- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Medical Memoir: The History Of Period Care Through Years Of Menstrual Products' Evolution

Credits: Canva

'Medical Memoir' is a Health & Me series that delves into some of the most intriguing medical histories and unveils how medical innovations have evolved over time. Here, we trace the early stages of all things health, whether a vaccine, a treatment, a pill, or a cure.

Menstrual products have come a long way—from homemade cloth rags and belts to silicone menstrual cups and sleek, leak-proof underwear. The history of these products is as much about medical innovation as it is about cultural taboos, social shifts, and gendered marketing. While nearly half the world menstruates at some point, the journey toward safer, dignified, and sustainable period care has been anything but straightforward.

Ancient Origins: Creativity and Cultural Beliefs

Long before commercial products existed, women relied on locally available materials. In ancient Greece, tampon-like devices were reportedly made using lint wrapped around light wood. Egyptian women fashioned internal devices from softened papyrus, while Roman women used wool or cotton pads secured with belts. Meanwhile, Native American women used moss and buffalo skin, and in Equatorial Africa, grass rolls absorbed menstrual blood.

Also Read: Shubhanshu Shukla Returns From ISS, What All Medical Examinations Are Lined Up

However, these were not necessarily used openly. Menstruation was frequently wrapped in superstition and shame. Ancient texts reveal contradictory beliefs: while Egyptian medical papyri regarded menstrual blood as medicinal, Roman and early Christian texts often considered it impure, even dangerous.

19th Century: Cloth Pads and the Birth of Sanitary Belts

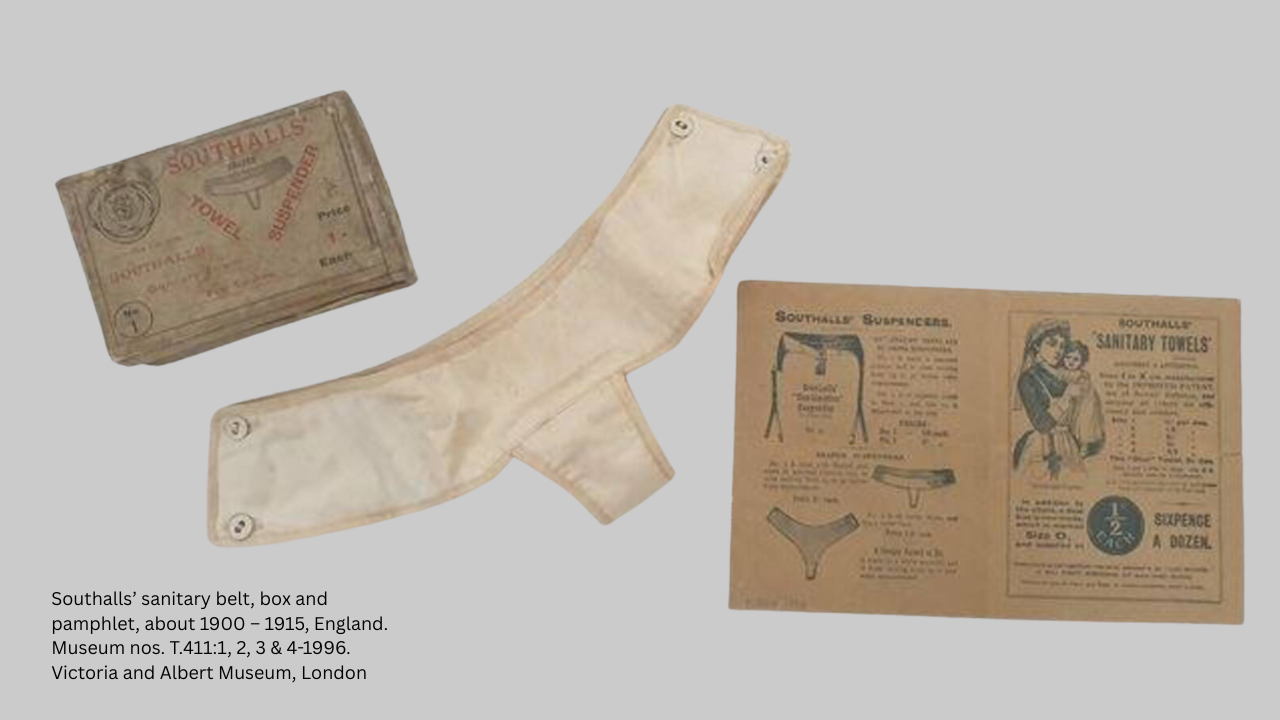

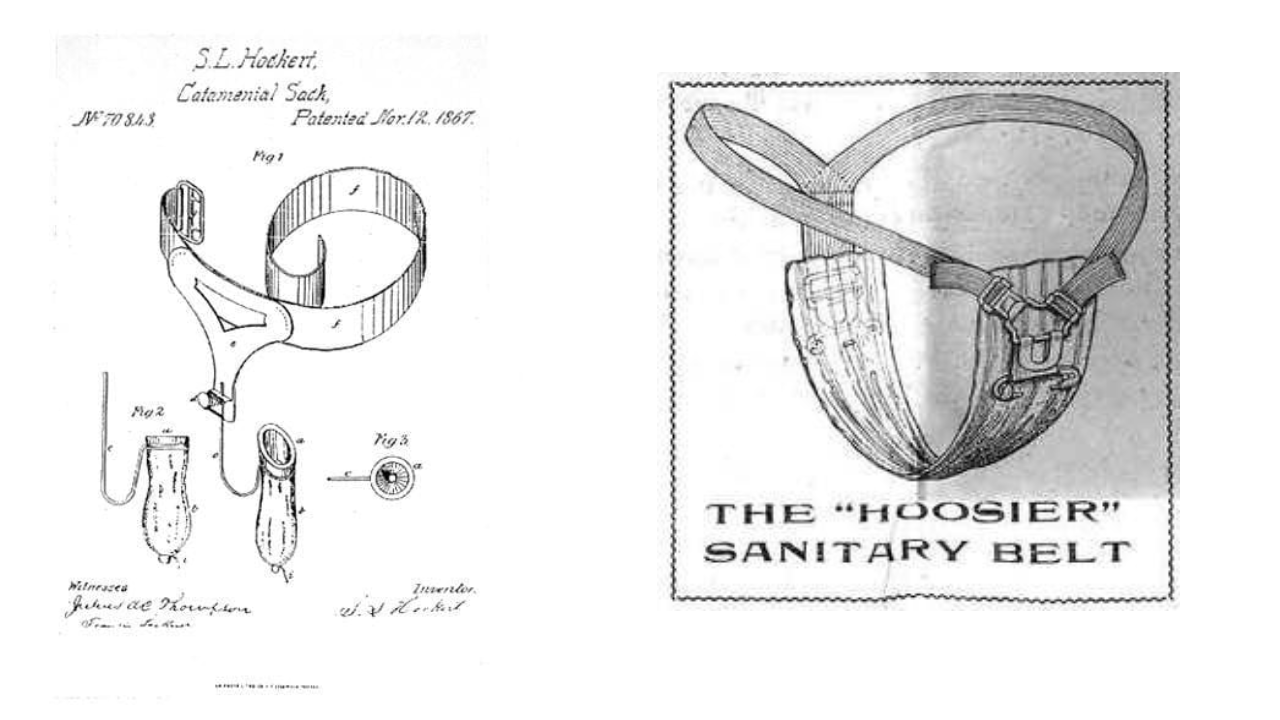

By the 1800s, European and American women commonly used reusable cloth rags made from flannel or linen. These were washed and reused but posed hygiene concerns. The late 19th century saw the invention of the sanitary belt—a strap-on belt that held a pad in place. Brands like Southalls’ Shaped Towel Suspender marketed these belts for women “travelling by land or sea.”

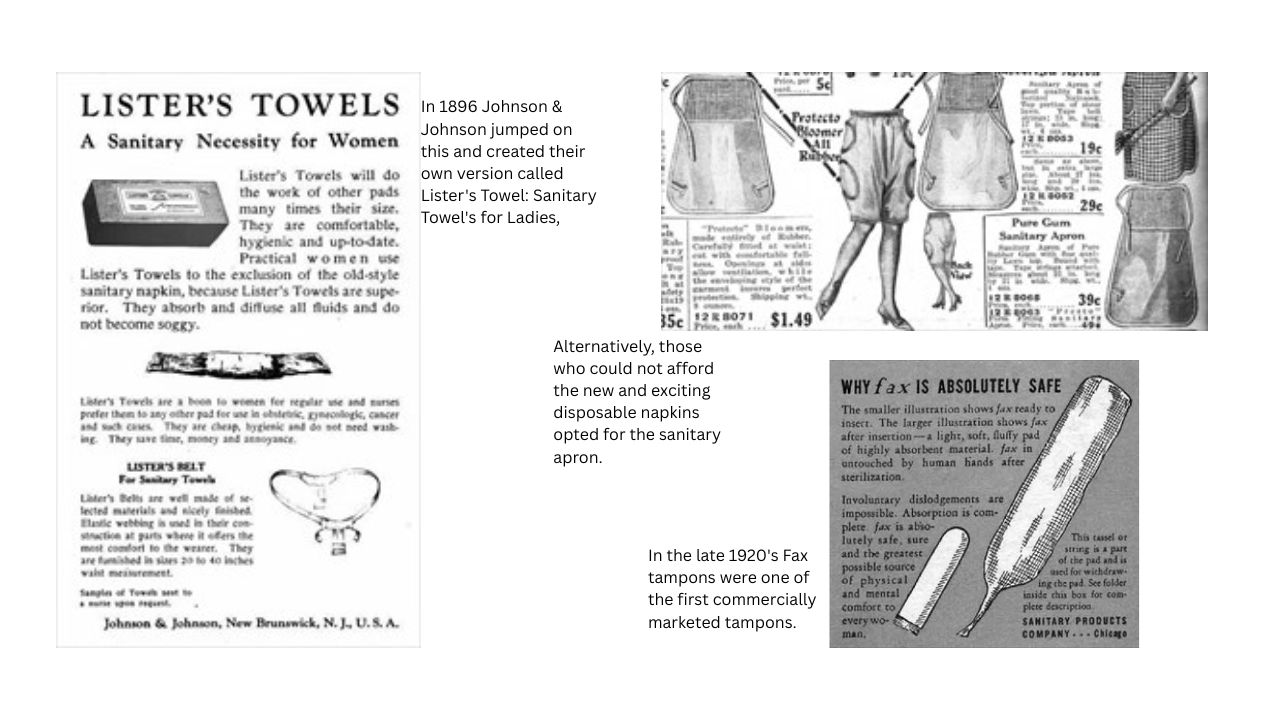

In 1896, Johnson & Johnson launched Lister’s Towels, the first disposable sanitary napkins. But cultural stigma around menstruation kept them from selling well; women were reluctant to ask for them in stores.

Early 20th Century: From Warfront to Women’s Needs

World War I brought an unexpected breakthrough. Nurses discovered that cellulose bandages, used to stop bleeding on the battlefield, were highly absorbent and cheap. This innovation led to the Kotex sanitary pad, marking one of the first commercially successful disposable period products.

In the 1920s, Fax tampons emerged, though still rudimentary. The most transformative moment came in 1933, when Earle Haas patented the modern tampon with an applicator. Soon after, Gertrude Tendrich, founder of Tampax, bought the patent and established the brand. Even so, tampons faced social resistance, particularly from conservative groups concerned about virginity and morality.

Mid-20th Century: Belts, Pads, and Patents

Through the mid-1900s, many women still used sanitary belts. African-American inventor Mary Kenner created an adjustable version in 1956, complete with a moisture-proof pocket. Sadly, her patent was ignored for decades due to racial discrimination.

In the 1970s, beltless pads with adhesive strips revolutionized convenience. Pads now came in various sizes—mini, maxi, with or without wings. Around the same time, feminist movements advocated for reusable options like sea sponges and cloth pads as environmentally conscious alternatives.

Menstrual Cups: A Quiet Revolution

Though menstrual cups seem like a recent innovation, the first patent was filed by Leona Chalmers in 1937. Made of latex, her design didn't gain traction due to wartime material shortages and social discomfort.

It wasn’t until 2002 that the Mooncup, a reusable silicone cup, popularized the category. Founder Su Hardy promoted it as a hypoallergenic, eco-friendly product. Unlike tampons or pads, a single menstrual cup could last up to 10 years—dramatically reducing waste. Brands like Tampax followed suit with their own versions in the late 2010s, promoting sustainability.

Late 20th Century: Safety Concerns and Regulation

The rise of toxic shock syndrome (TSS) in the late 1970s, particularly linked to super-absorbent tampons, led to thousands of hospitalizations and several deaths. This public health crisis sparked stricter regulations and awareness campaigns, including the Tampon Safety Bill (1995) and the General Product Safety Regulation (2005) in the UK.

21st Century Innovations: Empowerment and Sustainability

The last two decades have ushered in a period care renaissance. There’s a growing market for organic cotton tampons and pads, biodegradable wrappers, and subscription-based period boxes. Perhaps the biggest innovation has been period panties—moisture-wicking, antimicrobial underwear that replaces pads altogether.

Modern period brands now emphasize body positivity, gender inclusivity, and sustainability. Campaigns no longer whisper "discreet protection" but proudly celebrate menstruators taking control of their health.

Despite all the progress, menstrual stigma lingers. Even in 2025, millions of girls worldwide miss school due to lack of access to period products or sanitation. In many parts of the world, conversations around menstruation remain cloaked in secrecy or shame.

Men Lose Their Y Chromosomes As They Age, Here's Why It Matters

Credits: Canva

For decades, scientists believed the gradual loss of the Y chromosome in ageing men did not matter much. But a growing body of research now suggests otherwise. Studies show that losing the Y chromosome in blood and other tissues is linked to heart disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease and even shorter lifespan. The crux is simple but striking. As men age, many of their cells quietly lose the Y chromosome, and this loss may be shaping men’s health in ways we are only beginning to understand.

Aging And The Disappearing Y Chromosome

Men are born with one X and one Y chromosome. While the X carries hundreds of important genes, the Y is much smaller and contains just 51 protein coding genes. Because of this, scientists long assumed that losing the Y in some cells would not have serious consequences beyond reproduction.

However, newer genetic detection techniques tell a different story. Research shows that about 40 percent of men aged 60 have some cells that have lost the Y chromosome. By age 90, that number rises to 57 percent. Smoking and exposure to carcinogens appear to increase the likelihood of this loss.

This phenomenon, known as mosaic loss of Y, does not occur in every cell. Instead, it creates a patchwork in the body where some cells carry the Y chromosome and others do not. Once a cell loses the Y, its daughter cells also lack it. Interestingly, Y deficient cells seem to grow faster in laboratory settings, which may give them a competitive edge in tissues and even in tumors.

Why Would Losing The Y Matter?

The Y chromosome has long been viewed as mainly responsible for male sex determination and sperm production. It is also uniquely vulnerable during cell division and can be accidentally left behind and lost. Since cells can survive without it, researchers assumed it had little impact on overall health.

Yet mounting evidence challenges that assumption. Several large studies have found strong associations between loss of the Y chromosome and serious health conditions in older men. A major German study reported that men over 60 with higher levels of Y loss had an increased risk of heart attacks. Other research links Y loss to kidney disease, certain cancers and poorer cancer outcomes.

There is also evidence connecting Y loss with neurodegenerative conditions. Studies have observed a much higher frequency of Y chromosome loss in men with Alzheimer’s disease. During the COVID pandemic, researchers noted that men with Y loss appeared to have worse outcomes, raising questions about its role in immune function.

Is Y Loss Causing Disease?

Association does not automatically mean causation. It is possible that chronic illness or rapid cell turnover contributes to Y loss rather than the other way around. Some genetic studies suggest that susceptibility to losing the Y chromosome is partly inherited and tied to genes involved in cell cycle regulation and cancer risk.

However, animal research offers stronger clues. In one mouse study, scientists transplanted Y deficient blood cells into mice. The animals later developed age related problems, including weakened heart function and heart failure. This suggests the loss itself may directly contribute to disease.

A New Chapter In Men’s Health

So how can such a small chromosome have such wide ranging effects? While the Y carries relatively few genes, several of them are active in many tissues and help regulate gene activity. Some act as tumor suppressors. The Y also contains non coding genetic material that appears to influence how other genes function, including those involved in immune responses and blood cell development.

The full DNA sequence of the human Y chromosome was only completed recently. As researchers continue to decode its functions, the message for men’s health is becoming clearer. Ageing is not just about wrinkles or grey hair. At a microscopic level, the gradual disappearance of the Y chromosome may be quietly influencing heart health, brain health and cancer risk.

Understanding this process could open new doors for early detection, personalized risk assessment and targeted therapies that help men live longer and healthier lives.

Udit Narayan’s First Wife Alleges She Was Forced to Undergo Hysterectomy, Files Police Complaint

Credits: Facebook

First wife of singer Udit Narayan, Ranjana Narayan Jha made serious allegations against him, claiming that he forced her to get hysterectomy. She filed a police complaint earlier this week at the Women's Police Station in Supaul district, Bihar.

She accused Udit Narayan and his two brothers Sanjay Kumar Jha and Lalit Narayan Jha and his second wife Deepa Narayan of a criminal conspiracy that lead to hysterectomy - the surgical removal of uterus, without her knowledge. As per an NDTV report, "She claimed she became aware of this only years later during medical treatment."

Udit Narayan's First Wife's Allegations

As per the complaint, Udit and Ranjana were married on December 7, 1984, in a traditional Hindu ceremony. Udit then moved to Mumbai in 1985 to pursue his music career. She later learned through media that he had married another woman Deepa. As per the complaint, he continued to mislead her whenever she confronted him.

As per the complaint, in 1996, she was taken to a hospital in Delhi under the pretext of medical treatment, where, she claims that her uterus was removed without her knowledge. She said that she was compelled to file a complaint years after being ignored. "You all know that Udit Narayan ji repeatedly makes promises but does not fulfill them. He has not done anything till now, which is why I have come to the Women's Police Station. I deserve justice," she said.

"Nowadays, I am constantly unwell and need his support. But Udit Narayan is neither saying anything nor doing anything. He came to the village recently and left after making promises once again," she said, as per a Hindustan Times report.

What Is Hysterectomy?

It is the surgical removal of one's uterus and cervix. There are different kinds of hysterectomy available, which depends on the condition of the patients.

Total Hysterectomy

This removes uterus and cervix, but leaves ovaries. This means the person does not enter menopause after the surgery.

Supracervical Hysterectomy

Removing just the upper part of the uterus and leaving the cervix. This could also be when your fallopian tubes and ovaries are removed at the same time. Since, you have a cervix, you will still need Pap smears.

Total Hysterectomy With Bilateral Salpingo-oophorectomy

This is the removal of uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes and ovaries. This will start menopause immediately after the surgery.

Radical Hysterectomy With Bilateral Salpingo-oophorectomy

This is the removal of uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes, ovaries, the upper portion of your vagina, and some surrounding tissue and lymph nodes. This is done to people with cancer. Patients who get this enter menopause right after the surgery.

Lorna Luxe's Husband John Dies After Three Year Long Cancer Battle

Credits: Instagram

Lorna Luxe's Husband, 64, John Andrews passed away after a three-year-long cancer battle. On February 11, the British influencer shared a post on her Instagram. The 43-year-old wrote: "My beautiful, brave John died yesterday. I am heartbroken. We were together to the every end, at home, in our own bed and holding hands which is exactly what he wanted."

Lorna Luxe's Husband John Dies: What Happened To Him?

John, a former banker, was diagnosed with stage three cancer in 2023. He had been receiving treatment over the last three years. John's cancer also entered remission and it returned in 2024 and spread to his brain.

He underwent a surgery in 2025, however, he was back in hospital in December after a complication with his chemotherapy treatments. This led to organ failure.

In January this year, Lorna told her followers that she was "looking for a miracle" and shared that his cancer had "progressed to his other organs" and treatment was "no longer an option".

“I think he's possibly the bravest person. And I suppose at this point we're looking for a bit of a miracle and we're going to take each day as it comes,” she wrote on her post.

In her post that announced John's death, she wrote when she asked him how he was feeling, her husband responded, "Rough, but in love".

Read: Catherine O'Hara Cause Of Death Is Pulmonary Embolism; She Also Had Rectal Cancer

Lorna Luxe's Husband John Dies: Can Cancer Spread To Other Organs?

While John's cancer has not been specified, but the reports reveal that his cancer spread to other organs. According to National Institution of Health (NIH), US, the spreading of cancer to other parts of the body is called metastasis.

This happens when cancer cells break away from where they first formed, and travel through the blood or lymph system. This could lead to formation of new tumors in other parts of the body. Cancer can spread to anywhere in the body, however, it is common for cancer to move into your bones, liver, or lungs.

When these new tumors are found, they are made of the same cells from the original tumor. Which means, if someone has lung cancer and it spread to brain, the cells do not look like brain cancer. This means that the cancer cells in the brain is metastatic lung cancer.

Cancer cells could also be sent to lab to know the origin of the cell. Knowing the type of cancer helps in better treatment plan.

Lorna Luxe's Husband John Dies: Could Chemotherapy Lead To Organ Damage?

As per the University of Rochester Medical Center, in some cases, chemotherapy could cause permanent changes or damage to the heart, lungs, nerves, kidneys, and reproductive organs or other organs.

For instance, some anti-cancer drugs cause bladder irritation, it could result in temporary or permanent damage to kidneys or bladder. In other cases, chemotherapy could also have potential effects on nerves and muscles. Chemotherapy could also damage the chromosomes in the sperm, which could also lead to birth defects. In females, it could damage the ovaries and could result in short-term or long-term fertility issues.

Chemotherapy could also induce menopause before the correct age and could cause symptoms like hot flashes, dry vaginal tissues, sweating, and more.

For some, it could also cause a 'chemo-brain', which is a mental fog that many chemotherapy patients face, that could affect memory or concentration.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited