- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

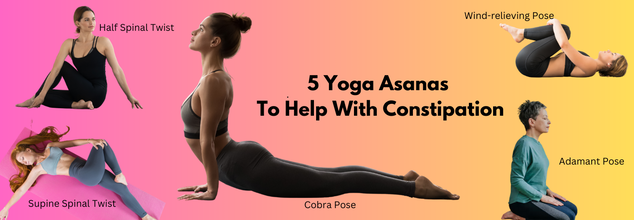

5 Yoga Poses To Relieve Your Constipation

Do you often feel constipated and have a hard time to relieve yourself? Though medications and over-the-counter treatments may look like a solution to constipation, but they are not lasting. However, yoga and certain specific asanas or poses can actually work as alternative therapies and regular practicing of the same can lead to relief for the longer run.

In fact, a 2017 study of people with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) found that yoga is helpful in reducing gastrointestinal symptoms of the condition.

Here are 5 Yoga asanas or Yoga poses that can help you with constipation:

Half Spinal Twist

- Get a mat, sit with the legs straight out in front of the body.

- Bend the right leg and place the right foot on the ground on the outside of the left leg, near the knee.

- Now, bend the left leg and place it under or close to the buttocks.

- Place the left hand or elbow on or over the right knee and gently twist to face over the right shoulder.

- You can hold this pose for few breathes before switching side.

Supine Spinal Twist

- Lie flat on your back

- Bring the arms out to the side in a 'T-position' with your palms down.

- Bend one leg at the knee.

- While you keep your shoulder flats, let the bent leg drop over the right leg.

- Hold the pose for few breaths, before switching positions.

Cobra Pose

- Start with lying flat on the stomach with the tops of the feet against the floor.

- Place your palms on the floor at the sides, underneath the shoulders. Keep the elbows tucked in against the sides of the ribcage.

- Engage your abdominal muscles and legs.

- Press the palms into the floor and life your shoulders and upper body up.

- Hold this pose for several breaths.

- Now, release and bring your body back to the floor. Repeat.

Wind-relieving Pose

This is a beginner-friendly pose and helps relieve gas that is associated with constipation.

- Lie on your back with your knees pulled up toward the chest.

- Place your hands on or around the shins.

- Tuck the chin in and press the back into the floor. Pull your knees towards the chest.

- Hold for a few breaths and release. Repeat.

Adamant Pose

- Kneel on the yoga mat with knees and toes touching the heels apart.

- Sit in the gap between the heels.

- Straighten the back and place your hands on the lap.

- Hold this pose for a few seconds to a few minutes.

Your Workout Is Reprogramming Your Gut, Here’s How Exercise Intensity Changes Everything

Credits: iStock

We've all understood that exercise improves cardiovascular function, boosts the brain, and even lifts mood but the connection between physical training and gut health is now proving to be one of the most exciting areas of medical science. New research from Edith Cowan University (ECU) in Perth, Australia, indicates that the intensity of your training—rather than the frequency—can actually reconfigure your gut microbiome in tangible ways.

PhD student Bronwen Charlesson, who headed the research, was curious to know how various training loads affect athletes' gut microbes and how these changes may reflect on health and performance. "Athletes possess a distinct gut microbiota compared with the general population," she said. "This encompasses higher total short-chain fatty acid levels, increased diversity, and a distinct balance of bacterial species.

Her research stands on the shoulders of a burgeoning body of science associating the gut microbiome with virtually every element of human health, ranging from immunity and inflammation to energy metabolism. Exercise intensity is now potentially joining diet and genes as a critical player in this intricate system.

Charlesson's work demonstrated that training intensity had a direct impact on gut health markers, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—molecule-significant compounds found when gut bacteria ferment food fiber. SCFAs are associated with decreased inflammation, better metabolic markers, and more efficient energy use and thus of interest especially for athletes.

Surprisingly, changes in the populations of some bacterial species reflected variation in training load. When doing high-intensity exercise, the gut ecosystem seemed to favor bacteria that subsist on lactate. Lactate, famously known to accompany sore muscles, doesn't only build up in the body—it's also shipped off to the gut, where certain microbes use it for energy. This gut-lactate dynamics might partially account for why athletic microbiomes differ from those of sedentary humans.

Can Rest Days Backfire on Your Gut?

The research also pointed out a behavioral twist, when training intensity decreased, diet quality also took a hit. Athletes in lower-load or rest phases had a higher tendency to eat more fast food, processed snacks, and alcohol while reducing fresh produce.

"While overall carbohydrate and fiber consumption remained constant, the food quality overall decreased," Charlesson observed. "This was accompanied by alterations in the microbiome, including decreases in protective bacteria."

Rest periods also introduced yet another change—reduced gut transit times. Basically, food moved more slowly through the digestive system, something that can shift the microbial balance. The slowing of the gut could possibly permit some bacteria to dominate and compromise the resilience gained through increased training loads.

What Does It Mean for the Athlete and Individuals That Exercise Every Day?

The results hold compelling potential for maximizing performance by managing the microbiome. Although researchers are still putting together the puzzle of exactly how the gut affects strength, endurance, and recovery, there are some theories making the rounds.

One hypothesis is that the microbiome regulates lactate metabolism and pH homeostasis, both important in explosive sports. Another is that gut bacteria are involved in nutrient uptake and energy supply, and thus diet-microbiome-exercise interaction is a three-way puzzle athletes cannot leave unsolved.

But the effects reach farther than high-end athletes. For anyone who exercises—whether you're a CrossFit enthusiast or a weekend jogger—your gut might be adjusting to how you exercise. High-intensity exercise, paired with balanced eating, may help maintain a healthier, more diverse microbiome. On the other hand, skimping on eating during recovery time could eliminate some of the benefits.

The research comes at a time when gut health is a global hot button. Digestive disorder, autoimmune, and metabolic disease rates are on the rise, and numerous researchers are looking to the microbiome as a unifying strand. Discovering how habits such as exercise intensity affect gut bacteria might be the key to new prevention and treatment avenues.

Gut health is not all about steering clear of stomach issues," Charlesson said. "It might also have a role in mental wellbeing, the immune system, and even our reaction to training. That makes it an important area to concentrate on not just for athletes but for anyone who wants to see general well-being."

How To Make Your Gut A Training Partner?

What this study actually implies is that the gut is not a passive commuter—it's an active partner in the way the body interacts with physical stress. Just as athletes dial in training phases, sleep, and water intake, the gut might have a place in the performance playbook.

Future studies might consider whether the personalization of diets based on training intensity augments both microbial diversity and athletic performance. Might probiotic or prebiotic supplementation be periodized similarly to workout routines? Might gut transit times be a signifier of recovery requirements? These are only just beginning to be queried.

Though the research was conducted on athletes, its messages have far-reaching applications. All exercisers might want to pay closer attention to how their rest days influence not just their calorie load, but also their gut flora. It's a wake-up call that health isn't an isolated thing—exercise, nutrition, and recovery are highly interdependent.

High-intensity exercise seems to make the microbiome richer in a way that might augment resilience, energy metabolism, and recovery. Consequently, a healthier gut might enable athletes—and normal exercisers—to handle higher training loads with less fatigue.

This cycle can partially account for why some people appear to thrive on strenuous regimens and others battle with chronic burnout. If subsequent studies validate this bidirectional relationship, microbiome analysis would become as ubiquitous as VO2 max or lactate threshold testing in the training room.

Why “No Time, I'm Very Busy” Is A Poor Excuse For Not Exercising, Here’s The Scientific Proof

Credits: iStock

We all know someone who swears by their morning coffee, a daily multivitamin, or even meditation as a health booster but what studies have relentlessly demonstrated is that there exists one friend that never disappoints, physical activity. Exercise is not merely a way of life—it is a well-documented defense mechanism, with the body and mind being protected from a host of chronic conditions while also encouraging longevity and life quality.

From stronger hearts and bones to sharper minds, the benefits of regular exercise are hard to overstate. And yet, despite overwhelming evidence, inactivity remains one of the leading contributors to disease and decline, particularly among older adults.

Decades of study confirm one thing: exercise is medicine. The CDC observes that older adults who exercise regularly decrease their chances of falls, lower their burden of chronic disease, and even have lower mortality rates. Beyond the body, exercise is good for mental health, delays the onset of dementia, and increases wellbeing overall.

Initiatives such as Exercise Is Medicine (EIM) Active Aging are making these findings real. Physicians are now being educated to prescribe exercise as a regular part of treatment, using instruments such as the Physical Activity Vital Sign (PAVS) to screen for inactivity before it becomes a real problem.

A new 2025 study emphasizes that even when science is unequivocal, practical impediments can stand in the way of exercise becoming an integral part of usual care. Wingood and colleagues created a step-by-step Physical Activity (PA) pathway for therapists who work with older adults. Time pressures, knowledge gaps, and burdensome electronic health records were concerns that at first seemed overwhelming. More than 88% of participating therapists, however, found the pathway practical and useful, illustrating how organized guidance can convert scientific information into actual outcomes.

This strategy is replicated across the world. In Dubai, the "Dubai Will Remain Young" initiative helps people above 60 engage in physical and social activities, balancing fitness and social integration to improve well-being. Likewise, in the United States, the Senate's 2025 hearings on sports medicine reiterated that initiatives such as EIM Active Aging are building a future where organized exercise becomes as much a part of our health habits as regular check-ups.

One of the biggest barriers to exercising with older adults is the attitude that it's hard, time-consuming, or dangerous. The truth is exactly the opposite: greater frequency and intensity of physical activity are associated with improved health outcomes across several fronts, from cardiovascular function to cognitive function. When physical therapists work together with exercise professionals, older adults can trade in sedentary lifestyle for active independence—independence that comes with confidence, mobility, and social interaction that exercise naturally fosters.

As one observer noted, "Travel is changing, and now it is no longer merely a matter of checking off places — it's about what the trip stirs in us. There's an evident shift, as increasingly more travelers look for something more, many are looking for emotional resonance, personal significance, and even healing." Likewise, exercise is no longer peripheral or optional—it's at the heart of wellbeing and longevity.

A Simple Workout Routine to Get Started

Even if you feel you don't have time, small, organized routines can help:

Warm-up (5 minutes): Light marching in place, gentle stretching, or light walking.

Strength training (10–15 minutes, 2–3 times a week):

Bodyweight squats (2 sets of 10–15 reps)

Wall push-ups (2 sets of 10–12 reps)

Seated leg lifts (2 sets of 10–12 reps per leg)

Cardio (10–20 minutes, 3–5 times a week):

Brisk walking, cycling, swimming, or climbing stairs

Flexibility & balance (5–10 minutes per day):

Yoga stretches or tai chi

Walking heel-to-toe for balance

Cool-down (5 minutes): Light stretching, deep breathing, or slow walking

Even brief periods matter. What does is regularity, progressive increase in intensity and variety to keep it interesting and effective.

Exercise is medicine- age, lifestyle, or hectic schedule is no reason. With disciplined methods, assistance by professionals, and dedication to small but regular activity, seniors and adults can change health results, avoid disease, and enhance mental health. Physical activity is not an add-on to healthcare—it is basic, integral, and revolutionary.

AIIMS Gut Doctor Shares 'Japanese Walking' Trend Just For 30 Minutes Could Help Lower Blood Pressure

(Credit-Canva)

Recently a new fitness trend has gained traction on the internet, and many people are sharing their experience trying it.

For many years, we’ve been told that a goal of walking 10,000 steps every day is a great way to stay healthy. This daily habit has been linked to a number of benefits, from reducing the risk of serious illnesses like dementia and heart disease to simply making you feel better mentally.

Japanese walking trend has gained the attention of many people including healthcare professionals. It is a new, more efficient walking technique that can give you even more health benefits without requiring as much time. This method, called interval walking, was developed in Japan and is quickly becoming a popular alternative for people looking to improve their fitness.

In a new video, Gastroenterologist Saurabh Sethi MD, shared how this walking trend could be the best thing for your gut health.

How To Do Japanese Interval Walking?

This simple and effective method was created in Japan and is based on a smart idea: mixing up your walking speed. Instead of walking at the same pace all the time, you alternate between slow and fast. Here is the simple routine:

Start with a Warm-up

Before you begin, walk at a relaxed, comfortable pace for 3 to 5 minutes. This is a crucial first step. Think of it as waking up your muscles and preparing your body for the workout ahead. A good warm-up helps prevent injuries and makes the rest of your walk more effective.

Alternate Your Pace

This is the main part of the workout. You'll switch back and forth between two different speeds. First, walk for 3 minutes at a slow, easy pace. This should feel relaxed, like a leisurely stroll. After that, switch to a brisk, fast pace for the next 3 minutes. This is where you should feel like you're in a hurry, as if you're rushing to an important meeting. This faster pace gets your heart pumping and makes the exercise more intense.

Repeat

Keep alternating between those 3-minute slow and 3-minute brisk intervals. Do this until you have completed a total of 30 minutes of walking. This simple repetition is what makes the workout so effective. It challenges your body in a way that a steady-paced walk doesn't.

End with a Cool-down

Once you've finished the 30-minute main part, slow down to a gentle, easy pace again for 3 to 5 minutes. This cool-down period helps your heart rate and breathing return to normal safely. It also helps your muscles relax, which can prevent soreness later on.

What are The Benefits of Interval Walking

This method is more than just a different way to walk; it's a smart workout. Studies have shown that because you're challenging your body with bursts of faster walking, you get a lot of great health results. Here’s what this technique can do for you:

Improve Your Heart Health

When you change speeds, you make your heart work harder and then allow it to relax. This is excellent training for your cardiovascular system, which is what keeps your heart and blood vessels healthy. The result is a stronger heart and better overall fitness.

Lower Your Blood Pressure and Stroke Risk

Regularly doing interval walking can help bring down high blood pressure. Since high blood pressure is a major risk factor for strokes, this simple routine can significantly reduce your chances of having one.

Boost Your Mood and Immune System

Physical activity helps your body release chemicals that make you feel good and happy. The varied pace of interval walking also helps strengthen your body's natural defenses, making you less likely to get sick.

Get Better Sleep

When you get enough physical activity, you use up energy and help your body wind down. The workout you get from interval walking can help you fall asleep faster and get more deep, restful sleep.

Easy on the Joints and Saves Time

Because you're not constantly walking at a high speed, this method is gentle on your joints. And since you can get all of these amazing benefits in just 30 minutes, it's a very efficient way to fit exercise into a busy schedule.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited