- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

UAE Mandates Premarital Genetic Testing: Why Is It Important?

Genetic Testing (Credit: Canva)

Premarital genetic testing will soon be mandatory for Emirati couples in Abu Dhabi, marking a significant step in public health policy to reduce the risk of hereditary diseases. The initiative, which comes into effect on October 1, requires couples to undergo screening to assess the likelihood of passing genetic disorders to their future children, fostering informed family planning decisions.

The screening process will identify if either partner carries genes linked to hereditary conditions such as sickle cell anemia and thalassemia. These conditions can lead to serious health complications for offspring, including loss of vision and hearing, blood clotting disorders, developmental delays, hormonal imbalances, and organ function failures. By detecting these genetic risks early, couples can make more informed choices about their family’s health.

This comprehensive genetic screening will be available at 22 primary care centers throughout Abu Dhabi, including locations in Al Dhafra and Al Ain. The tests will cover 570 genes associated with over 840 inherited defects, providing a thorough assessment of potential health risks.

While India does not have mandatory premarital genetic testing, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) has issued guidelines for genetic counseling and testing. The UAE’s initiative reflects a growing recognition of the importance of genetic health in family planning, aiming to mitigate the transmission of hereditary diseases in a region where genetic disorders have been a concern.

The move has been welcomed by health experts, who emphasize that such proactive measures can lead to healthier future generations. By encouraging couples to undergo genetic testing before marriage, the Abu Dhabi Health Authority hopes to decrease the prevalence of hereditary conditions and improve overall public health outcomes.

In addition to genetic testing, couples will receive counseling to help them understand the implications of their results and discuss options moving forward. This support system is designed to empower individuals and couples with the knowledge they need to make the best choices for their families.

Vaccines For Children Pose No Threat To Their Heart Health Or Other Health Issues: Study

(Credit-Canva)

Vaccines have been under public scrutiny for some times now. Many people have brought up their concerns regarding how vaccines can harm their health and how these focus on short-term health while ignoring the long-term well-being. Recently, the claims that vaccines can cause psychological issues like autism and ADHD have been brought up and aluminum in vaccines were questioned. Studies like a 2011 review published in the Current Medicinal Chemistry journal questioned the validity of these vaccines claiming that these can cause autoimmune diseases and the benefits of it are overstated.

However, a major study involving over 1.2 million people has found no connection between the small amount of aluminum in childhood vaccines and long-term health problems like autism, asthma, or diseases where the body attacks itself. The research, published on July 14 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, rigorously examined 50 chronic conditions, offering significant reassurance about vaccine safety.

What the Study Looked At

The study explored many health concerns, including:

- 36 types of autoimmune diseases (where the body's immune system mistakenly attacks its own healthy cells).

- Nine different types of allergies and asthma.

- Five brain development disorders, such as autism and ADHD.

Role of Aluminum in Vaccines

Aluminum is added to some vaccines to help the body build a stronger defense against diseases. It acts like a helper, making the vaccine more effective. However, this added aluminum has sometimes been a concern for people who doubt vaccine safety.The researchers behind this study say their work clearly shows that childhood vaccines are safe. This information should help parents feel confident when making choices about their children's health.

The study team looked at health records from Denmark. They followed people born between 1997 and 2018 until the end of 2020. This allowed them to compare children who received more aluminum in their vaccines before age two with those who received less. It's important to know that children who weren't vaccinated were not included in this particular study.

Clearing Up Past Misunderstandings

This new study also helped clear up confusion from an earlier study in 2022. That study had suggested that there is a link between aluminum in vaccines and asthma. However, many experts criticized that older study because it didn't properly separate the aluminum from vaccines from aluminum that comes from other common sources. For example, aluminum is naturally found in food, water, air, and even breast milk.

What Aluminum Does in Vaccines

In vaccines, aluminum is used as a "helper" called an adjuvant. This helper makes the body's immune system respond strongly to the vaccine. Without adjuvants, the vaccine might not work as well, or it could even do the opposite of what's intended, which is making the body less protected rather than more.

The aluminum in vaccines is present in very tiny amounts, and it's in the form of aluminum salts, which are very different from the actual metal aluminum. It's crucial for parents to understand that they are not injecting metal into children. Most of this aluminum leaves the body within about two weeks, though a very small amount can stay for years.

What This Means for Vaccine Safety

While no single study can prove something is completely safe, this new research adds to many years of studies that all show aluminum in vaccines is not harmful. It's the combined information from all these studies over time that truly shows how safe vaccines are.

Researchers stress that vaccines containing aluminum are a very important part of childhood immunization programs. They believe it's essential to keep politics out of discussions about this topic because children's health depends on these vaccines.

Pablo Escobar And Ecuador's Most Wanted Criminal, All Had This One Disease In Common - Gastritis

Credits: Canva, Wikimedia Commons, NBC

When you hear of the drug lord Pablo Escobar, you think of someone uncatchable, beyond the law. However, it is because of such a personality that we often forget that he too has everyday problems like us, including health issues, which may have cost their lives too.

"Gastritis won't leave me alone," was one of the phrases the drug lord mentioned during the calls he had with his son and wife. One day, these were the calls that made it possible to catch him. Not just him, but also Ecuador's wanted criminal 'Fito', José Adolfo Macias Vilamar, who is the leader of Los Choneros too suffered from the same. On June 25, he was finally captured.

Drug Lords And Heart Diseases

It is Fito's medicines that gave him away. It was in the bunker of his house, or the appropriate word for it would be a hole, out of which Fito appeared. But, how did the authority know he would be in that hole, in the property? The authorities found products for heartburn and gastritis, such as Diatrol, Dexopal, and Omeprazole. This is what made them certain that Fito in fact was there. They also found medicines for treating skin conditions, such as Platsul and Itrafung, an insulin used by him to treat his diabetes.

"Fito has a serious gastritis problem and is taking some medication," said Interior Minister John Reimberg. Gastritis and heartburn was also suffered by the founder of Medellín cartel, Escobar.

After escaping from La Catedral in 1992, Escobar began hiding from authorities without the power he had during much of his criminal heyday, which prevented him from accessing the drugs he used to treat his gastritis.

What Is Gastritis?

As per John Hopkins Medicine, it is inflammation of the stomach lining. Your stomach lining is strong. In most cases, acid does not hurt it. But it can get inflamed and irritated if you drink too much alcohol, have damage from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (called NSAIDs), or smoke.

What May Have Caused It?

For Drug lords, lavish parties, alcohol use, and extreme stress to find an escape is common. These are the exact causes of gastritis.

Lifestyle habits that can cause gastritis include:

- Drinking too much alcohol

- Smoking

- Extreme stress. This can be from serious or life-threatening health problems

- Long-term use of aspirin and NSAIDs

Health issues that too could lead to this:

- Infection caused by bacteria or viruses

- Major surgery

- Traumatic injury or burns

Diseases like autoimmune disorders, where you immune system attacks your body's healthy cells by mistake, or chronic bile reflux, where bile backs up into your stomach and food pipe (esophagus) could also cause gastritis.

Common Symptoms

- Stomach upset or pain

- Belching and hiccups

- Nausea and vomiting

- Feeling of fullness or burning in your stomach

- Loss of appetite

- Blood in your vomit or black stool. This is a sign that your stomach lining may be bleeding

Could It Lead To Complications?

Chronic gastritis hurts your stomach lining. It can raise your risk for other health problems. These include:

- Peptic ulcer disease. This causes painful sores in your upper digestive tract

- Gastric polyps. These are small masses of cells that form on the inside lining of your stomach

- Stomach tumors. These can be cancer or not cancer (benign)

- A hole (perforation) of the stomach

Medical Memoir: The History Of Period Care Through Years Of Menstrual Products' Evolution

Credits: Canva

'Medical Memoir' is a Health & Me series that delves into some of the most intriguing medical histories and unveils how medical innovations have evolved over time. Here, we trace the early stages of all things health, whether a vaccine, a treatment, a pill, or a cure.

Menstrual products have come a long way—from homemade cloth rags and belts to silicone menstrual cups and sleek, leak-proof underwear. The history of these products is as much about medical innovation as it is about cultural taboos, social shifts, and gendered marketing. While nearly half the world menstruates at some point, the journey toward safer, dignified, and sustainable period care has been anything but straightforward.

Ancient Origins: Creativity and Cultural Beliefs

Long before commercial products existed, women relied on locally available materials. In ancient Greece, tampon-like devices were reportedly made using lint wrapped around light wood. Egyptian women fashioned internal devices from softened papyrus, while Roman women used wool or cotton pads secured with belts. Meanwhile, Native American women used moss and buffalo skin, and in Equatorial Africa, grass rolls absorbed menstrual blood.

However, these were not necessarily used openly. Menstruation was frequently wrapped in superstition and shame. Ancient texts reveal contradictory beliefs: while Egyptian medical papyri regarded menstrual blood as medicinal, Roman and early Christian texts often considered it impure, even dangerous.

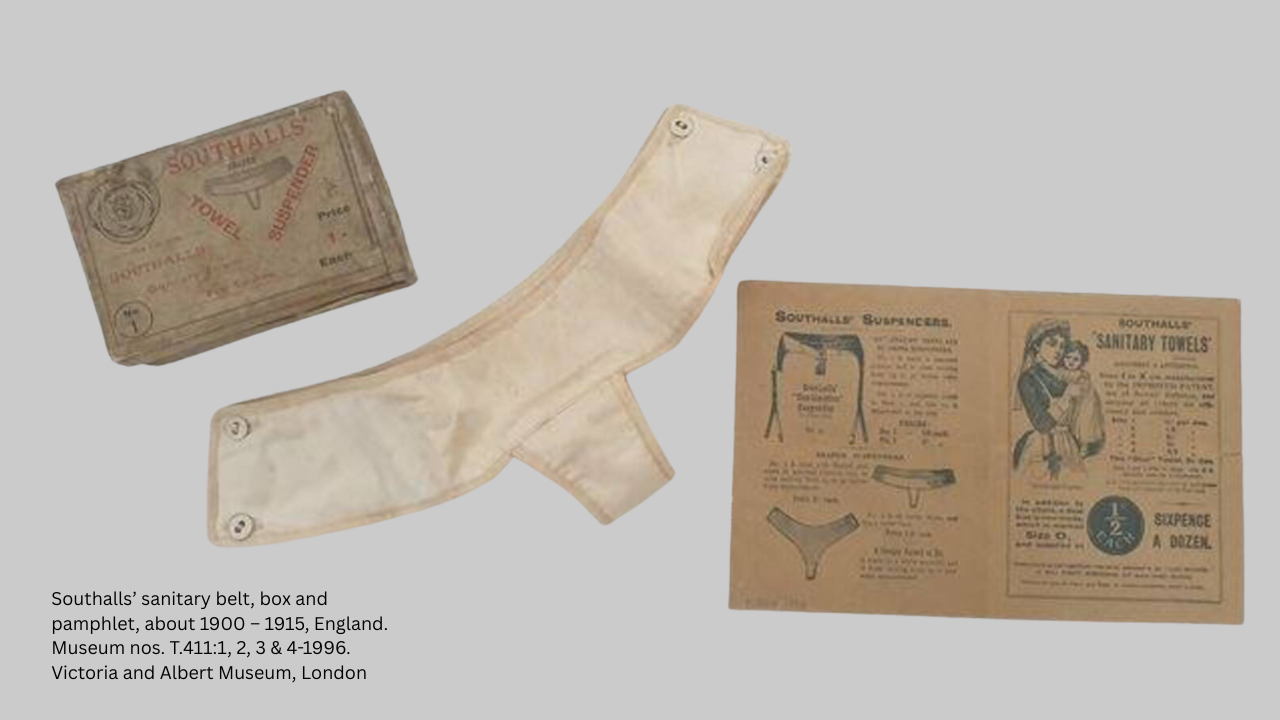

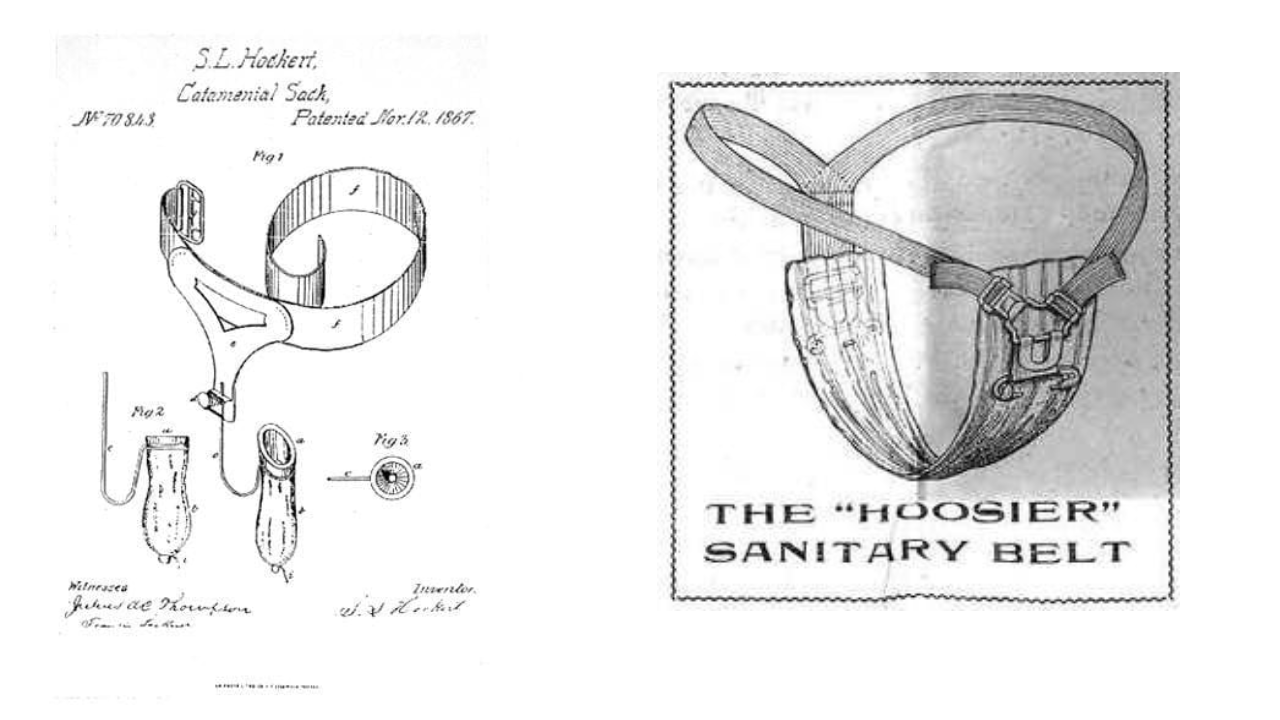

19th Century: Cloth Pads and the Birth of Sanitary Belts

By the 1800s, European and American women commonly used reusable cloth rags made from flannel or linen. These were washed and reused but posed hygiene concerns. The late 19th century saw the invention of the sanitary belt—a strap-on belt that held a pad in place. Brands like Southalls’ Shaped Towel Suspender marketed these belts for women “travelling by land or sea.”

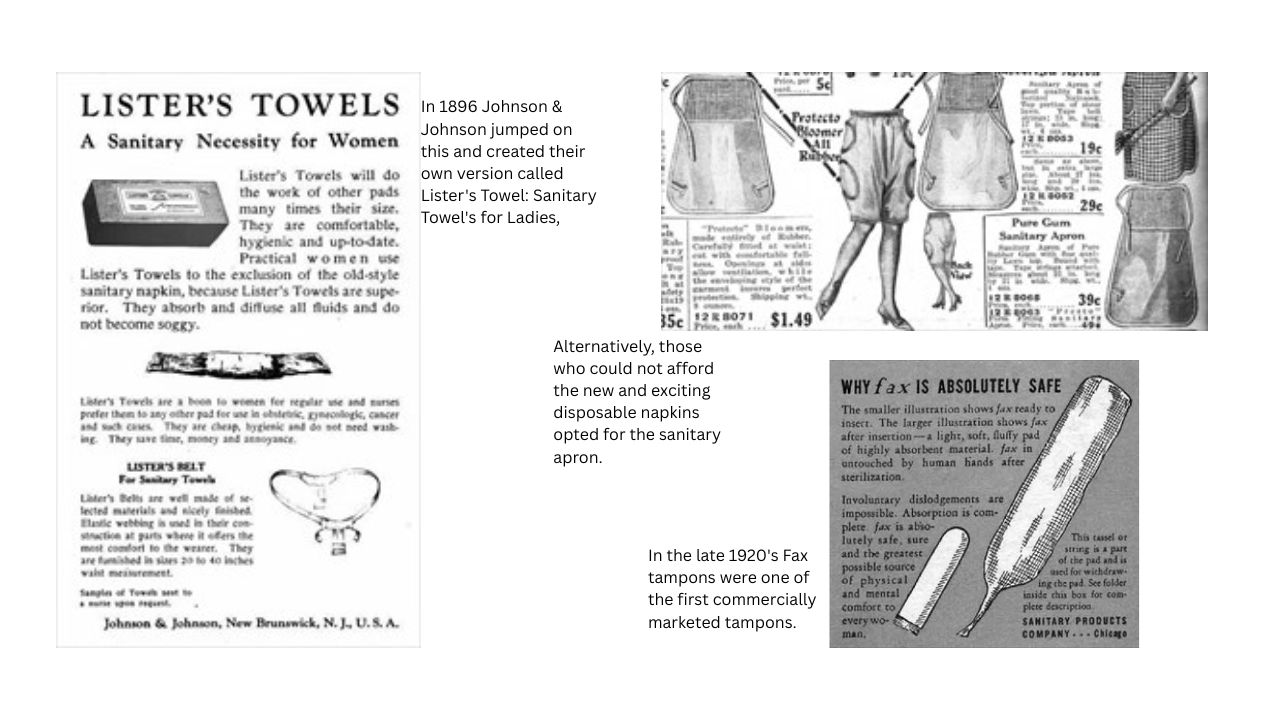

In 1896, Johnson & Johnson launched Lister’s Towels, the first disposable sanitary napkins. But cultural stigma around menstruation kept them from selling well; women were reluctant to ask for them in stores.

Early 20th Century: From Warfront to Women’s Needs

World War I brought an unexpected breakthrough. Nurses discovered that cellulose bandages, used to stop bleeding on the battlefield, were highly absorbent and cheap. This innovation led to the Kotex sanitary pad, marking one of the first commercially successful disposable period products.

In the 1920s, Fax tampons emerged, though still rudimentary. The most transformative moment came in 1933, when Earle Haas patented the modern tampon with an applicator. Soon after, Gertrude Tendrich, founder of Tampax, bought the patent and established the brand. Even so, tampons faced social resistance, particularly from conservative groups concerned about virginity and morality.

Mid-20th Century: Belts, Pads, and Patents

Through the mid-1900s, many women still used sanitary belts. African-American inventor Mary Kenner created an adjustable version in 1956, complete with a moisture-proof pocket. Sadly, her patent was ignored for decades due to racial discrimination.

In the 1970s, beltless pads with adhesive strips revolutionized convenience. Pads now came in various sizes—mini, maxi, with or without wings. Around the same time, feminist movements advocated for reusable options like sea sponges and cloth pads as environmentally conscious alternatives.

Menstrual Cups: A Quiet Revolution

Though menstrual cups seem like a recent innovation, the first patent was filed by Leona Chalmers in 1937. Made of latex, her design didn't gain traction due to wartime material shortages and social discomfort.

It wasn’t until 2002 that the Mooncup, a reusable silicone cup, popularized the category. Founder Su Hardy promoted it as a hypoallergenic, eco-friendly product. Unlike tampons or pads, a single menstrual cup could last up to 10 years—dramatically reducing waste. Brands like Tampax followed suit with their own versions in the late 2010s, promoting sustainability.

Late 20th Century: Safety Concerns and Regulation

The rise of toxic shock syndrome (TSS) in the late 1970s, particularly linked to super-absorbent tampons, led to thousands of hospitalizations and several deaths. This public health crisis sparked stricter regulations and awareness campaigns, including the Tampon Safety Bill (1995) and the General Product Safety Regulation (2005) in the UK.

21st Century Innovations: Empowerment and Sustainability

The last two decades have ushered in a period care renaissance. There’s a growing market for organic cotton tampons and pads, biodegradable wrappers, and subscription-based period boxes. Perhaps the biggest innovation has been period panties—moisture-wicking, antimicrobial underwear that replaces pads altogether.

Modern period brands now emphasize body positivity, gender inclusivity, and sustainability. Campaigns no longer whisper "discreet protection" but proudly celebrate menstruators taking control of their health.

Despite all the progress, menstrual stigma lingers. Even in 2025, millions of girls worldwide miss school due to lack of access to period products or sanitation. In many parts of the world, conversations around menstruation remain cloaked in secrecy or shame.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited