- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Why It’s Okay Not To Be A Perfect Parent- Lessons For New Parents

Why It’s Okay Not To Be A Perfect Parent- Lessons For New Parents

"I still remember that first time when my parents took me aside for what would turn out to be one of the most memorable conversations of my life. And so, I had only just finished my first gig as a drummer for a local band; although my parents weren't particularly keen on my choice of hobbies, they attended, cheered, and clapped. In my case, after the show, I was beaming with excitement, but my parents, without diminishing my enthusiasm, asked me what I had learned from the experience. That moment for me was a moment of crystallization, wherein I realized that my parents were not only supporting me but also helping me grow and introspect, eventually owning all the choices I made," narratives Raghav, now a sports psychologist in Bengaluru.

It has been very appealing in such a world with loads of parenting advice and parenting manuals to peruse often on what makes good parents perfect. It's about being perfect; it's not. It's about setting up a place where your child can flourish, where mistakes are an inherent part of the path you take, and love can be felt even through disagreements.

As we all explore our own experiences and those of others who had "good parents," there are some common threads that truly stand out — lessons that new parents can carry with them as they chart their own parenting journey.

Support Without Understanding

One important thing I learned from my parents is that you can never really understand the passion of your child in order to really support it. Not that my parents were not interested in skateboarding at all; however, they were willing enough to spend hours driving my brother to skateparks and continually buying new gear. They did not impose their dreams on us but allowed us to discover our own paths, even when that seemed out of step with theirs.

Similarly, though they did not reveal to me their love for drumming, they made quite an effort to enable me to pursue my dream. This freedom to explore taught me such an important life lesson : I am responsible for my own happiness. My parents were willing to support what they did not fully understand, giving me that courage to be passionate about things without fearing judgment.

New parents should remember that they don't have to micromanage everything their child might be interested in; it's all about giving them the space to find joy on their own terms and not to make them do something they are not deeply passionate about.

Power of Not Sheltering

The majority of parents have the instinct to protect their children from the pain or disappointment they will cause by being hurt or let down. My parents were entirely different. I was never sheltered nor protected from the harshest realities of life. My parents encouraged me to lose at sports, rejection, and to experience the diversity of society in all its implications-whether that was through having interactions with people from a different socioeconomic class or watching loved ones undergo difficult situations.

Instead of sheltering me from every knock and bump that came my way, they let me hit bottom and provided a pillow for me to fall on when the going got tough.

This should expose children to reality while at the same time providing support to help develop resilience. First-time parents will often find themselves wanting to protect their child from the upheavals of life, but, as it turns out, resilience is actually forged in the fire of trial. The children must be exposed to the capability to move through difficulties with support, not separation from the ease of life.

Leading by Example

My parents never asked me to do anything that they had not done themselves. If they taught us how to budget, then they themselves were under tight financial discipline. If they wanted us to treat people with kindness and respect, then they embodied those values in their dealings with others. They lived by the lessons that they would teach, so I found it easy to emulate them.

Indeed, one of the most powerful tools a parent has is leadership by example. Children are such observers, and they learn much more from what you do than from what you say. Want your children to live with integrity, discipline, and compassion? First, you must model those traits.

Breaking the Cycle of Trauma

The most important lesson I learned from my parents is breaking the cycle of trauma.

Both my parents are products of hard childhoods. While I was brought up by strangers much of his childhood, my father was abandoned. My mother suffered abuse from her own step-mother. They carried many scars, but they chose to give me and my siblings a life free from such pains.

Not perfect, to be sure-no parent ever is-but they made a conscious effort to build a loving, stable family environment. That this struggle means you are liberating yourself from your past and giving your children an opportunity for better life generally reminds us of something so important: no matter how one grows up, they can always choose to be different in parenting.

This is a good reminder for new parents- your past doesn't determine how you raise your children. You can create a nourishing home filled with love, even in the midst of serious struggles.

Respect and Fairness

One thing I was extremely thankful for while growing up was how my parents showed me and my siblings that they were fair. No one was a favorite, nor was anybody treated differently for some unknown agenda for others. Nothing was administered without some form of explanation, and decisions were always opened for discussion. It was never, "because I said so.".

This approach to parenting tended to build a relationship on mutual respect and trust. I never had the rebellion phase, not so much because I didn't want to be the rebel but I always felt heard. This is a very important lesson that new parents must know: respect breeds respect. By treating your child as a thinking human being who can engage in conversation, you help him grow into a responsible adult.

Parenting is a journey - well, my gosh; it's something that has been through loads of moments of doubt, learning, and growth. My parents aren't perfect, but they got a lot right: provided me with the space to focus on those things that interest me, allowed me to go through the ups and downs in life, modeled behavior for me to follow, and most importantly, they broke the cycle of trauma to give my siblings and me a better life.

So, you're not trying to be perfect; you're trying to love them, support them, and grow with them. Parenting is that process of providing a space where your children feel empowered to make their choices and supported in their pursuit, with values that you live each day. Parenting is not just protecting children from the world, but building resilience for life.

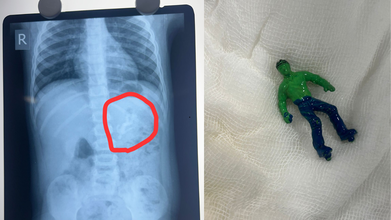

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy, Showed X-Ray, Doctors Remove It Via Endoscopy

Credits: X

Ahmedabad toddler, one-and-a-half-year-old boy swallowed a 'Hulk' toy, which is based on a popular comic superhero. The toy was stuck in his stomach when his parents took him to the Civil Hospital. According to reports by News18, the child is identified as Vansh who showed the signs of discomfort and began vomiting. This is what alarmed the parents.

As per the News18 report, his mother Bhavika was suspicious when she noticed that one of his toys was missing. The child was rushed to the hospital and an X-ray revealed that he had swallowed the entire plastic toy. The toy was not broken.

Hindustan Times reported that Dr Rakesh Joshi, Head of the Department of Pediatric Surgery removed the toy through upper GI endoscopy. "Had it been a little late, the toy could have moved further from the stomach and got stuck in the intestines. In that case, there would have been a risk of intestinal blockage and even rupture," the senior doctor said.

"There is a natural valve between the esophagus and the stomach. The biggest challenge was to take out a whole toy through this valve. When we tried to grab it with the endoscope, the toy kept slipping because of the air in the stomach. Pulling the toy by its hand or foot raised the possibility of it getting stuck in the valve and causing it permanent damage," he said.

The doctor noted that if the toy had further slipped down, it would have increased the risk of intestine rupturing.

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy: What Parents Must Keep In Their Mind

Under the Toys (Quality Control) Order, 2020 issued by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, toy safety in India was brought under mandatory BIS certification from September 1, 2020. The move aims to ensure safer toys for children while also supporting the government’s policy of curbing non-essential imports.

Industry sources estimate that more than 85 percent of toys sold in India are imported. Officials say the Toys Quality Control Order is a key step in preventing the entry of cheap and substandard toys into the domestic market, many of which fail to meet basic safety requirements.

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy: Standards for Electric and Non-Electric Toys

The quality control order clearly defines safety standards based on the type of toy. Non-electric toys such as dolls, rattles, puzzles, and board games must comply with IS 9873 (Part 1):2019. These toys do not rely on electricity for any of their functions.

Electric toys, which include at least one function powered by electricity, are required to meet the standards outlined under IS 15644:2006. Compliance with these standards is mandatory before such toys can be sold in the Indian market.

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy: Risks Linked to Untested Toys

Toys that are not tested by NABL-accredited toy testing laboratories can pose serious health risks to children. Sharp edges and poorly finished parts can cause cuts and injuries. PVC toys may contain phthalates, which are considered harmful chemicals.

Many low-quality toys have also been found to contain lead, a substance known to be particularly damaging to brain development in children. Soft toys with fur or hair can trigger allergies or become choking hazards. In some cases, small body parts can get stuck in gaps or holes, increasing the risk of injury.

Testing by NABL-accredited laboratories ensures that toys are safe, durable, and suitable for specific age groups. Parents are advised to check for IS marks on toys before purchasing, as this indicates compliance with Indian safety standards.

Ahmedabad Toddler Swallows Hulk Toy: What Parents Should Check Before Buying Toys

Experts recommend avoiding toys with small detachable parts for toddlers and young children, as they are more likely to put objects in their mouths. Toys should always match the child’s age, skill level, and interests.

Parents are also urged to look for IS marks, which confirm that the toy has been tested and certified. Loud toys should be avoided, as prolonged exposure to sounds above 85 decibels can harm a child’s hearing.

Electric toys with heating elements should be used with caution or avoided altogether due to burn risks. Finally, toys with sharp edges or shooting components should be carefully examined to prevent cuts and injuries.

Tech And Devices Have 'Horrific' Impact On Kids, Says Study

Credits: iStock

Doctors across the UK are raising the alarm over what they describe as mounting evidence of serious health harms linked to excessive screen time and unrestricted access to digital content among children and young people.

The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (AoMRC), which represents 23 medical royal colleges and faculties, says frontline clinicians are witnessing deeply concerning patterns across the NHS. According to the academy, doctors working in primary care, hospitals and community settings have shared firsthand accounts of what they describe as “horrific cases” affecting both physical and mental health.

Evidence From the Frontline

The academy has now launched a formal evidence-gathering exercise to better understand the harms clinicians are repeatedly encountering and whether these can be attributed to technology use and digital devices.

Its aim is twofold. First, to shine a light on risks that often go unnoticed, including prolonged screen time and exposure to harmful online content. Second, to develop guidance for healthcare professionals on how to identify, address and manage these issues in clinical practice.

In a statement, the AoMRC said it already has evidence pointing to significant impacts on children’s wellbeing, ranging from physical concerns to mental health challenges linked to both excessive device use and harmful online material. The work is expected to be completed within three months.

A Public Health Emergency?

Dr Jeanette Dickson, chair of the academy, said the scale of the problem is becoming impossible to ignore. Speaking to The Sunday Times, she warned that clinicians may be witnessing the early stages of a public health emergency.

“Everywhere we look, we see children and adults glued to their screens,” she said. “I really worry for children, some of whom are self-evidently imprisoned in a digital bubble.”

Copies of the academy’s letter outlining these concerns have been sent to Health Secretary Wes Streeting and Science and Technology Secretary Liz Kendall, as well as Lucy Chappell, chief executive of the National Institute for Health Research, and the government’s chief medical adviser, Sir Chris Whitty.

Government Action and Global Trends

The warnings come as the UK government prepares to consult on possible restrictions on social media use for under-16s. Options under consideration range from a complete ban to more targeted measures such as time limits and tighter controls on algorithms.

Recent government research has already linked screen time to poorer speech development in children under five. Internationally, the debate is gaining pace. Australia introduced a ban on under-16s holding social media accounts in December, while countries including France, Denmark, Norway and Malaysia are weighing similar steps.

Why Some Groups Oppose a Blanket Ban

Not everyone agrees that an outright ban is the answer. A joint statement signed by 43 child protection charities and online safety groups, including the NSPCC and the Molly Rose Foundation, warns that blanket bans could backfire.

Andy Burrows, chief executive of the Molly Rose Foundation, said parents and policymakers are being offered a false choice. “It’s being framed as either a total ban or the current appalling status quo,” he said. “Those aren’t the only options.”

Chris Sherwood, chief executive of the NSPCC, echoed the concern, pointing out that for many children, the internet provides vital support. “A blanket ban would take those spaces away overnight,” he said, “and risks pushing teenagers into darker, unregulated corners of the internet.”

Both organizations argue that the focus should shift to holding tech companies accountable for harmful design choices, unsafe algorithms and failures to protect young users.

Cold Weather And Low Fertility; Is There A Link? Explains Doctor

Credits: Canva

As winter sets in, conversations around health often shift to immunity, joint pain, and seasonal illnesses. But can colder weather also influence fertility? According to experts, cold weather does not directly cause infertility, but it can quietly affect hormones and reproductive health through lifestyle and biological changes.

Dr Geeta Jain, HOD of Obstetrics, Gynecology and IVF, and Co-founder of Maccure Hospital and Aastha Hospital, explains that fertility is rarely impacted by temperature alone. “Cold weather does not directly cause infertility, but it can have an indirect impact on fertility and hormonal balance,” she says.

How Seasonal Changes Affect Hormones

One of the most significant winter-related changes is reduced exposure to sunlight. Shorter days and limited sun can influence the body’s hormonal rhythm, particularly melatonin and vitamin D levels. These hormones are closely linked to reproductive hormones such as estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone.

“Lower sunlight levels can affect the secretion of melatonin and vitamin D, both of which play an important role in reproductive health,” Dr Jain explains. Vitamin D deficiency, which is more common during winter months, has been associated with irregular menstrual cycles, ovulatory issues, and conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). All of these factors can make conception more challenging.

Menstrual Changes During Winter

Some women notice changes in their menstrual cycles during colder months, including delayed periods, increased cramps, or irregular ovulation. However, temperature is not the main culprit.

“These changes are often linked to lifestyle factors rather than cold weather itself,” says Dr Jain. Reduced physical activity, weight gain, changes in diet, and increased consumption of high-calorie comfort foods during winter can disrupt insulin sensitivity and hormonal balance. Over time, this may indirectly affect ovulation and fertility.

Stress, Mood, and Fertility

Mental health also plays a critical role in reproductive health, especially during winter. Shorter days and less outdoor activity can contribute to seasonal mood changes, anxiety, or even depression. These emotional shifts can elevate cortisol, the body’s stress hormone.

“Elevated cortisol can interfere with the normal functioning of reproductive hormones,” Dr Jain notes. If stress becomes chronic, it may affect ovulation and fertility over time, even in otherwise healthy individuals.

Does Cold Weather Permanently Affect Fertility?

The good news is that winter-related hormonal changes are usually temporary. “Cold weather does not permanently harm fertility,” Dr Jain reassures. Most seasonal shifts can be reversed by adopting healthy habits.

Maintaining a balanced, nutrient-rich diet, staying physically active indoors or outdoors, managing stress, getting adequate sleep, and ensuring sufficient vitamin D intake can help support hormonal balance throughout the colder months.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited