- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Rare 100% Deadly Brain Disease Kills Two In Oregon County, Third Infection Confirmed

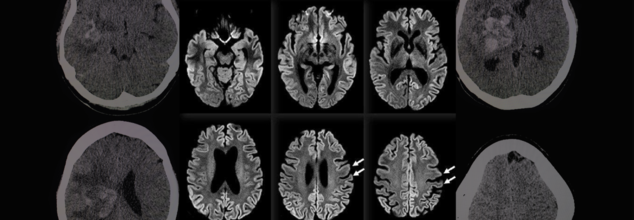

A rare and fatal brain disease with a 100% mortality rate has gripped Hood River County, Oregon, raising concerns within the medical community and eliciting intense probes by local and federal health officials. It is called Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD), and it has killed two people and impacted a third in eight months—a terrifying cluster in a county of only slightly more than 23,000 people.

On April 14, the Hood River County Health Department reported one case of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease and two more probable cases. Although only one case has been confirmed by a diagnosis through an autopsy, the other two are presumptive and await post-mortem confirmation through examination of brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid. Such examination, as explained by Trish Elliott, Director of the Hood River County Health Department, may take months.

Although the origins of these three cases are still unknown, the cluster is epidemiologically significant. The U.S. experiences about 350 cases of CJD each year, or 1 to 2 cases per million individuals globally. For Hood River County, with only 23,000 people, to see three cases over such a brief time span is an epidemiologic outlier.

What Is Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD)?

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease is a rapidly advancing and always lethal neurodegenerative disease resulting from misfolded proteins known as prions. Initially documented in the 1920s by German physicians Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt and Alfons Jakob, CJD causes sponge-like holes to form within the brain, destroying its structure and function.

CJD is a member of the larger family of prion diseases, which also encompasses other rare but fatal disorders like kuru and fatal familial insomnia. Similar to bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), commonly referred to as mad cow disease, CJD irreversibly destroys the brain and has no cure.

CJD Symptoms and Progression

The symptoms of CJD are extreme and worsen quickly. Early symptoms may involve confusion, disorientation, personality changes, memory loss, visual disturbances, and stiffness of the muscles. Later in the disease, patients can develop hallucinations, difficulty speaking or swallowing, seizures, and sudden jerky movements.

Death typically occurs within a year of the onset of symptoms, usually as a result of complications such as pneumonia, heart failure, or problems arising from neurological deterioration such as falls and choking.

Symptoms in the early stages of sporadic CJD usually resemble other dementias but worsen with terrifying rapidity. The majority of individuals with sporadic CJD are between 50 and 80 years of age, but some genetic forms can occur earlier, even in some people as young as 30.

Various Types of CJD

CJD comes in several types:

Sporadic CJD (sCJD): This type is the most prevalent, affecting about 85% of the cases. This type happens spontaneously when healthy proteins in the brain misfolded into prions for unknown reasons.

Genetic CJD (fCJD): Due to mutations in the PRNP gene, this form is inherited and represents about 10–15% of the total cases. The PRNP gene codes for the prion protein (PrP), a protein involved in neuronal communication and protection.

Acquired CJD (also referred to as iatrogenic or variant CJD): This is a rare type that involves outside sources of infection, such as eating infected beef (BSE/mad cow disease) or through tainted medical equipment or transplanted tissue.

In spite of concerns, authorities from Hood River County stressed that the present cases do not seem to have resulted from infected cows. "At this point in time, there is no cause identified between these three cases," the department noted. They also pointed out that CJD cannot be transmitted via air, touching, social contact, or water.

Public Health Measures and Continued Investigations

The Hood River County Health Department, in collaboration with the Oregon Health Authority and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), has launched an "active and ongoing investigation" into the three reported cases.

“We’re trying to look at any common risk factors that might link these cases,” Trish Elliott told The Oregonian. “But it’s pretty hard in some cases to come up with what the real cause is.”

Although risk to the general population is "extremely low," the health department continues to monitor it. Since CJD cannot be definitely diagnosed until after death, real-time monitoring is not easy, and so robust surveillance is essential.

Can CJD Be Prevented?

Although there is no treatment or cure to prevent the development of CJD, the U.S. has established strict public health measures to minimize the risk of acquired CJD, especially through food supply control and medical safety measures.

Federal authorities have maintained since the 1990s a prohibition against feeding cattle which could be contaminated with BSE, and employment of high-risk material in foods is strictly barred. Sterilization processes of surgical devices as well as strict donor screening in transplantation and transfusions are all undertaken to cut back on iatrogenic spread.

While medical officials wait for further verification and possible connections between the three patients, the attention is on education, surveillance, and reassurance to the public.

Although it is reassuringly ominous to witness a disease of this kind emerging in a small American community, the risk at the international level remains low, especially with measures presently in place. Nevertheless, the cases are a sobering reminder of the enigma that prion diseases continue to pose to modern medicine.

Health officials are still keeping an eye on the matter and are asking people not to panic but to remain updated. "The health department will remain vigilant and inform you of any public health risk," officials promised in a statement.

Tennis Player Monica Seles Opens Up About Her Myasthenia Gravis Diagnosis

(Credit-monicaseles10s)

Tennis great Monica Seles, in an interview with Associated News, recently shared that she was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis (MG) three years ago. This is the first time she's spoken publicly about the disease, which is a rare condition that causes muscles to become weak.

Seles, who won nine major tennis titles, first noticed something was wrong while hitting tennis balls. She said she started seeing two balls instead of one and felt a sudden weakness in her arms and legs. She also mentioned that simple things like blowing out her hair became very difficult.

Seles said it was hard for her to accept the diagnosis at first. She decided to speak out to help others, hoping her story will bring more attention to myasthenia gravis. Before she got her diagnosis, she had never heard of the condition.

What Is Myasthenia Gravis?

Medscape explains that myasthenia gravis is a chronic neuromuscular disease. This means it's a long-term illness that affects the way your nerves and muscles work together. It causes weakness in the muscles that you can control, such as those in your arms, legs, and face. While it can affect people of any age, it is most common in:

- Young women under 40

- Older men over 60

Symptoms of Myasthenia Gravis

The most common symptoms of MG are:

- Visual problems which includes drooping eyelids and seeing double.

- Your muscles might feel weak and tired very quickly, and this can change from day to day or even hour to hour.

- Your facial muscles can become weak, which may make a smile look more like a snarl.

- Difficulty speaking or swallowing, you might also have trouble pronouncing words or swallowing food.

- Weakness in the neck or limbs like your arms, legs, or neck may feel weak

The symptoms of MG can sometimes look like other conditions, so it's always important to see a doctor for a proper diagnosis. People with MG may experience periods when their symptoms get worse (flare-ups) and periods when they get better (remission), but the condition is rarely cured completely.

How is Myasthenia Gravis Diagnosed?

To figure out if you have MG, your doctor will ask about your symptoms and medical history. One key way they test for it is by giving you a specific medicine. If your muscle weakness quickly gets a lot better after taking the medicine, it's a strong sign that you have MG.

Doctors might also use other tests. They can do blood tests to look for certain antibodies that are common in people with MG. They might also use nerve and muscle tests to see how your nerves are sending signals to your muscles and to measure your muscle's electrical activity.

Treatment and Management of Myasthenia Gravis

While there's no cure for MG, the symptoms can be controlled. The main goal of treatment is to make your muscles stronger and prevent problems with breathing and swallowing. Most people with MG can live normal or close-to-normal lives with the right care.

Treatment often includes medicine, such as drugs that control the immune system or help your muscles work better. Sometimes, a doctor may suggest surgery to remove the thymus gland, which can help reduce symptoms for many people. Other treatments, like plasmapheresis, can be used to remove the bad antibodies from your blood.

Can You Prevent Myasthenia Gravis?

To help prevent a myasthenia crisis, you should always take your medicines exactly as prescribed. It can also help to take your medicine 30 to 45 minutes before meals to prevent food from getting into your lungs.

Try to avoid getting sick by staying away from people with colds or the flu, and make sure you get proper nutrition, rest, and manage your stress. It is also very important to always tell your doctors about your MG diagnosis and the medicines you are taking before they prescribe you anything new. Some medicines can interfere with your condition or your treatment.

The most serious complication of MG is a myasthenia crisis. This is when you have extreme muscle weakness, especially in the muscles you need to breathe. This is a medical emergency and may require help from a breathing machine.

Seles, who is 51, said she has learned to live with a "new normal." She sees this challenge as just another "reset" in her life, similar to when she moved to the U.S. as a young teenager or when she was recovering from a stabbing. Her message is one of strength and a reminder to always adjust, just like a tennis player on the court.

If You Are Scared Of Needles, Scientists May Have A 'Painless' Dental Solution For Your Next Vaccine

Credits: Canva

For decades, getting vaccinated has meant rolling up your sleeve, bracing for a quick jab, and hoping the soreness fades within a day. But a team of researchers may have just discovered a way to sidestep the needle entirely — by delivering vaccines through something as ordinary as dental floss.

The idea sounds almost too simple: coat floss or a floss pick with a vaccine, thread it between your teeth, and let your gums do the rest. But the science behind it is far from gimmicky. This novel approach targets a unique spot in the mouth called the junctional epithelium, an unusually permeable layer of tissue where the gums meet the teeth. And according to early research, this entry point could unlock stronger protection against respiratory infections — and for some people, make getting vaccinated a far less stressful experience.

Most viruses that wreak havoc on the body, including influenza and COVID-19, first invade through the mucosal surfaces of the mouth, nose, or lungs. Traditional injectable vaccines do an excellent job of generating antibodies in the bloodstream, but they’re less effective at producing antibodies along these mucosal barriers — the body’s first defense line.

Dr. Harvinder Singh Gill, a professor in nanomedicine at North Carolina State University and senior author of the study, explains the advantage: “When a vaccine is given via a mucosal surface, antibodies are stimulated not only in the bloodstream but also on mucosal surfaces. This improves the body’s ability to prevent infection, because there’s an additional line of defense before a pathogen even enters the body.”

That’s where the junctional epithelium comes in. Unlike most epithelial layers that are tightly sealed to keep invaders out, the JE is intentionally “leaky” so immune cells can patrol and defend against the constant barrage of oral bacteria. This leakiness is exactly what makes it an appealing vaccine delivery route.

To test the concept, researchers applied a peptide-based flu vaccine to unwaxed dental floss, then used it to floss the teeth of lab mice. The results were striking. The floss-based delivery triggered far higher antibody responses on mucosal surfaces than the current gold-standard oral method — placing a vaccine under the tongue.

In fact, the immune protection was comparable to delivering the same vaccine through the nasal cavity, which is widely considered the most effective mucosal route. The big difference? Nasal vaccination comes with safety concerns, including the rare but serious possibility that the vaccine could migrate to the brain. The floss technique avoids that risk entirely.

Lead author Rohan Ingrole, who conducted the research during his doctoral studies at Texas Tech University, adds that the method also worked across multiple vaccine types — including protein-based vaccines, inactivated viruses, and mRNA formulations. In each case, the floss delivery triggered robust immune responses both in the bloodstream and across mucosal surfaces.

What Is the Junctional Epithelium?

The JE sits deep in the gum pocket, where it forms a protective seal between the tooth and surrounding gum tissue. Its structure lacks many of the tight junctions found in other mucosal linings, making it easier for molecules — including vaccine antigens — to cross. And because it’s already brimming with immune cells, any antigen that slips through is quickly flagged, sparking an immune reaction.

Delivering a vaccine here isn’t straightforward. The tissue is tucked away and can’t be reached with a simple swab or spray. Dental floss, however, is designed to slip into exactly that space — which is why it’s the perfect vehicle for the job.

Flossing Vaccine Shows Success In Early Human Trials

While full-scale human vaccine trials are still a way off, the researchers ran a smaller test to confirm whether people could successfully target the junctional epithelium using floss picks. They coated floss with fluorescent food dye and asked 27 volunteers to try to deposit the dye into their gum pockets. The results were encouraging: about 60% of the dye ended up exactly where it needed to be.

This success suggests that with the right design, floss picks could be a practical, self-administered vaccine delivery tool — potentially mailed to people’s homes in the future.

Needle-free vaccination is more than just a comfort perk. Globally, needle phobia is a significant barrier to vaccine uptake, even among adults. There’s also the risk of unsafe injection practices, which can transmit blood-borne diseases in settings without strict medical oversight.

A floss-based vaccine could address several of these challenges. It’s simple to administer, doesn’t require a healthcare professional, and could be distributed more easily in hard-to-reach areas. Storage and transport could also be simplified compared to injectable vaccines that require strict cold-chain logistics.

Dr. Gill notes another advantage: eating and drinking immediately after floss-based vaccination doesn’t appear to interfere with the immune response — at least in animal models. That flexibility could make it easier for people to incorporate vaccination into daily routines without major disruptions.

Are There Any Limitations to Such Vaccines?

Despite the promise, this approach isn’t without drawbacks. It wouldn’t work for infants or toddlers without teeth, and it may be less effective for people with gum disease or severe oral infections. Researchers also need to study how different oral health conditions could influence vaccine uptake and immune response.

For now, the team’s next step is to refine the delivery system and begin clinical safety trials. If successful, floss-based vaccines could become an alternative option for seasonal flu shots, pandemic preparedness, and even certain routine immunizations.

The floss vaccine fits into a growing push to move beyond injections. Researchers have explored dissolvable microneedle patches, inhalable vaccines, and even edible vaccine capsules. Each approach aims to make vaccination less invasive, easier to distribute, and more acceptable to populations hesitant about traditional methods.

In this case, the innovation comes from using a tool that people already know and can use on their own. The fact that it could also boost mucosal immunity something standard injections struggle to do — makes it even more compelling.

We’re still years away from picking up a vaccine-coated floss pick at the pharmacy, but the groundwork is being laid. If clinical trials confirm its safety and effectiveness, floss-based vaccination could offer a new, accessible, and needle-free way to protect against some of the world’s most common and dangerous infections.

FDA Vaccination Chief Vinay Prasad Returns To Job Within Days After Quitting Under Pressure, Who Is He?

Credits: vinaykkprasad.com

Dr. Vinay Prasad, who resigned just two weeks ago as head of the Food and Drug Administration’s vaccines and gene therapy division, is returning to the agency in a rare reversal. The Department of Health and Human Services confirmed his reinstatement on Saturday, with spokesperson Andrew Nixon saying Prasad will resume leadership of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the FDA’s request.

Prasad’s ouster in late July followed sustained pressure from biotech executives, patient advocacy groups, conservative figures, and right-wing activist Laura Loomer. Loomer, who has previously demonstrated influence over Trump administration personnel decisions, accused Prasad of being a “progressive leftist saboteur” and, more recently, a “Marxist,” pointing to his past praise for Senator Bernie Sanders.

Resignation Amid Political and Public Backlash

The decision to push him out came after weeks of mounting criticism, fueled in part by a series of editorials faulting him for denying drug approvals and ordering a pause on a medication linked to several patient deaths. Loomer and other critics also drew attention to comments Prasad had made about Donald Trump before joining the administration.

Before his resignation on July 29, both Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and FDA Commissioner Dr. Marty Makary defended Prasad, calling him a scientist of exceptional rigor. Makary publicly described him as “impeccable,” while Kennedy privately noted his preference for Prasad’s cautious approach to vaccine approvals.

A Record of Tough Regulatory Calls

Since joining the FDA, Prasad has drawn attention for decisions that prioritized safety and efficacy over speed. He declined to approve multiple high-profile drugs, including treatments for advanced skin cancer and heart conditions in patients with a rare muscle disorder, arguing that the agency should resist approving high-cost drugs with uncertain benefits.

In May, he played a key role in limiting the use of COVID-19 vaccines to those over 65 and people with health conditions that put them at greater risk of severe illness. Under his leadership, the FDA restricted approvals for new shots from Novavax and Moderna and set stricter testing requirements for future vaccines.

His most controversial move came when he ordered the halt of Sarepta Therapeutics’ gene therapy shipments for Duchenne muscular dystrophy after two teenage boys and a 51-year-old man died in cases deemed related to the medication. The decision met fierce resistance from families of patients and advocates for expanded access to experimental treatments, as well as criticism from political figures and editorial boards. The FDA later reversed the suspension, allowing shipments for younger patients to resume.

A History of Outspoken Criticism

Before his government role, Prasad was an oncologist and epidemiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, where he gained a large following through Substack, YouTube, and other platforms. Known for sharp and sometimes expletive-laced critiques of public health policy, he frequently challenged the FDA’s pandemic-era decisions and called for greater scrutiny of medical products.

His reinstatement underscores the influence Kennedy and Makary still hold within the Trump administration and signals that, despite political headwinds, Prasad’s hardline approach to drug and vaccine oversight will continue to shape U.S. healthcare policy.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited