- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Norovirus In UK And Flu In US Are At A Record High: What Is Making Everyone Sick?

Image Credits: Canva

This winter has seen a relentless wave of seasonal illnesses, with norovirus cases skyrocketing throughout the UK and flu cases setting records in the US. Hospitals are at capacity, emergency rooms are full, and flu outbreaks among children have resulted in school closures. The magnitude of infections is staggering, and many people are left wondering—why is everyone getting ill?

Norovirus, which is commonly referred to as the "winter vomiting bug," has been hitting the UK particularly hard this winter. The North West area is worst hit, with a daily average of 72 patients being admitted to hospital with the virus over the past two weeks. Statistics from NHS England show that hospitalizations due to norovirus have skyrocketed by 22% over the course of only one week, to an average of 1,160 patients per day. This is over twice the figure seen over the same period last year, when the norm was 509 patients per day.

Experts say that cases of norovirus normally increase throughout autumn and peak in winter, but this year, the rise came earlier and continues to increase. NHS officials point out that hospital staff are being put under huge pressure to deal with a large number of norovirus patients as well as other winter bugs.

Professor Sir Stephen Powis, the National Medical Director of NHS England, was worried about the rising infections, saying, "There is no let-up for hospital staff who are working tirelessly to treat more than a thousand patients each day with this horrible bug, on top of other winter viruses."

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, the US is having its worst flu season in more than a decade. In early February, doctor visits and hospitalizations due to the flu reached a 15-year peak. Emergency rooms are clogged, and in most states, hospitals have imposed visitor limits to stem the spread of infections.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that to date, at least 33 million individuals have contracted the flu, resulting in 430,000 hospitalizations and 19,000 deaths, of which 86 were children. The flu has resulted in a number of schools closing as a result of outbreaks, and cases continue to increase.

What's Making Everyone So Sick?

Experts say that a mix of factors is causing the high flu and norovirus cases this season. Post-pandemic socialization, lower immunity because of lower exposure in past years, and unstable vaccination rates might all be at play.

Regional Medical Director of NHS England North West, Dr. Michael Gregory, cautions that norovirus cases are still high and might keep spreading across hospitals and care homes. "We're looking to the half-term break as a break, but it's important that we all do our bit to prevent further spread," he said.

In the US, besides the flu, other viruses including COVID-19, RSV, and gastroenteritis infections are also reporting spikes. Figures from the CDC indicate that emergency room visits of RSV and COVID-19 have reduced but COVID-19 infections are high in most parts.

Identifying the Symptoms

Flu and norovirus have similar symptoms, but the way they infect the body differs.

Flu Symptoms:

- Fever

- Body aches

- Chills

- Cough

- Sore throat

- Fatigue

- Stuffy nose

- Norovirus Symptoms:

- Sudden vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Stomach cramps

- Nausea

Norovirus Symptoms:

Norovirus illnesses usually last between two and three days, compared to flu illnesses lasting a week or more. In both conditions, susceptible populations such as young children, the elderly, and those who are immunocompromised are more likely to have severe complications.

Norovirus, also called the "stomach flu," is a highly contagious infection of the gastrointestinal tract, not a respiratory virus. It transmits quickly from contaminated food and water and contact with contaminated surfaces, causing such symptoms as diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, and stomach pain.

What You Can Do to Stop Its Spread

Because of how fast both viruses spread, medical professionals highly recommend preventive actions.

For Norovirus:

- Wash hands frequently with soap and warm water, especially after using the toilet or before preparing food.

- Avoid visiting hospitals or care homes if experiencing symptoms.

- Stay home for at least 48 hours after symptoms subside to prevent spreading the virus.

For Flu:

- Get vaccinated annually to reduce the risk of severe illness.

- Avoid close contact with sick individuals.

- Practice good respiratory hygiene by covering coughs and sneezes.

- Stay home at least 24 hours after the fever has passed without the use of medication.

Dr. Gregory again emphasized the need for hygiene, saying, "Good handwashing habits can significantly reduce the spread of norovirus. Soap and warm water remain the most effective way to kill the virus."

Treatment and Recovery

Most people can be treated for flu and norovirus at home with supportive therapy. Rest, hydration, and taking over-the-counter drugs to control symptoms are the road to recovery.

For flu, antiviral drugs like Tamiflu may prevent more severe symptoms from occurring if taken within 48 hours of symptom onset. The CDC advises high-risk groups to seek advice from their physicians regarding antiviral medication.

For norovirus, hydration is crucial, as diarrhea and vomiting have the potential to cause rapid dehydration, especially in children and the elderly.

Flu season in the US remains at its peak, and UK norovirus cases are still on the increase. Although some experts are optimistic that cases will decrease by spring, the unpredictability of viral outbreaks dictates that caution must be maintained.

Hospitals and healthcare facilities are calling on people to adhere to preventive measures in order to mitigate the burden on medical resources. Vaccination, hygiene, and self-isolation when ill continue to be the best lines of defense against such illnesses.

Delhi Kidnappings Were False Fear Mongering, Officials Confirm

Days after it emerged that over 800 people had gone missing in Delhi during the first 27 days of 2026 and officials requested people to remain calm, Delhi Police has revealed this is false and such claims are being "pushed through paid promotion".

In a statement released on X today morning: "After following a few leads, we discovered that the hype around the surge in missing girls in Delhi is being pushed through paid promotion. Creating panic for monetary gains won't be tolerated, and we'll take strict action against such individuals."

Authorities across the capital claim that dispensing false information about life-altering information such as kidnappings and death through paid promotion can cause as well as amplify fear among the general public, which can massively ruin mental health and cause long-term damage to overall wellbeing.

Dr Kunal Bahrani, Chairman and Group Director, Neurology at Yatharth Hospitals, explained to Healthandme: "Incidents like this highlight how quickly fear can spread in today’s hyperconnected world and how deeply false news can impact mental wellbeing. When people are exposed to alarming information, especially involving safety and crime, the brain’s threat system switches on almost instantly. Stress hormones such as cortisol surge, increasing anxiety, restlessness, sleep disturbances and even physical symptoms like headaches or heart palpitations.

"Repeated exposure to frightening but unverified news can also condition the brain to remain in a constant state of alert, making individuals more irritable, emotionally overwhelmed and prone to panic. For children, elderly people and those already struggling with anxiety or depression, the psychological impact can be far more intense and long-lasting."

However, while many wonder how this form of promotion came into being, Reddit users are already pointing towards Rani Mukerji's Mardaani-3, a movie based on the kidnapping of minor girls as the source for this chaos.

How Does Fear Mongering Ruin Mental Wellbeing?

Fear-mongering severely impacts mental health by triggering chronic stress, anxiety, and depression, often overloading the brain’s threat response system (amygdala) and leading to long-term damage.

Over time, constant exposure to exaggerated, alarming narratives fuels irrational fears and cognitive distortions such as catastrophizing. This constant state of fear can also lead to avoidance behaviors, hopelessness, and physical symptoms like headaches, poor sleep and a weakened immune system.

Dr Neetu Tiwari, MD Psychiatry Senior Resident, NIIMS Medical College & Hospital also told Healthandme: "When things like this happen around us, it creates a sense of panic and fear amongst parents and children. Our brain usually reacts as if the danger is real. The body then becomes alert, our heart beats faster than it should, and our mind stays at tense. Even if the news is proven to be false, this fear that has set in often takes time to settle down.

"Now this in turn causes a lot of trouble. It makes people feel unsafe, so people avoid going out, they worry more about loved ones, or may also keep checking their phones repeatedly for updates. This behavior can lead to anxiety, panic, disturbed sleep, and constant overthinking. Even when the news is fake, fear travels very quickly. And once fear enters our mind, calming down takes time.

"This is why sharing unverified information can unknowingly harm others especially children as it can lead them in feeling scared even to go to school, or sleep alone, or even step outside. In fact in some children this may even cause nightmares or these children become unusually clingy to parents or guardians which further leads to problem in social development and confidence.

Dr. Rajiv Mehta, senior consultant psychologist, Sir Gangaram Hospital added: "The society at large is very gullible and anxiety prone, as we have seen the rise in mental illnesses. The people who are already anxious will get more anxious, the people who are not anxious will get anxious and that will increase the mental instability in the persons.

"And what they and parents are going to do is take a lot of precautions towards their young kids by not allowing them to go outside, to play with the children and go out of society buildings. They will be very fearful and when children will be home bound, then they will spend more time on screens or will have altercations with their parents.

"People should not resort to such kind of things only for the sake of their own materialistic monetary benefit. That is highly condemnable if it has occurred because of these kind of reasons that movie is going to release and they are sensationalizing these things."

Are The Delhi Kidnappings False?

Data obtained from Press Trust of India suggests that a total of 807 people went missing between January 1 and 15, with an average of 54 people going missing every day. Of these, 509 were women and girls, and 298 were men. Among the total reported missing, 191 were minors and 616 were adults.

In an official statement, the police said that, while the data was recorded, January 2026 saw a "decline in the number of missing persons reports when compared with the corresponding period of previous years."

Officials had previously further clarified that no organized gang or criminal network has been found involved in cases of missing or abducted children in Delhi so far.

"Recent public discourse has raised concerns about the welfare of children in Delhi. We appeal to the citizens not to fall prey to the rumours about the spurt in the cases of missing children.

While denying such claims, we also warn rumour mongers of strict legal action for creating unnecessary panic and fear by misrepresenting data.

The safety of every child is of paramount importance to Delhi Police.

"Delhi Police is committed to serve 24x7 and making all out efforts to trace all missing persons and reunite them with distraught family members, at the earliest," they said in a statement released yesterday.

Cheaper Copy Of Wegovy Pill By Hims & Hers Now Available For 49, Novo Nordisk Says It Will Take Legal Actions

Credits: iStock

Cheaper copy of Wegovy by Hims & Hers for $49 has drawn tensions, with Novo Nordisk now approaching to take legal actions. The pill by Novo Nordisk is sold for $149. In a statement, Novo said, "The action by Hims & Hers is illegal mass compounding that poses a significant risk to patient safety. Novo Nordisk confirmed that the company will take legal and regulatory actions to protect patients.

“Novo Nordisk will take legal and regulatory action to protect patients, our intellectual property and the integrity of the US gold-standard drug approval framework. This is another example of Hims & Hers’ historic behaviour of duping the American public with knock-off GLP-1 products, and the FDA has previously warned them about their deceptive advertising of GLP-1 knock-offs,” the statement said.

Read: Wegovy Pills Now Available At Your Pharmacies, Here's What To Know About Its Usage

Cheaper Copy Of Wegovy Pill: What Unveiled Afterwards?

After the cheaper copy of the pill was launched by Hims & Hers, shares of Novo Nordisk and rival Eli Lilly fell by 7%. Whereas, stock for Hims & Hers initially spiked after the announcement, but pared gains after Novo said that it would fight the rollout.

Hims & Hers was previously offering compounded semaglutide, the active ingredient in Novo Nordisk's popular weight loss drug Ozempic and Wegovy, in injectable format. The company has now extended to offer the oral version.

Cheaper Copy Of Wegovy Pill: How Much Does This Cost?

Hims & Hers said that the Wegovy copy pill cost $49 for the first month and $99 with a 5-month plan. While semaglutide's patent is protected in the US until 2032, however, Hims & Hers claim that the copies are 'personalized' and therefore legal.

“This compounded product uses a different formulation and delivery system than FDA-approved oral semaglutide,” Hims & Hers said. “This once-a-day pill has the same active ingredient as Wegovy and empowers providers to tailor treatment plans specifically for those who prefer to avoid needles or need smaller doses to help to balance side-effects,” it said.

Cheaper Copy of Wegovy Pill: Novo Nordisk Rejects Hims & Hers Claims

Novo Nordisk however, highlighted that it manufactures Wegovy pill by using SNAC technology. This technology helps in absorption when administered orally. Therefore, it is not clear how Hims & Hers copy formula could match that level of absorption.

Last year, Novo Nordisk and Hims & Hers partnered to offer weight loss jabs at a discounted price to telehealth company's customer. However, Novo Nordisk ended the collaboration just two months later, stating that Hims & Hers used 'deceptive' marketing that put patient safety at risk

Cheaper Copy of Wegovy Pill: Does Eli Lilly Have A Weight Loss Pill Yet?

While rival Eli Lilly does not have the weight loss pill yet, it is expected to launch orforglipron in the first half of this year. The pill is currently pending Food and Drug Administration approval.

Read: Eli Lilly Sends Weight-Loss Pill For Approval: Is Oral GLP-1 As Effective As The Injections?

“With the ... current legal backdrop, there is no reason why HIMS shouldn’t evaluate these launches for every subsequent weight loss product as the market continues to evolve,” Leerink analyst Michael Cherny said in a note to clients.

TrumpRx Is Live: How Is It Changing US Healthcare System? Explained

Credits: Wikimedia Commons and Canva

TrumpRx is live. President Donald Trump on Thursday announced the launch of TrumpRx, a direct-to-customer website that will lower prescription drug costs in the US.

As per the president, millions of Americans would save money through this platform. However, it is still unclear if all patients, especially those with insurance coverage will see more cost saving while using this website to buy their medicines.

TrumpRx is for people willing to pay cash and forgo insurance, which means people without or with limited coverage could benefit.

"You are going to save a fortune and this is also so good for overall health care," said Trump at the TrumpRx launching night on Thursday.

TrumpRx Is Live: How Does It Work?

TrumpRx does not sell drugs directly to American patients, rather acts as a central hub that points them to drugmakers who are offering discounts. For instance, Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk were already offering their popular weight loss drugs at hefty discounts, TrumpRx would further give them discount coupons and redirect them to their website.

This means if someone clicks on Eli Lilly's Zepbound offer, it will send them directly to the company's platform, where the person must submit prescription details.

TrumpRx Is Live: Which Drugs Are Now Cheaper?

At launch, the site only featured medications from five companies, which are:

- AztraZeneca

- Lilly

- EMD Serono

- Novo Nordisk

- Pfizer

However, as per a White House fact sheet, TrumpRx will list drugs from other companies "in coming months".

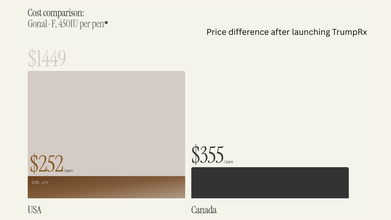

TrumpRx marks the government’s latest attempt to curb soaring prescription drug prices in the US, which are on average two to three times higher than in other developed countries and can be up to 10 times costlier than in some nations, according to public policy think tank Rand Corp.

TrumpRx Is Live: Is It Really Beneficial?

TrumpRx “doesn’t appear to be a one-stop solution” to high drug costs for most Americans, said Juliette Cubanski, deputy director of the Program on Medicare Policy at KFF, a health policy research organization. While cash-pay options may offer better value for people without insurance, it remains unclear how many individuals would actually benefit from TrumpRx, she noted.

“If someone can already access a medication through their insurance with a relatively affordable copay, there isn’t much added advantage to using the TrumpRx website,” Cubanski said.

She also pointed out that insured consumers who purchase medicines through direct-to-consumer platforms may find those purchases do not count toward their insurance benefits, meaning they do not help meet deductibles or out-of-pocket maximums.

At the same time, Cubanski said TrumpRx could play a role in improving access to certain drugs at lower prices, especially medications that are not widely covered by insurance in the US, such as obesity treatments. Medicare is set to cover weight-loss drugs for the first time later this year under agreements struck by Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk with Trump, though many employers remain reluctant to include these medicines in their coverage.

However, she added that many other drugs expected to be offered on TrumpRx are already commonly covered by insurance, and several are also available as lower-cost generics from rival manufacturers.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited