- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

A Genetic Disorder Caused This Indonesian Tribe To Have Sparkling Blue Eyes

Credits: Instagram - Korchnoi Pasaribu

Some people get enticed by color of eyes. While it is true that eye color may interest some people, there exists an entire tribe who have a remarkably strange eye color. This is the Buton tribe of Indonesia who have sparkling blue eyes.

This tribe is located in the southeast Sulawesi region of Indonesia. Ever since a photo taken by geologist and photographer Korchnoi Pasaribu went viral on social media, more and more people got interested to know how people can be born with natural sparkling blue eyes.

Upon researching, it has been revealed that this eye color exists due to a rare genetic disorder called Waardenburg Syndrome. This causes congenital hearing loss and pigmentation deficiencies, which can turn your eyes bright blue. It can also create a white forelock, or patches of light skin. Often times, you can have one blue eye, while your other eye is brown.

What Is Waardenburg Syndrome?

As per the National Library of Medicine's published study, Waardenburg Syndrome is a group of genetic conditions caused by mutations in genes that disrupt the migration and division of neural crest cells.

Waardenburg syndrome involves varying degrees of congenital sensorineural hearing loss along with pigmentation abnormalities. It is divided into four types, each with unique clinical features and genetic mutations. A family history of the condition is a key risk factor, as it follows autosomal dominant or, in some subtypes, autosomal recessive inheritance patterns.

Types of Waardenburg Syndrome:

Type I (WS1): Characterized by distinctive facial features, including dystopia canthorum (wide spacing between the inner corners of the eyes). It is caused by mutations in the PAX3 gene.

Type II (WS2): Similar to WS1 but without dystopia canthorum. It can be caused by mutations in different genes, such as MITF or SNAI2.

Type III (WS3): Also known as Klein-Waardenburg syndrome, this type includes the features of WS1 along with abnormalities of the arms and hands (upper limb malformations). It is also linked to PAX3 mutations.

Type IV (WS4): Known as Waardenburg-Hirschsprung disease, this form combines typical WS features with Hirschsprung disease—a condition affecting the large intestine due to missing nerve cells in the bowel wall. Mutations in genes like EDNRB, EDN3, or SOX10 are involved.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Waardenburg syndrome is diagnosed through clinical evaluation, supported by hearing tests and, when possible, molecular genetic analysis. Management involves early hearing rehabilitation, regular eye checkups, and cosmetic support for pigmentation changes. Prognosis varies with the type and severity, but with timely intervention, most individuals can expect normal development and life expectancy.

Is It Hereditary?

Most people diagnosed with this condition usually inherit it from one parent who passes a copy of mutated gene to their child during conception (autosomal dominant).

However, if an entire tribe has the similar genetic disorder, the changes are endogamous marriages and inherited Waardenburg syndrome type II and type IV in an autosomal recessive pattern, which occurs when both parents pass a copy of the mutated gene to their child during conception.

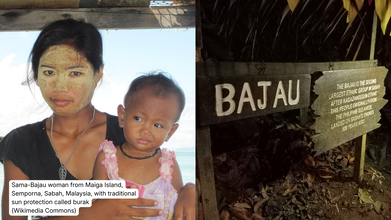

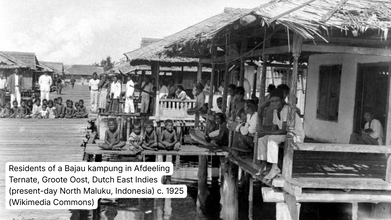

How The Buajau Sea Nomads Evolved Beyond Human Limits

Credits: Wikimedia Commons

Bajau Sea Nomads have evolved beyond human limits. But how is that even possible? Remember Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection? The survival of the fittest? This is what kept the Bajau Sea Noamds going, and evolving.

The Bajau people are sea nomads who survive by collecting shellfish from the sea floor. They come from South-East Asia, and study shows that they have developed bigger spleen for diving. They are known as 'Sea Gypsies' and are known to hold their breath for over five minutes, whereas highly trained professionals can hardly hold their breath for three to four minutes. Bajau divers spend hours underwater for fishing. They are also the world's only community of self-sufficient sea nomads, reported The Guardian.

How The Bajau Sea Nomads Evolved: What Does The Study Say?

A study published in the academic journal Cell notes that the effect of their underwater lifestyle reflected on their biology. Their spleens were larger than those of other people from the region.

How The Bajau Sea Nomads Evolved: How Does A Spleen Work?

Tucked just beside the stomach, the spleen is roughly the size of a fist and usually flies under the radar. Its everyday job is to filter old red blood cells from the blood. But under the right conditions, it can also act like a built-in oxygen reserve.

This hidden ability is especially important for the Bajau people, often called “sea nomads,” who live across parts of the southern Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia. Numbering roughly a million, the Bajau have relied almost entirely on the ocean for generations.

“For possibly thousands of years, they have been living on houseboats, travelling from place to place in the waters of South-East Asia and visiting land only occasionally,” said Melissa Ilardo from the University of Copenhagen, speaking to the BBC’s Inside Science. “Everything they need, they get from the sea.”

Read: A Genetic Disorder Caused This Indonesian Tribe To Have Sparkling Blue Eyes

How The Bajau Sea Nomads Have Evolved?

The Bajau are known for their extraordinary free-diving abilities. When diving in the traditional way, they spend up to eight hours a day at sea, with around 60 percent of that time underwater. Individual dives can last anywhere from 30 seconds to several minutes, often reaching depths of more than 70 metres.

What makes this even more remarkable is the equipment. Many Bajau divers use little more than a wooden mask or simple goggles and a weight belt. No oxygen tanks, no wetsuits, no modern diving aids.

This lifestyle prompted researchers to ask whether the Bajau body has adapted over time to support such extreme breath-hold diving.

According to Dr Ilardo, the spleen was an obvious place to look. Humans, like many marine mammals, have a natural “dive response” that kicks in when we hold our breath and submerge ourselves in water, especially cold water.

“When this response is triggered, your heart rate slows down,” she explained. “Blood vessels in your arms and legs constrict to preserve oxygen-rich blood for vital organs like the brain and heart.”

The final part of this response involves the spleen.

How The Bajau Sea Nomads Evolved: An enlarged Spleen Boosts Oxygen

The spleen acts as a reservoir for oxygenated red blood cells. When it contracts during a dive, it releases these cells into the bloodstream, giving the body a temporary oxygen boost.

“It’s like a biological scuba tank,” Dr Ilardo said.

For people like the Bajau, who dive repeatedly every day, this spleen contraction can make a crucial difference, helping them stay underwater longer and recover faster between dives.

In short, what seems like an ordinary organ plays an extraordinary role, revealing how the human body can adapt in remarkable ways to extreme environments.

A Child Dies Every Nine Minutes in India From Drug Resistance, Data Shows

Credit: Canva

One child in India dies every nine minutes from an infection caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria, as it becomes one of the top 10 global public health threats, experts warn.

Dr HB Veena Kumari of the Department of Neuromicrobiology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, claims: "The Covid-19 pandemic has significantly contributed to rising antimicrobial resistance. The World Health Organisation projects that 10 million deaths will occur annually by 2025."

According to the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria in the body learns to withstand and remain unaffected by the medicines (antibiotics) meant to kill them.

In such cases, doctors have to switch to different antibiotics, but these backup medicines might not work as well or might cause more side effects. Additionally, infections may also worsen over time as bacteria can become resistant to all available drugs.

Alarmingly is that these tough, drug-resistant bacteria can spread from one person to another, both in hospitals and at home.

According to Dr TS Balganesh, Gangagen Biotechnologies, nearly 36 percent of haemodialysis patients die from fatal infections, which is second only to cardiovascular diseases as a cause of death.

He tells Deccan Herald: "The risk for infective endocarditis in haemodialysis patients is approximately 18 times higher than in the general population and up to 58 percent of these episodes are caused by a bacteria named 'S aureus', with an in-hospital mortality of more than 50 percent."

What Does WHO Say?

One out of every six serious infections confirmed in labs worldwide last year could not be killed by the antibiotics meant to treat them.

Between 2018 and 2023, the problem of antibiotics failing (called resistance) got much worse. For many common types of germs, resistance went up by 5% to 15% every year. The growing inability of these essential medicines to work is a huge threat to people everywhere.

Which Antibiotics Are People Becoming Resistant To?

The WHO's latest report is the most detailed look yet at this issue. It reports on how much resistance exists across 22 different antibiotics, which include common drugs used to treat everyday illnesses. The report focused on eight common types of bacteria that cause things like:

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs)

- Stomach and intestinal infections

- Dangerous blood infections

- Gonorrhoea

Additionally, Dr Obaidur Rahman of Dr Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital has also warned that the country’s casual use of Azithromycin, sold under brand names such as Zithromax, Azee and Zmax, has worsened its effectiveness and pushed India closer to a major public health challenge.

A drug often prescribed for sore throats and upper respiratory tract infections, Dr Rahman noted that Azithromycin was once effective against Mycoplasma Pneumonia, a bacterium responsible for pneumonia in adults and children.

READ MORE: India’s New Antibiotic in 30 Years Offers Hope Against Antibacterial-Resistant Infections

However, this is no longer the case as India now shows an alarming 80 to 90 percent resistance to the drug when treating infections caused by this bacterium. A medicine that once addressed a wide range of respiratory problems is no longer reliable for many patients.

The surgeon has since urged people to avoid taking antibiotics without proper medical advice. Most seasonal respiratory infections resolve on their own, and unnecessary drugs only add to the resistance problem.

Supreme Court Declares Menstrual Hygiene As Part Of Right To Life; Free Sanitary Pads For Girls In All Schools

Credits: Britannica and Canva

Supreme Court on Friday declared the right to menstrual health as part of the right to life under Article 21 of the Constitution. The court issued a slew of directions to ensure that every school provides biodegradable sanitary napkins free of cost to adolescent girls. The guidelines also ensured that schools must be equipped with functional and hygienic gender-segregated toilets. The Court directed the pan-India implementation of the Union's national policy, 'Menstrual Hygiene Policy for School-going Girls' in schools for adolescent girl children from Classes 6-12.

Read: Menopause Clinics Explained: Latest Launch By Maharashtra And Kerala Government

Supreme Court Declares Menstrual Hygiene As Part Of Right To Life: Here Are the Directions

A bench comprising Justice JB Pardiwala and Justice R Mahadevan passed the following directions:

- All States/UT must ensure that every school, whether government-run or privately managed, in both urban and rural areas, is provided with functional gender segregated toilets with usable water connectivity.

- All existing or newly constructed toilets in schools shall be designed, constructed and maintained to ensure privacy and accessibility, including by catering to needs of children with disabilities.

- All school toilets must be equipped with functional washing facilities and soap and water available at all times.

- All states/UTs must ensure that every school, whether government-run or privately managed, in both urban and rural areas, provide oxo-biodegradable sanitary napkins manufactured in compliance with the ASTM D-6954 standards free of cost. Such sanitary napkins must be made readily accessible to girl students, preferably within toilet premises through sanitary napkin vending machines or, where not visible, at a designated place.

- All States/UTs must ensure that every school, whether government-run or privately managed, in both urban and rural areas establish menstrual hygiene management corners. It must be equipped with spare innerwears, uniforms, disposable pads and other necessary materials to address menstrual urgency.

The court also issued directions for the disposal of sanitary waste. Justice Pardiwala said, "This pronouncement is not just for stakeholders of the legal system. It is also meant for classrooms where girls hesitate to ask for help. It is for teachers who want to help but are restrained due to a lack of resources. And it is for parents who may not realise the impact of their silence and for society to establish its progress as a measure in how we protect the most vulnerable. We wish to communicate to every girlchild who may have become a victim of absenteeism because her body was perceived as a burden when the fault is not hers."

Read: Menstrual Cups To Replace Sanitary Napkins In Karnataka Government Schools

Why Is This Judgment So Important?

In India, menstruation is still seen as taboo. In fact, there is a lot of shame around it. Menstrual shame is the deeply internalized stigma, embarrassment, and negative perception surrounding menstruation, which causes individuals to feel unclean, or "less than" for a natural biological process. This judgment thus is an effort to do away with the shame rooted in cultural, social, and religious taboos, which is often the reason why many girls drop out, or due to lack of awareness, develop health adversities.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited