- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Centenarian Blood Reveal What Might Be The Secret To Living Past 100- 3 Biomarkers Of Longevity

Credits: Canva

Living past 100 isn’t just a milestone—it’s a biological mystery. For centuries, philosophers like Plato and Aristotle have speculated about aging, but only now, with modern science, are we beginning to decode the factors that separate the exceptionally long-lived from the rest of us.

And while lifestyle advice like “eat healthy” or “exercise regularly” still holds, new evidence suggests your blood might already be telling the story of how long you'll live decades before you reach old age.

A new study out of Sweden, published in GeroScience, has analyzed blood samples from over 44,000 people and tracked their health for more than three decades. The results? Those who lived past 100 shared subtle but consistent differences in certain biomarkers, particularly those tied to metabolism, inflammation, kidney and liver function, and nutrition

How Are Centenarians Biologically Distinct?

Centenarians (people who live to 100 or beyond) used to be statistical outliers. Today, they're one of the fastest-growing age groups in the world, doubling roughly every ten years since the 1970s. This demographic shift is forcing researchers to examine what exactly allows some people to not only live longer, but to live well into their 90s and beyond—often with fewer chronic conditions.

The Swedish study used data from the Amoris cohort, tracking people aged 64–99 for up to 35 years. Out of 44,000 participants, 1,224 (2.7%) lived to 100, and interestingly, 85% of them were women.

Rather than focus on anecdotal habits or isolated lifestyle factors, the researchers went straight to the bloodstream—measuring 12 key blood-based biomarkers that reflect various physiological processes including inflammation, metabolism, kidney and liver health, and nutritional status.

Subtle Signs That Set Centenarians Apart

When comparing those who lived to 100 with those who didn’t, the differences weren’t necessarily dramatic—but they were meaningful. One of the findings- centenarians tended to have lower levels of glucose, creatinine, and uric acid from their 60s onward.

While the median biomarker values weren’t always drastically different between groups, what stood out was that centenarians rarely had extremely high or low values. This biological "moderation" suggests that extreme metabolic fluctuations earlier in life may correlate with lower chances of exceptional longevity. For instance:

- Very few centenarians had glucose levels above 6.5 mmol/L.

- Likewise, only a small fraction had creatinine levels above 125 µmol/L.

Even uric acid often overlooked had a surprisingly predictive role. People with the lowest uric acid levels had a 4% chance of reaching 100, compared to just 1.5% among those with the highest levels.

What Exactly Biomarkers That Help You Live Longer?

The biomarkers measured in the study covered a wide range of physiological systems:

Inflammation: Uric acid

Metabolism: Total cholesterol, glucose

Liver function: Alanine aminotransferase (Alat), aspartate aminotransferase (Asat), albumin, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase (Alp), lactate dehydrogenase (LD)

Kidney function: Creatinine

Nutrition and anemia: Iron, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), and albumin

What’s striking is that 10 out of the 12 markers were linked to the likelihood of becoming a centenarian, even after adjusting for age, sex, and disease burden.

Albumin and Alat were the only two that didn’t show a significant association—but the rest provided strong clues that biological aging begins much earlier than we think, and that it leaves a footprint in our blood.

Is There a Connection Between Nutrition, Metabolic Health and Longevity?

Although this study didn’t isolate specific lifestyle factors, the associations are suggestive. The fact that metabolic and nutritional biomarkers—like glucose, cholesterol, and iron, correlated with longer life spans aligns with broader research on the importance of diet, alcohol moderation, and weight stability in aging.

It's worth noting that both low and high levels of certain markers were associated with poorer outcomes, reinforcing the idea that optimal, balanced ranges not extremes may be most important when it comes to aging well.

This insight has practical implications: monitoring your metabolic and organ health in your 60s and beyond may provide an early-warning system for how your aging trajectory is shaping up.

Genes vs. Lifestyle: How Much Control Do We Really Have?

This study doesn't confirm whether genes or behavior drive the biomarker differences—it only shows that those who lived longest had more favorable profiles. According to Karin Modig, Associate Professor of Epidemiology at the Karolinska Institutet and lead author of the study, chance probably plays a role, but so do genes and lifestyle choices.

In other words, some people may be genetically predisposed to age more slowly, but even among those individuals, metabolic moderation and good organ function seem to be common themes.

You don't need to chase some mythical "perfect" blood profile but that small, cumulative differences in biological function across decades may matter more than we thought.

Paying attention to your glucose, creatinine, and uric acid levels as you age could help you catch red flags early. Liver and kidney markers, often underappreciated, may hold secrets to long-term health. Nutrition appears to play a much more central role in aging than many assume.

None of these factors guarantees you’ll live to 100—but they do suggest pathways worth preserving, monitoring, and optimizing.

This is the largest, longest-running study of its kind, and it delivers something few others have: longitudinal data on real people, across decades, tied to actual life outcomes.

Rather than rely on speculative theories or small anecdotal samples, the findings here provide a roadmap for future aging research, one that blends genetics, biology, lifestyle, and public health.

As the global population continues to gray, understanding how to extend not just lifespan but healthspan—the years of life spent in good health—will be critical. And studies like this bring us one step closer to unlocking the biology of exceptional aging.

Doctor Explains Why Weight Loss Drugs Like Ozempic Are Truly A Medical Breakthrough

Credits: iStock

Ozempic, Mounjaro, Wegovy, and many more such popular weight loss drugs are now making headlines. They are also dominating social media, dinner table conversation and many more. But, is Ozempic truly a medical breakthrough, a miracle drug? Dr Shubham Vatsya, a gastroenterologist, and hepatologist at Fortis Vasant Kunj explains how did this drug change the weight loss struggle that many people face.

Why Is GLP-1 Drug A Medical Breakthrough?

Dr Vatsya explains that it took 20 years of research for scientists to come up with these medicines. This drug underwent proper lengthy trials, and have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), "which is not obtained by giving any bribe".

Also Read: Fact Check: Is Weight Lifting Safe for Teens? An Expert Explains the Risks and Safer Alternatives

He also noted that when a person is not able to lose weight, Ozempic and drugs alike give a "head start" to them, along with a hope.

Talking about side effects, he says that every drug has its side effects, this is where a doctor's role comes in.

"Now, the person who is not able to lose weight, if you tell him 'you hit 100 kg bench press', he will break his shoulder. He needs a kickstart somewhere. This is what weight loss drugs allow," he says.

He also points out that the scientists who made GLP-1 agonists got a Nobel Prize, which "cannot be a scam". This is what makes weight loss drugs truly different.

What Are GLP-1 Drugs?

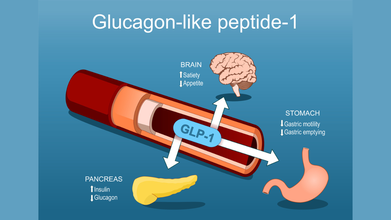

GLP-1 Drugs stand for Glucagon-like peptide 1, a naturally occurring hormones that helps regulate blood sugar and appetite after eating. It was first identified almost 50 years ago and scientists have since uncovered its role in type 2 diabetes.

Almost two decades of research went behind it that led to the development of GLP-1 agonists. It was in 2005, when the first GLP-1 medication, exenatide was approved.

Read: Could You Become Addicted To Your Weight Loss Drugs?

These medications have three main functions:

- Stimulating the pancreas to release insulin

- Slow the transit of food in the stomach to help people feel fuller for longer after a meal

- Act on areas of the brain that regulates hunger and fullness, leading to smaller portion sizes and reducing cravings

Popular drugs like Ozempic and Wgovy, which have semaglutide, which is a GLP-1 receptor agonist, or tirzepatide found in Zepbound and Mounjaro are FDA-approved for type 2 diabetes and weight loss.

These drugs work by binding GLP-1 receptors in the body, which in return increase insulin production in response to food intake and suppress glucagon, a hormones that raises blood sugar.

Also Read: How Weight Loss Drugs Change Ones Relationship With Food?

Are The Popular Weight Loss Drugs Addictive?

There is currently no data suggesting that GLP-1 medications cause physiological addiction. Interestingly, some research suggests they may even reduce cravings related to alcohol or opioid use. That directly contradicts the idea that these drugs hijack the brain’s reward system in a traditional addictive way.

Still, wanting or feeling unable to stop a medication because of fear of weight regain or loss of control is very real. That experience should not be dismissed, even if it is not addiction in the clinical sense.

These medications are meant to support long-term habit change, not replace it. Nutrition, movement, sleep, and a healthier relationship with food are meant to develop alongside the medication. When people reach their goal weight, doctors may suggest tapering the dose slowly or moving to a lower maintenance schedule rather than stopping abruptly.

Stopping suddenly can make hunger feel overwhelming. A gradual transition allows the body and mind time to adjust. Some people do successfully maintain weight loss without the medication, but it usually requires strong lifestyle foundations first.

Going Through Cough And Flu? NHS Issues Urgent Cough Syrup Warning

Credits: Canva

As cough and flu season sweeps across the UK, health expert Dr Xand shared crucial guidance during today’s episode of BBC Morning Live (Jan 19) for anyone struggling with a stubborn cough. The discussion focused on coughs and colds, highlighting new research showing that human rhinovirus, a common cause of cold, can also trigger pneumonia in adults.

Flu Season In UK: Warning Signs To Watch For

Speaking with presenters Helen Skelton and Gethin Jones, as per Mirror, Dr Xand, a specialist in public and global health, explained which symptoms indicate a cough should not be ignored. He noted that a persistent cough is one of the key signs of pneumonia.

Gethin asked, "A cough happens with many illnesses, so when should someone really worry?" Dr Xand replied, "This is a big question, and plenty of people at home might be thinking, 'Is this serious?' because coughs can linger for a long time."

He continued: "Viruses like respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) can cause what’s known as the 'hundred-day cough,' and people can be coughing for weeks wondering what’s going on."

Dr Xand advised viewers to follow the NHS guidelines for coughs, saying, "The NHS recommends consulting your doctor if a cough persists for over three weeks. Many coughs last three to four weeks, and you’ll usually notice if they’re improving. Right now, the most common cause is a virus."

Dr Xand’s Cough Syrup Alert

Addressing people from home about cough syrups, Dr Xand highlighted the latest NHS guidance. He suggested trying more natural remedies, which can be just as effective. "The NHS does not actually recommend cough syrup," he explained. "It advises hot lemon with honey instead."

The official NHS website confirms that "hot lemon with honey has a similar effect to cough medicines." This simple remedy can soothe the throat, calm irritation, and reduce the cough reflex. Some studies even suggest it works as effectively as certain over-the-counter medicines, particularly for children over one year old. However, it’s important to note that it doesn’t treat the underlying illness.

What Do Cough Syrup Studies Show?

Research shows that most over-the-counter cough medicines offer minimal benefits. Studies, including those from the Cochrane Collaboration, reveal that they perform little better than a placebo for short-term cough relief in both adults and children.

While these syrups may temporarily ease throat irritation or provide a sense of relief, ingredients such as dextromethorphan and guaifenesin often do no better than sugar pills. Much of the perceived benefit comes from the placebo effect or the body’s natural recovery.

Instead, simpler measures like honey, staying hydrated, and using painkillers such as paracetamol or ibuprofen are often more effective. Most coughs caused by colds simply need time to resolve.

Cough Syrup: Red Flags To Watch For

Dr Xand shared the warning signs people should be aware of. "There are several red flags worth noting. High fever, chills, or unexplained shortness of breath are all reasons to see a doctor immediately. You should be able to breathe normally, and if you can’t, that’s a concern."

He added, "Any chest pain with a cough, very thick mucus, or extreme fatigue are also serious signs. More severe warning signals include trouble breathing, bluish lips or fingertips, confusion, mental changes, prolonged high fever, and a rapid heart rate."

"It’s crucial to act quickly," Dr Xand continued. "I’ve seen cases in my own family where someone went from a mild cough to being extremely unwell in just a day. Sudden deterioration can be life-threatening, so early medical help is essential."

Pneumonia Can Be Subtle but Serious

Dr Xand emphasized, "Pneumonia can sometimes develop quietly. It isn’t always dramatic, but it can be fatal. That’s why it’s so important to monitor symptoms and seek medical help promptly if things are getting worse."

Vitamin B12 And D3 Deficiencies Could Lead To Serious Health Issues, Experts Warn

Credits: AI Generated

Vitamin deficiencies are often brushed aside as minor nutritional gaps. Many people assume they can be fixed later or ignored until something feels seriously wrong. According to Dr Prabhat Ranjan Sinha, Senior Consultant, Internal Medicine at Aakash Healthcare, this casual attitude can be risky, especially when it comes to Vitamin D3 and Vitamin B12. Both nutrients play a central role in bone strength, nerve function, immunity, and energy levels. When their levels drop, the damage may build quietly and surface only when daily life starts to feel difficult.

Vitamin D3 and Vitamin B12 are essential for overall wellbeing. Their deficiency may not cause obvious symptoms at first, but over time they can affect how the body functions, how often a person falls sick, and how energetic or mentally sharp they feel.

Vitamin B12 And D3 Deficiencies: The Sunshine Vitamin And Why It Matters

Vitamin D3, often called the sunshine vitamin, is produced by the body when skin is exposed to sunlight. Along with calcium, it helps maintain strong bones and reduces the risk of fractures. Low levels of Vitamin D3 can weaken muscles, increase the risk of falls, and raise the chances of bone disorders such as osteoporosis. In children, severe deficiency can lead to rickets, a condition that affects normal bone growth.

Dr Sinha explains that Vitamin D3 does more than support bone health. It also plays a key role in immune function. People with low levels may fall sick more often and take longer to recover from infections. Research has also linked deficiency to higher levels of inflammation in the body.

Despite living in a country with abundant sunlight, Vitamin D3 deficiency is widespread. Urban lifestyles keep many people indoors for long hours. Regular use of sunscreen, limited outdoor activity, and aging all reduce the body’s ability to produce and absorb this vitamin. Diet alone rarely provides enough Vitamin D3, which is why deficiency remains common even among people who eat well.

Vitamin B12 And Its Silent Impact

Vitamin B12 is equally important but often overlooked. It is essential for nerve health, brain function, and the production of healthy red blood cells. Unlike some deficiencies that show early warning signs, B12 deficiency tends to develop slowly. Its symptoms are often mistaken for stress, aging, or routine fatigue.

Low Vitamin B12 levels can cause weakness, persistent tiredness, tingling or numbness in the hands and feet, memory problems, mood changes, and difficulty concentrating. Over time, untreated deficiency can lead to nerve damage and anemia.

Certain groups are at higher risk. Vegetarians and vegans often do not get enough B12 because it is mainly found in animal-based foods. Older adults may struggle to absorb B12 due to reduced stomach acid. People with digestive disorders and those taking long-term acid-reducing medications are also more vulnerable.

Why These Deficiencies Are Missed?

One of the biggest challenges with Vitamin D3 and B12 deficiencies is that their symptoms overlap with many common health complaints. Ongoing fatigue, joint pain, low mood, or frequent illness are often blamed on work stress, poor sleep, or lifestyle habits. As a result, people delay medical advice until symptoms start interfering with everyday life.

Dr Sinha notes that this delay can make recovery slower and complications more likely.

Vitamin B12 And D3 Deficiencies Diagnosis And Timely Care

Simple blood tests can accurately detect Vitamin D3 and B12 deficiencies. However, many people only get tested once symptoms become severe. Early diagnosis allows for timely treatment, which may include supplements, dietary changes, and lifestyle adjustments under medical guidance.

Addressing these deficiencies early is one of the simplest ways to protect long-term health. Adequate sunlight exposure, balanced nutrition, and routine screening can help maintain healthy levels. Taking Vitamin D3 and B12 deficiencies seriously is a small step that can prevent lasting health problems and support healthier aging.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited