally acquired, human cases have been confirmed in eight U.S. states, with Texas reporting the highest number of cases. “Labeling the United States as non-Chagas disease-endemic perpetuates low awareness and underreporting,” the authors warned, further pointing out that the insect responsible for transmitting the disease has been detected in 32 states.

In addition to Texas, the other states where human cases have been identified include California, Arizona, Tennessee, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

The report points out that available data is still “inadequate” to conclusively demonstrate whether the insects are expanding in either their geographic range or overall numbers. However, it also highlights that these bugs are being “increasingly recognized,” largely because of their frequent encounters with humans and the growing focus of scientific research.

“Invasion into homes, human bites, subsequent allergic reactions or exposure to T. cruzi parasites, and the rising number of canine diagnoses have all contributed to greater public awareness,” the report stated.

Read: What You Need To Know About Chagas Disease, Is it Contagious?

What Is The Kissing Bug Disease or The Chagas Disease?

Chagas disease is caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, a parasite transmitted by triatomine insects, commonly known as “kissing bugs.” These insects get their nickname because they often bite people on the face, especially while they are sleeping.

Globally, around 8 million people are estimated to be living with Chagas disease, and about 280,000 cases are believed to exist in the United States, many of them undiagnosed.

Transmission occurs when the bug bites and then leaves parasite-containing droppings near the bite site. If a person accidentally rubs or scratches the area, or if the droppings come into contact with the eyes, mouth, or a cut in the skin, the parasite can enter the body and cause infection.

Could A Daily Pill Restore Brain Function After Stroke? Scientists Test Bold New Treatment

Credits: iStock/Canva

Stroke remains one of the leading causes of disability worldwide, often leaving survivors with long-term challenges in movement, memory, and speech. Traditional rehabilitation can alleviate symptoms, but progress is slow and limited for most patients. Researchers are now investigating a game-changer, a pill that could stimulate the brain to regenerate itself. Early studies indicate that approved drugs for other diseases can be repurposed to stimulate sleeping repair processes, providing a new avenue for recovery that previously was not possible. Successful use of this method could reframe the way physicians treat stroke victims and transform the future of neurorehabilitation.

For years, doctors and scientists knew that if damaged, the brain had little to no regeneration capacity. Stroke victims and head injury patients were too often doomed to a lifetime struggle with dysfunctional movement, memory loss, or difficulty speaking. Today, new research contradicts the long-standing principle. A pill in development may activate the brain's ability to heal itself, giving hope to millions of people around the globe.

Strokes, which happen as a result of interrupted blood flow to areas of the brain, continue to be among the major causes of long-term disability. Brain cells are killed through the resulting damage, and survivors are left with physical and mental difficulties that are notoriously hard to reverse. Conventional rehabilitation involves physical therapy and changes in lifestyle, but gains are slow and partial.

"Previously, the medical community believed that adult brains were incapable of producing new neurons after severe damage," describe neurologists who are knowledgeable about the study. "This pill contradicts that by stimulating directly involved pathways to neurogenesis."

The treatment, which comes from adapting already proven drugs like Maraviroc—already approved for other diseases—is aimed at molecular mechanisms thought to induce the birth of new brain cells and fix faulty circuits. If successful, it may significantly lower reliance on resource-intensive rehab programs.

How Does The Stroke Recovery Pill Work?

At the core of this innovation is the capability to "turn on" latent genes that stimulate neural repair. Recent stories in Futurism have reported that researchers, using animal models, have shown that activation of these pathways not only repaired faulty neural connections but also recovered movement and memory.

Initial experiments are exploring whether the same effects are possible in humans. Stroke patients are being treated with controlled quantities of the pill, and scientists monitor changes in brain plasticity, motor function, and cognitive abilities. The potential to restore lost capabilities via medication has generated guarded optimism among scientists.

“The early data is promising, but we’re just beginning to understand the scope of what this drug can achieve,” said one of the study’s lead researchers. “The ultimate goal is to complement or even replace traditional rehabilitation therapies.”

Optimism there is, despite challenges. Converting animal experiments to human triumphs has long been filled with stumbling blocks. Results vary considerably from person to person based on the magnitude of the brain injury and how quickly postinjury care is initiated.

Existing trials, some of which are closely monitored by The New York Times, are intended to test both safety and efficacy. Though Maraviroc has an established record of safety in its current uses, application to brain repair introduces new risks. Overactivating brain function, for instance, may precipitate seizures or other unexpected side effects.

Regulatory agencies such as the FDA are keeping close tabs. Any such breakthrough therapy will need to meet strict safety criteria before becoming widely available. Experts warn that although the prospect of a pill that can restore lost brain function has revolutionary appeal, the only course is thorough testing.

How Does The Pill Impact Brain Healing and Health?

The potential for this research goes far beyond recovery from stroke. Traumatic brain injuries caused by automobile accidents, sports injuries, or war may someday be cured with similar regenerative approaches. Researchers are also investigating whether stimulating neurogenesis could help degenerative diseases like Alzheimer's or Parkinson's disease.

New Atlas reports indicate that marrying molecular therapies with current medical devices might optimize the recovery. For instance, Stanford researchers developing clot-removing technology envision a future when physical interventions are wedded with drugs that activate the brain's inherent repair function.

The drugs industry is already monitoring the situation. With millions globally suffering from neurological conditions, the potential is huge. However, experts stress that scientific support, rather than commercial motives, should be the driving force behind the development.

For patients, a chance at a pill that will trigger brain regeneration is nothing less than revolutionary. Consider a stroke victim able to walk without a decade of agonizing therapy, or a college athlete recovering from a head injury without enduring deficits.

But whereas the promise is revolutionary, neurologists caution patience. "We're in the beginning stages," said one clinical scientist. "The science is good, the trials have started, but it will take years to be sure if this is the tipping point we all hope it will be."

The economic stakes are equally high. Stroke rehabilitation alone costs billions annually in healthcare expenses. If a pill could accelerate recovery and reduce long-term dependency, it could reshape not only medicine but healthcare systems globally.

The road from bench to bedside is long, but hopefully, it is getting shorter. A placebo-controlled, randomized trial in Canada is ongoing, and the last results are likely to be available in approximately two years. Those results will give more definite answers on whether or not brain regeneration via medication is indeed achievable.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited