- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

With Chemicals 13,000X Sweeter Than Sugar, What Are The Toxic Risks Of ‘flavoured lies’ In Teen Vaping Products?

Credits: Canva

From sleek devices masquerading as highlighters to flavor clouds drifting down school hallways, vaping has burst into a global phenomenon, particularly among teens. Although e-cigarettes were first pitched as a "healthier" alternative to smoking, recent research unearths a disturbing concoction of chemicals lurking beneath those saccharine-tasting plumes. A few are 13,000 times sweeter than sugar. Others? Acutely poisonous. With the increasing popularity of these artificial mixtures, we might be at the beginning of a new epidemic of public health one conceived by "flavoured lies.

Vaping devices currently reign supreme in the nicotine market, with more than 4.5 million constant consumers in the UK alone and countless more internationally. For teenagers, flavored disposable e-cigarettes such as "Blue Razz Ice" or "Killer Kustard" are the most common gateway. In the United States, according to a 2024 federal survey, 5.9% of middle-school and high-school students consume e-cigarettes, with the majority using flavored products.

This popularity is not by chance. The fruit, dessert, and sweet tastes cover up nicotine's bitterness and provide a sensory experience that simulates candy, soda, or gum. Some products feature artificial sweeteners such as neotame, a 7,000–13,000-fold sweeter compound than sugar. Neotame is safe for food use according to the FDA just not for inhaling. The effects of inhaling such a potent compound into sensitive lung tissue are unknown, but it's now available in almost every leading unregulated disposable vape brand.

Flavored Vape Fueling Future Diseases?

A new study in JAMA tested 11 of the top-selling disposable e-vape brands—Elf Bar, Breeze, and Mr. Fog among them—and detected neotame in each and every one of them. What's more, the sweeteners were found even in vapes labeled "zero nicotine" or those with analogs, providing them with an even wider, youth appeal.

Scientists employed AI neural networks to model what occurs with the 180 flavor chemicals known when e-liquids are exposed to heat within a vape. The outcome? Alarming.

High temperatures cause dozens of new, toxic substances to emerge—most of which aren't even included in any label. These include:

- 127 "acutely toxic" substances

- 153 "health hazards"

- 225 "irritants

These byproducts contain volatile carbonyls (VCs), a family of chemicals that have been shown to destroy the lungs and cause cancer. These were most prevalent in the fruit- and dessert-flavored versions the same versions that control youth tastes.

Though the FDA has approved just 34 e-cigarettes, all restricted to menthol or tobacco flavors, the other 86% of the U.S. vaping market contains technically illegal flavored products yet widely dispensed at convenience stores and gas stations. They are largely made in China, where flavored vapes were outlawed on the domestic market in 2022, pushing exports into overseas markets such as the United States.

The Supreme Court recently upheld the FDA's refusal to approve flavored vape applications on the grounds of their irresistible attraction to young consumers. But in reality, enforcement is still fragmented and non-functional, with illegal, flavored vapes falling through the cracks and into the backpacks of children.

Why is it Particularly Dangerous for Teenagers?

The adolescent brain is particularly vulnerable to nicotine's impact, and specialists say that early exposure through vaping can have profound and long-lasting effects. Nicotine has been shown to modify the formation of neural pathways in teenagers, raising the likelihood of long-term dependence, diminishing cognitive ability and attention span, and even leading to mood disorders. There is also increasing worry that vaping is a gateway, that it's getting young people to move on to traditional smoking or to other drugs. But the threat is more than nicotine. Numerous youths who have never smoked are now regularly breathing in a mix of up to 180 chemical flavorings found in flavored vapes. These e-liquids include a combination of more than 180 flavoring chemicals, some of which were initially intended for consumption not inhalation.

When heated, they can transform into entirely new compounds, the health impacts of which are not yet fully understood. Unlike tobacco, which took decades to definitively link to lung cancer and heart disease, vaping is introducing unregulated, high-temperature chemicals into young lungs, creating a public health challenge whose full effects may only be known years from now. Most of the 180 flavor chemicals found in e-liquids are derived from the food industry. There, they are safe to consume. But inhale and heat them? A whole other story.

Chemicals such as diacetyl, which is characterized by its "buttery" taste, have already been associated with popcorn lung a serious but unusual type of lung disease. Researchers now fear that a series of long-term diseases will become reality in the next few decades as a result of extended exposure to vaping, particularly among individuals who started smoking e-cigarettes in their teens.

The inconsistency of vaping products also adds to the confusion. Variations in the design of batteries, temperature control, and e-liquids ensure that no two puffs are identical, so the health concerns become even more uncertain.

The charm of sweet, dessert-like vapes might seem innocent even exciting to some average teen but at the back of those flavors are chemicals never meant to be inhaled, and which could lead to health issues years later.

2 Infants Died Of Whooping Cough In Kentucky, Health Officials Report; Who Should Get A Booster Shot?

Two babies in Kentucky have lost their lives to pertussis, also known as whooping cough, as recently reported by the Kentucky Department for Public Health. These deaths, the first pertussis-related since 2018, have refocused attention on a resurging danger once thought largely brought under control in America- vaccine-preventable illnesses.

With over 10,000 cases reported across the country in the first six months of 2025, close to twice as many as the same six months a year ago public health officials are warning an alarm. The epidemic, which tracks with trends in other diseases like measles, coincides with declining childhood vaccination rates, anti-vaccination sentiment, and pandemic-period interruptions of routine vaccination activities.

Whooping cough is a very contagious respiratory infection that is brought on by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis, originally described in 1906 by French scientists. Nevertheless, centuries ago, there were mentions of the illness—its earliest probable epidemic was seen in Paris in 1578.

The disease is notorious for its intense, hacking cough that is followed by a piercingly high-pitched "whoop" upon inhalation. In newborns, particularly those too young to be vaccinated, pertussis may cause lethal complications such as pneumonia, seizures, and respiratory distress. Some doctors call it "the 100-day cough" because its duration lasts for many weeks or even months.

According to the World Health Organization, pertussis still causes approximately 160,700 deaths annually in children under the age of five worldwide, a statistic that highlights the ongoing global burden of the disease, especially in settings with limited vaccine coverage.

The two infants who perished in Kentucky in the last six months were not vaccinated, and neither were their mothers while pregnant. These events highlight a key gap in protection that maternal vaccination seeks to close. Babies under 6 weeks are too young to get their first dose of pertussis vaccine, and so remain extremely exposed early in life.

Third-trimester maternal immunization allows for the passing on of protective antibodies to the newborn, protecting them until they are of age to start their own vaccine regimen. Without the added layer of protection, there is a marked increase in risk of severe illness or mortality.

Through June 2025, the U.S. has reported a minimum of 8,485 confirmed cases of pertussis, already passing the 4,266 cases reported for the same period in 2024. For 2024, as reported by the CDC, a combined total of 35,435 cases were reported—more than five times that of 2023 and close to twice that of 2019, the final year before the pandemic.

Kentucky alone has reported 247 cases of pertussis through 2025, after reporting 543 cases in 2024—the largest number in the state since 2012. Across the country, from October 2024 through April 2025, four deaths from pertussis have been reported: two infants, one school-age child, and one adult.

Why Are Whooping Cough Cases Increasing Again?

The return of pertussis in the United States is being fueled by a mix of related factors. One major cause is the cyclical pattern of the disease, since pertussis has epidemic patterns with episodes peaking every two to five years. Although such peaks are anticipated, experts note that the current peak is more severe compared to what is normally seen during normal peaks. Post-pandemic immunity gap is also a crucial factor. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic that occurred during 2020 and 2022, pertussis rates decreased significantly because of widespread public health interventions like masking, physical distancing, and closing schools. Since those measures are no longer in effect, numerous persons including children who were left unvaccinated or were missed during their periodic vaccinations since then are now at increased risk for infection. Adding to this problem is the decrease in vaccination coverage, driven by increased misinformation, increased skepticism about the vaccine, and interruptions in access to health care. That decline in immunization, especially in infants and pregnant women, is one of the most urgent priorities driving the national epidemic of pertussis.

How Effective Are Vaccines Against Pertussis?

The pertussis vaccine itself has changed dramatically over the years since it was first introduced in the U.S. in 1914.

Today's acellular form—DTaP for infants and children and Tdap for teens and adults—was introduced in the 1990s as a way to reduce side effects like seizures and high fevers that were caused by the older whole-cell vaccine. Although the acellular vaccine offers robust protection initially, the immunity fades with time. During the first year after completion of the five-dose course of childhood pertussis vaccination, some 98% of children are protected against pertussis.

By the fifth year after the last dose, however, that immunity declines to roughly 65%. This drop highlights the necessity of booster shots in young adulthood and adolescence to ensure sustained protection. While immunity from the current vaccine is not long-term, it still represents the best weapon against severe disease, complications, and mortality. The unvaccinated are 13 times more likely to develop pertussis compared to their vaccinated counterparts, and they have much greater risks of being hospitalized or killed by the disease.

Who Should Be Vaccinated, and When?

The CDC and other top public health organizations suggest:

Infants: Shots at 2, 4, and 6 months, with boosters at 15 months and 4 years.

Adolescents: A Tdap booster dose at 11 or 12 years.

Adults: One Tdap booster in adulthood, with re-vaccination every 10 years.

Pregnant Women: One dose of Tdap between weeks 27–36 of every pregnancy to confer immunity to the newborn through passive antibody transfer.

Local health departments might even suggest extra boosters for people who reside in outbreak-facilitating areas particularly on the West Coast, where states such as California, Washington, and Oregon have seen high case totals this year.

How Can You Protect Yourself and Your Family?

The increase in pertussis cases—and its disastrous effect on babies—underscores the necessity of public education, uniform messaging by health workers, and availability of immunization services. Parents and caregivers should be motivated to keep their own and children's vaccination schedules up to date, especially in communities where disease outbreaks are reported.

Clinicians have a key role in advising maternal immunization and informing families about the signs of whooping cough, which is likely to be confused with the common cold at its initial onset.

Is It The Next Pandemic? New COVID-19 Like Virus From China Raises Global Health Concerns

Credits: Canva

A new strain of coronavirus discovered in China, known as HKU5-CoV-2, could be only a few mutations away from triggering the next deadly pandemic, say American scientists. The virus was identified by researchers at Washington State University (WSU). The researchers have said that it shares close genetic similarities with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)—a highly lethal virus that kills nearly a third of those it infects. The findings have raised serious concern in the global scientific community.

A Close Cousin of MERS

MERS, which emerged in 2012 and has caused sporadic outbreaks primarily in the Arabian Peninsula, is known for its severe respiratory symptoms and high mortality rate. HKU5-CoV-2, the new virus under scrutiny, belongs to the merbecovirus family—a group of viruses that includes MERS. While not yet known to infect humans, scientists warn that a minor genetic mutation could allow it to do so, raising the possibility of another global health emergency similar to COVID-19.

“This virus may be only a small step away from being able to spill over into humans,” said Professor Michael Letko, a virologist at WSU and co-lead author of the study.

What the Study Found

The study focused on how HKU5-CoV-2 interacts with human cells. Originally found in bats, this virus was identified by Chinese scientists from the same lab some speculate may have been linked to the origins of COVID-19. In the new study, WSU researchers examined the virus's ability to bind to human ACE2 receptors—proteins located in the nose, mouth, and throat that serve as entry points for coronaviruses.

Using advanced cryo-electron microscopy, researchers captured detailed images of the virus's spike protein, revealing that key segments of the spike often remain “closed.” This closed structure typically makes infection harder—but not impossible.

The team observed that while human cells generally resist infection from HKU5-CoV-2, the virus could latch onto human ACE2 receptors if specific mutations occur. These mutations could enable the virus to enter human cells more effectively, increasing its potential to cause disease.

Risks from Intermediate Animal Hosts

Another concern is the possibility of the virus mutating in intermediate animal hosts, such as mink or civets, before jumping to humans. Such transmission chains have been seen in other coronavirus outbreaks, including both SARS and MERS. If HKU5-CoV-2 were to infect these animals, it might gain the ability to infect humans more efficiently, scientists warn.

“Viruses that are already this close to MERS in structure and function are definitely worth monitoring,” Letko emphasized.

Lineage 2 and Immediate Threats

Earlier in 2025, researchers in Wuhan reported that one strain of HKU5—Lineage 2—already shows the ability to bind to human ACE2 receptors without further mutation. This suggests that some forms of the virus may already be equipped to infect humans.

Building on that discovery, the WSU team expanded their research to look at the entire merbecovirus family. Their findings indicate that several other strains, not just Lineage 2, may only require minimal changes to become capable of infecting humans.

Vigilance Needed

As the world continues to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists stress the importance of ongoing surveillance and pre-emptive research into emerging viruses like HKU5-CoV-2. Even if they cannot yet infect humans, understanding their structure and behavior is crucial for early intervention.

"The lesson from COVID-19 is clear—we cannot afford to ignore even small viral threats," Letko concluded.

Anthrax Outbreak at Thai Tourist Hotspot: 1 Dead, 4 Hospitalized

Credits: Canva

An anthrax outbreak has hit Thailand's top tourist areas and has killed man, while four have been hospitalized, confirmed health officials.

As per the authorities, they are now racing against the time to trace the source of this dangerous livestock disease, which has a highly infectious bacterial infection.

What Is Anthrax?

As per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), anthrax is a serious disease usually caused by Bacillus anthracis bacteria. The bacteria is found in soil around the world and commonly affect livestock and wild animals. People who usually get sick with anthrax may have come in contact with infected animals or contaminated animal products.

People can breathe in anthrax spores, eat food or drink water contaminated with spores or get spores in a cut or scrape in the skin.

What Is Happening In Thailand?

According to Thai authorities, the 53-year-old victim from Mukdahan, near the Laos border, died after showing symptoms consistent with anthrax. He developed a dark lesion on his hand just days after slaughtering a cow last month. Soon after, he experienced swollen lymph nodes, dizziness, and seizures. Although he sought treatment at a local hospital, he died before doctors could intervene effectively. Laboratory tests later confirmed that he had contracted anthrax, local media reported.

Early investigations suggest the man was exposed to anthrax after a cow was slaughtered during a religious ceremony. The meat was shared and consumed within the village, and four other people from the same province later fell ill—each case linked to infected cattle or contaminated meat.

Doctors say three of the infected individuals are close to full recovery, though a fifth case has now been reported. In response, officials have quarantined all animals—including vaccinated cattle—within a five-kilometre radius of the outbreak. Tests on meat, knives, chopping boards, and soil came back positive for anthrax spores. Authorities are currently monitoring over 600 people who may have been exposed to infected livestock or meat.

As per the World Health Organization (WHO), local authorities have “identified and provided post-exposure prophylaxis to all high-risk contacts” and “implemented a robust set of control measures.” They added: “Currently, due to the robust public health measures implemented by Thailand, the risk of international disease spreading through animal movement remains low.”

What Are The Types Of Anthrax?

Cutaneous Anthrax

Cutaneous anthrax is the most common—and least dangerous—form of the infection. It occurs when anthrax spores enter the body through a cut, scrape, or open wound on the skin. This often happens while handling infected animals or contaminated animal products like wool, hides, or hair. The infection typically appears on the head, neck, forearms, or hands as a sore that turns into a black-centered ulcer.

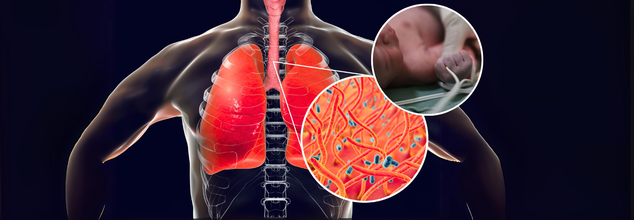

Inhalation Anthrax

This is the most severe and life-threatening type of anthrax. It happens when someone breathes in airborne spores, often in environments like wool mills, slaughterhouses, or tanneries where infected animal products may be present. The disease usually begins in the lymph nodes of the chest before spreading rapidly throughout the body.

Gastrointestinal Anthrax

Gastrointestinal anthrax occurs when someone eats raw or undercooked meat from an infected animal. Although rare—especially in the United States—it can affect the throat, esophagus, stomach, and intestines. Symptoms vary but can include sore throat, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and severe digestive issues.

Welder’s Anthrax

Recently identified, this rare form of anthrax has been found in welders and metalworkers. It leads to severe pneumonia and can be fatal. Workers in metal industries who experience sudden fever, cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, or coughing up blood should seek medical attention immediately.

Injection Anthrax

This type has been reported among heroin-injecting drug users in northern Europe. It occurs when spores are introduced deep under the skin or into the muscle through contaminated drugs. Though similar to cutaneous anthrax, it causes more severe infections in deeper tissues. It has not yet been reported in the United States.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited