- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Not Cleaning Your Face Before Sleeping? These Tiny Bugs Might Be Feasting On Your Skin

Credits: Health and me

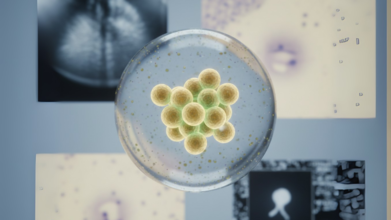

Demodex Mites

You may assume falling asleep without washing your face is just a lazy-night ritual but what if skipping that speedy cleanse invited an invisible microscopic to call your skin home? Say hello to Demodex folliculorum, the teeny microscopic mites that live, feed, and even reproduce on your face — most especially at night. While they're a natural part of the skin ecosystem, abandoning skincare can cause these little critters to thrive in some uncomfortable manners.Demodex mites are tiny, eight-legged invertebrates that live on the human face, specifically in and around hair follicles. They are just 0.15 to 0.4 millimeters in size, invisible to the naked eye but numbering dozens or even hundreds at times — as many as five per square centimeter of skin. That may sound creepy, but almost every adult human carries these mites. They exist mainly on sebum (your natural skin oil) and dead skin cells, performing a pretty harmless, even cleaning function in normal circumstances.

Consider them micro custodians: they suck up the skin flakes and extra oils that collect during the day. But when their numbers get out of hand, which typically happens due to poor hygiene or compromised immunity, their presence becomes a problem.

What Happens While You Sleep 'Mite-fully'?

Demodex mites are active at night. They come out of your pores when the sun sets, excelling in the lack of UV light — which is toxic to their DNA. As you sleep, they dine, crawl, and mate on your skin's surface. What's even more interesting (and somewhat alarming) is that they're fueled by melatonin, a hormone your body makes to assist in sleeping.

For their services to clean our pores, we unwittingly provide them with melatonin as fuel — a strange, symbiotic relationship that only shows up if something goes amiss.

When They 'Mite' Cause Trouble?

While harmless in small quantities, Demodex mites can lead to skin problems if they overpopulate — a condition known as demodicosis. In the opinion of Dr. Richard Locksley, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, such overpopulation can lead to a variety of skin and eye conditions, including:

- Rosacea

- Blepharitis (eyelid inflammation)

- Acne-like breakouts

- Itchy, inflamed skin

Immunocompromised people are especially vulnerable. When your immune system can't keep mite numbers in check, allergy and infection can follow. Ironically, your own sleeping habits — or lack thereof — can determine their level of activity. Lack of sleep boosts oil secretion, which provides mites with even more to munch on.

How Skipping Face Washing Adds To the Mite Population?

Letting makeup, grime, sunscreen, and impurities sit on your skin overnight can provide an all-you-can-eat buffet for Demodex mites. Left behind, these layers seal excess oil and dead skin cells — prime breeding ground for mites.

Also Read: Pop Star Jessie J Diagnosed With Early-Stage Breast Cancer; What Are The Signs Women Often Ignore?

This is particularly troublesome in the area around the eyes. Eyelash follicles tend to be a breeding ground for mite overgrowth, particularly when mascara, eyeliner, or false lashes are not removed effectively. This results in irritation, plugged glands, and increased susceptibility to such conditions as blepharitis.

One of the most fascinating findings appears in a 2022 paper in Molecular Biology and Evolution, which indicates Demodex mites are becoming permanent residents of the human body — literally. Scientists discovered that the mites are losing unnecessary genes as a result of their snug, predator-free existence on human faces.

Actually, their body structures are so sparse that single-cell muscles control each of their legs. They also have a reverse process of maturation — losing cells as they mature rather than adding them. Since such close biological incorporation, scientists believe that one day they will be able to integrate genetically with human hosts. It may sound like science fiction, but it's a possibility biologically.

Should You Be Worried?

For healthy individuals, there's no reason to panic. Demodex mites are not dangerous per se. In fact, they're so widespread they're actually thought of as part of the skin microbiome. But they can become an issue when individual hygiene is lax — especially before bedtime. Here's what you can do:

- Always wash your face at night. Use a light, non-comedogenic cleanser that strips away oil and debris.

- Remove eye makeup and false lashes. These are usual sites mites over-colonize.

- Don't neglect your sleep. Lack of sleep heightens sebum production, inviting mites to flourish.

- Consult a dermatologist if you have persistent redness, itchiness, and inflammation in the skin.

Your evening skincare routine isn't vanity, it's a defense system against an unseen, millennia-old species that lives on your face. Though Demodex mites are generally harmless housemates, bad hygiene and broken sleep habits can cause them to become freeloaders with no plans to leave.

Dermatologist Reveals Why Using The Same Skincare Day And Night Could Be Ruining Your Skin

Credits: Health and me

Your skincare shelf might be quietly sabotaging your glow—and you don’t even know it. Think about it: the same cream you swipe on at 7 a.m. is also applied at 11 p.m. But your skin isn’t static; it’s a living, breathing organ with different priorities depending on the time of day. Morning skin is on defense, battling sunlight, pollution, and blue light, while nighttime skin is in repair mode, regenerating and replenishing. Using the same products both times may be convenient, but convenience could come at the cost of healthier, radiant skin.

Skincare seems simple on the surface—wash, moisturize, repeat. Many of us follow the same routine morning and night, believing that if a product works once, it works all day. But according to dermatologist Dr. Vikram Lahoria, this approach may be doing more harm than good. Your skin operates on a circadian rhythm, and the way it behaves during the day differs significantly from its nighttime activities. Understanding these differences—and adjusting your routine accordingly can be the difference between healthy, glowing skin and clogged pores, premature aging, or irritation.

How Your Morning Skincare Is A Shield?

Dr. Lahoria explains, “During the day, your skin is exposed to sunlight, pollution, dust, and even the blue light from screens. Its main role is protection. That’s why your morning routine should focus on creating a barrier against these environmental stressors.”

A typical morning routine starts with a gentle cleanser to remove oils and sweat accumulated overnight. This is followed by a light, hydrating moisturizer that won’t feel greasy or clog pores. The most crucial step in your AM routine is sunscreen. No matter the weather, SPF shields your skin from UV rays, reducing the risk of premature aging, pigmentation, and even skin cancer.

Adding an antioxidant serum, particularly one with vitamin C, can further protect against free radicals generated by pollution and UV exposure. “Think of it as giving your skin armor before stepping into the world,” says Dr. Lahoria.

How Your Night Skincare Is To Heal and Recharge?

Once the sun sets and the day winds down, your skin switches gears. “Nighttime is when your skin works hardest to repair itself,” Dr. Lahoria notes. Without sunlight and environmental stressors, skin cells can focus on regeneration and replenishment.

Night creams and serums are designed to support this process. Ingredients like retinol, peptides, hyaluronic acid, and glycolic acid target fine lines, improve texture, and lock in moisture. A thorough cleanse is essential before applying these products to remove makeup, sweat, and dirt that could block pores overnight.

“Nighttime is when your skin absorbs products most efficiently. The lack of UV exposure means potent actives like retinol can work without the risk of sun-induced irritation,” explains Dr. Lahoria.

Why Using the Same Products All Day Can Backfire?

Using identical products morning and night ignores the skin’s shifting priorities. “It’s like feeding your body the same meal for breakfast and dinner,” says Dr. Lahoria. “In the morning, your skin needs protection. At night, it needs repair. One product cannot optimally serve both functions.”

Daytime exposure to retinoids or AHAs, for instance, can increase sensitivity to sunlight, potentially causing irritation, pigmentation, or damage. Conversely, using sunscreen at night is unnecessary, and while it won’t harm your skin, it doesn’t contribute to repair either. Tailoring your routine ensures that ingredients work when they are most effective, rather than canceling each other out or creating unintended side effects.

Why The Order of Products Is Important?

Timing is not the only consideration—the order in which you apply your skincare products matters too. Dr. Lahoria advises layering from thinnest to thickest. This ensures lightweight serums penetrate deeply before being sealed in by heavier creams or oils. Incorrect layering can hinder absorption or even reduce the efficacy of active ingredients.

For example, a vitamin C serum should be applied before moisturizer, while a heavier night cream should go last. By following this approach, each product can work as intended, maximizing benefits without waste or interference.

Personalising Your Routine to Your Skin’s Clock

Your skin, like your body, has a circadian rhythm. During the day, its priority is defense; at night, it focuses on repair. “Ever wonder why your skin behaves differently in the morning than it does at night? That’s your internal clock at work,” Dr. Lahoria points out.

Adjusting your routine according to this natural rhythm ensures your skin gets the right nutrients at the right time. In the morning, protect; at night, repair. Over time, this approach improves skin health, prevents premature aging, and enhances the results from the products you invest in.

Morning and Night Routine Tips

Dr. Lahoria summarizes an effective framework:

Morning:

- Gentle cleanser to remove overnight oils

- Light moisturizer for hydration

- SPF to protect against UV damage

- Optional antioxidant serum for pollution defense

Night:

- Thorough cleanse to remove dirt, makeup, and pollutants

- Serums or creams containing retinol, peptides, hyaluronic acid, or glycolic acid

- Night cream to lock in moisture and support cell repair

Following these guidelines ensures that your skin is supported according to its natural needs, rather than treated with a one-size-fits-all approach.

Skincare is not just about selecting the “right” products—it’s also about using them at the right time. Dr. Lahoria concludes, “Your morning and evening routines should act like a tag team. Each plays its role in protecting, repairing, and energizing your skin. Your clock isn’t just ticking, it’s guiding your glow.”

By understanding your skin’s natural cycles, choosing the right ingredients for day and night, and applying them in the correct order, you ensure your skin remains healthy, radiant, and resilient—without unnecessary irritation or damage.

Half of People With Diabetes Go Undiagnosed, Lancet Study Warns

(Credit- Canva)

A disease that globally affects people, numbers ranging in the millions, Diabetes is a silent killer that many people suffer with. 2022 stats showed that the number of people who were living with diabetes was 830 million, which steadily rose from the 200 million in 1990. According to the World Health Organization, more than half of the people who had diabetes live or are living without getting medication for it. A lot of them didn’t even know they had diabetes, and a recent study revealed how many exactly.

Before you know the number ask yourself a question: Do you know your blood sugar level?

This is a question that either people who have gotten their sugar levels tested would know, or cautious people who get regular check ups would know. A new study suggests that many people with diabetes don't, which could lead to serious health issues down the line. According to a study published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, a staggering 44% of people aged 15 and older who have diabetes are undiagnosed.

The study, which looked at data from 204 countries, found that about one in nine adults worldwide has diabetes. In the U.S. alone, 11.6% of Americans have the condition. While higher-income countries are generally better at diagnosing people, the problem is widespread. Globally, only 56% of people with diabetes are aware of their condition.

Why Are So Many Diabetic People Undiagnosed?

A surprising finding is that younger people are much less likely to be diagnosed. Only 20% of young adults with diabetes know they have it. This is partly because routine screenings are more often recommended for people over 35. Many people with diabetes don't experience clear symptoms until complications—like heart, kidney, or nerve damage—start to appear, which is more common in older adults.

Early diagnosis is crucial. Experts say that knowing you have diabetes early allows for timely management that can prevent or delay these severe, long-term complications.

Many people with diabetes have no symptoms in the early stages, which is why regular screenings are so important. However, be on the lookout for these common signs:

- Increased thirst or hunger

- Frequent urination

- Blurry vision

- Unexpected weight loss

- Fatigue

Even after diagnosis, there's another challenge: proper management. The study found that only about 40% of people with treated diabetes were able to get their blood sugar under control. This highlights the need for better support and treatment plans to help people manage their condition effectively.

Can You Prevent Diabetes?

While you can't prevent Type 1 diabetes, you can significantly lower your risk of developing the more common Type 2 diabetes. Here are some simple steps you can take:

Improve your diet. Eat fewer red and processed meats, and incorporate more plant-based foods, like a Mediterranean diet.

Limit ultra-processed foods. Choose whole foods like fruits and nuts over highly processed snacks.

Stay active. Regular physical activity, such as a 15-minute walk each day, can lower your risk of developing diabetes and other chronic diseases.

What A Stage 0 Cancer Diagnosis Really Means? Oncologist Explains

Credits: Health and me

When you hear the word cancer, your first instinct may be fear but not all diagnoses carry the same weight. One of the most misunderstood terms in oncology is Stage 0 cancer, also called carcinoma in situ. It is, in fact, the earliest stage possible, where abnormal cells are detected but have not yet spread.

Cancer is rarely a one-size-fits-all diagnosis. Among its many stages, Stage 0 stands out as a unique opportunity, an early alert rather than a full-blown disease. Also known as carcinoma in situ, it signals the presence of abnormal cells confined to their original location, offering patients the best chance for effective intervention and cure.

To demystify what this really means for patients and families, we spoke with Dr. Nikhil Suresh Ghadyalpatil, Director of Medical Oncology at Apollo Cancer Centre, Hyderabad, who has treated countless patients diagnosed at this critical stage.

What Is Stage 0 Cancer Diagnosis?

Stage 0 cancer, or carcinoma in situ, represents the earliest form of cancer. Abnormal cells exist but remain localized, without invading surrounding tissues or spreading to other organs. Though non-invasive, these cells have the potential to progress, making timely detection and treatment essential to prevent future complications.

Dr. Ghadyalpatil explains it with a simple analogy, “Think of Stage 0 cancer like finding a weed seed in your garden before it sprouts. You’ve caught it at the very beginning, before it has grown roots or spread.”

At this stage, the cells are considered cancerous but remain “in situ,” meaning “in their original place.” They haven’t invaded surrounding healthy tissue or metastasized to other parts of the body.

That’s important because once abnormal cells begin spreading, treatment becomes more complex. At Stage 0, the odds are overwhelmingly in favor of successful treatment, often with less invasive procedures.

Myths Around Stage 0 Cancer Diagnosis

The diagnosis often sparks confusion. Patients wonder if it’s “real cancer” or just a warning sign.

Myth 1: Stage 0 isn’t true cancer.

“The cells are cancerous, just non-invasive,” says Dr. Ghadyalpatil. “If untreated, many can progress to invasive cancer. That’s why we treat it seriously at this stage.”

Myth 2: I should have noticed symptoms.

In reality, Stage 0 rarely causes pain, lumps, or any visible changes. It’s typically picked up during routine screenings—a mammogram, Pap smear, colonoscopy, or skin check. “Patients often blame themselves for missing signs, but the truth is, the screening test did exactly what it was supposed to do: catch cancer early,” Dr. Ghadyalpatil emphasizes.

Myth 3: It will definitely become invasive.

Not all Stage 0 cancers turn dangerous. But since doctors cannot predict which cases will progress, the safer medical approach is to treat or closely monitor.

How Is Stage 0 Cancer Detected?

Stage 0 cancers are often silent, causing no symptoms, and are usually discovered through routine screenings. Mammograms, Pap smears, colonoscopies, and skin checks are the most common methods, often followed by a biopsy to confirm abnormal cells. Early detection is key to achieving high treatment success and long-term survival. Because the disease is silent, screenings are the unsung heroes.

- Mammograms detect Ductal Carcinoma in Situ (DCIS) in breast tissue.

- Pap smears reveal precancerous or cancerous changes in cervical cells.

- Colonoscopies identify and remove polyps with abnormal cells before they evolve.

- Skin checks help dermatologists catch non-invasive skin cancers early.

Diagnosis is usually confirmed with a biopsy, where a small tissue sample is examined under a microscope.

What Are The Treatment Options for Stage 0 Cancer Diagnosis?

A Stage 0 diagnosis doesn’t automatically mean aggressive therapy. Treatment is personalized based on the cancer type and location. Surgery is the most common route. Doctors remove the abnormal cells and sometimes a margin of healthy tissue for safety.

Radiation therapy may follow surgery to eliminate residual cells and reduce recurrence risk. Hormone therapy can be recommended for hormone-sensitive cancers, lowering the chance of future disease.

Active surveillance is an option in some cases, especially when the risk of progression is low. Doctors may suggest close monitoring with regular checkups instead of immediate treatment.

“The ultimate goal is to ensure those abnormal cells don’t get a chance to cause harm,” says Dr. Ghadyalpatil. “But it doesn’t always mean drastic treatment. In many cases, simple procedures and follow-up are enough.”

Why Early Cancer Detection Changes Prognosis?

The greatest message a Stage 0 cancer diagnosis carries is hope. It underscores the effectiveness of preventive healthcare.

“This is proof that routine screenings save lives,” stresses Dr. Ghadyalpatil. “When we catch cancer at Stage 0, the prognosis is excellent. Patients have the best possible chance of a cure.”

Unlike later stages where cancer spreads and treatments become more complex, a Stage 0 diagnosis often means:

- Less invasive treatment

- Shorter recovery periods

- Significantly higher survival rates

For patients, hearing the word “cancer” can trigger anxiety, even when it’s Stage 0. That’s why oncologists emphasize context. “I always tell my patients, you caught it at the right time. This is not a death sentence, it’s a wake-up call that your screening worked,” says Dr. Ghadyalpatil.

This reassurance helps patients focus on proactive steps instead of panic.

Stage 0 diagnoses also highlight broader questions about preventive healthcare. Many people delay or avoid screenings due to fear, stigma, or cost. Yet, as Dr. Ghadyalpatil points out, “Screenings are our frontline defense. Without them, Stage 0 cancers would silently progress, robbing us of the window for simple, effective treatment.”

Investing in regular checkups isn’t optional, it’s essential. A Stage 0 cancer diagnosis is not the end of the road; it’s the beginning of timely action. With proper treatment and monitoring, most people go on to live full, healthy lives.

“The most important thing,” Dr. Ghadyalpatil concludes, “is to understand that Stage 0 cancer is an opportunity. You’ve caught it early. Now, with the right medical plan, you can move forward with confidence.”

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited