- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Salmonella Outbreak Triggers Massive Egg Recall Across 7 States

Credits: Canva

A salmonella outbreak linked to a large egg recall has sickened dozens of people across seven U.S. states in the West and Midwest, federal health officials confirmed on Saturday.

Egg Recall Affects Over a Million Eggs

The August Egg Company has recalled approximately 1.7 million brown organic and brown cage-free eggs distributed to grocery stores between February and May. The recall was issued due to potential salmonella contamination, as stated in an announcement posted on the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) website on Friday.

States Impacted and Reported Cases

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), at least 79 people across seven states have been infected with a strain of salmonella traced back to the recalled eggs. Of these, 21 individuals have been hospitalized. The recall affects the following states: Arizona, California, Illinois, Indiana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Nevada, Washington, and Wyoming.

Consumers are advised to check the FDA and CDC websites for a full list of affected brands, plant codes, and Julian dates to identify whether the eggs they have purchased are part of the recall.

Recognizing Salmonella Symptoms

Salmonella infection can cause a range of symptoms, including diarrhea, fever, stomach cramps, severe vomiting, and dehydration. While most healthy individuals recover within a week without medical intervention, the illness can become more serious in certain groups.

High-Risk Groups Urged to Take Precaution

Young children, older adults, and individuals with weakened immune systems are at a higher risk of severe illness and may require hospitalization. Health officials urge anyone experiencing symptoms after consuming eggs to seek medical attention promptly.

Ongoing investigations are being conducted to determine the full scope of the outbreak and ensure contaminated products are removed from shelves.

Previous Outbreaks

The Health and Me has previously also reported on various Salmonella outbreaks happening in the US, including the outbreak caused by tomatoes, which has led to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issue a Class I recall, also considered the highest warning label.

Class I recall means that there is a reasonable change that using the product could lead to "serious adverse health consequences or death".

Another outbreak was linked to Florida-grown cucumbers about which the CDC has also warned the population.

Very similar to what is happening now, another Salmonella outbreak was linked with backyard poultry and products like eggs, noted the CDC.

What Is Salmonella?

As per the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA), Salmonella are a group of bacteria that can cause gastrointestinal illness and fever called salmonellosis. It can be spread by food handlers who do not wash their hands and/or the surfaces and tools they use between food preparation steps. It can also happen when people consume uncooked and raw food. Salmonella can also spread from animal to people.

FDA notes that people who have direct contact with certain animals, including poultry and reptiles can spread the bacteria from the animal to food if hand washing hygiene is not practiced.

Pets too could spread the bacteria within the home environment if they eat food contaminated with Salmonella.

'Kissing Bug' Chagas Disease Causes More Disabilities Than Malaria And Zika: Study Reveals

(Credit- CDC)

Despite affecting 6 million people globally, this disease is considered to be a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization. This disease is the Chagas disease, more popularly known as the ‘kissing bug’ disease.

However, health experts have noted that people who contracted the Chagas disease are not getting the help they need. The September report published by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that although Chagas is considered an endemic in 21 countries of the Americas except United States. However, what does this mean?

The CDC September report explains that US not naming Chagas an endemic, means it's a constant, local issue. This official label is misleading because there's a lot of evidence that the disease is right here in the U.S., too.

The reason why this is a big cause of worry for people is because of how dangerous the disease actually is. A report published in the 2019 Current Tropical Medicine Reports, showed that Chagas disease (CD) is a serious, often overlooked health condition caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. They explained how it is more disabling than other parasitic infections like malaria and Zika.

The report also detailed how it was considered a leading cause of heart disease in the Americas and affects over 6 million people globally, with more than 90% of cases in Latin America. The disease leads to over 7,500 premature deaths and an annual global economic cost of $8 billion.

How Many States Are Affected With Chagas Disease?

The CDC report explains that the disease is spread by blood-sucking "kissing bugs" which are found in 32 states across the southern U.S. While we don't know for sure if the number of bugs is increasing, we do know that people are encountering them more often.

- 9 out of 11 types of kissing bugs in the U.S. are naturally infected with the parasite that causes Chagas disease.

- Four of these species are commonly found in and around homes, which increases the chance of them spreading the disease to humans.

- Studies show that 30% to over 50% of kissing bugs in the U.S. carry the parasite.

Can Animals Have Chagas Disease?

The parasite isn't just in bugs; it's also common in animals across the southern U.S. Wild animals like raccoons, opossums, and armadillos carry the parasite and can pass it on to kissing bugs. This creates a cycle where the parasite can continue to spread. Dogs are also a major concern.

They've been found with the infection in 23 states, and in Texas, where animal cases were once tracked, hundreds of cases were reported in just a few years. Even zoo animals and research primates have been found to be infected. This shows that the parasite is widespread and well-established in the environment here.

How Many States Have Been Affected By Chagas Disease?

It’s clear that people are getting Chagas disease from local sources in the U.S. The disease has been found in humans in at least 8 states, with the most cases documented in Texas. Since 2013, Texas has reported 50 cases that were likely acquired within the state, not from travel.

The actual number of human cases is probably much higher because Chagas disease is not officially tracked nationwide. Only a handful of states require doctors to report cases, so many go unnoticed and uncounted. The CDC report explains why calling the US "non-endemic" for Chagas disease creates major problems.

- Doctors don't think to test for it. They are often unaware that people can get the disease locally, which leads to missed diagnoses.

- Public awareness is low. People don't know to look out for kissing bugs or the symptoms of the disease.

- It limits funding and research. By not recognizing the problem, the U.S. can't fully work on a national strategy to fight it.

How Does Naming Chagas ‘Endemic’ Help US?

The report says that officially classifying Chagas disease as endemic in the U.S. will help, but it should be specifically labeled as a "hypoendemic" problem, which means it's present at low but consistent levels. This new label would:

- Help doctors better understand the risk and diagnose the disease.

- Increase funding for research and public health programs.

- Allow us to create a plan to track cases and prevent new infections.

Not Just COVID-19, Or Hepatitis B, Kennedy's New Vaccine Committee Plans To Change Chickenpox, Measles, Mumps And Rubella Shots

RF Kennedy Jr, Health Secretary, Source: AP

The future of childhood vaccinations in the U.S. is suddenly in question. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s newly restructured vaccine advisory committee is set to vote this week in Atlanta on whether to alter long-standing recommendations for several critical vaccines, including shots against chickenpox, measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis B, and COVID-19.

The committee, known as the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), plays a powerful role: its recommendations guide pediatricians nationwide and determine which shots are covered by the government-funded Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, a safety net for low-income families.

While some experts say the agenda looks like a routine review, others worry it could open the door to unnecessary confusion, weaken trust, and reduce access to vaccines that have long protected children from serious disease.

Also Read: Unique Symptoms Of Covid In 2025 And How Long Infection Now Last

Chickenpox and the MMRV Vaccine Debate

Before the chickenpox vaccine was licensed in 1995, nearly every American child contracted the disease. While often dismissed as a rite of passage with itchy rashes and mild fevers, chickenpox could also lead to severe complications like pneumonia, skin infections, brain swelling, and in rare cases, death. The virus, varicella, also lingers in the body and can resurface decades later as shingles, a painful nerve condition.

The introduction of the vaccine dramatically reduced cases and hospitalizations. In 2005, regulators approved a combination shot called MMRV, which bundled measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccines into a single injection. Initially, health officials recommended the combo as the preferred option for the first dose in toddlers.

However, studies soon revealed a catch: children who received the MMRV shot were more likely to develop fevers, rashes, and in rare instances, febrile seizures compared with those who got separate MMR and varicella injections.

In response, the ACIP in 2009 updated its guidance, recommending separate shots for the first dose (typically given between ages 12–15 months) but allowing the combo shot for the second dose in preschool years.

Today, most pediatricians follow that approach. Still, the evidence hasn’t changed in over a decade. That raises eyebrows about why the Kennedy-led committee is reopening the debate now.

Public health experts caution that limiting the combined shot could make vaccination less convenient for families and potentially reduce uptake. Pediatric advisors warn that even small barriers, like two shots instead of one, can mean some kids fall behind.

Why Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Still Matter

While much of the attention is on chickenpox, the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine remains equally critical. Each of these viruses was once a common threat in childhood:

- Measles can lead to pneumonia, brain swelling, and death.

- Mumps can cause meningitis and, in boys, permanent infertility.

- Rubella is especially dangerous for pregnant women, sometimes causing miscarriage or severe birth defects.

Before widespread vaccination began in the 1970s, hundreds of thousands of children in the U.S. contracted these diseases every year. Outbreaks have returned in recent years when vaccination rates dip, underscoring the importance of reliable and consistent recommendations.

Revisiting guidance without new evidence, experts say, risks fueling skepticism among parents already facing a flood of misinformation online.

The COVID-19 Vaccine Question

The COVID-19 shots are also on the table. Typically, ACIP renews recommendations annually for vaccines against respiratory viruses such as flu. But this June, Kennedy’s panel endorsed flu vaccines while staying silent on COVID-19.

Also Read: US Health Officials To Examine Covid Vaccine Effects In Pregnant Women And Kids

That silence matters. Earlier, Kennedy had already removed COVID-19 shots from CDC recommendations for healthy children and pregnant women, sparking lawsuits from pediatric groups who said the move endangered kids’ health.

The FDA recently narrowed the authorization of updated COVID-19 vaccines, limiting use for certain younger groups. If ACIP mirrors that without clarification, millions of children could lose federally funded access through the Vaccines for Children program. Experts warn this could leave families confused, especially since COVID-19 formulations update yearly, much like flu shots.

Revisiting Hepatitis B Vaccinations

Hepatitis B presents a different set of challenges. The virus can cause chronic liver infection, cirrhosis, and cancer. While adults often acquire it through sexual contact or sharing needles, newborns face the highest lifelong risk if exposed at birth.

Since 2005, U.S. guidance has recommended that infants receive their first hepatitis B shot within 24 hours of birth. This approach significantly reduced cases of mother-to-child transmission, which often slipped through maternal screening programs. Studies show the newborn shot is safe and highly effective, preventing 85–95% of chronic infections.

Yet Kennedy’s committee has floated the idea of revisiting this recommendation, though experts note there is no new evidence suggesting safety concerns. Critics argue that questioning the birth dose now could reverse decades of progress.

Why the Stakes Are So High

Beyond the science, the politics surrounding these deliberations are unusual. Kennedy, once one of the nation’s most vocal vaccine skeptics, dismissed the 17-member ACIP earlier this year and replaced it with a panel that includes several anti-vaccine voices.

Historically, ACIP’s recommendations are based on careful review by subcommittees made up of pediatricians, infectious disease experts, pharmacists, and public health officials. Those subgroups sift through peer-reviewed studies, track outbreaks, and balance risks against benefits. But this time, critics say the process appears less about science and more about ideology.

Even if the committee doesn’t overturn long-standing guidance, simply reopening settled debates may erode confidence. Parents who hear that vaccines are “under review” might delay or decline shots, leaving children vulnerable.

Perhaps most worrisome: a restrictive vote could block coverage of these vaccines under the Vaccines for Children program, which supplies nearly half of all childhood shots in the U.S. Without it, low-income families could lose access, widening gaps in protection.

What Lies Ahead?

The stakes of this week’s ACIP votes go far beyond the meeting room in Atlanta. At issue is not just whether a child gets one shot or two, but whether the nation maintains decades of progress against diseases once considered inevitable.

Chickenpox, measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis B, and COVID-19 vaccines have all proven their worth in protecting children from dangerous, sometimes deadly illnesses. Experts say undermining trust or restricting access now could reopen the door to outbreaks that public health worked so hard to shut.

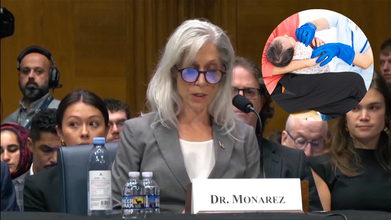

Hepatitis B Vaccination Timeline For Children Under Review Without Scientific Data, Says Former CDC Director Susan Monarez

Credits: Canva and Reuters

The US childhood vaccination schedule has become the center of a heated debate and much attention is being drawn towards it after a Senate hearing revealed the possible changes to when critical shots like the hepatitis B vaccine are given. Susan Monarez, former director of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) at the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions hearing said that she was fired in August for refusing two demands by Health Secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr, which were: fire career agency officials and sign off vaccine recommendations without seeing any data.

“He said if I was unwilling to do both, I should resign,” she said. “I responded that I could not pre-approve recommendations without reviewing the evidence, and I had no basis to fire scientific experts.”

At stake is not just the timeline of immunization, but also health and safety of millions of children who rely on vaccines to protect them from life-threatening diseases.

“The concern is Robert F Kennedy [Jr.] is going to make America sicker again,” said Sen. Ed Markey, D-Mass. “They’re going to send us towards more disease, more death and more despair in our nation.”

Why Does Vaccine Schedule Matter?

The CDC, through its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), sets the recommended vaccine schedule for children. While not mandatory, these guidelines strongly influence what health insurers cover and how doctors across the country advise parents.

For decades, the schedule has ensured that children are vaccinated against highly contagious diseases at the ages when they are most vulnerable. Changes to this timeline are not simply administrative, they have direct consequences on whether children remain protected against illnesses that once caused widespread suffering and death.

Debate Around The Hepatitis B Vaccine

One of the most debated issues that has risen is the hepatitis vaccine. It is from 1991 that the CDC recommended that babies must receive the first dose within 24 hours of birth, followed by additional doses at one month and between six to eighteen months.

This timing is not arbitrary. Hepatitis B is a viral infection that attacks the liver and can lead to cirrhosis, cancer, and lifelong health complications. Critically, the risk of developing chronic hepatitis B depends on the age at which a person is infected. Babies infected at birth have up to a 90% chance of developing chronic infection. Adults, by comparison, have only about a 5% chance.

Because many mothers are unaware they carry the virus, the birth dose serves as a crucial safeguard. It blocks transmission at the earliest stage, preventing lifelong illness and premature deaths.

So, What Could Change?

Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La., the committee’s chair, asked Monarez if Kennedy had told her he was going to change the childhood vaccination schedule. “He said that the childhood vaccine schedule would be changing starting in September, and I needed to be on board with it,” Monarez said.

What is being proposed contradicts the CDC recommendation of hepatitis shot being the first one for a child to receive within 24 hours of being born. Testimony at the Senate hearing suggested that the vaccine schedule could be revised to delay the first dose of the hepatitis B shot until age 4. Former CDC officials raised alarms that this proposal was not based on scientific data but rather political direction.

If implemented, such a shift would mean babies could go unprotected during the period when they are most at risk of contracting hepatitis B from their mothers or close contacts. Experts warned this would undo decades of progress in reducing infant infections, from 20,000 cases annually before 1991 to fewer than 20 per year today.

Risks of Delaying Vaccination

Delaying hepatitis B vaccination could open the door to a resurgence of preventable infections. Even if mothers are screened during pregnancy, screening isn’t perfect, and some may acquire the infection late in pregnancy or go undiagnosed. Without the immediate protection of the birth dose, babies would be vulnerable.

Moreover, shifting vaccines later in childhood carries another risk: missed doses. Studies show that adherence to vaccines is highest in infancy, when routine well-baby visits are frequent. Delaying could mean some children never get fully vaccinated at all.

The consequences are not minor. Untreated hepatitis B leads to chronic infection in most infants, setting them on a path toward liver damage, cirrhosis, and cancer later in life.

Concerns for Childhood Immunization

The hepatitis B vaccine isn’t the only one under review. The same advisory panel is expected to revisit recommendations for measles, chickenpox, and the updated COVID-19 shot.

Also Read: US Health Officials To Examine Covid Vaccine Effects In Pregnant Women And Kids

Critics worry that altering the established childhood schedule without thorough scientific review could destabilize public trust and increase preventable outbreaks.

The controversy comes at a time when confidence in public health agencies is already slipping. According to a recent KFF poll, trust in the CDC dropped from 63% in 2023 to 57% in 2025. Changes seen as politically motivated, rather than evidence-driven, could erode that trust even further.

Why Science-Based Decisions Are Essential

Experts stress that vaccination decisions should be grounded in data, not politics. The success of public health in the U.S., from reducing measles deaths to nearly eliminating mother-to-child hepatitis B transmission—has hinged on science-led policymaking.

Sen. Bill Cassidy, a gastroenterologist, reminded lawmakers that the hepatitis B vaccine transformed infant health in America: “Before 1991, as many as 20,000 babies were infected with hepatitis B each year. Now, fewer than 20 babies annually get the virus from their mother.”

Such achievements highlight the life-saving role of evidence-based vaccination. Undoing or weakening these protections without compelling scientific justification risks reversing decades of progress.

What Comes Next?

The ACIP meeting will be pivotal in determining the future of the childhood vaccine schedule. If changes are recommended, they could reshape how millions of American children are immunized. However, for many experts, the principle remains clear: any adjustments must be backed by rigorous data and public health expertise.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited