- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

How To Curb Excessive Melanin Production?

Melanin (Credit: Canva)

Have you ever wondered how your skin gets its colour? Well, it is because of a pigment called Melanin, which is naturally present in all human beings. This pigment not only gives colour to your skin but also to your hair and eyes. In addendum, it also protects your skin from ultraviolet (UV) rays. However, when melanin is produced in excess, it results in a darker complexion.

But What Are Reasons Behind Excessive Melanin Production?

Reasons for a excessive production of melanin in your skin could be varied. Over exposure to sunlight could be one of the reasons, other could be genetics. Notably, in some cases, melanin production may be concentrated in some parts of the body, making skin in those areas darker than others. This is known as hyperpigmentation.Now, there are various beliefs about the cure of this. While some people try limiting their exposure to the sun, assuming that it will go by itself. Others try excessive scrubbing to get rid of this pigmentation. Many try dermatological products.

Dr Sachith Abraham, consultant of dermatology, at Manipal Hospital, says overproduction of Melanin can be avoided by regularly applying sunscreen with at least 50 SPF. Additionally, you can wear wide-brimmed hats for sun protection. He also emphasised having a well-defined and strict skincare routine. To lighten the hyperpigmented skin, he suggested trying the liquorice extract to remove excess pigment. Another tip is to use the milk extracts as it has lactic acid.

According to Dr Sachith, various topical cream like kojic acid, arbutin, liquorice extract and topical vitamin C and retinol can remove pigmentation on the skin. Other treatments include chemical peels. Other treatments like chemical peels and lasers can also be done.

Can excessive production of melanin harm you?

While overproduction of melanin does not lead to any serious life threats, certain conditions like lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) can be associated with it. Notably, in Addison's disease, a person's adrenal gland is affected and therefore, it can lead to hyperpigmentation.

The Age You Get Your First Period At Can Help Identify Long-Term Health Risks

(Credit-Canva)

The first period is a significant moment in the life of a young girl, however, when it happens, the age, plays a much more important role than we realize. National Health Services UK explains that periods can start as early as 8, however the average age is about 12.

A new study showcased in the ENDO Annual Meeting 2025, Endocrine Society from Brazil has found that the age a woman gets her first period, also known as menarche, could provide important clues about her future health. The study shows that both starting your period very early or very late can lead to different health problems later in life.

Different Risks for Different Ages

The age a woman gets her first period (menarche) and the age she reaches menopause mark the beginning and end of her reproductive life. The study looked at data from over 7,600 women in Brazil. It found a link between the timing of menarche and long-term health risks.

Early Menarche

Women who got their first period before age 10 were more likely to have health issues like obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart problems. They also had a higher risk of reproductive issues like pre-eclampsia.

Late Menarche

Women who started their period after age 15 were less likely to be obese. However, they faced a greater risk of menstrual problems and some specific heart conditions.

What This Means for Women's Health

According to the study's author, Flávia Rezende Tinano, these findings confirm how the timing of puberty can affect a woman's health over many years. She explains that knowing when a woman had her first period can help doctors identify those who might be at a higher risk for certain diseases. This information can lead to more personalized health screenings and preventative care.

The study is one of the largest of its kind in a developing country. It provides valuable data for populations, like those in Latin America, that have been underrepresented in past research. The researchers believe that these findings highlight the need for early health education for young girls and women.

How Timing Reveals Health Risks For Women

A 2013 study published in the Adolescent Health Medicine and Therapeutics journal explained that the timing of these key events can provide important clues about her long-term health. Both very early and very late timing of menarche or menopause have been linked to a higher risk of health problems. Because of this, understanding the connection between these two events could help with preventing chronic diseases. Scientific studies from various fields, including biology, nutrition, and psychology, have looked at the relationship between menarche and menopause.

Early or Late Timing Matters: A woman's age at menarche and menopause is a key sign of her body's aging and how her ovaries are functioning.

Health Connections: Both starting periods very early or very late are linked to different health and social risks later in life.

While many studies have explored the link between menarche and menopause, the results have been mixed. Out of 36 studies reviewed, ten found a direct link, meaning an earlier first period was connected to an earlier menopause. Two studies found the opposite, and the rest found no connection at all. Researchers believe that many things affect the timing of these events, including:

- Hormones and environment

- Socioeconomic status

- Stress throughout life

- Body size and height

Have You Ever Felt Dizzy, Lightheaded When You Stand Up? Here's What It Means

Credits: Canva

Think about that fleeting moment when you get up after sitting or lying down—your head spins, your heart pounds, maybe you feel lightheaded or nauseated. If this scene has become all too familiar, you might be dealing with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome—POTS. It’s rare, but for the 1–3 million people in the U.S. who have it, it’s daily life. Now, a heart failure drug is showing real promise in taming the symptoms.

Ivabradine isn’t new—it’s been used for years to manage chronic heart failure, slowing the heart without dropping blood pressure. But a new pilot study, published in the Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology, suggests this drug might be a breakthrough for POTS patients. Researchers from UVA Health and Virginia Commonwealth University treated 10 young adults (average age 28, most of them women) with the drug. Normally, when these patients stood, their heart rates surged by around 40 beats per minute. After ivabradine? The spike shrank to only 15 bpm. And symptoms like faintness dropped by nearly 70%, chest pain by 66%—the difference wasn’t just physiological, it was life-changing.

Dr. Antonio Abbate from UVA Health called the findings compelling: cutting heart rate alone—without affecting blood pressure—appeared to break the chain of symptoms. “The inappropriate increase in heart rate is exactly why patients feel sick,” he said.

UVA Health Newsroom

What Is POTS?

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome may sound technical, but its components describe the experience: "postural" (related to posture), "orthostatic" (standing upright), "tachycardia" (a fast heart rate), and "syndrome" (a bundle of symptoms). When someone with POTS stands, their autonomic system fails to constrict blood vessels effectively. The result? Blood tanks into the legs, the heart overcompensates, and you get hit by symptoms: dizziness, pounding heart, fatigue, brain fog, chest discomfort, sweating, nausea—anything but ordinary.

This isn’t a heart-muscle issue or a brain problem: it’s more like a software glitch in how your body regulates itself. It often affects young women between 15 and 50 and can stem from triggers like infections, trauma, pregnancy, or autoimmune diseases.

The recent UVA pilot study isn’t standalone. Earlier research supports the same direction. A 2017 retrospective study of 49 patients—almost all women—found 88% saw palpitations improve and 76% felt less lightheaded, with heart rates dipping and no significant change in blood pressure.

Then a 2021 randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial—including 22 adults with hyperadrenergic POTS—took it further. The results showed substantial heart rate drops, improved physical and social quality of life, and even reduced norepinephrine levels (the stress hormone that tends to over-react upon standing). None of the participants developed dangerously low blood pressure.

And even earlier studies, including student-case reports and case series, all support the conclusion: ivabradine reduces heart rate without bringing blood pressure down—and that matters because traditional beta blockers can drop both, making some patients feel worse.

How Ivabradine Interrupts the Vicious Vagus Loop?

Here’s what researchers suspect is happening behind the scenes: when someone with POTS stands, the body overreacts with a surge of norepinephrine—our classic fight-or-flight hormone. The heart races, the brain kicks into panic mode, symptoms amplify, and the loop perpetuates itself. Ivabradine, by slowing the heart without altering blood pressure, effectively breaks that cycle at the source. Patients stop spinning, both literally and metaphorically.

What You Should Know POTS?

It's worth noting that these are still early results. The studies are relatively small, but statistically compelling. There's enough here, though, to encourage more formal trials—and for doctors and patients to take notice.

If POTS symptoms sound familiar—if you get faint when you stand, your heart races, and doctors struggle to pinpoint the cause—ivabradine may be a conversation worth having. It’s not a universal cure, but it’s different from other treatments. Rather than forcing blood vessels to tighten or increasing blood volume, it focuses squarely on the heart rate itself.

POTS has always been a misunderstood syndrome—a tricky physiological dance that leaves patients frustrated and clinicians unsure. But treating the pulse directly, instead of chasing blood pressure or fluid levels, looks like a game changer. Ivabradine isn’t a cure-all, but it's poised to offer relief where little existed before.

For anyone sick of dizzy spells, pounding hearts, or unexplained fatigue whenever they stand, it’s time to explore if this one medication could be the difference between feeling trapped and regaining control.

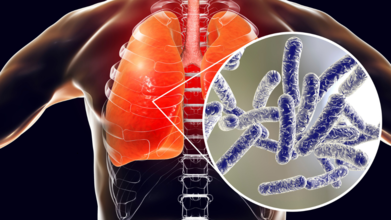

Unique COVID-19 Like Symptoms Of Legionnaires' Disease And How Long Does The Infection Last

Credits: Canva

Legionnaires’ disease, has so far killed 3, and infected around 60 people after the recent outbreak in Central Harlem in the New York City. It is a severe form of pneumonia caused by Legionella pneumophila, and is far more than just a respiratory infection.

Unlike typical bacterial pneumonias, Legionnaires’ disease is increasingly being recognized for its distinct symptoms, both during the acute illness and long after recovery.

Now, a landmark study from Switzerland aims to uncover whether Legionella infections lead to their own version of a “long COVID”-like syndrome, providing crucial insights into the post-acute impact of this underdiagnosed illness.

What Makes Legionnaires’ Disease Different?

Named after a deadly outbreak during an American Legion convention in Philadelphia in 1976, Legionnaires’ disease is spread primarily through contaminated aerosolized water, not person-to-person contact.

The bacteria thrive in warm, stagnant water found in air-conditioning cooling towers, plumbing systems in large buildings, hot tubs, fountains, and even ice machines.

While the respiratory symptoms may initially resemble other types of pneumonia, cough, fever, and shortness of breath, what sets Legionnaires’ disease apart is the constellation of extrapulmonary symptoms that often accompany it.

These include:

- Muscle aches

- Confusion

- Gastrointestinal issues like diarrhea

- Kidney dysfunction

Hyponatremia, or low sodium levels in the blood, a critical and unique marker of this infection

Hyponatremia: A Clue to Legionella

Hyponatremia, one of the hallmark signs of Legionnaires’ disease, is often absent in other pneumonias. This is one of the unique symptoms of Legionnaires' that distinguishes from pneumonia. It results in dangerously low sodium levels, which can trigger symptoms ranging from mild fatigue and nausea to severe complications like confusion, seizures, or coma.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), hyponatremia often appears early in the course of a Legionella infection and should alert clinicians to consider Legionella pneumonia in patients with respiratory symptoms and abnormal lab findings. Its presence can help guide early diagnosis and prompt treatment, which is critical given the disease’s potential severity.

Long-Term Effects: Is There a “Long Legionnaires’”?

Much like long COVID, survivors of Legionnaires’ disease are now reporting symptoms that persist long after the acute infection has cleared.

These post-acute effects, also seen in other forms of pneumonia, include:

- Chronic fatigue

- Brain fog or cognitive dysfunction

- Decreased quality of life

- Ongoing respiratory issues

- Muscle weakness and joint pain

But what if Legionnaires’ disease leaves a unique post-infection footprint?

That’s the central question behind a new prospective cohort study conducted by researchers in Switzerland. Published in Swiss Medical Weekly, the LongLEGIO study is the first of its kind to compare the long-term effects of Legionnaires’ disease to other forms of bacterial community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

Inside the LongLEGIO Swiss Study

From June 2023 to June 2024, researchers recruited 59 patients with confirmed Legionnaires’ disease and 60 matched patients with Legionella test-negative CAP. Participants were closely matched by age, sex, hospital type, and timing of diagnosis.

Patients were assessed at four key time points:

- During the acute phase (baseline)

- 2 months after treatment

- 6 months after treatment

- 12 months after treatment

The study used patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), structured questionnaires to capture symptoms often missed in traditional hospital data. These included:

- Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

- Persistent fatigue

- Need for continued healthcare

- New or lingering symptoms

What the Baseline Data Reveals

Initial findings already highlight striking differences between the two groups. While the median age for both was 69, patients with Legionnaires’ disease were more likely to experience extrapulmonary symptoms. Notably:

- Muscle aches were reported by 51.8% of Legionnaires’ patients, compared to 25.9% of CAP patients.

- Fever was reported in 89.3% of Legionnaires’ cases vs. 76.3% in CAP.

- ICU admissions were higher among Legionnaires’ cases (13.6% vs. 8.3%).

Additionally, Legionnaires’ patients had a higher prevalence of chronic kidney failure (15.3% vs. 10%) and better pre-illness quality of life than their CAP counterparts, who tended to have more comorbidities such as COPD, cancer, and immunosuppression.

These early differences are critical because they suggest that Legionella may cause a distinct form of post-acute infection syndrome, akin to long COVID but possibly rooted in a different biological mechanism.

When Do Symptoms Begin, And How Long Do They Last?

Legionnaires’ disease symptoms typically begin 2 to 10 days after exposure, but the timeline varies based on individual health and level of exposure. Initially, it may mimic the flu:

- Headache

- Chills

- Muscle pain

- High fever (often >104°F)

- Fatigue

As the disease progresses, more severe or unique symptoms may surface, such as:

- Cough (often dry at first)

- Gastrointestinal issues like diarrhea or nausea

- Confusion or disorientation

- Signs of hyponatremia like fatigue, poor concentration, or seizures

For most patients, acute symptoms resolve within 2 to 4 weeks, but that’s not the end of the story.

Based on evidence from pneumonia survivors and early data from the LongLEGIO cohort, recovery can take several months, especially for those who had severe illness requiring ICU care. Lingering fatigue, shortness of breath, cognitive issues, and poor stamina can persist for 6 to 12 months or more.

Some patients, even after a year, may still experience reduced quality of life and ongoing healthcare needs, a pattern increasingly recognized across other infectious diseases but still under-researched in Legionnaires’.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited