- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Do Not Give Your Kids Smartphones Until They Are This Age – Study Discourages Early Smartphone Access

(Credit-Canva)

Being a parent can be an overwhelming task, kids running amok, household chores that take hours and ensuring the safety of everyone on the home. Combining all of these and trying to do everything at once is a herculean task, too much for a person to handle. Often in these times parents are looking for easier ways to take care of everything, starting with the child. It may seem easier to hand off your smartphone to ensure your child does not run around and stays entertained for a long time, but you could be making a big mistake that will eventually cause your child harm.

A new study published in the Journal of Human Development and Capabilities found that kids who received a smartphone before age 13 generally had worse mental health and overall well-being as young adults.

Early Smartphones Linked to Poorer Mental Health

Specifically, people aged 18 to 24 who got their first smartphone at age 12 or younger were more likely to experience:

- Suicidal thoughts

- Aggression

- Feeling detached from reality

- Difficulty managing emotions

- Low self-worth

Social Media's Harmful Influence

Researchers believe that getting early access to the often-toxic world of social media explains a big part of why young smartphone users had poorer mental health. When kids are very young, their minds are still developing, making them more easily affected by negative online environments. They might not have enough real-world experience to deal with what they see or experience online. Other things that contribute to these problems include cyberbullying, disrupted sleep (because they're on their phones late), and difficulties in family relationships.

"Mind Health Quotient" Scores of 100,000 Young Adults

The study looked at data from over 100,000 young adults globally as part of the Global Mind Project. Participants completed a questionnaire to measure their Mind Health Quotient (MHQ), which assesses overall well-being.

The results showed that young adults who got their first smartphone before their teenage years had lower MHQ scores. In general, the younger a person received their first smartphone, the worse their mental health and well-being were later on.

For example, about 48% of girls who got a smartphone at age 5 or 6 reported suicidal thoughts, compared to 28% of those who got one at 13. Girls with early smartphone access also tended to have lower self-image, self-worth, confidence, and emotional resilience. Boys, on the other hand, were more likely to show lower stability, self-worth, and empathy.

Contributing Factors

The study dug deeper to find out why this link exists. They found that early access to social media explained about 40% of the connection between getting a smartphone young and having worse mental health as a young adult. Researchers suggest that the way social media apps work, especially with their AI-driven recommendations, can push harmful content and make children compare their lives to seemingly perfect influencers, which can be very damaging.

Other factors also played a role: poor family relationships accounted for 13% of the link, disrupted sleep for 12%, and cyberbullying for 10%.

Calls for Action

Based on these findings, researchers are urging leaders to take a "precautionary approach," similar to how alcohol and tobacco are regulated. They recommend:

- Restricting smartphone access for children under 13.

- Making digital literacy education mandatory.

- Holding companies accountable for the effects of their platforms.

Some countries like France, the Netherlands, Italy, and New Zealand have already banned or limited cell phone use in schools. In the U.S., several states have also passed laws to limit or ban smartphones in schools.

While the study cannot directly prove that early smartphone access causes poorer mental health, researchers emphasize that the evidence is strong enough to warrant taking preventative action now. They point out that smartphones are not the only cause of declining mental health in young adults, but they play a significant role.

Expecting Soon? These Are The 3 Common Pregnancy Complications You Must Know About

Credits: Canva

Pregnancy occurs when a sperm fertilizes an egg released during ovulation. The fertilized egg travels down the fallopian tube and attaches to the lining of the uterus, where it begins to grow. Ovulation typically occurs about 14 days before the start of the next menstrual period, making the days just before and during ovulation the most fertile window.

Experts suggest that the best time to conceive is during this fertile window, often spanning five to six days in the middle of the menstrual cycle. Factors such as age, lifestyle, medical history, and reproductive health play an important role in conception.

Once pregnancy is confirmed, ongoing medical care and regular monitoring are essential to ensure both maternal and fetal health. However, several complications may arise during pregnancy, even in otherwise healthy individuals.

Below are three common pregnancy-related complications and what to know about them.

Gestational Diabetes: Temporary but Significant Condition

What it is:

Gestational diabetes is a condition in which blood sugar levels become elevated during pregnancy. It is typically diagnosed between the 24th and 28th week of gestation and results from hormonal changes that impair the body’s ability to use insulin effectively.

Risks:

If left unmanaged, gestational diabetes can lead to several complications. These include high blood pressure during pregnancy, delivering a larger-than-average baby (macrosomia), and an increased likelihood of cesarean delivery. The baby may also face short-term issues like low blood sugar after birth and long-term risks such as obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Symptoms:

Often asymptomatic, but some individuals may notice increased thirst, frequent urination, fatigue, or nausea.

Management:

Management typically includes dietary changes, moderate physical activity, and frequent monitoring of blood glucose levels. In certain cases, insulin therapy may be required to maintain optimal blood sugar levels. Timely diagnosis and control are critical to preventing complications.

Preeclampsia: A Serious Hypertensive Disorder

What it is:

Preeclampsia is characterized by high blood pressure and signs of organ dysfunction, most commonly affecting the liver and kidneys. It generally occurs after 20 weeks of pregnancy but can also emerge in the postpartum period.

Risks:

If not treated, preeclampsia can progress to eclampsia, a condition marked by seizures. It also increases the risk of stroke, organ damage, placental abruption, and can result in preterm birth or restricted fetal growth.

Symptoms:

Signs include high blood pressure, protein in the urine, persistent headaches, visual disturbances, pain in the upper abdomen, nausea, and swelling—especially in the face and hands.

Management:

Treatment depends on the severity and the stage of pregnancy. For mild cases, blood pressure monitoring and medication may be sufficient. In more severe scenarios, early delivery may be necessary to protect the health of both mother and baby. Regular prenatal care is key for early detection.

Placenta Previa: A Structural Concern in Pregnancy

What it is:

Placenta previa occurs when the placenta partially or fully covers the cervix, which can obstruct the baby’s exit path during labor.

Risks:

This condition can lead to severe bleeding during pregnancy and delivery, potentially endangering both maternal and fetal health. It also increases the chances of preterm delivery and often requires a cesarean section.

Symptoms:

The primary symptom is painless, bright red vaginal bleeding in the second or third trimester. Some individuals may also experience mild cramps or contractions.

Management:

Management strategies depend on the extent of placental coverage and gestational age. These may include pelvic rest, reduced physical activity, hospitalization, or planned early delivery via cesarean section.

Importance of Early Monitoring

Early diagnosis and appropriate intervention can significantly reduce the risks associated with these complications. Routine prenatal checkups, diagnostic tests, and being alert to changes in the body help ensure timely management and improve outcomes for both the pregnant individual and the baby.

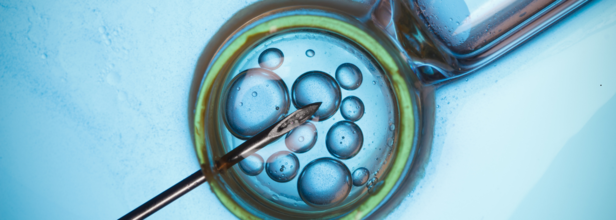

Not All Infertility Needs IVF; Sometimes, It’s The Bravest Choice You’ll Make

Credits: Canva

If you’re reading this, I imagine you’re at a difficult crossroads — waiting, wondering, perhaps even overwhelmed by words like "IVF", "hormones", or "failed cycles". And you’re not alone. As a fertility specialist, I’ve seen the fear those three letters — I-V-F — can bring. But before we go there, let me tell you something you may not hear enough: IVF is not always necessary.

In fact, more often than people realize, couples struggling to conceive may never need it at all.

When Less is More

The journey to parenthood isn’t always high-tech. Sometimes, it’s about tuning into the body’s signals, correcting what’s slightly off, and allowing nature the space to do what it’s meant to.

Here are a few examples of when IVF isn’t the first stop:

- A woman with PCOS who just needs a little help ovulating regularly

- A couple with no obvious issues, but who simply need guidance on timing or intrauterine insemination (IUI)

- A case where correcting a thyroid imbalance or removing a uterine polyp makes all the difference

- Men with slightly low sperm counts where medical therapy or IUI works beautifully

But Then There Are Times When IVF Isn’t Just Right — It’s Necessary

Let’s shift focus now — not to scare, but to clarify. Because when IVF is the right path, it can change everything.

Here’s when I don’t hesitate to recommend it:

- Blocked fallopian tubes: When sperm and egg physically cannot meet, IVF becomes the only route.

- Severe male factor: If sperm count, motility, or structure are critically low, IVF with ICSI gives even a single good sperm a chance.

- Age-related fertility decline: After 38, every month counts. IVF allows us to act quickly and, where needed, genetically screen embryos.

- Endometriosis: When pelvic inflammation or scarring stands in the way, IVF helps us bypass the barriers.

- Repeated IUI failures: After multiple well-timed IUIs without success, IVF often becomes the next logical step.

- Genetic considerations: IVF allows preimplantation testing — a game-changer for couples carrying inheritable conditions.

And then there are those who choose IVF not out of necessity, but out of foresight:

Women preserving their fertility before chemotherapy. Or professionals freezing eggs to give themselves more time. IVF, in these cases, becomes a quiet act of empowerment.

The Real Story Isn’t About Technology — It’s About Timing and Trust

I’m not here to champion or criticize any one path. I’m here to say: there’s no one-size-fits-all. IVF isn’t “last resort” medicine. Nor should it be your first panic move. It’s a tool — powerful, yes — but only as good as the hands and hearts guiding it.

So if you're considering it, or worried you might need it, don’t be afraid. Sit with someone who’ll weigh your options honestly, not push you into protocols.

Because sometimes, the strongest thing you can do — is ask for help at the right time.

Inner Child: Kids Start Judging Their Bodies Before They Can Even Spell ‘Fat’, The Damage Can Last A Lifetime

Credits: Canva

Inner Child’ is Health and Me's new mental health series where we deep dive into lesser-known aspects of child psychology and how it shapes you as you grow up. Often unheard, mistaken, and misunderstood, in this series we talk about the children’s perspective and their mental health, something different than you might have read in your parenting books. After all, parenting is not just about teaching but also unlearning.

A new study from Durham University has found that children as young as five years old begin to form their perception of what a "normal" body looks like based purely on visual exposure, and that this perception can be subtly, but powerfully, reshaped by what they repeatedly see around them.

Led by Professor Lynda Boothroyd from Durham's Department of Psychology, the study reveals that just like adults, children’s brains adapt quickly to the images they are exposed to.

In the experiment, children aged 7 to 15 were shown a series of body images and asked to rate their heaviness. After viewing either thin or heavy body types repeatedly, their perception of what was “normal” shifted.

Those who saw heavier figures began rating the same bodies as lighter than they had before — indicating that their internal “model” of a normal body had recalibrated.

This shift wasn’t limited to older children. The youngest participants, seven-year-olds, too, showed the same level of perceptual flexibility as adults.

The implications are significant: it suggests that by early primary school, and likely even before, children’s views about bodies are already being shaped by their environment, including toys, cartoons, advertisements, and even family comments.

The Seeds of Self-Image: What Shapes Children Early

Dr. Sameer Malhotra, Director and Head of the Department of Mental Health and Behavioral Sciences at Max Super Speciality Hospital, Saket, explains that children as young as three to five years old begin internalizing messages about body image, and often in ways adults may not even notice.

“Parental language plays a huge role,” he says. “When a parent casually says, ‘I feel fat today,’ or makes dieting comments, children absorb that. Even if the comment isn’t directed at them, it registers.” Children also learn by imitation. This means they pick up patterns of behavior, tone, and attitudes from parents, siblings, peers, and media.

Toys and cartoons often carry these subtle messages too.

Dolls with tiny waists, heroes with exaggerated muscles, or villains portrayed as overweight, all reinforce stereotypes.

“Children's media tends to link thinness with success, beauty, or goodness,” Malhotra adds. “These associations are laid down before a child even begins formal schooling.”

Words That Stick: The Power of Casual Comments

Even offhand remarks like “Don’t eat too much, you’ll get fat” or calling someone “too skinny” can significantly influence a child's self-image. Dr. Malhotra points out that such language can link appearance to self-worth, foster guilt around food, and create anxiety about acceptance.

“Children mirror parental opinions. If they hear fat-shaming or appearance-based criticism, they begin to judge themselves and others the same way,” he explains. And these judgments don't remain in childhood, they form the blueprint for how a person thinks about their body throughout life.

What Can Be Done?

While this conditioning starts young, it can also be gently undone. The Durham study highlights the power of simply seeing more diverse body types. According to Dr. Malhotra, both homes and schools can play a big role in broadening what “normal” looks like.

“Including books, posters, and videos that feature people of different body types — not just the slim or athletic ones — helps kids understand that bodies come in all shapes and sizes,” he says.

He recommends:

Modeling balanced behavior at home: Focus on eating healthy “to feel strong” rather than “to stay slim.”

Media literacy: Teach children to question what they see in TV, ads, and social media. Help them understand that not everything shown is real or ideal.

Affirming non-appearance traits: Compliment children on their creativity, kindness, strength, or curiosity, not just their looks.

Encouraging open conversations: Avoiding the topic of body image can make it more taboo. Instead, create space for kids to talk about their feelings and the pressures they may face.

Parents: The First Role Models

One of the most effective strategies, according to Dr. Malhotra, is for parents to be mindful of their own body image talk.

“If you stand in front of the mirror criticizing your appearance, your child learns that bodies are to be judged,” he explains. “But if you focus on how your body helps you run, cook, or hug your child, that teaches gratitude and respect.”

The Durham study may have focused on how children see, but it’s what they hear and feel, especially from the adults around them, that gives those images meaning.

In a world of filtered faces and digitally enhanced bodies, helping a child grow up with a grounded, diverse sense of beauty may start with something as simple as changing the channel — or the conversation.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited