- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

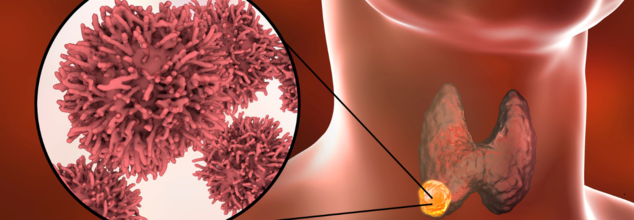

Oral Sex Is The Leading Risk For Throat Cancer

Oral sex is the number one leading risk factor for causing throat cancer. Throat cancer is caused by a virus called HPV or the Human Papillomavirus. This virus is also known to cause anal and cervical cancers. Despite many girls being vaccinated against the leading cancer-causing strain of HPV, throat cancer cases are rising. The reason is that the vaccines do not necessarily protect against the wart-causing strains, also a type of HPV.

The incidents of throat cancer have also been slowly rising since mid-90s, and one explanation for this is through oral sex.

It is not about the number of times one has performed oral sex, but the number of different partners that one person has done it with. While the baseline risk of throat cancer is actually pretty low at .2% in women and .7% in men, performing oral sex on just 5 different partners can increase the risk of throat cancer by 2.5 times.

While one can think of limiting their sexual partner, if that is not the possibility, using a dental dam can promote a healthier and safer oral sex experience.

What Is Oral Sex?

It involves using the mouth to stimulate the genitals or genital area of a partner and can also lead to sexually transmitted infections (STI) such as:

- Gonorrhea

- Genital herpes

- Syphilis

- Chlamydia

- HPV

HPV And Cancer

While oral sex does not directly cause cancer, HPV can trigger changes in the infected cells. Its genetic material becomes part of cancer cells and causes them to grow. In the US, 70% of throat cancers are caused by HPV.

A person's body clears HPV in 2 years, however, those who smoke are less likely to be able to clear an HPV infection because smoking damages immune cells in the skin.

Who Are At More Risk?

Other than oral sex, people who smoke regularly can be at risk of throat cancer. Smoking tobacco is the most important factor for all cancers of the head and neck, including throat cancer. If you are exposed to dangerous substances like paint fumes, wood dust and shavings, or chemicals used in plastic, metal, and textile industries or are alcoholic, you may be at an increased risk of developing a throat cancer.

Signs And Symptoms

- A mouth sore or ulcer that does not heal within 3 weeks

- Soft tissues of mouth becoming discoloured

- Pain while swallowing and a feeling as if food sticks in the throat

- Swelling with no pain in the tonsils

- Pain while chewing

- Ongoing sore throat or croaky voice with persistent cough

- Numbness in mouth or lips

- Swelling or lump in mouth

- Painless lump outside of the neck

- One-sided earache

COVID-19 Masks Pose A Greater Threat To Our Health Now, Years After The End Of The Global Pandemic: Study

During the COVID pandemic, masks were mandatory equipment that everyone needed to wear. Although it may have seemed like a big deal back then, it later on became a much more accepted part of healthy living. As the pandemic came to an end, many people discarded their used masks, and we all went on with our lives. However, in the matter of few years of global mask usage, we may have created a bigger problem than we may have realized.

A new study has found that the popular N95 masks and similar respiratory masks are more damaging to the environment than surgical masks. Billions of these masks were thrown away improperly during the COVID-19 pandemic, and all of them are causing major environmental problems.

According to a report published in the journal Environment Pollution, the use of disposable masks went up by almost 9,000% in just a few months in 2020. At the peak of the pandemic, people were using about 129 billion disposable masks every month around the world. These masks are not designed to be recycled through normal methods, and many have ended up on our streets, in our parks, and in our oceans.

What Health Problems Have COVID Masks Created?

The biggest issue with these masks is that they shed tiny plastic pieces called microplastics. A separate study discovered that N95 masks release 3 to 4 times more microplastics into water than regular surgical masks. These tiny plastic particles are mostly made of polypropylene.

When they get into our environment, they can be harmful to both humans and animals. They can potentially cause serious health problems like birth defects and cancer. The study also found that N95 masks released a wider variety of other chemicals and plastic pieces, making them a bigger environmental concern than other types of masks.

What Health Threats Do Microplastics Pose?

We are exposed to microplastics constantly. They come from sources like clothing, cosmetics, cleaning products, and even the food we eat, including seafood and produce. It's no surprise, then, that microplastics have been found throughout the human body, in our blood, liver, kidneys, and even in a baby's first stool and a mother's breast milk.

According to Harvard Health, early studies on human cells and animals suggest that microplastics can cause a range of health problems. They may lead to inflammation and damage to organs like the lungs and liver. Researchers have also found that microplastics can harm DNA and change how genes work, which are factors linked to cancer.

Chemicals from these particles, such as BPA, can disrupt our hormones and affect our nervous and reproductive systems. In fact, some animal studies show that microplastics might even cause reproductive issues. Additionally, there's a concern that these tiny plastics can carry germs and make other toxic substances even more dangerous to our bodies.

How Can We Improve This Mask Health Hazard?

The researchers who conducted this study are calling for new rules to deal with the environmental and health risks from disposable masks. They point out that we have a big gap in how we handle plastic waste and how we regulate these products. To solve this problem, they say we need everyone to work together: scientists, the companies that make the masks, waste managers, governments, and everyday people. The goal is to create new policies based on scientific evidence to make sure we can protect our health without causing more harm to our planet.

Obesity In Children Is Now More Common Than Underweight Children: UNICEF Reveals

(Credit- Canva)

For the very first time, there are now more kids around the world who are overweight or obese than there are who are underweight. A new report from UNICEF, an organization that works for children, shared this news. It says that 1 in 10 children aged 5 to 19—that's 188 million kids—are now living with obesity. This puts them at a higher risk of getting serious health problems later in life.

The report looked at information from over 190 countries and found that since the year 2000, the number of underweight children has gone down, but the number of kids with obesity has gone up by a lot. This is happening in almost every part of the world, except for a couple of regions in Africa and Asia.

What Is Causing The Rise In Obesity?

UNICEF's report highlights that this rise in obesity is not a matter of personal choice but is driven by unhealthy food environments. Ultra-processed and fast foods are now everywhere—in stores, schools, and online, thanks to powerful digital advertising that targets young people.

For example, a global poll found that 75% of young people recalled seeing ads for sugary drinks and fast food in just one week. This kind of marketing makes them want to eat these unhealthy foods more. These foods are high in sugar, unhealthy fats, and salt, and are replacing the nutritious foods children need to grow and develop.

Some countries are taking action. In Mexico, where processed foods make up 40% of children's daily calories, the government has banned the sale of these items in public schools, which will benefit over 34 million children.

How Can We Lower The Risk Of Global Obesity?

The economic and health costs of this trend are staggering. If we don't act, the global cost of being overweight and obese is expected to exceed $4 trillion annually by 2035. To fight this growing problem, UNICEF is urging governments and other organizations to take immediate action:

Better Food Policies

Governments should create mandatory policies to improve children's diets. This includes clear food labels so families know what's in their food, restricting how junk food is advertised to kids, and using taxes or financial support to make healthy food more affordable.

Encourage Healthier Choices

We need to launch initiatives that teach families and communities to demand and support healthier food options. By empowering people to make better choices, we can build a culture where nutritious eating is the standard, not the exception, in every neighborhood.

Ban Junk Food in Schools

Schools must become safe havens for healthy eating. This means completely stopping the sale of ultra-processed foods and junk food on school grounds. We also need to ban food companies from marketing their products or sponsoring any school events.

Protect Public Health

It's crucial to set up strong rules to protect public health policies from being influenced by big food companies. These safeguards will ensure that government decisions about what kids eat are based on science and public well-being, not corporate profit.

Help Vulnerable Families

We must expand financial aid programs to help families with low incomes afford healthy and nutritious food. By addressing poverty and increasing access to good food, we can ensure every child has the foundation they need for a healthy life.

Why Your Dirty Pillowcase Could Be Damaging Your Skin And Hair More Than Pollution

Credits: iStock

Why Your Dirty Pillowcase Could Be Damaging Your Skin And Hair More Than Pollution

Bacteria, fungi, and trapped oils transfer to your scalp and skin, causing acne, dandruff, hair breakage, and irritation. Regular washing and choosing the right fabrics can prevent these hidden beauty hazards.

You slip into bed, exhausted, and rest your head on a pillowcase that hasn’t seen a wash in a week. Or perhaps you grab a towel from the rack after a shower, unaware that it’s been sitting damp for days. It seems harmless, even routine—but what if these everyday fabrics were quietly sabotaging your skin and hair? While we obsess over serums, masks, and hair oils, the fabrics we touch daily may be undermining all our efforts.

The issue is subtle but significant. Fabrics like pillowcases and towels can become incubators for bacteria, fungi, dust mites, and trapped oils, sweat, and dead skin cells. Over time, this microbial buildup doesn’t just sit there—it actively transfers to your skin and scalp, setting the stage for a range of problems from breakouts to hair fall.

Dermatologist Dr. Gajanan Jadhao, a Hair Transplant Surgeon and Anesthesiologist, explains, “Dirty pillowcases and towels may seem harmless, but they can silently wreak havoc on your skin and hair health. When not washed regularly, they become breeding grounds for bacteria, fungi, and dust mites, which easily transfer onto your scalp and skin. This can lead to clogged pores, acne breakouts, fungal infections, dandruff, itchy scalp, and even increased hair fall. The natural oils, sweat, and dead skin cells trapped in these fabrics further worsen the problem, weakening hair follicles and irritating the skin.”

He emphasizes that this is not a minor concern. “Since we spend hours sleeping on pillows and use towels daily, poor hygiene can continuously expose us to these harmful microorganisms. Maintaining clean pillowcases and towels by washing them regularly with hot water and drying them properly is a simple yet powerful habit to protect your scalp, hair, and skin health—keeping them fresh, infection-free, and glowing.”

How Often Should Pillowcases and Towels Should Be Cleaned?

“Pillowcases and towels should be washed at least twice a week to prevent hidden skin and scalp problems. Always wash them with a mild detergent and ensure they are completely dried in sunlight or a hot dryer, as damp fabrics encourage microbial growth. Regular cleaning not only maintains hygiene but also helps protect your skin’s glow and scalp health, keeping infections at bay,” according to Dr. Jadhao.

What Is The Link Between Dirty Fabrics, Acne And Hair Damage?

Many people underestimate how directly unwashed fabrics can affect skin and hair. Dr. Jadhao says, “Dirty fabrics like unwashed pillowcases, towels, or bedsheets can directly contribute to acne, dandruff, and even hair breakage. When you come in contact with dirty fabrics, the trapped dirt and microbes transfer to your skin and scalp, clogging the sebaceous glands and leading to pimples, acne flare-ups, and scalp irritation. On the scalp, this buildup can weaken hair follicles, causing dandruff, itching, and hair breakage. Maintaining clean fabrics is essential to keep your skin clear and hair healthy.”

Choosing the Right Pillowcase Fabric

Not all fabrics affect skin and hair equally. “Cotton pillowcases are breathable but tend to absorb too much moisture, stripping natural oils from the skin and hair, which can lead to dryness and frizz. Silk pillowcases, on the other hand, are smooth and reduce friction, helping to prevent wrinkles, tangles, and hair breakage, though they don’t absorb much sweat or oil. Microfiber pillowcases offer superior absorption, making them effective at wicking away moisture, but frequent use may over-dry the skin and scalp if not balanced with proper care. Choosing the right fabric depends on individual skin and hair needs,” Dr. Jadhao explains.

Early Warning Signs

You don’t have to wait for full-blown breakouts or dandruff to realize your fabrics are a problem. Dr. Jadhao notes, “Dirty or poorly maintained fabrics can cause dryness, frizziness, and increased hair tangling due to constant friction and moisture absorption. On the skin, you may notice itchiness, mild redness, or small bumps that later develop into boils or acne. A persistently oily or greasy feeling on the face and scalp after rest or drying with a towel is another clue. Recognizing these early symptoms allows you to take corrective action—like washing fabrics more often—before serious problems develop.”

Ultimately, while elaborate beauty routines have their place, Dr. Jadhao shares that some of the most effective measures for skin and hair health start in the laundry room. With consistent care, the fabrics we touch daily can support, rather than sabotage, our efforts to stay healthy, glowing, and confident.

Dr. Gajanan Jadhao, is a Hair Transplant Surgeon, Dermatologist, and Anesthesiologist- Founder and Director of La Densitae Hair Transplant Clinic in India

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited